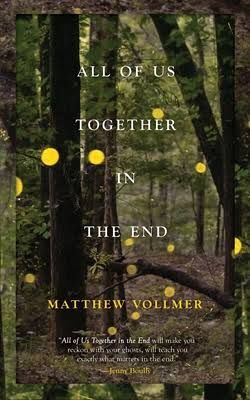

All of Us Together in the End, by Matthew Vollmer

This is such a lovely book that I read it in a day, but took weeks to process it before I was ready to write a blog post about it.

Like Stillwater by Darcie Friesen Hossack, which I reviewed for Spectrum magazine, All of Us Together in the End falls into the tiny, but always fascinating-to-me, category of books about Adventists that are not specifically written by or for Adventists. That alone would have been enough to hook me, as would Sari Fordham’s beautiful review of the book, also in Spectrum. (I should note that Fordham’s own memoir, Wait for God to Notice, is another book in this rarified category which I loved and wrote about here.)

However, what really made All of Us Together in the End a must-read-now book for me was the premise that drives this memoir. Matthew Vollmer, a former Adventist from a family with, to put it mildly, impeccable SDA credentials (OK, his aunt is married to Ted Wilson! Though I’m more impressed that his uncle was in the Wedgewood Trio, and also, I think, knew my uncle, because that’s Adventism for you), writes about the months following his mother’s death. Matthew’s father, who lovingly cared for his wife during her long decline with dementia, begins seeing mysterious lights in the trees near his home at night. Both Matthew and his father become fascinated with these lights, which have no logical explanation.

Of course, virtually everyone Matthew Vollmer tells about the lights has the same explanation, regardless of the person’s spiritual tradition or belief system: these lights, appearing so soon after the death of a beloved wife and mother, must be a message from her from the afterlife, letting her family know that in some way she is nearby and still with them. The only people not likely to accept this explanation would be a hardcore atheist who denies any supernatural phenomena — or a committed Seventh-day Adventist, who has spent their whole life believing that “the dead know not anything” and that any communication from “beyond” is a delusion at best, a demonic trap at worst.

This is such a very specific but, to me, very recognizable phenomenon, that I knew I had to read the book. One of my key family origin stories is of the night the Caribou was torpedoed and sank in 1942 and my great-grandfather, a crew member, was drowned. The story goes that the next morning my late aunt, his granddaughter (about 12 at the time), said she had seen Grandfather sitting by her bed during the night, even though she knew he was at sea. The family only learned of the ship’s sinking later. Anyone else in Newfoundland would call that a “token” — a visit from a family member’s spirit at the moment of their death far away — but everyone in our family were staunch Seventh-day Adventists; they had no explanation for this experience that would fit their worldview.

This is the cognitive dissonance that Matthew Vollmer writes about with such curiosity, openness, and humour. Of course, this book is about more than the mysterious lights. It’s about grief: about losing a parent and watching the other parent go through and then move on from that loss; it’s specifically about grief during Covid times, which reminded me of another great memoir I read this year, Nicole Chung’s A Living Remedy.

The book is also about the journey of losing your childhood faith while retaining the connection to loved ones who still hold that faith. For some people, this is a much more fraught and angst-ridden experience than Vollmer depicts it as in this book. He doesn’t get into a whole lot of analysis about his own “deconstruction,” and it seems, happily for him, that even the most deeply-Adventist members of his immediate and extended family are glad to maintain ties with those who are no longer in the church. This is another thing that fits well with my own experience (coming from a large Adventist family in which very few members are still actively involved in the church) but I realize that’s not everyone’s experience and for some people, it’s impossible to maintain those ties because there’s too much hurt and judgement.

If someone’s family has treated them harshly after they left their faith, and they write a memoir reflecting hurt and anger about that, that’s valid and I want to read it. But there was a kind of joy and relief in reading about a family that can still enjoy a meal of haystacks together when one member has left the church altogether and others are still active, not just in the pews but in leadership roles, since that’s what my own family is like.

That’s not to say that there’s no bittersweetness in this exploration of family, faith, and the loss of faith — even beyond the bittersweetness of loss and grief. Maybe it just comes from having an Adventist or perhaps a generally religious background, but as soon as I saw the title of the book I knew the context of the conversation in which it appears — in a flashback scene when Matthew Vollmer’s mother is still well and able to communicate, he asks her how she really feels about his having left the church, and she says, as many Christian mothers would, “I just want all of us to be together in the end.”

In the end, that is, after this life. In an afterlife that, to someone like Matthew’s mother (and perhaps to me?) has far less to do with mysterious flickering lights offering a comforting sense of presence, and more to do with the song Side by Side that we’ve all sung at a hundred summer camps and youth meetings:

Meet me in heaven, we’ll join hands together

Meet me at the Savior’s side

Meet me in heaven, we’ll sing songs together

Brothers and sisters, I’ll be there….

Pray that we all will be there.

This is a tender, thoughtful, beautifully written memoir, and could not have been more specifically targeted to my reading tastes if it had been personally addressed to me. But I think some of you might like it too.