Power and The Presidency

These are a series of essays based on lectures given at Dartmouth. David McCullough introduces us:

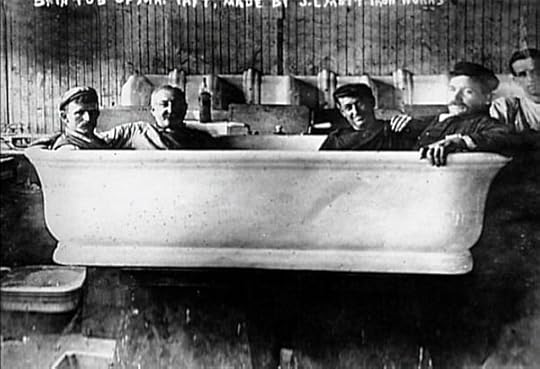

In a wonderful old photograph, the three workmen who did the installation sit together quite comfortably in Taft’s giant tub.

Is this the photo he’s talking about?

Doris Kearns Goodwin on FDR’s power of persuasion:

At the Democratic Convention in 1936, Roosevelt answered the attacks in dramatic form. He admitted he had not kept his pledge. He admitted that he had made some mistakes in the early years. But then he quoted the famous line: “Better,” he said, “the occasional faults of a government guided by a spirit of charity and compassion than the constant omissions of a government frozen in the ice of its own indifference.” As he was making his way up to the podium to that “Rendezvous with Destiny” speech, leaning on the arms of his son and a Secret Service agent, his braces locked in place to make it seem as if he could walk (he really could not on his own power), he reached over to shake the hand of a poet. He immediately lost his balance and fell to the floor, his braces unlocked, his speech sprawled about him. He said to the people around him, “Get me up in shape.” They dusted him off, picked him up almost like a rag doll, put his braces back in place, and helped him up to the podium. He then somehow managed to deliver that extraordinary speech.

There weren’t that many fireside chats:

He delivered only thirty fireside chats in his entire twelve years as president, which meant only two or three a year. He understood something our modern presidents do not: that less is more, and that if you go before the public only when you have something dramatic to say, something they need to hear, they will listen. Indeed, over 80 percent of the adult radio audience consistently listened to his fireside chats.

FDR truly swayed public opinion towards what he wanted:

And somehow, through his ability to communicate, he educated and molded public opinion. At the start of this process, the people were wholly against the idea of any involvement with Britain. By the time the debate finished in the Congress and the Lend-Lease Act was passed, the majority opinion in the country was for the lend-lease program. That is what presidential leadership should and must be about. Not reflecting public opinion polls, taking focus groups to figure out what the people are thinking at that moment, and then simply telling them what they’re thinking, but rather moving the nation forward to where you believe its collective energy needs to go.

Life in the FDR White House during WWII:

He became a part of an intimate circle of friends who were also living in the family quarters of the White House during the war, including Franklin’s secretary, Missy Lehand, who had started working for him in 1920, loved him the rest of her life, and was his hostess when Eleanor was on the road; Franklin’s closest adviser, Harry Hopkins, who came one night for dinner, slept over, and didn’t leave until the war was coming to an end; Eleanor’s closest friend, a former reporter named Lorena Hickock; and a beautiful princess from Norway, in exile in America during the war, who visited on the weekends.

Michael Beschloss on Eisenhower:

To hold down the arms race as much as possible, he worked out a wonderful tacit agreement with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev. Khrushchev wanted to build up his economy. He didn’t want to spend a lot of money on the Soviet military because he wanted to start feeding people and recover from the devastation of World War II. But he knew that to cover this he would have to give speeches in public that said quite the opposite. So Khrushchev would deliver himself of such memorable lines as, “We Soviets are cranking out missiles like sausages, and we will bury you because our defense structure is pulling ahead of the United States.” Eisenhower dealt with this much as an adult deals with a small boy who is lightly punching him in the stomach. He figured that leaving Khrushchev’s boasts unanswered was a pretty small price to pay if it meant that Khrushchev would not spend much money building up his military. The result was that the arms race was about as slow during the 1950s as it could have been, and Eisenhower was well on the way to creating an atmosphere of communication. Had the U-2 not fallen down in i960 and had the presidential campaign taken place in a more peaceful atmosphere, I think you would have seen John Kennedy and Richard Nixon competing on the basis of who could increase the opening to the Soviets that Eisenhower had created.

Eisenhower pursued almost an opposite strategy to Reagan re: the USSR.

On one of the tapes LBJ made of his private conversations as president, you hear Johnson in 1964. He knows that the key to getting his civil rights bill passed will be Everett Dirksen of Illinois, Republican leader of the Senate. He calls Dirksen, whom he’s known for twenty years, and essentially says, “Ev, I know you have some doubts about this bill, but if you decide to support it, a hundred years from now every American schoolchild will know two names—Abraham Lincoln and Everett Dirksen.” Dirksen liked the sound of that.

I don’t think that worked. I’ll quiz the next American schoolchild I encounter.

On JFK:

What’s more, he had been seeking the presidency for so long that he had only vague instincts about where he wanted to take the country. He did want to do something in civil rights. In the i960 campaign, he promised to end discrimination “with the stroke of a pen.” On health care, education, the minimum wage, and other social issues, he was a mainstream Democrat. He hoped to get the country through eight years without a nuclear holocaust and to improve things with the Soviets, if possible. He wanted a nuclear test ban treaty.

Bay of Pigs:

People at the time often said Eisenhower was responsible for the Bay of Pigs, since it was Eisenhower’s plan to take Cuba back from Castro. I think that has a hard time surviving scrutiny. Eisenhower would not necessarily have approved the invasion’s going forward, and he would not necessarily have run it the same way. His son once asked him, “Is there a possibility that if you had been president, the Bay of Pigs would have happened?” Ike reminded him of Normandy and said, “I don’t run no bad invasions.”

Then Robert Caro comes to the plate with some classics:

Trying to understand why this relationship developed, I asked some of Roosevelt’s assistants. One of them, Jim Rowe, said to me, ‘You have to understand: Franklin Roosevelt was a political genius. When he talked about politics, he was talking at a level at which very few people could follow him and understand what he was really saying. But from the first time that Roosevelt talked to Lyndon Johnson, he saw that Johnson understood everything]! ^ was talking about.”

This young congressman may have been unsophisticated about some things, but about politics—about power—he was sophisticated enough at that early age to understand one of the great masters. Roosevelt was so impressed, in fact, that once he said to Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, “That’s the kind of uninhibited young politician I might have been—if only I hadn’t gone to Harvard.” Roosevelt made a prediction, also to Ickes. He said, ‘You know, in the next generation or two, the balance of power in the United States is going to shift to the South and West, and this kid, Lyndon Johnson, could be the first southern president.”

Hill Country:

It was also hard for me to understand the terrible poverty in the Hill Country. There was no money in Johnson City. One of Lyndon’s best friends once carried a dozen eggs to Marble Falls, 22 miles over the hills. He had to ride very slowly so they wouldn’t break; he carried them in a box in front of him. The ride took all day. And for those eggs he received one dime.

Hill Country women:

asked these women—elderly now—what life had been like without electricity. They would say, “Well, you’re a city boy. You don’t know how heavy a bucket of water is, do you?” The wells were now unused and covered with boards, but they would push the boards aside. They’d get out an old bucket, often with the rope still attached, and they’d drop it down in the well and say, “Now, pull it up.” And of course it was very heavy. They would show me how they put the rope over the windlass and then over their shoulders. They would throw the whole weight of their bodies into it, pulling it step by step while leaning so far that they were almost horizontal. And these farm wives had yokes like cattle yokes so they could carry two buckets ofwateratatime. They would say, “Do you see how round-shouldered I am? Do you see how bent I am?” Now in fact I had noticed that these women, who were in their sixties or seventies, did seem more stooped than city women of the same age, but I hadn’t understood why. One woman said to me, “I swore I wouldn’t be bent like my mother, and then I got married, and the babies came, and I had to start bringing in the water, and I knew I would look exactly like my mother.”

LBJ effectively nagged FDR until he got a dam built and then transmission lines extended that would electrify Hill Country:

This one man had changed the lives of 200,000 people. He brought them into the twentieth century. I understood what Tommy Corcoran meant when he said, “That kid was the best congressman for a district that ever was.”

Ben Bradlee on Nixon:

When he was detached, Nixon could see with great subtlety the implication of actions. The story about Chicago mayor Richard Daley delivering enough graveyard votes for Kennedy to win one of the narrowest victories in the history of presidential politics is well known. Some say that Nixon made a very statesmanlike, unselfish decision in not protesting voting irregularities. He felt, they suggest, that it could weaken the country to have no one clearly in charge while the dispute went on. But as someone who covered the story closely—I was the reporter who quoted Daley’s remark to JFK on election night: “With a little luck and the help of a few close friends, we’re gonna win. We’re gonna take Illinois”—I am not so sure of Nixon’s altruism. What actually happened was this: Nixon sent William P. Rogers, who would later become his attorney general, to check on the situation. Rogers reported back that however many votes were cast illegally by Democrats in Chicago and Cook County, just as many were probably cast illegally by Republicans in downstate Illinois. I am almost certain that Nixon would have found it irresistible to protest the illegal votes had it not been for the fact that his own party might have been doing the same thing. He made a political decision: The risk was too great. He certainly had the power to protest, but for not entirely statesmanlike reasons chose not to use it.

Edmund Morris in his lecture gives some of the clearest takes on Reagan I’ve seen him deliver:

In the last weeks of 1988, toward the end of his presidency, he let me spend two complete days with him. I dogged his footsteps from the moment he stepped out of the elevator in the morning till the moment he went back upstairs. Within hours I was a basket case, simply because I discovered that to be a president, even just to stand behind him and watch him deal with everything that comes toward him, is to be constantly besieged by supplications, emotional challenges, problems, catastrophes, whines. For example, that first morning I’m waiting outside the elevator in the White House with his personal aide, Jim Kuhn. The doors open, out comes Ronald Reagan giving off waves of cologne, looking as usual like a million bucks, and Jim says to him, “Well, Mr. President, your first appointment this morning is going to be a Louisiana state trooper. You’re going to be meeting him as we go through the Conservatory en route to the Oval Office. This guy had his eyes shot out in the course of duty a year ago. He’s here to receive an award from you and get photographed, and he’s brought his wife and his daughter. You’ll have to spend a few minutes with him, just a grip-and-grin, and then we’re going on to your senior staff meeting.” So around the corner we go, and I’m following behind Reagan’s well-tailored back, and there is this state trooper, eyes shot out, aware of the fact that the president is coming—he could hear our footsteps. And there’s his wife, coruscating with happiness. It’s the biggest moment of their lives. There, too, is their little girl. Reagan walks up, introduces himself to the trooper, gives him the double handshake—the hand over the hand, the magic touch of flesh—and expertly turns him so the guy understands they are going to be photographed. The photograph is taken, a nice word or two is exchanged with his wife. It lasted about thirty-five seconds. On to the Oval Office. By the way, Reagan said to me as we walked along, ‘You know the biblical saying about an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth? I sure would like to get both eyes of the bastard that shot that policeman.” In other words, he was as moved as I was. But he had magnificently concealed it. A president has to deal with this kind of thing all day, every day, for four or eight years. He therefore has to be the kind of person who is expert at controlling emotion, at not showing too much of it—containing himself; otherwise, he is going to be sucked dry in no time at all and lose his ability to function in public.

(Also an origin story to why he wrote about Theodore Roosevelt:)

Theodore Roosevelt was also a man of overwhelming force—a cutter-down of trees in the metaphorical sense. He was famously aggressive. There was nothing he loved more than to decimate wildlife. I first became aware of him as a small boy in Kenya, when the city of Nairobi, where I was born, published its civic history. The book contained a photograph of this American president with a pith helmet and mustache and clicking teeth and spectacles. He had come to Kenya from the White House in 1910 and proceeded to shoot every living thing in the landscape. I remember as a ten-year-old boy looking at this picture of this man and, as small boys do, saying to myself, “He looks as though he is fun. I’d like to spend time with that guy.” I was conscious even as a child not only of the sweetness of his personality but of this feeling of force that a smudgy old photograph could not obscure.

Reagan’s voice:

Now, Reagan’s voice, which was a large part of Reagan’s power, was indeed beautiful. Even in his teenage years it was unusual, a light, very fluid baritone, quick and silvery. It had a fuzzy husk to it, rather like peach fuzz. And there was something sensually appealing about it—so much so that people got physical pleasure out of listening to Reagan talk.

…

Dutch Reagan was an extremely successful sportscaster. His mellifluous voice beamed out over Iowa and Illinois and the central states, first from WOC-Davenport and then from WHO-Des Moines. It beamed to such a beguiling extent that Hugh Sidey, the presidential correspondent of Life magazine, once told me, ‘You know, I was a Dust Bowl brat in the early 1930s, living in Iowa. I used to hear Dutch Reagan’s voice coming through our loudspeaker, and I don’t remember anything he said, but that voice persuaded me that although life was terrible at the moment, somehow things were going to get better.” He said, “I cannot describe the quality of the voice; it just filled me with optimism.” And we saw this come to pass when Reagan eventually became president and filled us almost overnight with a sense of well-being and purposeful-ness.

A revealing visit to the ranch:

It perplexed me for at least a year until I was sitting with Reagan on the patio of his beloved Rancho del Cielo, “Ranch in the Sky,” in southern California. He had given me a tour of this surpassingly ordinary little house, a cabin that he’d put together practically with his own hands. It had phony tile flooring, an ugly ceiling, horse pictures hanging crooked, a Louis L’Amour novel by his bedside. He takes me out onto the patio and we sit down at a leather table pocked with food stains, beneath a flypaper with dead flies on it, looking out over the valley, and he says, “Isn’t it beautiful?” and I said, ‘Yes, Mr. President, it is very nice.” But you know, it was not naturally beautiful. It was a long, manicured—that’s the only word I can think of—manicured valley, open in the central part, but rising on both sides to a ridge that overlooked the Pacific. And all the madrona trees and live oaks that encircled this valley had been manicured to such an extent—I’m not talking topiary now, I’m just talking about trimming limbs and taking off dead leaves and undergrowth—had been pruned to such an extent that it was not quite real. It looked like a Grant Wood landscape. It was too clean.

The impossibility of changing Reagan’s mind:

Michael Deaver told me that once in 1973, when Reagan was still governor, they were talking to him across a table about the enforced resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew, who had had to step down for taking bribes and corruption in office. Reagan was saying, ‘You know, it’s really tough what they did to Agnew. I always liked that guy. It was very unfair what happened to him.” And Deaver said, “Governor, he took money in office. The guy was a sleazebag. He had to be thrown out.” Reagan was playing with a heavy bunch of keys when Deaver said this. He hauled back and threw the keys smack into Deaver’s chest—koodoomp! He was angry at being confronted with evidence that conflicted with his sentiments.

David Maraniss on Clinton:

And yet when you look at what he used his power for—at his achievements, particularly in domestic policy—I think a strong argument can be made that they are largely moderate Republican programs. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the balanced budget, and welfare reform are the central programs that have passed, largely through a coalition of President Clinton and the Republicans in Congress. That’s where his power went.