A Novice’s Introduction to Victorian Carriages, Part 2

In Part 1, I looked at two very popular carriages: the dog-cart and the hansom cab. Both of those typical have only two-wheels, though we saw that, sometimes, a four-wheel vehicle was called a “dog-cart.” Now, we look at two more carriages, both four-wheelers.

Apparently, “phaeton” was simply a name for almost any four-wheeled carriage, and there was quite a variety of phaetons. Here, I look at the brougham and the victoria.

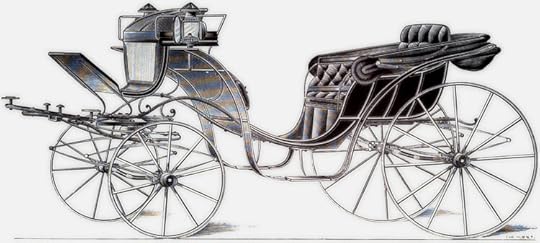

Being Seen in a Brougham Another of the lovely illustrations from Samuel Sidney’s

The Book of the Horse

Another of the lovely illustrations from Samuel Sidney’s

The Book of the Horse

“Dorian, you will come with me. I am so sorry, Basil, but there is only room for two in the brougham. You must follow us in a hansom.” So says Lord Henry in Oscar Wilde’s A Picture of Dorian Grey (1890), and this helps us better see the picture being painted by Victorian authors who specify a brougham. It’s limited to two passengers. In fact, expert on all things equestrian Samuel Sidney explains that the later models “barely afford a place for the travelling-bag of more than one passenger.” Cozy, then. And the lighter load meant it could be drawn by only one horse, which I sense was a frequent sight, but there might be two.

It’s also what was called a “close carriage,” meaning riders were protected from the weather by an enclosure. One might wonder if it got stuffy in there! Well, Sidney tells us this vehicle was warm in winter and cool in summer. But they might’ve been “stuffy” in the sense that broughams were typically owned by the upper-crust, Lord Henry and the like. Sidney continues: “In the Park [presumably, London’s Hyde Park], and at other assemblies of the fashionable, the windows of a brougham are so ‘hung on the line’ as to present a fair face at the very best point of view for admiration and for conversation.” In other words, these were something of a high-fashion accessory for those wanting to be noticed. And this is why a 1901 short story titled “Wanted: for Desertion” opens with a police officer at a posh public performance using “his massive body as a buffer between brougham-windows and plebian curiosity.” Dare I say, one’s desire to be noticed hardly extends to being noticed by the riffraff.

Being Even More Seen in a Victoria From an impressive series of 1886 “fashion plates” published in a New York magazine called The Hub

From an impressive series of 1886 “fashion plates” published in a New York magazine called The HubAs with the brougham, a victoria was light enough for only one horse, though more could be added. This, too, is vehicle for displaying one’s wealth. As Sidney points out, the victoria was designed to show off — not just one’s face — but one’s entire regalia, “from the crown of her head to the sole of her foot.” It is “an expensive carriage to convey two persons — a carriage only available for ornamental purposes, for it cannot be used at night, or in dirty weather, or in the country, or anywhere except for the Park, for a little shopping and a little visiting.” The illustration above says as much. That flip-up roof, often called a “calash,” might guard against the Sun — but not much more.

In Part 1, I make a quick mention of Bram Stocker’s Dracula (1897). In this novel of many narrative perspectives, one relevant moment comes through Mina’s eyes. She and Jonathan are strolling near Hyde Park, when something scary happens:

I was looking at a very beautiful girl, in a big cart-wheel hat, sitting in a victoria outside Guiliano’s, when I felt Jonathan clutch my arm so tight that he hurt me, and he said under his breath: "My God!"Yet Jonathan isn’t reacting to the passenger in the victoria (in front of Carlo Giuliano’s jewelry shop). Instead, he has spotted “a tall, thin man, with a beaky nose and black moustache and pointed beard, who was also observing the pretty girl.” The man has “big white teeth” that are “pointed like an animal’s.” As does Jonathan, readers are pretty sure they recognize this toothy chap from earlier in the novel. Now, let’s chart things here: upon observing the woman in the victoria, Mina next observes Jonathan observing Dracula observing the woman in the victoria. No wonder Stoker specifies that particular kind of carriage. The victoria wasn’t merely a mode of transportation. It was a mode of public appearance. It fits the scene perfectly.

I wonder, though, if broughams and victorias were more status-symbolic in metropolitan areas, especially London, than in the country. In Driving (1889), Henry Charles Beaufort contends: “A brougham, a victoria, or a waggonette, may be put down as the cheapest form of carriage procurable for general purposes.” He then qualifies this, though, by suggesting that those wanting something fancier can find such vehicles (and the horses pulling them) at “fancy prices.”

There were other kinds of phaetons that pop up in Victorian fiction, too, and I’ll discuss two more in Part 3. If you have anything to add — or to contest — please do so in the comments.

— Tim

GO TO VICTORIAN CARRIAGES, PART 1