Written By Men For Men

“To be heard, you must speak the language of the one you want to listen.”

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

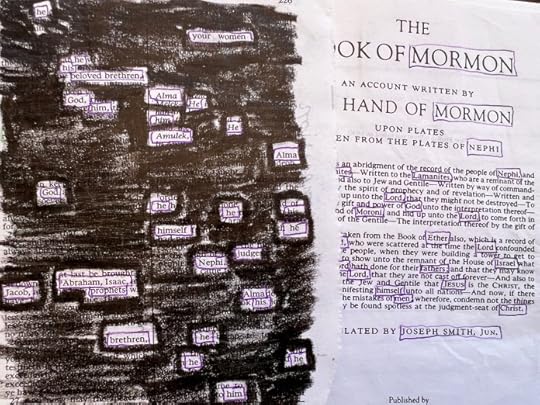

The book I have read more than any other book is ripped apart and hidden in my bathroom cabinet. I have more copies of this book than any other book I own – it keeps appearing in my closet, on my bookshelves, tucked beneath my bed as I organize and clean my house for the changing season. But I have not read this book in years, and recently, in the name of healing poetry, I have started mutilating it.

The Book of Mormon is the book I read more times and have more copies of than any other book. My life was built around Book of Mormon stories and characters; my earliest memories of reading words were stumbling over “therefore” and “Lamanites” as I read the verses each night with my family. My grandparents celebrated their grandchildren who finished the Book of Mormon each year by taking us to the Golden Corral; a metaphor for “feasting on the words of Christ.” And it took me years to recognize that this book was not written for me.

Joseph Smith said: “the Book of Mormon was the most correct book of any book on earth.” So, I read it constantly. Each of my copies are colorfully marked up with words like “compassion” and “love” written in the margins. I assumed the book was for everyone and I found what I was looking for in a book full of men, written by men for their sons and brothers: I mined stories of love and compassion in this book about men and their wars.

And then I read the first three pages of the Dance of the Dissident Daughter and sobbed on a bench at an ice-skating rink. She. Her. Womb. Feminine. Goddess. Language matters. And Sue Monk Kidd was writing my wounds and despair into language that hugged me and held me rather than pushed me out and horrified me.

In Old English, the word mann meant “thinking one” and included all bodies, evidenced in the words: human, mankind, and woman. But language is fluid and changing (“awful” used to mean “worthy of awe”) and the word “man” now means “an adult male human being.” That is what it means to me. Every time I read it. And I realize: the Book of Mormon was always intended for men (males), not me.

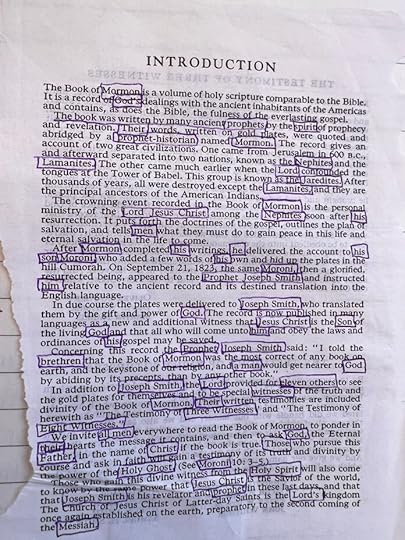

The Introduction to the Book of Mormon (written in 1981, when the men who wrote it spoke modern American English) states that they “invite all men everywhere to read the Book of Mormon.” They suggest that it tells “men what they must do to gain peace.” And they quote Joseph Smith, who “told the brethren that the Book of Mormon was the most correct of any book . . . and a man would get nearer to God by abiding by its precepts . . .” Joseph Smith never told everyone that the Book of Mormon was correct for anyone, only his brethren.

This makes sense to me, and once I read The Dance of the Dissident Daughter, I could not stop reading texts that included me. I feasted on Braiding Sweetgrass, Women Who Run With the Wolves, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, This Here Flesh, The Power of Kindness, Tattoos on the Heart, The Power of Ritual, etc. and felt what it was to have scripture written for me – to hear and see a God that isn’t just for men but for everyone.

I have read the Book of Mormon countless times and I am grateful for the language and songs that built my history, the ones that taught me about transformation in the waters of Mormon and the anti-Nephi-Lehi’s who didn’t fear death and the vision of a tree. I appreciate the study and love and dissecting and rejecting I learned from these words of men. I’m grateful for the parallels between Korihor the Anti-Christ and Alma the Younger – one privileged and the other condemned; one allowed to face his shadow, the other punished and killed by cruelty before he could change because he was not a son of a prophet. So, you see, I have learned to see myself in “him.”

However, I do not read this book anymore; we should believe Joseph Smith and the other men when they say their messages are for their brethren. I always felt I didn’t exist in the language of their stories – now I understand why that matters: because there are words and language and stories where I do exist. Words that are written for everyone.

“Language is our gift and our responsibility.”

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass