William Faulkner’s introduction to Sanctuary

The best character William Faulkner ever created was himself, William Faulkner. The flying injury, Rowan Oak, the photographs, the guest roles, the interviews, scraps of footage, the Nobel Prize speech. Perfect.

In 1929 William Faulkner, then age 31, wrote Sanctuary, which has one of the trashiest loglines ever: Ole Miss coed Temple Drake ends up the sex slave of a gangster named Popeye. Here at Helytimes we won’t go into detail of what exactly Popeye does, we leave that to lesser publications like The Washington Post:

what interested him chiefly about this horrific event was “how all this evil flowed off her like water off a duck’s back.” In his haste to make a best seller, he crammed in all he had seen and heard about whorehouses, rapes and kidnappings.

This was a ripped from the headlines story based on a true crime case. As a Mississippi crime book complete with courtroom scenes, it’s kind of a proto-Grisham.

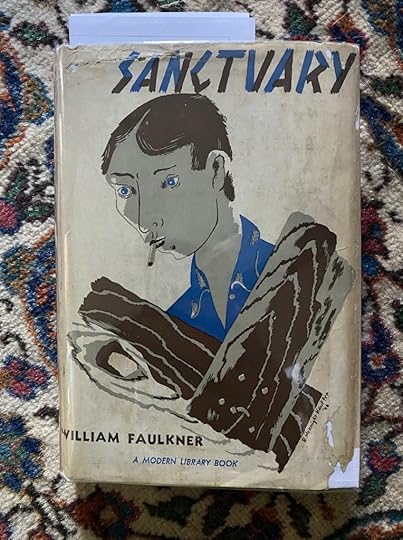

Sanctuary was published by Jonathan Cape in 1931. Then in 1932 the Modern Library put out a new edition with a new introduction by Faulkner. Scholars since have apparently debunked everything Faulkner claimed in this introduction as fabulations and lies but so what? In a way that makes it even better. A work of autofiction.

We couldn’t find this introduction online so we got a used copy and scanned it in, it’s out of copyright (we believe?).

INTRODUCTION

THIS BOOK WAS WRITTEN THREE YEARS AGO. To me it is a cheap idea, because it was deliberately conceived to make money. I had been writing books for about five years, which got published and not bought. But that was all right. I was young then and hard-bellied. I had never lived among nor known people who wrote novels and stories and I suppose I did not know that people got money for them. I was not very much annoyed when publishers refused the mss. now and then. Because I was hard-gutted then. I could do a lot of things that could earn what little money I needed, thanks to my father’s un- failing kindness which supplied me with bread at need despite the outrage to his principles at having been of a bum progenitive.

Then I began to get a little soft. I could still paint houses and do carpenter work, but I got soft. I began to think about making money by writing. I began to be concerned when magazine editors turned down short stories, concerned enough to tell them that they would buy these stories later anyway, and hence why not now. Meanwhile, with one novel completed and consistently refused for two years, I had just written my guts into The Sound and the Fury though I was not aware until the book was pub- lished that I had done so, because I had done it for pleasure. I believed then that I would never be published again. I had stopped thinking of myself in publishing terms.

But when the third mss., Sartoris, was taken by a publisher and (he having refused The Sound and the Fury) it was taken by still another publisher, who warned me at the time that it would not sell, I began to think of myself again as a printed object. I began to think of books in terms of possible money. I decided I might just as well make some of it myself. I took a little time out, and speculated what a person in Mississippi would believe to be current trends, chose what I thought was the right answer and invented the most horrific tale I could imagine and wrote it in about three weeks and sent it to Smith, who had done The Sound and the Fury and who wrote me immediately. ”Good God, I can’t publish this. We’d both be in jail.” So I told Faulkner, “You’re damned. You’ll have to work now and then for the rest of your life.” That was in the summer of 1929. I got a job in the power plant, on the night shift, from 6 P.M. to 6 A.M., as a coal passer. I shoveled coal from the bunker into a wheel- barrow and wheeled it in and dumped it where the fireman could put it into the boiler. About 11 o’clock the people wuuld be going to bed, and so it did not take so much steam. Then we could rest, the fireman and I. He would sit in a chair and doze. I had invented a table out of a wheel- barrow in the coal bunker, just beyond a wall from where a dynamo ran. It made a deep, constant humming noise. There was no more work to do until about 4 A.M., when we would have to clean the fires and get up steam again. On these nights, between 12 and 4, I wrote As I Lay Dying in six weeks, without changing a word. I sent it to Smith and wrote him that by it I would stand or fall.

I think I had forgotten about Sanctuary, just as you might forget about anything made for an immediate purpose, which did not come off. As I Lay Dying was published and I didn’t remember the mss. of Sanctuary until Smith sent me the galieys. Then I saw that it was so terrible that there were but two things to do: tear it up or rewrite it. I thought again, “It might sell; maybe 10,000 of them will buy it.” So I tore the galleys down and rewrote the book. It had been already set up once, so I had to pay for the

privilege of rewriting it, trying to make out of it something which would not shame The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying too much and I made a fair job and I hope you will buy it and tell your friends and I hope they will buy it too.

WILLIAM FAULKNER. New York, 1932.

Happy New Year to all 6,722 of our loyal readers, all over the globe.