“Where to look for the threads”

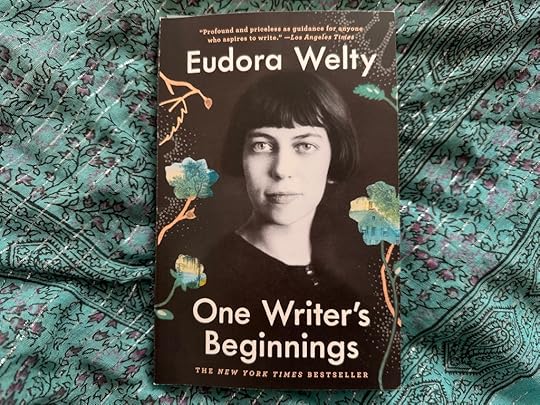

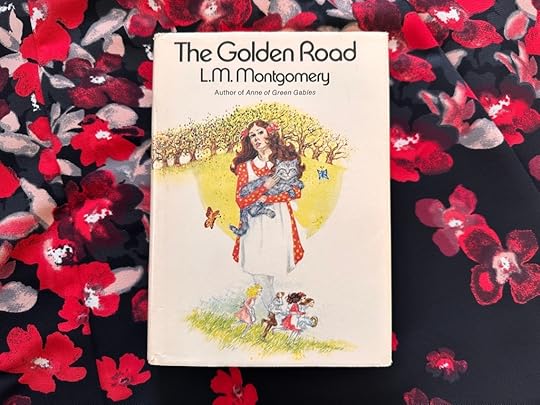

I’ve been reading Eudora Welty recently. I started with One Writer’s Beginnings, which was a present from my sister Bethie, and I loved it so much that I immediately ordered her collected stories and essays. Reading Welty’s memoir and L.M. Montgomery’s The Golden Road around the same time made it possible to see links between the two writers that I might otherwise have missed.

Welty says, “Writing fiction has developed in me an abiding respect for the unknown in a human lifetime and a sense of where to look for the threads, how to follow, how to connect, find in the thick of the tangle what clear line persists. The strands are all there: to the memory nothing is ever really lost.”

These lines prompted me to return to the last pages of The Golden Road, in which the Story Girl’s father speaks of his love for her late mother: “How I loved her! How happy we were! But he who accepts human love must bind it to his soul with pain, and she is not lost to me. Nothing is ever really lost to us as long as we remember it.”

I chose this turquoise scarf for the background not just because it matches the cover of the book, but because I bought it in Boston the summer I was fourteen, when I was on my way to Welty’s hometown of Jackson, Mississippi, to spend a week volunteering for a charity similar to Habitat for Humanity.

I thought of the Story Girl’s love of roads when I read Welty’s account of travelling with her parents, with her mother giving directions while her father drove: “‘This doesn’t surprise me at all,’ she’d say as Daddy backed up a mile or so into our own dust on a road that had petered out. ‘I could’ve told you a road that looked like that had little intention of going anywhere.’”

Do you remember the discussion of fairyland in The Story Girl? Bev, the narrator, says the Story Girl is right that fairyland exists, but only children know how to get there, and when they get older they forget—except for “singers and poets and artists and story-tellers.”

Welty writes that “Children, like animals, use all their sense to discover the world. Then artists come along and discover it the same way, all over again. Here and there, it’s the same world. Or now and then we’ll hear from an artist who’s never lost it.”

I hadn’t known before that Welty worked as a photographer in the 1930s, taking pictures of daily life in Mississippi. I enjoyed reading her description of what she learned from photography:

I learned in the doing how ready I had to be. Life doesn’t hold still. A good snapshot stopped a moment from running away. Photography taught me that to be able to capture transience, by being ready to click the shutter at the crucial moment, was the greatest need I had. Making pictures of people in all sorts of situations, I learned that every feeling waits upon its gesture; and I had to be prepared to recognize this moment when I saw it. These were things a story writer needed to know. And I felt the need to hold transient life in words—there’s so much more of life that only words can convey—strongly enough to last me as long as I lived. The direction my mind took was a writer’s direction from the start, not a photographer’s, or a recorder’s.

I recently read an article about Alice Munro in The Guardian in which Chris Power suggests that Welty is “a particularly discernible influence” on Munro: “both writers are fascinated by the doubling of the world as it’s generally seen, and the stranger one it cloaks.”

In both writing and photography, Welty spoke of “trying to portray what you saw, and truthfully. Portray life, living people, as you saw them. And a camera could catch that fleeting moment, which is what a short story, in all its depth, tries to do.” This New York Times article includes some of the photographs she took during the Depression, of tomato packers, farmers, a nurse, a Sunday School class, and a blind weaver. My sister Bethie is especially interested in that last one, “The weaving woman and the blind bard in one image. She has fused together Penelope and Homer, but in a local, contemporary, humble context.”

Natasha Trethewey’s beautiful introduction to One Writer’s Beginnings inspired me to look up some of her work as well. I like what she says in the introduction about how “Whether or not we are writers, we tell a story to ourselves about our lives, the art of them—what gives meaning and purpose, and connects us to others.”

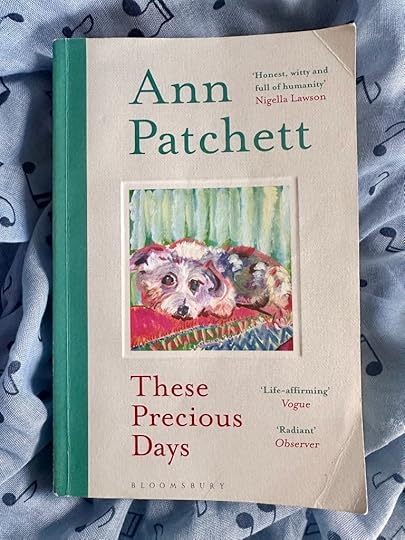

I’ve said One Writer’s Beginnings was a present from Bethie. Let me go back and tell the story of how she came to give me this wonderful book. If you’ve been reading my blog over the past year, you’ll probably remember that Bethie was living in Bonn, Germany, and I travelled there to visit her and her family (and the Beethoven statue, and the house where he was born, and Cologne Cathedral, and the ruined castle at Drachenfels, among other places). Last December, in a lovely bookstore in Bonn called Thalia, I bought a copy of Ann Patchett’s recent collection of essays, These Precious Days, to read on the flight home to Nova Scotia.

The bookstore, Thalia, is in the Marktplatz, inside a former theatre (Metropol)

This past summer, Bethie and her family moved from Germany to Mississippi, and when they stopped in Nova Scotia for a couple of weeks on their way to their new home, I gave her my copy of These Precious Days, thinking it would provide good company because many of the essays are about life in the South. (Someday, Bethie and I would love to visit Ann Patchett’s bookstore, Parnassus Books, in Nashville.) In the fall, when Bethie was looking for a book to send me, she settled on something by Welty, because she had read Patchett’s introduction to Welty’s Collected Stories, which is included in These Precious Days. She bought One Writer’s Beginnings for me and the Collected Stories for herself.

The blue scarf is from Beethoven’s House in Bonn

Patchett quotes Welty’s description of what it was like to discover Virginia Woolf, in 1930, “when I was young,” Welty says, “reading at my own will and as pleasure led me.” She read To the Lighthouse: “I fell upon the novel that once and forever opened the door of imaginative fiction for me, and read it cold, in all its wonder and magnitude.” Patchett encourages readers to reread Welty’s stories even if they’ve read them before, “because even as the text stays completely true to the writer’s intention, we readers never cease to change.” She praises Welty’s ability to “tell the truth of the landscape.” She says she could take the volume of stories apart “and type it up again, sentence by perfect sentence, to say, This is exactly what Mississippi is like.”

When Bethie first arrived in Mississippi, she was missing Beethoven, and the tradition of going for “coffee with Beethoven” in the Münsterplatz in Bonn. Maybe Welty is the new Beethoven? Or Elvis is the new Beethoven?? I’d like to see his birthplace in Tupelo. I haven’t been to Mississippi since I was fourteen, and I’m looking forward to making the trip, perhaps sometime in the coming year.

Bethie took this picture of me in May, the last time the two of us had coffee with Beethoven

I’d like to visit Eudora Welty’s house, at 1119 Pinehurst Street in Jackson, where she lived for almost eighty years. I was delighted to discover a reference to the house in the recent New Yorker profile of Kate DiCamillo, by Casey Cep. I had read this fascinating article when it was published in September—a rare example of me reading the New Yorker right away, rather than letting issues pile up for months before I start trying to catch up—but I hadn’t paid much attention to the part about Welty’s house because I hadn’t yet read One Writer’s Beginnings. Happily, my friend Lisa mentioned the article in November, and I read it again.

Here’s what Cep says about DiCamillo: “The closest thing to luxury in her house is two pairs of slippers: one under her desk, the other under her claw-foot tub. During a tour of Eudora Welty’s home, in Jackson, Mississippi, she was struck by the humanity of the novelist’s slippers, which were still waiting faithfully under her bathrobe long after her death. DiCamillo talked about them so much that her best childhood friend, Tracey Bailey, got her one pair, and her best writing friend, the author Ann Patchett, got her another.”

I’m still meditating on what Welty says about looking for the threads, “how to follow, how to connect.”

Some years ago, my daughter and I read Finding Serendipity, by Angelica Banks, in which the heroine, Tuesday McGillycuddy, follows a silver thread that leads her to the place stories come from. I like the idea of holding onto a thread that can help us return to the world of the imagination, if we’ve lost our way, or if the road we’re on turns out to be one that has “little intention of going anywhere.”

After we had read the book, I bought spools of silver thread for Bethie and my daughter and me. I keep mine on my desk, in a little dish filled with shells, stones, and sea glass, a letterpress S that a friend gave me years ago, and a ring I lost while swimming in the Atlantic Ocean when I was a child, which my Granny later found for me in a clump of seaweed after the tide had gone out.

I’m mixing metaphors by talking about threads and roads at the same time. But if these metaphors help us find our way to the next story, whether it’s the next book we read or the next book we write or the next story we tell each other or ourselves, then I’m in favour of keeping them both, along with the ring and the letter and the treasures from the sea.

After I had read One Writer’s Beginnings, I followed the thread, or the road, to Natasha Trethewey’s Native Guard: Poems, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2006. In “The Southern Crescent,” I read about her mother “leaving behind / the dirt roads of Mississippi” in 1959, “the film / of red dust around her ankles, the thin / whistle of wind through the floorboards / of the shotgun house, the very idea of home.” I read about her parents’ marriage in 1965 in “Miscegenation”:

A year later they moved to Canada, followed a route the same

as slaves, the train slicing the white glaze of winter, leaving Mississippi.

I read about her grief for her mother, who was murdered by her second husband. In “Myth,” Trethewey talks about “still trying / not to let go.” I thought of the Story Girl’s lament in The Golden Road for Paddy, the missing cat: “every night I dream that he has come home,” she says, “and when I wake up and find it’s only a dream it just breaks my heart.” Trethewey addresses her mother: “You’ll be dead again tomorrow, / but in dreams you live. So I try taking / you back into morning.”

When Trethewey was appointed poet laureate in 2012, she that when she learned of her mother’s death, “Strangely enough, that was the moment when I both felt that I would become a poet and then immediately afterward felt that I would not. I turned to poetry to make sense of what had happened. … It took me nearly 20 years to find the right language, to write poems that were successful enough to explain my own feelings to me and that might also be meaningful to others.”

Like Trethewey, DiCamillo has a deep knowledge of suffering and grief. Cep writes that “One gets the sense from the books that DiCamillo knows that ‘deeper dark’ better than most of us, but she has, in the past, avoided letting on just how well.” Only recently has she spoken of terrifying scenes from her childhood, images of her father that are “darkened by fear,” and of how she made peace “with the torment she hadn’t wanted but without which she worries she would not have become a writer.”

I’ve read some of DiCamillo’s books, including The Tale of Despereaux and The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane, but I hadn’t read her first novel, Because of Winn-Dixie, and I started it a few days ago after my friend Susan recommended it. I’d also like to read Great Joy, a Christmas picture book that comes highly recommended by my friend Lisa. Ann Patchett writes about DiCamillo as well as Welty in These Precious Days; her favourite of all DiCamillo’s books is The Magician’s Elephant. She writes that the books “had given me the means to look backwards. … The work of Kate DiCamillo had opened something in me, an ability to see and feel things that were very far from me now.”

Let’s go back to Welty and Montgomery for a moment, who both say that “nothing is ever really lost.” Patchett says that what DiCamillo’s books gave her was “the ability to walk through the door where everything I thought had been lost was in fact waiting for me. All of it. The trick was being brave enough to look.”

When I read about DiCamillo’s writing habits in the early years when she was also working for a wholesale book distributor, I thought again of Montgomery. DiCamillo used to “get up every day to write before her shift—first an hour early, then two hours early, at 4:30am, setting herself the task of producing two pages a day. She chose the predawn hours because neither the rest of the world nor her inner critic was awake yet. Sitting at a desk that her brother helped fashion out of a wooden fence from their back yard in Clermont, she wrote by candlelight and lamplight. She submitted short stories to every magazine for which she could find an address, including this one, and she kept submitting them long after others would have called it quits.”

In her autobiography, The Alpine Path, Montgomery describes one winter when she was teaching and felt too tired to write in the evenings. “So I religiously arose an hour earlier in the mornings for that purpose. For five months I got up at six o’clock and dressed by lamplight. The fires would not yet be on, of course, and the house would be very cold. But I would put on a heavy coat, sit on my feet to keep them from freezing and with fingers so cramped that I could scarcely hold the pen, I would write my ‘stunt’ for the day. Sometimes it would be a poem in which I would carol blithely of blue skies and rippling brooks and flowery meads! Then I would thaw out my hands, eat breakfast and go to school.”

I suspect there’s a connection between this habit Montgomery developed, of being able to write about warmth and sunshine while working in a cold house, and her ability to write cheerful stories while enduring periods of disappointment and unhappiness. She dealt with many losses in her life, beginning with the death of her mother in 1876, when Maud was just twenty-one months old. As Mary Henley Rubio says in Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings, Montgomery later wrote in her journal that “three simple words had fortified and sustained her throughout a troubled life.” One night when she was sleeping at her cousin Pensie Macneill’s house, Pensie’s mother came into the room to check on the girls, bent over them, and said the words “Dear little children.” Maud was pretending to be asleep, but she never forgot these kind words that were so unlike the things her “stern Grandfather” and “reserved Grandmother” said to her.

Trethewey, DiCamillo, and Montgomery have all spoken about the way difficult or traumatic experiences shaped their writing. By contrast, Welty says in One Writer’s Beginnings that she was “a writer who came of a sheltered life.” However, she says that “A sheltered life can be a daring life as well. For all serious daring starts from within.”

A couple of photos my husband took on his trip to Mississippi in November:

William Faulkner’s house, Rowan Oak

Well. I’ve written at length and I’m not at all sure I’ve found the “clear line” Welty talks about, but it feels important to follow the threads and make connections. To keep reading and talking about books, no matter how thick the “tangle” of the world we live in.

If you haven’t yet read One Writer’s Beginnings, I encourage you to seek it out. Read it for the description of Welty’s parents “whistling back and forth to each other up and down the stairwell,” when her father was upstairs “shaving in the bathroom and Mother downstairs was frying the bacon.” “Long before I wrote stories,” she says, “I listened for stories. Listening for them is something more acute than listening to them.” Read for the moment at which she was startled and disappointed “to find out that story books had been written by people, that books were not natural wonders, coming up of themselves like grass.” Read for the story of how as a child she made her way through the State Capitol to the library where the librarian allowed patrons to take out only two books at a time, and young Eudora knew the “bliss” of “the devouring wish to read,” and “The only fear was that of books coming to an end.”

I’ve dipped into Suzanne Marrs’s biography of Welty, and I’m intrigued by the range of responses to One Writer’s Beginnings: while many reviewers wrote of Welty as “shy and retiring,” saying (in the words of one critic) that she led “a relatively uneventful life,” later critics have drawn attention to the complexities of her life, beyond the image of her as the “happy child” of this memoir or as the “witty, elderly lady.” Perhaps her life was not as “sheltered” as she said it was. I’d like to read more.

I’m immersed in Welty’s essays now, and I was delighted to find that the first essay in The Eye of the Story is called “The Radiance of Jane Austen”: “The sheer velocity of the novels, scene to scene, conversation to conversation, tears to laughter, concert to picnic to dance, is something equivalent to a pulsebeat. The clamorous griefs and joys are all giving voice to the tireless relish of life. The novels’ vitality is irresistible for us. … Everybody doing everything together—what mastery she has over the scene, the family scene!”

I’m interested in reading more books by Mississippi writers, starting with Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing. I’d also like to read more by Kiese Laymon, whom I quoted in last week’s post—“READ when you’re angry”—and whose essay on gas station restaurants I enjoyed reading earlier this week. He says, “I’d never really thought about the fact that my favorite restaurants, as a child, as a teenager, as an adult returning to Mississippi, nearly all served gas. And I never, ever thought of them as gas stations that served food.” I’d be glad to hear other recommendations.

Many thanks to my dear sister Bethie for the gift of One Writer’s Beginnings. She told me recently that she had just finished reading Elizabeth Hay’s Late Nights on Air, “which I loved,” she said. Hay’s novel won the Scotiabank Giller Prize in 2007. “I guess it took me a while to get to it,” Bethie says, “but it somehow came into my hands at just the right moment. Having just moved to the deep South, I found Hay’s writing about the far North extraordinarily refreshing. Here’s to all the books waiting on shelves, in piles (or boxes), and on lists!”

I too loved Late Nights on Air, and Hay’s memoir All Things Consoled. I haven’t yet read her novel Garbo Laughs, which was honoured with a Project Bookmark Canada Bookmark in Ottawa, Ontario (you can see photos of the Bookmark plaque here) and since I’m a long-time supporter of Project Bookmark, I’ll follow the thread and add the novel to my list.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!