Bad Advice Wednesday: Make Like Shakespeare, or at Least Spalding Gray

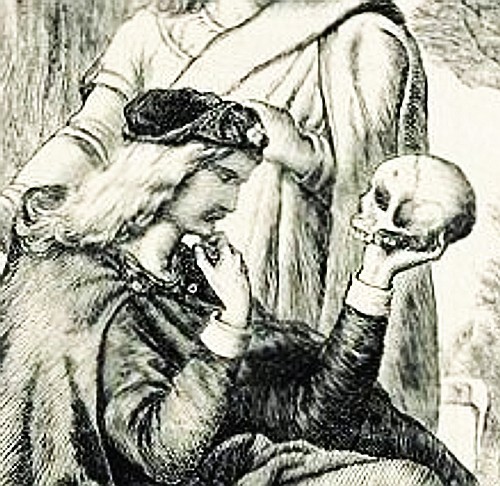

Alas, poor Dave! I knew him, Horatio.

.

Write a monologue.

.

Yes, that’s it. Today’s bad advice is to write a monologue. This is not just for writers, but for everyone. Though if you’re a writer, it’s a magical exercise. A monologue is one character (or even just a regular person) speaking directly to an audience. It’s different from a soliloquy, which is a character speaking to himself, audience be damned, though they’re listening in. It’s how playwrights used to get a character’s thoughts out to the world (filmmakers use flashbacks). A dramatic monologue? That’s a character speaking to someone else who’s usually sitting or standing uncomfortably nearby onstage. An apostrophe is a kind of dramatic monologue, but spoken to someone who’s not there, usually dead. An aside is spoken to an audience, out of earshot, so to speak, from other characters. I used to love George Burns’s asides to the camera on the Burns and Allen TV show, many years gone. An interior dialogue is a nice way to say it: talking to yourself. And then there’s the narrative monologue, telling a story. This is the stuff of stand-up comedy on the one hand, the greatness of Spalding Gray on the other.

Why, you may ask, should you write a monologue? Oh, go ahead, resist. I have no investment in your becoming a better writer, a better person, a better soul, almost a saint. Why, if it were up to me, only I would be allowed to write monologues. Because they are that cool.

So perhaps this is a soliloquy. But if anyone out there is listening, well, now, that’s dramatic, right. (I wake this morning with my belly arumble, my night having been filled with all things undone, or things done poorly, my day stretched too short before me, another night ahead!)

The exercise is as follows, adjusted for the various arts:

Essayist: You are already engaged in monologue, let’s face it. But if it’s a soliloquy, try aiming it outward—think of that one person sitting awkwardly onstage with you as you speak: who would it be? And for more drama, make it an apostrophe: to whom do you wish you could speak your piece without interruption? Well, do so. And be sure to stand up from your desk and actually say your essay, every word.

Memoirist: You, too. Aim that voice outward. But more than that, use monologue to get a handle on what your work is really about. Your bowling career, sure, but what’s the big picture? I mean, what’s it all about, being a bowler but also a human alive in the 21st century, or any century, come to think of it? The monologue gives you a chance and rather forces you to say what the greater piece is doing or should be doing, gives you a chance to get to the aboutness of your pages. Don’t tell stories in this monologue–that’s for the memoir itself. In this monologue, explain what your stories mean. Explain yourself. Another magical thing for the memoirist to do is to write monologues for all those friends and family in your piece. Not to use, because of course that wouldn’t be right, but to learn from–let them speak for themselves–and to hear voices. This is helpful for those who are dead or uncooperative, but also for those you can later phone or visit: You’re going to listen very carefully, now that you’ve spoken for them: what did you get right? What did you get wrong?

Juggler: Always with the banter, aren’t you. Try this: Make yourself a character, and tell the audience about yourself, all with pins and flames in the air, also a couple of oranges.

Novelist: Find every single character in your book and write a monologue for each. Not necessarily for the book, but to really hear who each person is, and what they’re thinking about. You’ll have a rounder, smarter, more vivid cast. And each character down to the lowliest passerby will have a voice their own. Stand your character’s mother up there, and let her go. It might surprise you (and your character) to realize that she isn’t actually thinking about the character’s plight much at all, but about her hairdresser’s affair with that physicist from the university, the man who gave a talk on prions and got Mom interested in going back to school, which, secretly, she’s applied for: Harvard.

Short Story writer: with fewer characters in tow and likely a shorter time frame, it pays to know what everyone’s thinking, down to the details. And the monologues you write now will improve the dialogue you write later: each character, her own problems, her own focus, her own voice.

Poets: You are already doing this, in one form or another. Discern which form. And then try the others. And, as for all your writers, read the stuff out loud and aimed at a person. Ideal if you can get that actual person to sit there while you do it.

Teachers (that’s all of us): This is a really great exercise for classes, students of all ages. You get the group to write monologues at home, or in class, and then–this is important–they perform them. For younger writers, you can bring a stack of index cards in different colors. On blue, say, the kids write a name. On red, a profession. On yellow, a place. On orange, an era. On purple, a problem. On green, an object. You collect all the cards, shuffle them, and pass them around color by color. And then the kids retreat to the various corners of their underfunded library or school and write. An astronaut named Bumidji Collins whose wife just left him, 1995, the South Pole. He’s got an electric guitar. After a half hour or so, all these new inventions, people who never existed before the index cards, come back and declaim. It’s really, really wonderful stuff, with even young kids able to find real depth, often sorrow, almost always comedy.

For college kids, you just send them home with instructions to write a monologue by one of their minor characters, and again, elicit performances. I actually make them stand up and speak to someone else (to make it dramatic), and give notes on the acting, get them to try again, really act. Then go back and revise.

Later, lo and behold, you find snatches and whole speeches from the exercise in the mouths of characters in their stories.

And I use the technique myself, when I’m trying to understand a character. In the new book, I’ve got a bad guy who’s just really bad and I was having trouble giving him motivations, trouble getting where all his manipulative, greedy, violent impulses came from. He surprised me by talking about money. That’s what he talked about. I hadn’t planned it. He talked in his monologue about money like the rest of us might talk about sex or food or love. And it really helped as I went forward with his scenes, a guy sizing up pockets as he went about his day.

A young woman I had written in a short story–minor character, love interest of the narrator–surprised me in monologue (aimed at her best friend, who never made an appearance in the story at all) by talking very passionately about him. And here he (and the story) had thought the relationship almost over, a disaster. So then I had her talk some more. He required too much coddling, too much reassurance. And he was too passive. His neediness excited her resistance, his passivity made her listless, though she loved him. And in her monologue she remembered the bed of much better lover than my protagonist, remembered an earlier, angrier boyfriend, found protagonist altogether much more wonderful, just frustrating, even a little impotent. And at the end of all this the friend said, “Buy him flowers.” Which I thought at first was a throwaway, a joke, something my subconscious mind pulled for laughs. I cut it.

But then in an advanced draft of the story, I surprised myself by trying a new opening: the young woman given our protagonist flowers, a huge bouquet she’s picked from the fields. So, okay, now that was how the story started. She’s overcome her aversion to coddling anybody and brought him flowers, kind of feminizing, of course, the opposite of what some might think he needs, but, no: the gesture changes him in some ineffable way, and the change powers the story (it had lacked an engine), a story that’s not about their relationship at all.

In life, you can use this exercise to parse problems. Write monologues for the people who are bugging you, for example. Or write your own monologue, holding their skulls in your hands.

(I’ll talk about Spalding Gray at length in a future post–he’s the tragic hero of the narrative monologue.)

(And please, Like Bill and Dave’s–that button up there in the upper right hand corner? Like? It produces endorphins in your brain and makes you feel as if you were in love–go ahead, try it! And speaking of endorphins, follow me on Twitter: @billroorbach)