Voynich Reconsidered: an alphabetic cipher?

In other articles on this platform, I have referred to my working assumptions on the Voynich manuscript (with which reasonable people may disagree), which include the following:

In 1978 Mary D’Imperio wrote a technical article (not published until decades later) in which she observed that the Voynich glyphs could be classified by their position within the "word". She identified between five and seven classes of glyph, to which she gave labels like "beginners", "middles" and "enders".

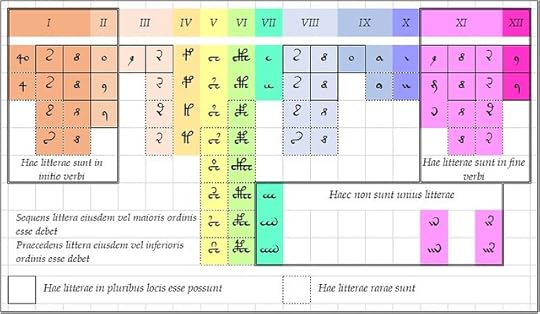

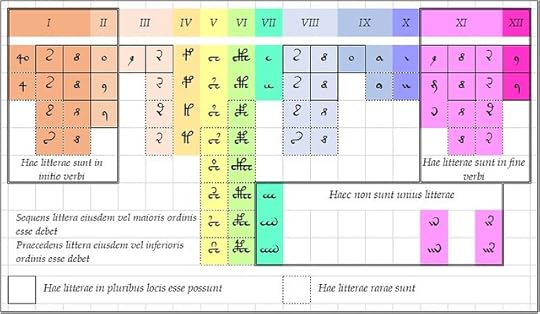

Massimiliano Zattera's paper at the Voynich 2022 conference, on what he called the "slot alphabet", confirmed and elaborated D'Imperio's findings. With much more computing power at his disposal than D'Imperio could have dreamed of, Zattera identified twelve classes of glyph. He demonstrated that there was an almost inflexible order in which the glyphs could appear within a Voynich "word": like soldiers grouped by their rank in the army.

An imagined wall chart for the scribes of the Voynich manuscript. Image credit: author, based on Zattera's "slot alphabet".

To my mind, D'Imperio's and Zattera's findings encourage us to imagine an encipherment based on a simple and practicable instruction to the scribes: that after the transcription from precursor letters to glyphs, they should re-order the glyphs in each "word", according to a prescribed sequence.

The Ozymandias manuscript

In English, for example, if we take the first line of Shelley's Ozymandias:

Our hypothetical decoders of the Ozymandias manuscript would surely notice that "words" often began with the glyph "a", and often ended with the glyph "u" or "v". They would wonder, as Prescott Currier wondered in 1976, whether the ending of a "word" somehow influenced the beginning of the next "word". They would observe, as Currier observed, that there was no natural language in which this phenomenon occurred. They would be wrong: that phenomenon was a correlation but not an influence.

But if we had a reverse mapping of Voynich text to any natural language, lovers of crossword puzzles or Scrabble (in that language) could probably determine quickly whether there was any embedded meaning or narrative.

The Sukhotin algorithm

In other posts on this platform, I have proposed that, if the Voynich "words" correspond to precursor words, and if the Voynich glyphs are in the same order as the presumed precursor letters, we could use the Sukhotin algorithm to identify vowels. More precisely, we could identify the glyphs that most probably represent vowels in the precursor documents.

The algorithm is based on Sukhotin's insight that in natural languages, vowels and consonants alternate more often than not.

But if the glyphs have undergone re-ordering, the juxtaposition of vowels and consonants has been lost, and the Sukhotin algorithm will break down.

In this case, what is preserved is only the frequency distribution of the glyphs; and at best, we could hope to match five of the seven or eight most frequent glyphs with the five vowels typically found in European languages. Once we have identified five vowel-glyphs, we can assume that the remaining glyphs represent consonants, and we can match them with precursor consonants, using tools such as frequency analysis.

Recurring letters

However, a re-ordering of the glyphs within "words" will still preserve the number of glyphs in each "word"; and specifically, the number of glyphs which recur within the "word".

As we saw in the example above from Ozymandias, an alphabetic sorting of letters within words will assemble the recurring letters, and will often produce strings of double or triple letters. For example, the word "traveller" yielded the strings "ee", "ll" and "rr".

We see a similar phenomenon in the Voynich manuscript. In the v101 transliteration, there are at least eleven glyphs, conventionally viewed as single glyphs, that look as if they could represent or contain doubled or tripled letters. There are four that are actually viewed in v101 as doubled or tripled.

v101 glyphs or glyph strings that could be interpreted as doubled or tripled letters. Author's analysis.

In these cases, we have to wonder if these apparent doubles and triples are simply a consequence of a re-ordering of the glyphs.

This hypothesis should be amenable to testing. We can select some large texts in medieval natural languages, for example Dante's La Divina Commedia; apply an alphabetic re-ordering of the letters in each word (for which online tools exist); in the re-ordered text, count the occurrences of double and triple letters; and see how the frequencies compare with those in the Voynich manuscript.

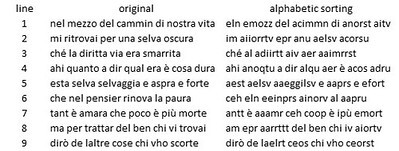

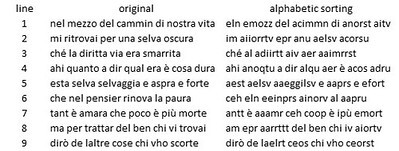

Below is a very small example, drawn from the first nine lines of La Divina Commedia, Gutenberg edition. This is written in a somewhat modernised Italian; in the first printed edition of 1472, the first line was "Nel mezo delcamin dinrã uita". In the Gutenberg version, there are no occurrences of the string "aa"; in the sorted version, there are six. If medieval Italian had been a precursor of the Voynich manuscript, we might suspect that the glyph {c} represented the letter "a"; and that glyphs or glyph strings such as {1}, {C} or {cc} had been mapped from words containing multiple "a"s.

La Divina Commedia, Canto 1, lines 1-9: Gutenberg version, and with letters sorted alphabetically within words. Author's analysis.

On my further testing of this hypothesis, more later.

* that the manuscript was derived from precursor documents in a natural language or languagesI considered the possibility that the producer's instructions to the scribes included some form of encipherment. I like the idea of Dr Jiří Milička, of the Faculty of Comparative Linguistics at Charles University, that any system for enciphering a fifteenth-century document should be relatively simple. I have therefore thought about ciphers which would be easy to administer, but difficult to decode.

* that the author or producer of the manuscript engaged a team of scribes, to whom he or she gave simple instructions for the transliteration from letters to glyphs.

In 1978 Mary D’Imperio wrote a technical article (not published until decades later) in which she observed that the Voynich glyphs could be classified by their position within the "word". She identified between five and seven classes of glyph, to which she gave labels like "beginners", "middles" and "enders".

Massimiliano Zattera's paper at the Voynich 2022 conference, on what he called the "slot alphabet", confirmed and elaborated D'Imperio's findings. With much more computing power at his disposal than D'Imperio could have dreamed of, Zattera identified twelve classes of glyph. He demonstrated that there was an almost inflexible order in which the glyphs could appear within a Voynich "word": like soldiers grouped by their rank in the army.

An imagined wall chart for the scribes of the Voynich manuscript. Image credit: author, based on Zattera's "slot alphabet".

To my mind, D'Imperio's and Zattera's findings encourage us to imagine an encipherment based on a simple and practicable instruction to the scribes: that after the transcription from precursor letters to glyphs, they should re-order the glyphs in each "word", according to a prescribed sequence.

The Ozymandias manuscript

In English, for example, if we take the first line of Shelley's Ozymandias:

I met a traveller from an antique land,a simple alphabetic re-ordering of the letters produces the following sequence:

I emt a aeellrrtv fmor an aeinqtu adln.Someone who did not know the English language or the Latin script, and who sought meaning in this sequence, would have a task comparable with that which we face with the Voynich manuscript.

Our hypothetical decoders of the Ozymandias manuscript would surely notice that "words" often began with the glyph "a", and often ended with the glyph "u" or "v". They would wonder, as Prescott Currier wondered in 1976, whether the ending of a "word" somehow influenced the beginning of the next "word". They would observe, as Currier observed, that there was no natural language in which this phenomenon occurred. They would be wrong: that phenomenon was a correlation but not an influence.

But if we had a reverse mapping of Voynich text to any natural language, lovers of crossword puzzles or Scrabble (in that language) could probably determine quickly whether there was any embedded meaning or narrative.

The Sukhotin algorithm

In other posts on this platform, I have proposed that, if the Voynich "words" correspond to precursor words, and if the Voynich glyphs are in the same order as the presumed precursor letters, we could use the Sukhotin algorithm to identify vowels. More precisely, we could identify the glyphs that most probably represent vowels in the precursor documents.

The algorithm is based on Sukhotin's insight that in natural languages, vowels and consonants alternate more often than not.

But if the glyphs have undergone re-ordering, the juxtaposition of vowels and consonants has been lost, and the Sukhotin algorithm will break down.

In this case, what is preserved is only the frequency distribution of the glyphs; and at best, we could hope to match five of the seven or eight most frequent glyphs with the five vowels typically found in European languages. Once we have identified five vowel-glyphs, we can assume that the remaining glyphs represent consonants, and we can match them with precursor consonants, using tools such as frequency analysis.

Recurring letters

However, a re-ordering of the glyphs within "words" will still preserve the number of glyphs in each "word"; and specifically, the number of glyphs which recur within the "word".

As we saw in the example above from Ozymandias, an alphabetic sorting of letters within words will assemble the recurring letters, and will often produce strings of double or triple letters. For example, the word "traveller" yielded the strings "ee", "ll" and "rr".

We see a similar phenomenon in the Voynich manuscript. In the v101 transliteration, there are at least eleven glyphs, conventionally viewed as single glyphs, that look as if they could represent or contain doubled or tripled letters. There are four that are actually viewed in v101 as doubled or tripled.

v101 glyphs or glyph strings that could be interpreted as doubled or tripled letters. Author's analysis.

In these cases, we have to wonder if these apparent doubles and triples are simply a consequence of a re-ordering of the glyphs.

This hypothesis should be amenable to testing. We can select some large texts in medieval natural languages, for example Dante's La Divina Commedia; apply an alphabetic re-ordering of the letters in each word (for which online tools exist); in the re-ordered text, count the occurrences of double and triple letters; and see how the frequencies compare with those in the Voynich manuscript.

Below is a very small example, drawn from the first nine lines of La Divina Commedia, Gutenberg edition. This is written in a somewhat modernised Italian; in the first printed edition of 1472, the first line was "Nel mezo delcamin dinrã uita". In the Gutenberg version, there are no occurrences of the string "aa"; in the sorted version, there are six. If medieval Italian had been a precursor of the Voynich manuscript, we might suspect that the glyph {c} represented the letter "a"; and that glyphs or glyph strings such as {1}, {C} or {cc} had been mapped from words containing multiple "a"s.

La Divina Commedia, Canto 1, lines 1-9: Gutenberg version, and with letters sorted alphabetically within words. Author's analysis.

On my further testing of this hypothesis, more later.

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers