Voynich Reconsidered: the "truncation effect"

In the course of my research for Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Publishing, 2024), I made a series of statistical tests on the Voynich manuscript, based on the incidence of hapax legomena: that is, words that occur only once.

As Alexander Boxer demonstrated in his presentation to the Voynich 2022 conference, the prevalence of hapax legomena can be an indicator of the presence or absence of semantic meaning. Specifically, for a document of a given length, a lower incidence of hapax legomena is indicative of meaningful content. A higher incidence is a "fingerprint" of gibberish.

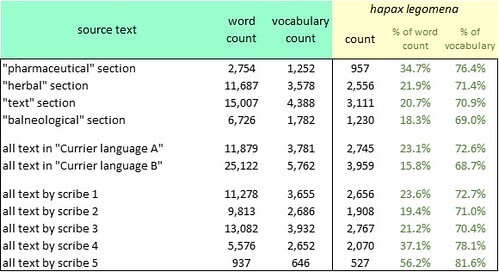

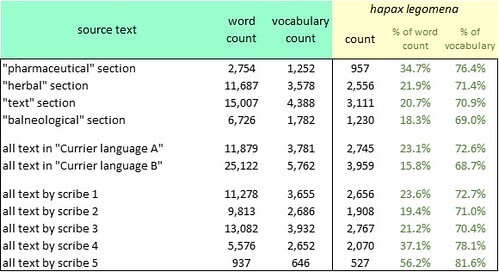

Below is a summary of the incidence of hapax legomena in the major thematic sections of the manuscript; in the two "languages" identified by Prescott Currier; and in the pages written by the five scribes identified by Dr Lisa Fagin Davis.

The incidence of hapax legomena in the Voynich manuscript, by section, "language" and scribe. Author's analysis.

These calculations show that the incidence of hapax legomena, as a percentage of the word count, is generally in the range 15 to 37 percent, depending on which element of the manuscript we measure. The longer the chunk of text, the lower the incidence of hapax legomena. This is as we should expect, since a longer text gives more opportunity for a word to be re-used.

The outlier is the work of Scribe 5, who wrote five pages of the "herbal" section and one page of the "text" section.

As a comparator, I have only one example of presumed gibberish: the compilation of "angelic messages" written by John Dee and Edward Kelley between 1581 and 1583 (as cited by Boxer). This document, of about 4,000 words, has an incidence of hapax legomena of about 57 percent of the word count.

Against this, the Voynich manuscript generally gives the impression of meaningful content, however we slice it: with the possible exception of the contribution of Scribe 5.

The "truncation effect"

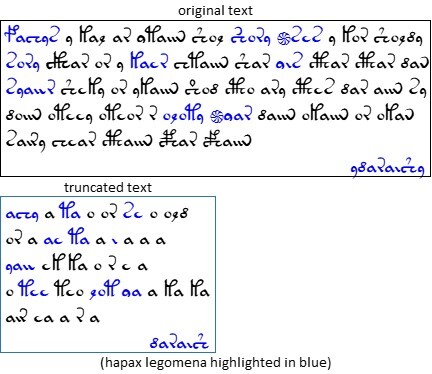

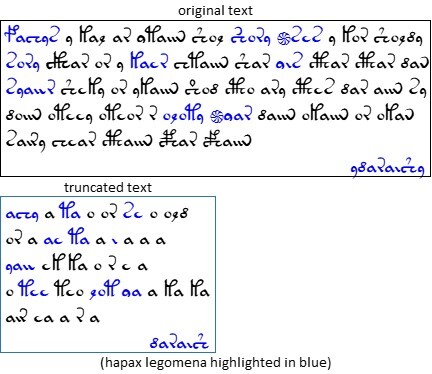

In one set of tests, on the text in Language B, I examined the impact of removing the initial and final glyphs of every "word". This made all the "words" of one or two glyphs disappear; and shortened all the remaining "words" by two glyphs. An example is shown below.

Voynich manuscript, page f1r, lines 1-6: identification of hapax legomena. Author's analysis.

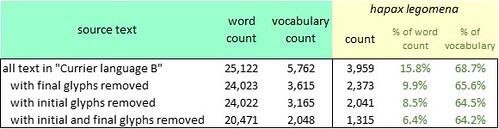

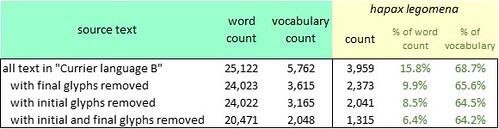

Voynich manuscript: the incidence of hapax legomena after removing initial or final glyphs. Author's analysis.

The removal of initial or final glyphs, or both, had the effect of reducing the incidence of hapax legomena: that is, increasing the probability that there was meaning in the remaining text. I was inclined to call this phenomenon "the truncation effect".

In a natural language, to some extent this effect should be expected. For example if a document in English contained the words "fonder", "wonder" and "yonder", after removal of the initial letter the three would become "onder". If any of these three words had been a hapax legomenon, it would cease to be so; and the incidence of hapax legomena would probably decrease.

The order of the letters

I thought that perhaps we could use the "truncation effect" for another purpose. Perhaps we could determine whether, when the Voynich scribes mapped from the presumed natural languages to glyphs, they preserved the order of the letters within words.

In natural languages, what we call a meaningful text is made up of words in which the letters are in their original order. In the Voynich manuscript, we have reason to suspect that this is not the case. This will be evident from a reading of two technical papers on the Voynich manuscript:

Them's not the breaks

With regard to the Voynich manuscript, we have seen that we can remove all the initial glyphs, and all the final glyphs, and the text somehow appears to retain whatever meaning it may possess. My first reaction was that the interior glyphs held the meaning of the text, and that the initial and final glyphs were something like punctuation, or maybe junk.

But removing glyphs from Voynich "words" makes those "words" impossibly short, by comparison with natural languages. In the v101 transliteration, the average length of "words" is 3.90 glyphs; if we remove two glyphs from each "word", the average drops to 2.44 glyphs. To my knowledge, there is no natural language in which the words are that short.

If the initial and final glyphs are really punctuation or junk, it is an inescapable inference that the Voynich "words" are not words. Prescott Currier said as much, at Mary D'Imperio's seminar in 1976. Specifically, the spaces are not word breaks.

By analogy, let's imagine that we wished to hide the Gettysburg Address within brackets of junk letters. Firstly we would insert spaces at random points between the letters. Thus, the first two words:

An alphabetic cipher?

If the initial and final glyphs are not punctuation or junk, then another possibility is that they are indicators of an alphabetic sorting, of the kind that D'Imperio's and Zattera’s papers imply. In English, we expect that after an alphabetic sorting, words will often begin with a or e, and will often end in t or u.

Likewise, in the Voynich manuscript, "words" often begin with the v101 glyphs {4o} or {o} or {9}, and often end with the glyph {9}. This would be the case if {4o} and {o} were among the first letters of the Voynich “alphabet” and {9} was both among the first and among the last; and if the glyphs in every word were in “alphabetic” order. This phenomenon found expression in Zattera's "slot alphabet", in which, for example, {4} is invariably in slot 0, {o} is usually in slot 1, and {9} can be in slot 1 or slot 11.

Further research

To me it seems that the "truncation effect" needs testing on an appropriate document. We need a document of a comparable length to the Voynich manuscript, say at least 40,000 words. Also, as long as we assume a medieval European provenance for the text (which I think is a reasonable assumption), we might start with a document in medieval Latin or Italian. I am working on Dante’s La Divina Commedia and will report in another post.

As Alexander Boxer demonstrated in his presentation to the Voynich 2022 conference, the prevalence of hapax legomena can be an indicator of the presence or absence of semantic meaning. Specifically, for a document of a given length, a lower incidence of hapax legomena is indicative of meaningful content. A higher incidence is a "fingerprint" of gibberish.

Below is a summary of the incidence of hapax legomena in the major thematic sections of the manuscript; in the two "languages" identified by Prescott Currier; and in the pages written by the five scribes identified by Dr Lisa Fagin Davis.

The incidence of hapax legomena in the Voynich manuscript, by section, "language" and scribe. Author's analysis.

These calculations show that the incidence of hapax legomena, as a percentage of the word count, is generally in the range 15 to 37 percent, depending on which element of the manuscript we measure. The longer the chunk of text, the lower the incidence of hapax legomena. This is as we should expect, since a longer text gives more opportunity for a word to be re-used.

The outlier is the work of Scribe 5, who wrote five pages of the "herbal" section and one page of the "text" section.

As a comparator, I have only one example of presumed gibberish: the compilation of "angelic messages" written by John Dee and Edward Kelley between 1581 and 1583 (as cited by Boxer). This document, of about 4,000 words, has an incidence of hapax legomena of about 57 percent of the word count.

Against this, the Voynich manuscript generally gives the impression of meaningful content, however we slice it: with the possible exception of the contribution of Scribe 5.

The "truncation effect"

In one set of tests, on the text in Language B, I examined the impact of removing the initial and final glyphs of every "word". This made all the "words" of one or two glyphs disappear; and shortened all the remaining "words" by two glyphs. An example is shown below.

Voynich manuscript, page f1r, lines 1-6: identification of hapax legomena. Author's analysis.

Voynich manuscript: the incidence of hapax legomena after removing initial or final glyphs. Author's analysis.

The removal of initial or final glyphs, or both, had the effect of reducing the incidence of hapax legomena: that is, increasing the probability that there was meaning in the remaining text. I was inclined to call this phenomenon "the truncation effect".

In a natural language, to some extent this effect should be expected. For example if a document in English contained the words "fonder", "wonder" and "yonder", after removal of the initial letter the three would become "onder". If any of these three words had been a hapax legomenon, it would cease to be so; and the incidence of hapax legomena would probably decrease.

The order of the letters

I thought that perhaps we could use the "truncation effect" for another purpose. Perhaps we could determine whether, when the Voynich scribes mapped from the presumed natural languages to glyphs, they preserved the order of the letters within words.

In natural languages, what we call a meaningful text is made up of words in which the letters are in their original order. In the Voynich manuscript, we have reason to suspect that this is not the case. This will be evident from a reading of two technical papers on the Voynich manuscript:

• Mary D'Imperio's paper "An Application of PTAH to the Voynich Manuscript", written for the National Security Agency around 1978 but classified until 2009;D'Imperio and Zattera made a compelling case that the "words" in the Voynich manuscript had a specific interior sequence of glyphs: what D'Imperio called "the five states"; what Zattera called a “slot alphabet”; and what, in a natural language, we would call an alphabetical order.

• Massimilano Zattera’s paper “A New Transliteration Alphabet Brings New Evidence of Word Structure and Multiple "Languages" in the Voynich Manuscript”, presented at the Voynich 2022 conference.

Them's not the breaks

With regard to the Voynich manuscript, we have seen that we can remove all the initial glyphs, and all the final glyphs, and the text somehow appears to retain whatever meaning it may possess. My first reaction was that the interior glyphs held the meaning of the text, and that the initial and final glyphs were something like punctuation, or maybe junk.

But removing glyphs from Voynich "words" makes those "words" impossibly short, by comparison with natural languages. In the v101 transliteration, the average length of "words" is 3.90 glyphs; if we remove two glyphs from each "word", the average drops to 2.44 glyphs. To my knowledge, there is no natural language in which the words are that short.

If the initial and final glyphs are really punctuation or junk, it is an inescapable inference that the Voynich "words" are not words. Prescott Currier said as much, at Mary D'Imperio's seminar in 1976. Specifically, the spaces are not word breaks.

By analogy, let's imagine that we wished to hide the Gettysburg Address within brackets of junk letters. Firstly we would insert spaces at random points between the letters. Thus, the first two words:

four scorewould become, for example:

f ou rs c or eWe would then add random letters before and after each block of letters. We would choose the initial letter randomly from the first five letters of the Latin alphabet (a through e) and the final letter randomly from the last five (v through z). The result would be somewhat as follows:

cfy douy crsw acv borx aey.Something like this could be occurring in the Voynich manuscript, where a small set of glyphs predominates as initial glyphs, and another small set predominates as final glyphs.

An alphabetic cipher?

If the initial and final glyphs are not punctuation or junk, then another possibility is that they are indicators of an alphabetic sorting, of the kind that D'Imperio's and Zattera’s papers imply. In English, we expect that after an alphabetic sorting, words will often begin with a or e, and will often end in t or u.

Likewise, in the Voynich manuscript, "words" often begin with the v101 glyphs {4o} or {o} or {9}, and often end with the glyph {9}. This would be the case if {4o} and {o} were among the first letters of the Voynich “alphabet” and {9} was both among the first and among the last; and if the glyphs in every word were in “alphabetic” order. This phenomenon found expression in Zattera's "slot alphabet", in which, for example, {4} is invariably in slot 0, {o} is usually in slot 1, and {9} can be in slot 1 or slot 11.

Further research

To me it seems that the "truncation effect" needs testing on an appropriate document. We need a document of a comparable length to the Voynich manuscript, say at least 40,000 words. Also, as long as we assume a medieval European provenance for the text (which I think is a reasonable assumption), we might start with a document in medieval Latin or Italian. I am working on Dante’s La Divina Commedia and will report in another post.

Published on March 25, 2024 22:32

•

Tags:

alexander-boxer, hapax-legomena, voynich, zattera

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers