Davies on classical theism and divine freedom

I’ve long regarded Brian Davies’

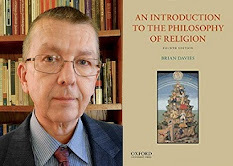

An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion

as the best introduction to that field on the market. A fourth edition appeared not too long ago, and I’ve been meaning to post something about it. Like earlier editions, it is very clearly written and accessible, without in any way compromising philosophical depth. Its greatest strength, though, is the attention it gives the classical theist tradition in general and Thomism in particular, while still covering all the ground the typical analytic philosophy of religion text would (and, indeed, bringing the classical tradition into conversation with this contemporary work). The fourth edition adds some new material along these lines.

I’ve long regarded Brian Davies’

An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion

as the best introduction to that field on the market. A fourth edition appeared not too long ago, and I’ve been meaning to post something about it. Like earlier editions, it is very clearly written and accessible, without in any way compromising philosophical depth. Its greatest strength, though, is the attention it gives the classical theist tradition in general and Thomism in particular, while still covering all the ground the typical analytic philosophy of religion text would (and, indeed, bringing the classical tradition into conversation with this contemporary work). The fourth edition adds some new material along these lines. Davies is well-known for contrasting classical theism (represented by Augustine, Anselm, Aquinas, Maimonides, Avicenna, et al.) with what he calls the “theistic personalism” that is at least implicit in thinkers like Richard Swinburne, Alvin Plantinga, open theists, and others. The difference between the views is that theistic personalists reject divine simplicity and, as a consequence, often reject other classical attributes such as immutability, impassibility, and eternity. (Davies acknowledges that not all those he labels “theistic personalists” agree on every important issue and that they don’t necessarily self-identify as theistic personalists. But he’s identifying a trend of thinking that really does exist in contemporary philosophy of religion, even if those contributing to it do not always realize they are doing so.)

Among the important additions to the new edition are a few pages addressing the question of whether, given the significant differences between classical theists’ and theistic personalists’ conceptions of God, they are even really referring to the same thing when they use the word “God.” Davies suggests that it may be that “if differences in beliefs about God on the part of classical theists and theistic personalists are serious and irreconcilable, then classical theists and theistic personalists do not believe in the same God” (p. 19). But he also urges caution and acknowledges that everything hinges on what counts as “serious and irreconcilable.” He does not attempt to resolve the matter, but recommends looking at Peter Geach’s treatment of the question (which I discussed in a post some years back).

Several new pages are also added to the previous edition’s discussion of divine freedom in the chapter on divine simplicity. (Davies’ views on this issue were the subject of another post from years ago.) Critics of divine simplicity often argue that it is incompatible with God’s having freely created the universe. For if God could have done other than what he has in fact done, doesn’t that entail that God is changeable, contrary to divine simplicity? And if he is in fact unchangeable or immutable, doesn’t that entail that he could not have done otherwise, and thus created of necessity rather than freely? In response, Davies points out, first, that creating freely simply does not in fact entail changing. Certainly it simply begs the question to assume otherwise. For the classical theist, God creates eternally or atemporally, and what is eternal or atemporal does not undergo change. Still, he could have done otherwise than create, so that this eternal act of creation is free.

Second, Davies notes that in order to show that an eternal and immutable God’s act of creation would be unfree, one would have to show that there is something either internal to God’s nature or external to him that compels him to create. But given that the divine nature is as classical theists, on independent grounds, argue it to be (pure actuality, perfect, omnipotent, etc.) there can be no need in God for anything distinct from him, so that nothing in his nature can compel him to create. And since, the classical theist also argues (and again on independent grounds) there is nothing apart from God that God did not create, there can be nothing distinct from him that compels him to create. Hence we cannot make sense of God’s being in any way compelled to create, and thus must attribute freedom to him.

Third, Davies notes that those who suppose that freedom in God would entail changeability often presuppose an anthropomorphic conception of divine choice. In particular, they imagine it involving a temporal process of weighing alternative courses of action before finally deciding upon one of them. But that is not what God is like, given that he is eternal or outside time, and that he is omniscient and doesn’t have to “figure things out” through some kind of reasoning process.

Fourth, Davies notes that critics of the doctrine of divine simplicity argue that the doctrine implies that God is identical to his act of creation, and that accordingly, if God exists necessarily, then his act of creation is necessary. But if it is necessary, they conclude, then it cannot be free. In reply, Davies distinguishes between an actconsidered as something an agent does, and what results from an act, which is external to the agent. He then argues that even if God’s act, being identical to him, is necessary, it doesn’t follow that the result of that act (namely, the created world) is necessary.

Finally, Davies emphasizes that “to speak of God as simple is not to attribute a property to God but to deny certain things when it comes to God” (p. 179). Here, as he has in other work, Davies emphasizes the idea that the ascription of attributes to God should be understood as an exercise in negative or apophatic theology. The main arguments for classical theism, he points out, emphasize both that the world is contingent or conditioned in various respects, and that an ultimate explanation of the world must be unconditioned and non-contingent in those respects. (Though, just in case he wouldn’t himself use it, I should note that the language of “conditioned” and “unconditioned” in this context is mine, not Davies’.) In particular, God must not be changeable, must not have properties that are distinct from each other or from him, and so on. This is what it means to characterize him as simple. But by the same token, he must not be compelled to create by anything either internal to his nature or outside of him. Hence divine simplicity, divine freedom, and the relationship between them are properly understood as characterizations of what God is not.

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 329 followers