Another Blizzard in Crypto Winter, or, Tinker Bell Economics: To Call Crypto a “Trustless” System is a Joke

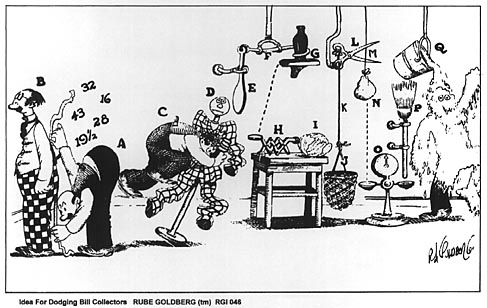

Another blizzard hit the winter-bound crypto industry, with the evisceration of crypto wonder boy Sam Bankman-Fried’s (SBF to crypto kiddies) FTX and its associated hedge fund Alameda Capital. (Which should be renamed Alameda No Capital.) The coup coup de grâce was delivered by SBF’s former frenemy (now full fledged enemy), Binance’s Changpeng Zhao (CZ, ditto). But it is now evident that FTX was a Rube Goldberg monstrosity and all CZ did was remove–call into question, really–one piece of the contraption which led to its failure.

The events bring out in sharp detail many crucial aspects of the crypto landscape. (I won’t say “ecosystem”–a nauseating word.).

One is crypto market structure. FTX (and Binance for that matter) are commonly referred to as “exchanges,” giving rise to thoughts of the CME or NYSE. But they are much more than that. FTX (and other crypto “exchanges”) are in fact highly integrated financial institutions that combine the functions of trade execution platform (an exchange qua exchange), a broker dealer/FCM, clearinghouse, and custodian. And in FTX’s case, it also was affiliated with a massive crypto-focused hedge fund, the aforementioned Alameda.

Crucially, as part of its broker dealer/FCM operation, FTX engaged in margin lending to customers. Indeed, it permitted very high leverage:

FTX offers high leverage products and tokens. The exchange currently offers 20x maximum leverage, down from its previous 101x leverage products. This is still one of the highest maximum leverage a crypto exchange offers when compared to FTX’s other competitors. Leveraged long and short tokens for BTC, ETH, MATIC, and others are also offered by the exchange; for example, the ETHBULL token allows investors to trade a 3x long position in Ethereum.

FTX also engaged in the equivalent of securities lending: it lent out the BTC, etc., that customers held in their accounts there.

These are traditional broker dealer functions, and historically they are functions that have led to the collapse of such firms–more on that below.

FTX supersized the risks of these activities through one of its funding mechanisms, the FTT token. Ostensibly the benefits of owning FTT were reduced trading fees on the exchange, “airdrops” (a distribution of “free” tokens to those holding sufficient quantities on account with FTX, a promise to return a certain fraction of trading revenues to token holders by repurchasing (“burning”), and some limited governance/voting rights. The burning also served the function of limiting supply. (I plan to write a separate post on the economics of valuation of these tokens, though I do touch on some issues below.)

So FTT is (or should I say “was”?) stock-not-stock. Not a listed security, but an instrument that paid dividends in various forms.

FTT was in some ways the snowman here. For one thing, FTX allowed customers to post margin in FTT.

Huh, whut?

Risky collateral is always problematic. (Look at the reluctance of counterparties to accept anything but cash as collateral even from pension funds as in the UK.) Allowing posting of your own liability as collateral is more than problematic–it is insane. Very Enron-y!

Why? A subject I’ve written on a lot in the past: wrong way risk.

If for any reason FTT goes down, the value of collateral posted by customers goes down. Which means that your assets (loans to customers) go down in value.

A doom machine, in other words.

The integrated structure of FTX exacerbated this risk, and bigly. If customers start to get nervous about its viability, they start to pull the assets (BTC, ETH, etc.) they have on account there. Which is a problem if you’ve lent them out! (Recall that AIG’s biggest problem wasn’t CDS, but securities lending.)

And this has happened, with customers attempting to pull billions from the firm, and FTX therefore being forced to stop withdrawals.

And things can get even worse. The travails of a big broker dealer can impact prices, not just of its liabilities like FTT but of assets generally (stocks and bonds in a traditional market, crypto here) and given the posting of risky assets of collateral that can make the collateral shortfalls even worse. Fire sale effects are one reason for these price movements. In the case of crypto, the failure of a major crypto firm calls into question the viability of the asset class generally, with some of them being affected particularly acutely.

The integrated structure of crypto firms is also a problem. Customer assets are held in omnibus accounts, not segregated ones. Yeah yeah crypto firms say your assets on account are yours, but that’s true in a bookkeeping sense only. They are held in a pool. This structure incentivizes customers to run when the firm looks shaky. Which can turn looks into reality. That’s what has happened to FTX.

The connection with a hedge fund trading crypto is also a big problem. (The blow up of hedge funds operated by big banks was a harbinger of the GFC in August, 2008, recall.). And it is increasingly apparent that this was a major issue with FTX that interacted with the factors mentioned above. FTX evidently lent large amounts–$16 billion!–of customer assets to Alameda Research. Apparently to prop it up after huge losses in the first blizzards of Crypto Winter. (In retrospect, SBF’s buying binge earlier this year looks like gambling for resurrection.)

SBF described this as “a poor judgment call.”

You don’t say! I hear that’s what Napoleon said while trudging back from Russia in November 1812.

Also probably an illegal judgment call.

But it gets better! Alameda held large quantities of FTT, also apparently emergency funding provided by FTX. And it used billions of FTT as collateral for its trades and borrowing.

And this was the string that CZ pulled that caused the whole thing to unravel. When he announced that he had learned of Alameda’s large FTT position, and that as a result he was selling FTT the doom machine kicked into operation, and at hyper speed: doom occurred within days.

Looking at this in the immediate aftermath, my thought was that FTX was basically MF Global with an exchange operation. A financially fragile broker dealer combined with an exchange.

Think of MF Global operating an exchange.

— streetwiseprof (@streetwiseprof) November 8, 2022

And the analogy was even closer than I knew: FTX’s using customer assets to “fund risky bets” revealed this morning is also exactly what MF Global did. Except that Corzine was a piker by comparison. He filched almost exactly only 1/10th of what FTX did ($1.6 billion vs. $16 billion). (Maybe SBF should take comfort from the fact that Corzine walks free–though I don’t recommend that he walk free at LaSalle and Jackson or Wacker and Adams). (I further note that SBF is a huge Democrat donor. Like Corzine, his political connections may save him from the pokey, though by all appearances he should spend a very long stretch there.)

In sum, FTX’s implosion is just a crypto-flavored example of the collapse of an intermediary the likes of which has been seen multiple times over the (literally) centuries. As I’ve written before, there is nothing new under the financial sun.

The episode also throws a harsh light on the supposed novelty of crypto. Remember, the crypto narrative is that crypto is decentralized, and does not rely on trusted institutions: it is trustless in other words.

Wrong! As I’ve written before, economic forces lead to centralization and intermediation in crypto markets, just as in traditional financial markets. Market participants utilize the services of firms like FTX and Binance, and have to trust that those firms are acting prudently. If that trust is lost, disaster ensues.

In brief, crypto trading could be decentralized, but it isn’t. For reasons I wrote about years ago. (Also see here.)

Indeed, the issue is arguably even more acute in crypto markets, for a reason that SBF himself laid out in now infamous interview with Matt Levine on Odd Lots. Specifically, that token valuation relies on magic–belief, actually.

That is, tokens are valuable if people believe they are valuable–that is, if they have trust in their value. Furthermore, there is a sort of information cascade logic that can create market value: if people see that a token sells at a positive price–especially if it sells at a very large positive price–and they observe that supposedly smart people hold it, they conclude it must have some intrinsic value. So they pile in, increasing the value, validating beliefs, and extending the information cascade.

But this is Tinker Bell economics. If people stop believing, Tinker Bell dies.

And when someone very influential like CZ says “I don’t believe” death is rapid: the information cascade stops, then reverses. Especially given how FTT was the keystone of the FTX arch.

In brief, crypto theory is completely different than crypto reality. Crypto markets share all major features with the demonized traditional “trust-based” financial system. To the extent they differ, they are even more based on trust, given the ubiquity of Token Tinker Bell Economics.

Craig Pirrong's Blog

- Craig Pirrong's profile

- 2 followers