How to Make a Book

For me, the hardestpart of making a book is deciding what to say. In the Middle Ages, there wasmore to it than that, as I learned when researching the technology ofbook-making for The Abacus and the Cross. This week and next, I'll share what I found out.

CoolTour Bobbio: Today the greatest Christian library of the early MiddleAges—at the Italian monastery of Bobbio—is empty. Half of its 690 books went toMilan in the 1400s; from there, in the 1600s, some were sent to the Vatican. In1803, after Napoleon shut down the monastery, the remaining manuscripts wereauctioned off. Many were bought by the National Library of Turin, which burneddown in 1904. "We don't have even one to show the kids," Jessica Lavelli told me."The library in Milan will not even lend us one."

An energetic young woman committed to Bobbio's reputation asthe library that "saved civilization" (Thomas Cahill, author of How the Irish Saved Civilization,visited Bobbio, which was founded by an Irish monk), Lavelli makes up withimagination what she lacks in resources. She calls her project CoolTour. FromOctober to March, she invites one school group a week into the monastery andteaches them how to make a manuscript; in April and May, it's thirty kids aday. "They come from all over northern Italy: Milan, Genova, Brescia, Parma,Cremona. Anywhere that's less than two hours by bus."

After a tour of the ancient walled town, with its castle onthe hill and its hump-backed Roman bridge over the rushing river Trebbia, thechildren march through the arched gate behind the basilica and into thehigh-walled monastery complex. They pass through the cloister, its shady,columned arcades opening onto a sunny square where the monks would have hadtheir herb garden, into a pair of bright classrooms; there they are issuedgoose quills, ink, and parchment. They learn the history of script fromhieroglyphics to computer typesetting and how to make a book starting with thesheep.

Parchment: In one corner stands a sample of parchment stretched on adrying frame. "I got a sheepskin from a brasserie, a butcher, last spring,"Lavelli told me. "In Italy, it's common to eat sheep for Easter, so they hadmany skins. A lamb would be half this size. From one sheep you can get twopages—four sides when it's folded. From a lamb you only get one."

How did she learn to make parchment? "From a book. We founda book and tried to do it. It's a very long process. It takes four days toprepare and one week to dry, so after about ten days we can cut out our page.You dry it not in the sun or in the dark, but in the penumbra. We put it here"—she motioned toward a shady niche in thecloister where high walls block the sun from three directions. "The smell ofthe skin is not good," she added, wrinkling her nose. "When it stops smelling,it's dry."

According to Pliny's NaturalHistory, written in the first century A.D., parchment—in Latin, pergamenum—was invented for the king ofPergamos (modern Bergama, Turkey) to break the Egyptian monopoly on papyrus. Thesedge used for papyrus was common only on the banks of the Nile. Sheepskinswere everywhere.

The oldest known recipe for turning sheepskin into parchmentwas written in the Italian city of Lucca at the end of the eighth century."Place it in limewater," it says, "and leave it there for three days and extendit on a frame and scrape it on both sides with a razor and leave it to dry,then do any kind of smoothing that you want." A twelfth-century manuscript offers more precise—but still somewhatmysterious—instructions on how "to make parchment from goatskins as it is donein Bologna"; this process takes twenty-four days plus drying. Book conservatorLeandro Gottscher compared the two methods during a series of experiments onehot summer in Rome in the 1990s. Both made acceptable parchment, though theshorter soaking time made for harder work scraping off the hair.

The oldest known recipe for turning sheepskin into parchmentwas written in the Italian city of Lucca at the end of the eighth century."Place it in limewater," it says, "and leave it there for three days and extendit on a frame and scrape it on both sides with a razor and leave it to dry,then do any kind of smoothing that you want." A twelfth-century manuscript offers more precise—but still somewhatmysterious—instructions on how "to make parchment from goatskins as it is donein Bologna"; this process takes twenty-four days plus drying. Book conservatorLeandro Gottscher compared the two methods during a series of experiments onehot summer in Rome in the 1990s. Both made acceptable parchment, though theshorter soaking time made for harder work scraping off the hair.The limewater is the key to the process. It was made byburning crushed limestone (or marble, chalk, or shells) in a kiln to makequicklime, placing that in a vat or barrel, and adding a little water. Thelimewater would seethe and bubble and be ready in about ten minutes. Gottscherspread a pulp of limewater onto the skin, folded it, and set it aside for a fewdays. Other experimenters prefer to dilute the limewater until it is milky andsoak the skin. The lime eats into the epidermis, the outer layers of the skin,loosening the hair on one side and the fat on the other.

To remove the hair, rinse off the lime and pull or pluck outwhatever hair you can. (Gloves are a good idea—any remaining lime will eat intoyour skin too.) Next lay the skin over a log or trestle and rub it with awooden hone, a bone spatula, or a dull knife, a procedure called scudding.

To remove the fat, the hairless skin can be dunked in freshlimewater or rubbed with lime powder, then spread on the trestle, hair-sidedown, and scudded again. Lean sheep make better parchment than fat ones; excessfat makes the parchment slippery and the ink doesn't stick. On the other hand,parchment that is scraped too thin can become wrinkly and transparent.

The dehaired and defatted skin is soaked again and stretchedonto a wooden frame to dry. To avoid tearing holes, first wrap a corner of skinaround a pebble (called a pippin),tie one end of a cord around the pippin and another to a wooden peg in theframe. As the skin dries, tighten the pegs.

While leather-making is a chemical process, parchment-makingis a physical process. What's left after all the soaking and scudding is mostlycollagen, long spiraling proteins that form tough, elastic fibers. As the skindries, these fibers try to shrink. Stopped by the frame, instead the fibers'structure begins to change.

When it's dry, the parchment is scraped again, still on theframe, with a crescent-shaped blade called a lunellum ("little moon"), powdered again with lime or chalk tobleach it, and rubbed thoroughly on both sides with a pumice stone to raise anap. Then it is taken down and cut into sheets of a standard size. The firstsheet is easy: a rectangle that, folded, could become four pages of a largebook (or eight pages of a small one). Then the cutter has to become creative: Asheepskin is not square. Where the head, legs, and tail were cut off, the skincurves. Scholars often come across manuscript pages with a corner missing—wherea page runs into a neck hole. Other blemishes are insect bites (little holes),wounds on the animal (bigger holes), and gashes (where the knife slipped duringthe flaying); some of these are sewn up, but usually the scribe just wrotearound them.

When it's dry, the parchment is scraped again, still on theframe, with a crescent-shaped blade called a lunellum ("little moon"), powdered again with lime or chalk tobleach it, and rubbed thoroughly on both sides with a pumice stone to raise anap. Then it is taken down and cut into sheets of a standard size. The firstsheet is easy: a rectangle that, folded, could become four pages of a largebook (or eight pages of a small one). Then the cutter has to become creative: Asheepskin is not square. Where the head, legs, and tail were cut off, the skincurves. Scholars often come across manuscript pages with a corner missing—wherea page runs into a neck hole. Other blemishes are insect bites (little holes),wounds on the animal (bigger holes), and gashes (where the knife slipped duringthe flaying); some of these are sewn up, but usually the scribe just wrotearound them.The color of parchment depends partly on the process andpartly on the animal it came from. Low-grade parchment could be darkpinkish-brown with a chalky surface, peppered with hair follicles, streakedwith scrape marks, or so thin that the ink bled through. Sheepskin, well cured,was "butter-white" or yellowish, but still sometimes greasy or shiny. Goatskinwas greyish. Calfskin was the whitest, though the veins could be prominent. Theparchment Jessica Lavelli made to show her pupils at Bobbio had a large brownspot. She shrugged. "It was a spotted sheep! I didn't think it would matter."

If you visit Bobbio, check out CoolTour and say hello toJessica for me: http://www.cooltour.it/

For an overnight stay, I recommend the farm guesthouse SanMartino. It is (of course!) a horse farm within walking distance of the town: http://www.agriturismo-sanmartino.com/

Bobbio has also been recently identified as the town paintedin the background of the Mona Lisa. As one newspaper said, "brace fortourists"! http://www.newser.com/story/109501/art-historian-identifies-mona-lisas-home-town.html

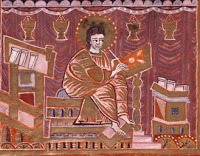

Photos: Saint Luke at his writing desk, from Bernward's Evangelary (Dom Museum Hildesheim). The town of Bobbio, Italy. Portrait of a scribe from the CoolTour Bobbio website. Detail of a Bobbio manuscript, also from CoolTour Bobbio.

Published on April 11, 2012 08:10

No comments have been added yet.