Conkling, Grant, and the “famous apple tree” of Appomattox

The back story of Roscoe Conkling’s nomination speech for Ulysses S. Grant at the 1880 Republican convention in Chicago.

Roscoe Conkling, the imperious boss of the New York Republican Party, arrived in Chicago in the spring of 1880 to lead the effort to make Union war hero and former president Ulysses S. Grant the party’s nominee.

Tall, handsome, and a flamboyant dresser with a distinctive Hyperion curl falling across his brow, Conkling became an object of public fascination as the Republican convention began on June 2 at the Interstate Industrial Exposition Center on Michigan Avenue. “He cannot pass through a hotel corridor without drawing a number of people in his wake,” the New York Tribune reported. When he sat down to breakfast, crowds gawked until they were turned away by the head waiter. “Mr. Conkling seats himself,” the Tribune continued, “and his striking face crowned with hair something between auburn and white, with a complexion that may be called vivid whiteness, and a short-pointed auburn beard, becomes henceforth the great Grant landmark of the convention.”

Grant had been nominated by acclamation in 1868 and 1872, but this time he faced competition as he sought an unprecedented third term in the White House. His leading opponent — and Conkling’s arch-rival — was James G. Blaine, who along with Conkling had been defeated for the party’s nomination four years earlier when Republicans meeting in Cincinnati selected Rutherford B. Hayes as their candidate.

Despite his celebrity status, the “Great Grant landmark” antagonized the convention shortly after it opened when he demanded the expulsion of three West Virginia delegates who opposed his resolution committing delegates to support the eventual nominee. The ham-handed move enabled James A. Garfield to win admirers by defending the West Virginia delegates and signaled that the autocratic manner in which Conkling ran the Republican Party in New York would not play well on the convention floor.

But Conkling still commanded the attention — if not the affection — of the delegates. And when it came time to nominate Grant, Conkling displayed the theatrical instinct that had served him so well on the campaign trail in New York and on Capitol Hill.

“As Conkling marched to the front, erect and confident, his form towering head and shoulders above most other men around him, his splendid presence seemed to confirm reports of his power,” Iowa historian and journalist Johnson Brigham would recall years later. “A flatteringly long ovation awaited him.”

Appomattox Court House, 1865. Library of Congress.

Appomattox Court House, 1865. Library of Congress.He climbed atop a table used by reporters. “It was the most conspicuous elevation in the hall,” according to the New York Sun. Conkling “bowed to all points of the compass, and saluted a friend in the gallery.”

He began by making an unorthodox rhetorical decision. In his book on Gilded Age politics, journalist Joseph Bucklin Bishop noted that the original text of the speech, distributed to newspapers in advance and widely reprinted, begins with the simple declaration: “When asked whence comes our candidate, we say from Appomattox.”

Perhaps encouraged by the enthusiastic welcome he received, Conkling “took the bold hazard of springing on his hearers a climax at the very outset,” Brigham recalled. Instead of an unadorned reference to the site of the Confederate surrender that ended the Civil War, Conkling began with a short piece of verse: “When asked from state he hails from, our sole reply will be/He hails from Appomattox, and its famous apple tree.”

The couplet was familiar to Republicans. It came from a campaign song penned for Grant’s 1868 presidential campaign by Charles G. Halpine, better known by the non de plume Miles O’Reilly.

Like a delayed fuse, Conkling’s rhetorical gambit did not trigger an immediate reaction, but it eventually rocked the hall. “At first the few applauded, but when the Grant delegates grasped the significance of the lines, they rose and made one of the most genuinely spontaneous demonstrations of the convention,” Brigham recalled.

Much of Conkling’s speech was an eloquent paean to Grant. “Never defeated, in peace or in war, his name is the most illustrious borne by living man,” Conkling declared. “His services attest to his greatness, and the country — nay, the world — knows them by heart.”

As president, Grant “cleared the way” for a return to the gold standard with his veto of the inflation bill in 1874, Conkling claimed. The veto divided Republicans at the time, but by 1880 it looked farsighted (although controversy over monetary policy would return with a vengeance a decade later). Because of Grant, Conkling told the convention, “every paper dollar is at last as good as gold.”

“Life, liberty, and property will find a safeguard with him,” Conkling continued. Grant’s return to the White House would mean Black Southerners “would no longer be driven in terror from the homes of their childhood and the graves of their murdered dead.” When Grant spurned a chance to meet with Dennis Kearney, the Sinophobic leader of the Workingman’s Party in San Francisco, “he meant that communism, lawlessness, and disorder, although it might stalk high-headed and dictate law to a whole city, would always find a foe in him.”

With many Republicans opposed to Grant’s nomination on the grounds that it would break the two-term tradition, Conkling addressed the issue directly. Barring a successful president from returning to office after two terms would “dumbfounder Solomon, because Solomon thought there was nothing new under the sun.” It makes no sense to deny a third term to a successful president who has served eight years in office, Conkling argued. “Show me a better name,” Conkling dared Grant’s critics. “Name one, and I am answered. But do not point as a disqualification to the very experience which makes this man fit beyond all others.”

Conkling’s eloquent affirmative case for Grant helped make the speech one of the most memorable political orations of the Gilded Age. “Next to the speech of [Robert] Ingersoll, who nominated Blaine in 1876, Conkling’s appeal for the nomination of Grant will stand as the ablest of all the many able deliverances in the history of American politics,” journalist A.K. McClure declared. If he had stopped there, Conkling might have united the party, McClure believed. But the New Yorker, whose enmity toward Blaine dated back to an exchange of insults on the House floor in 1866, laced his speech with barbs directed at the popular senator from Maine.

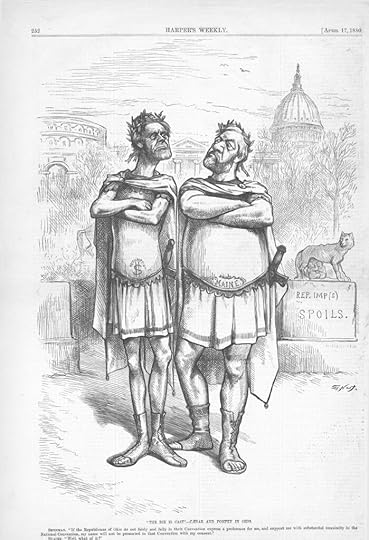

John Sherman of Ohio (left), one of the contenders for the 1880 Republican presidential nomination, and James G. Blaine of Maine regard each other warily in this Thomas Nast cartoon from Harper’s Weekly.

John Sherman of Ohio (left), one of the contenders for the 1880 Republican presidential nomination, and James G. Blaine of Maine regard each other warily in this Thomas Nast cartoon from Harper’s Weekly.Grant’s nomination would enable Republicans to go on the attack against Democrats. “We shall have to explain nothing away,” Conkling said in a veiled shot at Blaine that ignored the corruption that marred Grant’s two terms in office. More directly, Conkling contrasted what he claimed was the spontaneous outpouring of public support for Grant with the scheming of his opponents.

“Without patronage, without emissaries, without committees, without bureaux, without telegraph wires running from his house or the seats of influence to this convention, Grant’s name is on his country’s lips,” Conkling said. The reference to “telegraph wires” tweaked Blaine, who installed a telegraph at his home to follow developments on the convention floor. The claim that support for Grant came unprompted from voters also overlooked the fact — well-known in the convention hall — that Conkling was at the head of a trio of Republican bosses known as the “Triumvirate” backing the former president.

Conkling’s digs at Blaine weakened its impact of his speech, McClure believed. “Unlike the Ingersoll speech nominating Blaine in 1876, the speech of Conkling, able, eloquent, and grand as it was, left Grant weaker, instead of stronger.” The Grant and Blaine forces deadlocked through 35 ballots until Garfield emerged to claim the nomination on the 36th ballot.

As for the verse Conkling opened his speech with, no less an authority than Grant dismissed it as a pleasant but inaccurate legend. “Wars produce many stories of fiction, some of which are told until they are believed to be true,” he wrote in his memoirs. The tale that he accepted Lee’s surrender under an apple tree at Appomattox “would be very good if it was only true.”

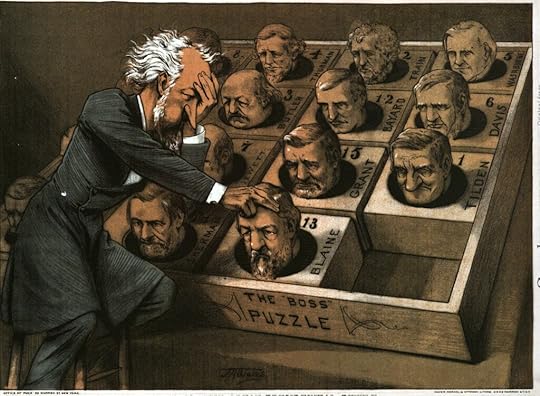

Puck’s rendering of the “presidential puzzle box” of 1880 shows Conkling trying to push down James G. Blaine.

Puck’s rendering of the “presidential puzzle box” of 1880 shows Conkling trying to push down James G. Blaine.__________________

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age is coming this fall from Edinborough Press. Also published by Edinborugh and available at Amazon.com:

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver