Marcus Aurelius as Disciple of Epictetus

Epictetus was the most important Stoic philosopher of the Roman Imperial period, and perhaps even the most influential philosophy teacher in Roman history. We can see that he had considerable influence over Marcus Aurelius but the relationship between them probably requires some explanation.

Ancient Stoicism took different forms. The rhetorician Athenaeus, who lived around the same time as Marcus, claimed that the Stoic school had divided into three branches. These consisted of the followers of the three last scholarchs, or heads, of the school: Diogenes of Babylon, Antipater of Tarsus, and Panaetius of Rhodes. Although it’s difficult to know exactly what the differences were, it seems likely that the Stoicism of Panaetius was more philosophically eclectic in nature, drawing more upon aspects of Platonism and Aristotelianism.

Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Epictetus never mentions the “Middle Stoicism” of Panaetius and seems instead to hark back to an older form of the philosophy, more aligned with Cynicism. The only one of the three scholarchs above he mentions is Antipater, so it’s possible he saw himself as following the “Antipatrist” branch of Stoicism. Marcus aligned himself mainly with Epictetus, and perhaps assumed he was part of the same branch of Stoicism.

It is fair to say that the essential substance of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations comes from Epictetus. — Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, 195

The Men who Knew Epictetus

The Men who Knew EpictetusMarcus was only about fourteen years old when Epictetus died. He’d probably never left Rome and it seems virtually certain that the two never ever met in person. Epictetus had previously lived and taught philosophy in Rome but left around 93 AD when the Emperor Domitian banished philosophers, nearly three decades before Marcus Aurelius was born. He set up a Stoic school in Nicopolis in Greece, where he remained for the rest of his life. However, their lives overlapped and Marcus surrounded himself with philosophers, particularly Stoics. Some of the older men he knew had doubtless studied with Epictetus in person.

The Emperor Hadrian was a passionate hellenophile and associated with many philosophers. Though far from a Stoic himself, he was reputedly a personal friend of Epictetus. Marcus was close to Hadrian, who chose him to succeed Antoninus, his immediate heir. So it’s quite possible Marcus first heard of Epictetus from Hadrian and other members of his court. However, Marcus’ natural mother was another hellenophile and there’s a hint she was friends with Junius Rusticus, whom we’ll return to below. It’s vaguely possible she also had some familiarity with Epictetus or his students. Marcus mentions that Rusticus wrote an admirable letter consoling his mother. Rusticus was closer in age to Domitia Lucilla than to Marcus. It’s therefore possible that he was already a family friend prior to becoming Marcus’ tutor in philosophy, and it seems likely that he was an admirer, and perhaps former student, of Epictetus.

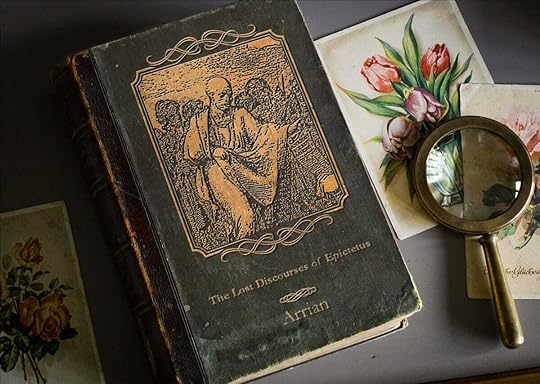

The Discourses and Handbook of Epictetus were not actually written by him but are edited notes made at his school by a student called Arrian of Nicomedia. Arrian was himself an exceptional man. He was reputedly, like Epictetus, a personal friend of Hadrian. Hadrian appointed him to the Senate and then made him suffect consul around 132 AD. He was later made governor of Cappadocia, for six years, where he became an accomplished military commander. Late in life, around 145 AD, he retired to Athens to serve as archon there, now under the emperor Antoninus. He was a prolific writer, highly esteemed as an intellectual, as well as being one of the most senior statesmen and military commanders in the empire. His relationship with Epictetus was compared to that of Xenophon with Socrates.

Arrian probably died not long after Marcus was acclaimed emperor in 161 AD, but it’s quite possible Marcus could have met him if Arrian ever visited Rome. He must certainly have known of him as Arrian held important roles during the reign of Antoninus, in the administration of which Marcus was effectively second-in-command. Arrian almost certainly knew Antoninus personally and probably also knew many other men in Marcus’ acquaintance.

Marcus reads EpictetusMarcus’ main Stoic tutor was Junius Rusticus. In The Meditations, Marcus stated that Rusticus gave him a copy of notes (hypomnemata) of Epictetus’ lectures. This could be taken to refer to personal notes taken down by Rusticus. However, Marcus quotes from Arrian’s edition of The Discourses several times so it’s generally assumed those were the “notes” of Epictetus’ lectures to which he referred. Of course, it’s also possible that Marcus possessed both The Discourses noted down by Arrian and also notes taken by Epictetus’ other students. Rusticus could easily have attended Epictetus’ school himself if he had travelled to Greece, and provided Marcus with notes on his lectures. He certainly seems to have encouraged Marcus to study Epictetus’ branch of Stoicism.

Marcus clearly felt that getting his hands on a copy of the Discourses was one of the key events in his life.

However, one later Roman source indicates that Rusticus served alongside Arrian in the Roman was against the Alani, toward the end of Hadrian’s rule. So it seems quite possible that Rusticus met Arrian, who provided him with a copy of The Discourses in person.

To make the acquaintance of the Memoirs of Epictetus, which he supplied me with out of his own library. — Meditations, 1.7

Marcus clearly felt that getting his hands on a copy of the Discourses was one of the key events in his life. What’s the significance of saying that it came from Rusticus’ private library?

Arrian wrote an introduction to the Discourses saying that he’d only intended them to be circulated in private among his friends but, somehow, they had leaked into the public domain. It’s tempting, therefore, to imagine that, as a youth, Marcus felt he’d narrowly missed the opportunity to meet the most acclaimed philosopher of his era, and assumed that he left behind no writings. It would have been a breathtaking experience for him to be told by Rusticus, his Stoic teacher, that, in fact, copious notes from the lectures of Epictetus had been preserved by Arrian. We can imagine that it would have been a life-changing event for Marcus to be handed a rare copy of the Discourses, therefore, from the private collection of Rusticus — at the time, quite possibly, Marcus had no idea these writings even existed.

Whereas four volumes of Epictetus’ Discourses survive today, there were originally eight – half of them are now lost.

It seems virtually certain the “notes” (hypomnemata) were what we now call The Discourses, written and edited by Arrian. Indeed, Marcus quotes several passages, which are found in The Discourses. However, whereas four volumes of Epictetus’ Discourses survive today, there were originally eight – half of them are now lost. In addition to the quotations from the surviving Discourses, however, in the Meditations, Marcus appears to attribute a saying and several more passages to Epictetus. It seems quite likely that one or more of these may come from the lost Discourses.

Marcus doesn’t always cite the name of the author he’s quoting, or even indicate when something is a direct quote or paraphrase from another text. So it’s quite possible that there are other passages in The Meditations which actually quote or paraphrase Epictetus’ lost Discourses. Some of the sayings popularly attributed to Marcus, for all we know, could be quotations from other authors, especially Epictetus. As we’ll see, Marcus alludes to Epictetus more often than any other author in the Meditations, although Heraclitus perhaps comes a close second.

Epictetus in The MeditationsMarcus mentions Epictetus by name in the illustrious company of Chrysippus and Socrates, which seems to confirm the exceptionally high regard in which he held him. We should remind ourselves that for Marcus, Epictetus was a contemporary whereas Socrates and Chrysippus were famous sages, from four or five centuries earlier in history. It would be a bit like comparing a living scientist to Isaac Newton and Galileo, perhaps, only more so.

How many a Chrysippus, how many a Socrates, how many an Epictetus has eternity already engulfed. (7.19)

Elsewhere, Marcus quotes from Discourses (1.28 and 2.22) where Epictetus paraphrases Plato’s Sophist.

‘No soul’, he said, ‘is willingly deprived of the truth’; and the same applies to justice too, and temperance, and benevolence, and everything of the kind. It is most necessary that you should constantly keep this in mind, for you will then be gentler towards everyone. (7.63)

The word “he” probably refers either to Socrates or Epictetus.

In another passage, he attributes a saying to Epictetus not found in The Discourses, which is numbered Fragment 26. The use of the Greek diminutive (“little soul”) is certainly typical of Epictetus’ way of speaking.

You are a little soul carrying a corpse around, as Epictetus used to say. (4.41)

Marcus repeats this phrase again later, suggesting that it was particularly significant to him, although the meaning is somewhat obscure to us now:

Children’s fits of temper, and ‘little souls carrying their corpses around’, so that the journey to the land of the dead appears the more vividly before one’s eyes. (9.24)

The phrase seems intended to remind us that reputation and possessions are extraneous, i.e., to puncture our ego and bring us back down to earth. Imagine, for a moment, that Rusticus, Marcus’ very direct and confrontational Stoic mentor, told him, the future emperor of Rome, that he was not really a Caesar but rather a little soul carrying around a bag of flesh and bones, like everyone else, and that his anger, even over the most important matters of state, was no more rational than the temper tantrum of a small child.

Marcus also appears to have a well-known saying of Epictetus in mind when he writes:

You can live here on earth as you intend to live once you have departed. If others do not allow that, however, then depart from life even now, but do so in the conviction that you are suffering no evil. “Smoke fills the room, and I leave it”: why think it any great matter? (5.29)

Elsewhere he appears to be quoting the Stoic slogan of Epictetus “bear and forbear” (or “endure and renounce”, Marcus uses the same Greek words as Epictetus). This phrase, incidentally, does not occur in the extant Discourses, but is known from other sources, providing further evidence that Marcus had read more of Epictetus than we have today.

Wait with a good grace, either to be extinguished or to depart to another place; and until that moment arrives what should suffice? What else than to worship and praise the gods, and do good to your fellows, and “bear” with them and “forbear”; but as to all that lies within the limits of mere flesh and breath, to remember that this is neither your own nor within your own control. (5.33)

In addition to these, Book 11 of The Meditations concludes with a flurry of quotations or paraphrases from The Discourses. The first is clearly from Discourses 3.24.86-7.

It takes a madman to seek a fig in winter; and such is one who seeks for his child when he is no longer granted to him. (11.33)

Epictetus is named by Marcus in the next one, which is from Discourses 3.24.28.

Epictetus used to say that when you kiss your child you should say silently ‘Tomorrow, perhaps, you will meet your death.’—But those are words of ill omen.—‘Not at all,’ he replied, ‘nothing can be ill-omened that points to a natural process; or else it would be ill-omened to talk of the grain being harvested.’ (11.34)

Then he quotes from Discourses 3.24.91-2.

The green grape, the ripe cluster, the dried raisin; at every point a change, not into non-existence, but into what is yet to be. (11.35)

Then from Discourses 3.22.105, a phrase which Epictetus repeated several times elsewhere.

No one can rob us of our free will, said Epictetus. (11.36)

This is followed by Epictetus Fragment 27, which appears to be from a lost book of the Discourses or perhaps from notes taken down by another student:

He said too that we ‘must find an art of assent, and in the sphere of our impulses, take good care that they are exercised subject to reservation, and that they take account of the common interest, and that they are proportionate to the worth of their object; and we should abstain wholly from immoderate desire, and not try to avoid anything that is not subject to our control’. (11.37)

Epictetus Fragment 2 also apparently from a lost book of the Discourses, but related to Discourses 1.22.17-21.

‘So the dispute’, he said, ‘is over no slight matter, but whether we are to be mad or sane.’ (11.38)

That appears to be linked to the last passage, a mini Socratic dialogue, which is probably also derived from one of the lost Discourses.

Socrates used to say, ‘What do you want? To have the souls of rational or irrational beings?’ ‘Of rational beings.’ And of what kind of rational beings, those that are sound or depraved?’ ‘Those that are sound.’ ‘Then why are you not seeking for them?’ ‘Because we have them.’ ‘Then why all this fighting and quarrelling?’ (11.39)

As Marcus clearly groups quotations together, it’s possible that some of the other passages surrounding those mentioned above, or elsewhere in The Meditations, could be quotes or paraphrases from The Discourses, or in some cases quotes from other authors cited in The Discourses.

Thank you for reading Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life. This post is public so feel free to share it.