Can't Dance, Won't Dance? Better Learn How to Dance

Baruti Kafele, a school principal turned inspirational speaker with whom I’ve worked several times, used to love quoting an Ashanti proverb to throw cold water on teachers’ complaints about all the things allegedly standing between them and good instruction: “He who cannot dance will say the drum is bad.” He’s a no-excuses kind of guy, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t acknowledge challenges and difficulties. There’s a difference between a reason and an excuse, and God knows there are plenty of reasons why teaching is hard—especially today. But do we accept them as excuses for why we can’t get to Good?

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

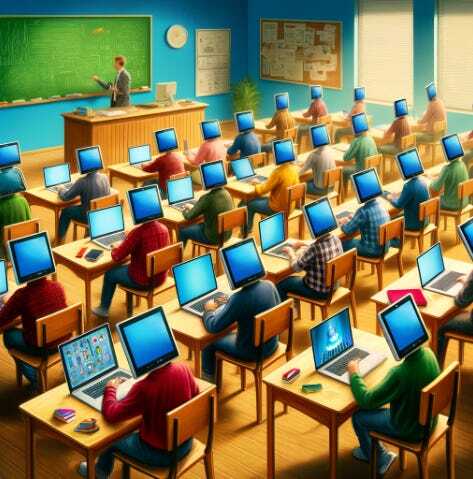

When it comes to complaints about the over-use of technology in the classroom, I don’t want to take the Cher approach…

But I do think we need to find ways not to blame the drum, because…that drum isn’t going anywhere.

There was an opinion piece on classroom technology in the New York Times last week that got a lot of attention around my workplace, which is not surprising, given that I work in ed tech. You don’t have to go any further than the title to know what its take is going to be: “Get Tech Out of the Classroom Before It’s Too Late.” If the Times style guide allowed exclamation points in headlines, there would have been two or three in this one.

There are real and serious issues explored in this piece—elementary and middle school students getting access to violent YouTube videos while in school; kids reading “almost exclusively on iPads because their school districts had phased out hard-copy books and writing materials;” teachers finding it difficult to hold the attention of their students when technology is at their fingertips. These are real concerns. I just don’t think “getting tech out our classrooms” is a realistic solution. As with so many things, the extreme pendulum swings are not where the best solutions lie. There is a happy medium to be found, and it’s not in yelling at the drum; it’s in learning how to dance better. It’s hard work, but it’s on us—all of us—to do that work.

I heard from many parents who said that even when they asked district leaders how much time kids were spending on their screens, they couldn’t get straight answers; no one seemed to know, and no one seemed to be keeping track.

That quote is part of the problem—maybe the root cause of the problem. It’s the responsibility of school leaders to know what they’re bringing into a building and how it’s being used, whether that’s a textbook, a computer, the mystery meat being served for lunch, or a piece of athletic equipment. I know, I know. “There’s so much, it’s so complicated, how can I possibly keep track?” I get it. But too bad. You have to keep track; you’re the gatekeeper. You’re the guard at the door, and there are children inside. Do the due diligence.

Are some tech companies being irresponsible and greedy? Are they overpromising and underdelivering? Are they not putting adequate guardrails around their products? Are they designing their products deliberately to be as engaging and “sticky” as possible? Yes, my sweet, summer child: some companies in the great marketplace of life are bad and irresponsible actors. Welcome to Capitalism.

Some; not all. Some companies providing tech products and services to schools take their jobs and their responsibilities very seriously, and try hard to be good actors and honest brokers. Ask around; find out who you should trust…and how far you should trust them. Caveat emptor.

But the drum itself doesn’t make the dance. Bringing the right product into the building is part of the battle, but how the product is used matters, too. When, where, how often, and how.

"Letting kids do whatever they want on laptops or phones all day," is no one's idea of good teaching, so why is it happening? I think it happens because there’s a gap between good intentions and actual implementation. As T.S. Eliot says, “between the idea and the reality falls the shadow.”

If there is irresponsible product design going on in some places, there is also bad implementation happening out in the world, and some thoughtless teaching, too. Some of it may be the responsibility of the vendor, as I said above, but schools need to own their part, too. I’ve been in plenty of districts that treated professional development as a checklist, and didn’t particularly care (or check to find out) whether teachers were learning anything or changing their practice.

There’s a long chain of custody from the people who make a product (even a textbook) to the people who ultimately use it. Do superintendents or curriculum directors know why they’ve purchased a piece of education technology? Have they connected that “why” to some clearly defined and achievable goals? Have they shared the “why” and the goals with their teachers? Have they put systems in place to support teachers if they’re expecting some change in practice? Have they put systems in place to track progress towards and measure achievement of those goals? If the answer to any of those questions is “no,” things are going to fall apart somewhere between signing the check for the New Cool Thing and how that thing is used in a particular classroom with a particular child.

There are better and worse ways to make use of technology, from laptops to phones to generative AI (the latter of which I wrote about here and here). Being deliberate about its use, and when to pull back from it, is not only good classroom practice; it’s good modeling for the large and rich life we want our students to lead outside of school and as adults. When schools create a technology plan, as most of them do, these days, it should involve more than the purchasing of things and the wiring of infrastructure to support those things; it should also include a holistic vision of how those things should be used, when they should not be used, and to what ends.

There’s no reason not to be honest and up-front about these issues with students. They’re not simply passive victims or recipients of technology (any more than they should be passive victims or recipients of instruction); they are active users of it outside of school, and will be for the rest of their lives. We need their understanding and their participation, if we don’t want them surreptitiously going onto their phones in the middle of a lesson.

I think part of "media literacy" in schools should involve helping children become more self-aware and metacognitive about the effects of tech on their brains: how dependent they can become on the constant visual and aural stimulation; how different it feels to read and write offline; and even the value of "going analog" from time to time, as my wife used to call it with our kids.

As adults in loco parentis, school folk need to make good and wise decisions about the use of technology for the children in their care. But as with everything else in school, we also need to help them learn, gradually, how to manage their own minds and choices and lives. That’s the whole goal of an education, after all.

Scenes from a Broken Hand

- Andrew Ordover's profile

- 44 followers