Filling in the Gaps

When I was in 6th grade, we engaged in a big archeology project with another classroom. Each room’s job was to invent an ancient culture in detail and then create a variety of artifacts to pack up and send across the hallway, for the other room to “dig up” and interpret. My class decided that our ancient culture would be all about cheese. I have no idea why we were all about cheese, but we were committed. We even visited a local cheese shop to learn obscure and interesting cheese names and facts. As a class, we sketched out all the ways our society worked, and then we broke up into table groups to take on roles within that society and start creating half-broken artifacts representing the lives we had lived—to both inform and confuse our junior archeologists across the hall.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I don’t remember what the result of the project was—what the other classroom made of what we created, or what they sent over to us to interpret. But the fact of the project has stayed with me forever, along with the lesson we learned, that our understanding of the past is built of bits and pieces—T.S. Eliot’s “heap of broken images.”

We have 14 plays from ancient Greece, along with teasing references in other literary works to a few other plays and playwrights. But there were hundreds of plays, and most of them are lost. Do we really think that our 14 paint an accurate and complete picture of what “theater” was, in that place and time? Do we assume that whatever was lost was lose-able, because it was less worthy, or even less representative? The 14 plays survived because they were popular and had many copies made of them—but they also survived out of sheer chance and luck.

When Hilary Mantel wrote her wonderful Wolf Hall trilogy about Thomas Cromwell and Henry VIII, it outraged a lot of people who had grown up seeing Cromwell as the bad guy and Thomas More as the saint and martyr. Count me among them—I grew up watching A Man for All Seasons, and Paul Scofield was definitely my dude—not Leo McKern. But in Mantel’s novel, Cromwell was the proto-modern man—capable, rational, far-sighted, personally ambitious, unafraid to question the past, suspicious of superstition. More, in her telling, was a cold, bloodthirsty, religious zealot—and kind of a prig. He was the past; Cromwell was the future. In her telling, Cromwell’s mind is the mind that created the world we live in.

So, who’s right? Historians complained that the record proved Mantel hysterically wrong. But what is the record? Surviving letters, speeches, and proclamations written by those who survived Cromwell and defeated him: history as written by the winners. We know what he did (some of what he did), but do we know why he did what he did? Do we have it in his words? Do we know his mind? Do we know it all?

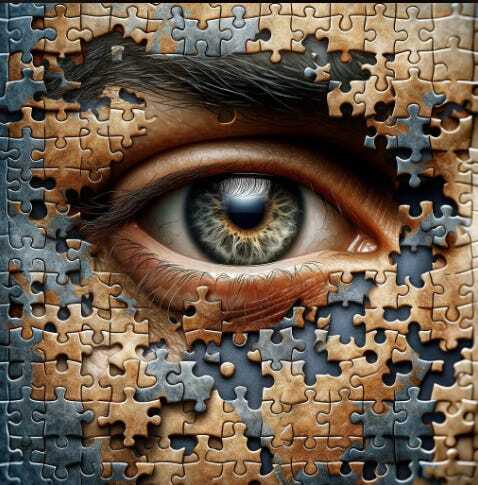

I think back to our archeology project in sixth grade. We created an incomplete jigsaw puzzle, and we asked the other classroom to use the pieces we gave them to help them fill in the gaps. History is like that—and sometimes, we have very few pieces to work with. How do we know—how do we know—that the pieces we create to fill in the gaps accurately represent the material that once used to be there? It makes me think of the frog DNA that the scientists in Jurassic Park use to fill in the gaps for the dinosaurs they’re trying to recreate. Those pieces do the trick—they create a living creature that’s a lot like a dinosaur—but they don’t recreate what actually roamed the earth; they make something slightly different.

Something similar happens in the here and now, in our every waking moment. As Daniel Kahneman writes in his amazing book, Thinking Fast and Slow, our eyes take in more visual data from our immediate environment than our brains are capable of processing in real time. We think we’re walking around inside a complete and accurate visual representation of the world, but…we don’t know that for a fact. The capacity of our brain to process information, and our working memory’s limited capacity to hold information, all put constraints on how much raw, visual data actually gets consciously perceived, processed, and acted on. We construct a simplified model of reality based on selective sampling of visual details. Then we fill in the gaps. When reality seems to fit, and for as long as it seems to fit, we don’t challenge or change the model we’ve built. When reality conflicts, we make adjustments. This has been tested and confirmed, over and over again—sometimes in amusing ways (like quickly swapping one blond woman for another to see if the man she’s been speaking with realizes there’s a new person in front of him) (TLDR: he doesn’t).

When we test our perception against facts, we have a chance to readjust the model of the world that we’ve constructed. We get to blink and realize that the woman in front of us is not the woman we thought she was. But if we filter and limit the information that comes in, all we do is reinforce the model we have. If we only read and hear things that reinforce our pre-existing ideas, we have no chance to find out if our ideas are still true. We all know about that; it’s called confirmation bias. But this kind of bias leads to something called the ladder of inference, in which we become trapped in an ever-tightening noose that hardens our perceptions and pushes us to more extreme positions. We live our lives in a constant state of “it is,” instead of entertaining an occasional “what if?” that might force us to think differently.

I think it’s important to realize that this doesn’t apply only to some of us but not to the rest of us. This isn’t about Right vs. Left, or urban vs. rural, or college-educated vs. GED. This affects all of us. It’s simply how our brains work. The world we live in is not exactly, not precisely, not completely, the world we perceive in our individual minds, the world we tell ourselves stories about. There are gaps. And even when we work to close the gaps, the world is constantly changing, leaving our models behind.

It’s a little terrifying—a little science-fiction-y, maybe, but there it is. Our bodies exist together in the same world, but our minds do not—not unless we take action to learn more about the world and challenge what we think it is; not unless we talk to each other about how we perceive the world and listen to our neighbors about how they perceive it.

As it turns out, this is the essence of democracy and self-rule. This is what is required to make democracy work. Long before we had a revolution and a Constitution, we had town meetings. We came together in small groups and said, “this is what I see; what do you see?” Dictatorship does not need such things—it radically does not want them. Dictatorship says, “I am in charge, and the way I see the world is what the world will be.”

The Thomas More of A Man for All Seasons is still a hero to me, because he says to his king: you have the right to rule the nation, but you cannot rule my mind or my soul. I do not know how accurate this depiction is to the real man who died in 1535, but he is real to me. And when I see Alexei Navalny returning to Russia and saying essentially the same thing to his king, I know that there is truth there.

I don’t know how we can claim to be free men and women if we don’t do the work of dispelling ourselves of superstition, illusion, and bias—to see the world around us as it actually is, as clearly as we possibly can. So many bad people benefit from our unwillingness to do this hard work. And it is hard work—hard, constant work.

As George Orwell said: “To see what is in front of one's nose needs a constant struggle.” But, as our modern man for all seasons, Alexei Navalny, said, shortly before his death: "You're not allowed to give up."

Scenes from a Broken Hand

- Andrew Ordover's profile

- 44 followers