Voynich Reconsidered: 2 for 1

In the course of my research for Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, 2024), I developed several variants of Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration of the Voynich manuscript. The purpose of these alternative transliterations was to test the hypothesis that the glyphs in v101 might be interpreted in different ways.

For example, the v101 glyphs {2}, {3}, {5} and several others look as if they might be the same glyph; likewise, the glyphs {6}, {7}, {8} and {&} seem to have only minor differences. Conversely, v101 glyphs such as {m}, {n} and {z} look like they should be disaggregated into strings of smaller glyphs. And the glyph string {4o}, which is conventionally treated as two glyphs, is surely a single glyph, since {4} rarely appears on its own.

Using each of these alternative transliterations as a source document, and applying frequency analysis, I mapped the Voynich glyphs to letters in selected medieval European languages. In some cases, these mappings yielded text strings that were real words in the selected languages.

Corpora of reference

The selection of those languages was a matter of trial and error, as well as of availability of corpora of reference. I was guided by the distance-decay hypothesis, which favored languages spoken and written in medieval Italy (such as Tuscan-Italian and Latin), and in nearby countries. Also, the correlations of glyph frequencies and letter frequencies gave some guidance as to which transliterations, and which precursor languages, were more encouraging than others.

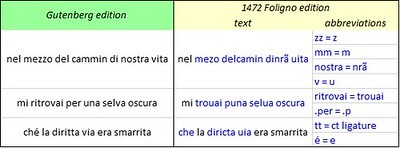

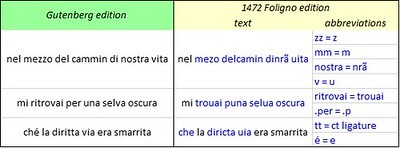

I suspected that the precursor documents (especially in Italian or Latin) might have been in abbreviated scripts, but machine-readable corpora of abbreviated medieval texts appeared to be non-existent. I created an abbreviated Latin version of Dante's De Monarchia, drawing upon Cappelli's Lexicon Abbreviaturarum; and an abbreviated Italian version of La Divina Commedia, based on the observable abbreviations on the first page of the first printed edition, published in Foligno in 1472. In that edition, all modern accents disappear; the modern "v" becomes "u"; and there are relatively few doubled letters.

Examples of abbreviations and spelling conventions in the 1472 Foligno edition of La Divina Commedia. Author's analysis.

Each of my alternative transliterations has a different set of glyph frequencies from that of the original v101. For the most common Voynich glyphs, there are relatively good matches (in terms of frequencies) for the most common letters in European languages. However, when we get down to the less common glyphs, there is much more uncertainty in the matching of frequencies. Considerations such as this prompted me to wonder whether certain glyphs should be redefined.

{2} and its variants

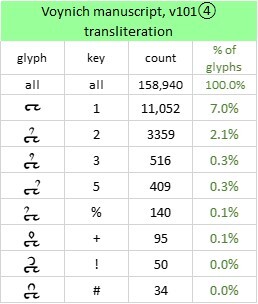

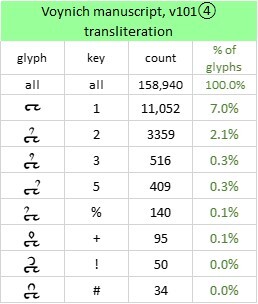

The v101 glyph {1} is the fifth most common in the Voynich manuscript, with a frequency of 7.0 percent. What I find intriguing about {1} is that it is the leader of a family of eight glyphs, in which each of the other seven glyphs consists of a {1} with what looks like a superscript or diacritic. These superscripts might be some form of abbreviation – perhaps they represent omitted vowels or consonants – or else some form of punctuation. If so, we could redefine {2} and each of its variants as {1} plus superscript (for the moment, treating all the superscripts as the same).

The {1} family of glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v101 transliteration. Author’s analysis.

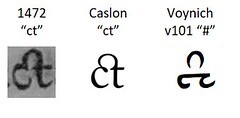

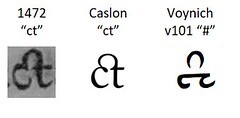

(In passing we may note that the v101 glyph {#} bears a resemblance to the Foligno ligature "ct", which the English printer William Caslon (1692-1766) later copied in his famous Caslon font. It is of course tempting to equate {#} with the "ct" ligature, but the frequencies do not come close to matching; the Foligno “ct” is quite common, but the glyph {#} is rare.)

The Foligno "ct" ligature, Caslon's "ct", and the v101 glyph {#}. Images: public domain.

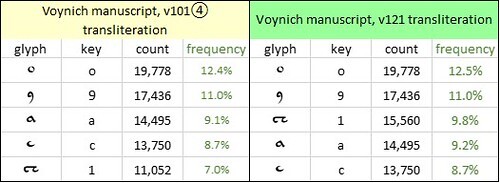

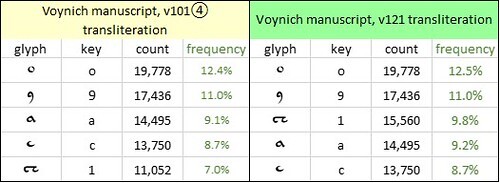

To this end, I developed what I called the v121 transliteration, in which {2} and its variants were thus redefined. This increased the frequency of the glyph {1} from 7.0 percent to 9.8 percent, making it the third most common glyph. (Therefore, if the Voynich glyphs had been mapped one-to-one from letters in natural languages, {1} would probably represent a vowel.) Among the most common glyphs, the frequencies changed as follows:

The five most frequent glyphs in the v101④ and v121 transliterations. Author's analysis.

Testing v121

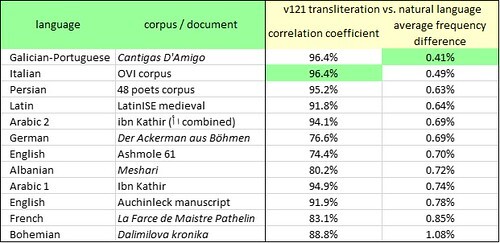

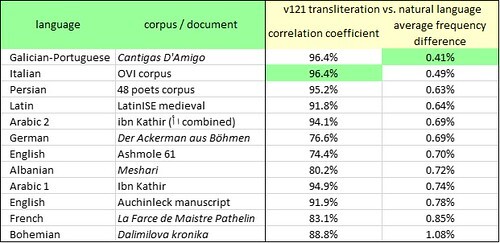

In order to test the v121 transliteration, my first step was to examine which natural languages had the best statistical fit with this transliteration. I compared glyph frequencies with letter frequencies, using two alternative metrics (as outlined in other posts on this platform): the correlation coefficient, and the average frequency difference. The results are summarised below.

A comparison of the glyph frequencies in the Voynich manuscript, v121 transliteration, and the letter frequencies in selected medieval languages. Author’s analysis.

Here we see that medieval Galician-Portuguese and Italian are the best-fitting languages (depending on which metric we use).

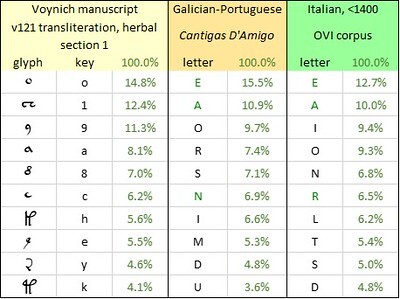

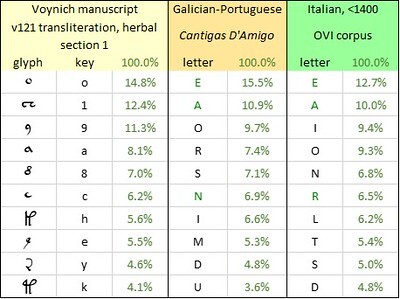

The next step was to line up the glyph frequencies in v121 with the letter frequencies in Galician-Portuguese and Italian, creating a provisional glyph-to-letter mapping. For this purpose, for some assurance of mapping from a single Voynich “language”, I used the glyph frequencies in the “herbal” section. A frequency comparison for the top ten glyphs and letters is shown below.

The top ten glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v121 transliteration, “herbal” section (as defined by Zandbergen); and the top ten letters in medieval Galician-Portuguese and Italian. Author’s analysis.

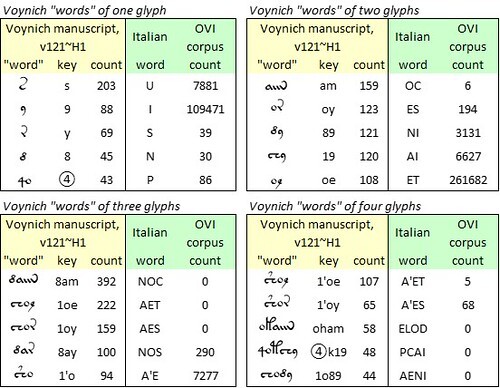

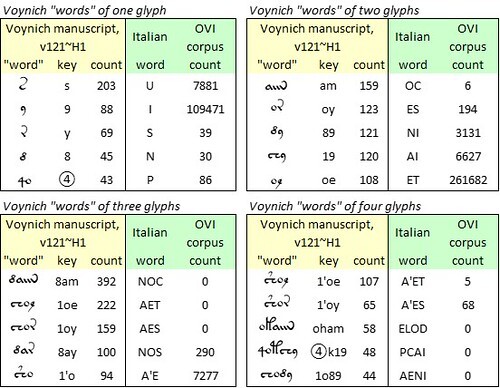

The next step was to map the most frequent Voynich “words” into Galician-Portuguese and Italian, and see whether the results made any sense. Here, as in other mappings that I have tested, I selected the five most frequent “words” of one, two, three and four glyphs. A summary of the results for Italian is below.

Voynich manuscript, v121 transliteration, “herbal” section: the most common “words” of one to four glyphs; and raw mappings to medieval Italian. Author’s analysis.

Here, I detected a phenomenon that was evident in other mappings that I tried, from Voynich transliterations to selected medieval languages. For very short Voynich “words”, of one of two glyphs, the mapping yielded real words in Italian. But this could be pure chance or coincidence. For “words” of three or four glyphs, the mapping tended to break down.

At this point, it seemed that D’Imperio’s “five states” and Zattera’s “slot alphabet” might come to the rescue. As I have observed in several other articles on this platform, D’Imperio’s and Zattera’s findings are persuasive evidence that the Voynich scribes re-ordered the glyphs in some way. Specifically, the order of the glyphs within “words” is so inflexible that we are compelled to conjecture that the glyphs are not in their original order.

If this was the case, then we have to imagine what sequences of letters in the precursor languages could have yielded the “words” that we see in the Voynich manuscript. That is: we have to look for anagrams. This is a process to be attempted with great caution, since anagrams can lead us into a world of subjectivity. A word of just four letters has twenty-four anagrams; a word of five letters has 120. If we accept any anagram of a five-letter word, we permit ourselves 120 degrees of freedom.

However, an anagram has to make sense. It has to be a real word, and a common one. We have to find it in a corpus of the precursor language, and it has to occur with a reasonable frequency. Ultimately, if we generate a string of anagrams, the sequence has to make sense.

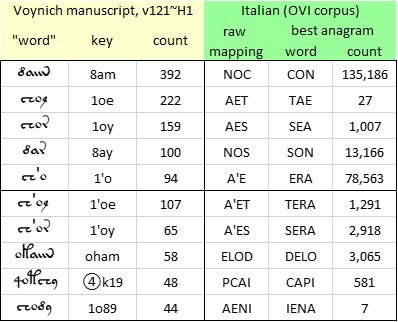

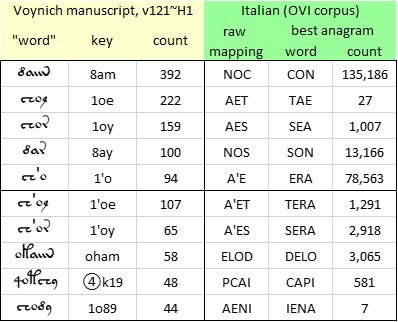

Here, I turned to the OVI corpus of medieval Italian. OVI stands for Opera del Vocabolario Italiano. It is the largest database of the Italian language as used before 1400. Currently, the corpus contains 3,443 texts with 30,245,108 words. In cases where my raw mappings of Voynich “words” did not yield real Italian words, I looked for plausible and pronounceable anagrams and searched for occurrences of these anagrams in the OVI corpus. A summary of the results is below.

Voynich manuscript, v121 transliteration, “herbal” section: trial mappings of selected “words” to medieval Italian. Author’s analysis.

To my mind, what was encouraging about this process is that it lent support to the hypothesis that the Voynich scribes re-ordered the glyphs in some or all of the Voynich “words”. To take just one example: if a scribe came across the ubiquitous Italian word “con” (in English: “with”); and if the mapping that he used was something like my v121 transliteration; then he would map the Italian word to the Voynich “word” {ma8}. But on the wall or desk of the workplace, the producer had affixed a rule that this was not a permitted order of glyphs within a “word”; the order had to be {8am}. Accordingly, this is what the scribe wrote down.

In these mappings, I can see some evidence that the re-ordering rule might have been even more basic. The rule might have been simply to reverse the order of the glyphs in every “word”. This looks like what the scribe did to arrive at {8am}; also {8ay}; possibly also {2oe} and {2oy}.

This is by no means the end of the story. My v121 transliteration is a simple variant of v101; it is not necessarily the right one. But it lends weight to the hypothesis that {2} and its sister glyphs are variants of {1}. To take this hypothesis further, I will need to map more “words”, and in due course, lines of Voynich text; and the mappings will have to make sense. On this, more later.

For example, the v101 glyphs {2}, {3}, {5} and several others look as if they might be the same glyph; likewise, the glyphs {6}, {7}, {8} and {&} seem to have only minor differences. Conversely, v101 glyphs such as {m}, {n} and {z} look like they should be disaggregated into strings of smaller glyphs. And the glyph string {4o}, which is conventionally treated as two glyphs, is surely a single glyph, since {4} rarely appears on its own.

Using each of these alternative transliterations as a source document, and applying frequency analysis, I mapped the Voynich glyphs to letters in selected medieval European languages. In some cases, these mappings yielded text strings that were real words in the selected languages.

Corpora of reference

The selection of those languages was a matter of trial and error, as well as of availability of corpora of reference. I was guided by the distance-decay hypothesis, which favored languages spoken and written in medieval Italy (such as Tuscan-Italian and Latin), and in nearby countries. Also, the correlations of glyph frequencies and letter frequencies gave some guidance as to which transliterations, and which precursor languages, were more encouraging than others.

I suspected that the precursor documents (especially in Italian or Latin) might have been in abbreviated scripts, but machine-readable corpora of abbreviated medieval texts appeared to be non-existent. I created an abbreviated Latin version of Dante's De Monarchia, drawing upon Cappelli's Lexicon Abbreviaturarum; and an abbreviated Italian version of La Divina Commedia, based on the observable abbreviations on the first page of the first printed edition, published in Foligno in 1472. In that edition, all modern accents disappear; the modern "v" becomes "u"; and there are relatively few doubled letters.

Examples of abbreviations and spelling conventions in the 1472 Foligno edition of La Divina Commedia. Author's analysis.

Each of my alternative transliterations has a different set of glyph frequencies from that of the original v101. For the most common Voynich glyphs, there are relatively good matches (in terms of frequencies) for the most common letters in European languages. However, when we get down to the less common glyphs, there is much more uncertainty in the matching of frequencies. Considerations such as this prompted me to wonder whether certain glyphs should be redefined.

{2} and its variants

The v101 glyph {1} is the fifth most common in the Voynich manuscript, with a frequency of 7.0 percent. What I find intriguing about {1} is that it is the leader of a family of eight glyphs, in which each of the other seven glyphs consists of a {1} with what looks like a superscript or diacritic. These superscripts might be some form of abbreviation – perhaps they represent omitted vowels or consonants – or else some form of punctuation. If so, we could redefine {2} and each of its variants as {1} plus superscript (for the moment, treating all the superscripts as the same).

The {1} family of glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v101 transliteration. Author’s analysis.

(In passing we may note that the v101 glyph {#} bears a resemblance to the Foligno ligature "ct", which the English printer William Caslon (1692-1766) later copied in his famous Caslon font. It is of course tempting to equate {#} with the "ct" ligature, but the frequencies do not come close to matching; the Foligno “ct” is quite common, but the glyph {#} is rare.)

The Foligno "ct" ligature, Caslon's "ct", and the v101 glyph {#}. Images: public domain.

To this end, I developed what I called the v121 transliteration, in which {2} and its variants were thus redefined. This increased the frequency of the glyph {1} from 7.0 percent to 9.8 percent, making it the third most common glyph. (Therefore, if the Voynich glyphs had been mapped one-to-one from letters in natural languages, {1} would probably represent a vowel.) Among the most common glyphs, the frequencies changed as follows:

The five most frequent glyphs in the v101④ and v121 transliterations. Author's analysis.

Testing v121

In order to test the v121 transliteration, my first step was to examine which natural languages had the best statistical fit with this transliteration. I compared glyph frequencies with letter frequencies, using two alternative metrics (as outlined in other posts on this platform): the correlation coefficient, and the average frequency difference. The results are summarised below.

A comparison of the glyph frequencies in the Voynich manuscript, v121 transliteration, and the letter frequencies in selected medieval languages. Author’s analysis.

Here we see that medieval Galician-Portuguese and Italian are the best-fitting languages (depending on which metric we use).

The next step was to line up the glyph frequencies in v121 with the letter frequencies in Galician-Portuguese and Italian, creating a provisional glyph-to-letter mapping. For this purpose, for some assurance of mapping from a single Voynich “language”, I used the glyph frequencies in the “herbal” section. A frequency comparison for the top ten glyphs and letters is shown below.

The top ten glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v121 transliteration, “herbal” section (as defined by Zandbergen); and the top ten letters in medieval Galician-Portuguese and Italian. Author’s analysis.

The next step was to map the most frequent Voynich “words” into Galician-Portuguese and Italian, and see whether the results made any sense. Here, as in other mappings that I have tested, I selected the five most frequent “words” of one, two, three and four glyphs. A summary of the results for Italian is below.

Voynich manuscript, v121 transliteration, “herbal” section: the most common “words” of one to four glyphs; and raw mappings to medieval Italian. Author’s analysis.

Here, I detected a phenomenon that was evident in other mappings that I tried, from Voynich transliterations to selected medieval languages. For very short Voynich “words”, of one of two glyphs, the mapping yielded real words in Italian. But this could be pure chance or coincidence. For “words” of three or four glyphs, the mapping tended to break down.

At this point, it seemed that D’Imperio’s “five states” and Zattera’s “slot alphabet” might come to the rescue. As I have observed in several other articles on this platform, D’Imperio’s and Zattera’s findings are persuasive evidence that the Voynich scribes re-ordered the glyphs in some way. Specifically, the order of the glyphs within “words” is so inflexible that we are compelled to conjecture that the glyphs are not in their original order.

If this was the case, then we have to imagine what sequences of letters in the precursor languages could have yielded the “words” that we see in the Voynich manuscript. That is: we have to look for anagrams. This is a process to be attempted with great caution, since anagrams can lead us into a world of subjectivity. A word of just four letters has twenty-four anagrams; a word of five letters has 120. If we accept any anagram of a five-letter word, we permit ourselves 120 degrees of freedom.

However, an anagram has to make sense. It has to be a real word, and a common one. We have to find it in a corpus of the precursor language, and it has to occur with a reasonable frequency. Ultimately, if we generate a string of anagrams, the sequence has to make sense.

Here, I turned to the OVI corpus of medieval Italian. OVI stands for Opera del Vocabolario Italiano. It is the largest database of the Italian language as used before 1400. Currently, the corpus contains 3,443 texts with 30,245,108 words. In cases where my raw mappings of Voynich “words” did not yield real Italian words, I looked for plausible and pronounceable anagrams and searched for occurrences of these anagrams in the OVI corpus. A summary of the results is below.

Voynich manuscript, v121 transliteration, “herbal” section: trial mappings of selected “words” to medieval Italian. Author’s analysis.

To my mind, what was encouraging about this process is that it lent support to the hypothesis that the Voynich scribes re-ordered the glyphs in some or all of the Voynich “words”. To take just one example: if a scribe came across the ubiquitous Italian word “con” (in English: “with”); and if the mapping that he used was something like my v121 transliteration; then he would map the Italian word to the Voynich “word” {ma8}. But on the wall or desk of the workplace, the producer had affixed a rule that this was not a permitted order of glyphs within a “word”; the order had to be {8am}. Accordingly, this is what the scribe wrote down.

In these mappings, I can see some evidence that the re-ordering rule might have been even more basic. The rule might have been simply to reverse the order of the glyphs in every “word”. This looks like what the scribe did to arrive at {8am}; also {8ay}; possibly also {2oe} and {2oy}.

This is by no means the end of the story. My v121 transliteration is a simple variant of v101; it is not necessarily the right one. But it lends weight to the hypothesis that {2} and its sister glyphs are variants of {1}. To take this hypothesis further, I will need to map more “words”, and in due course, lines of Voynich text; and the mappings will have to make sense. On this, more later.

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers