I'm a huge fan of science fiction and regularly

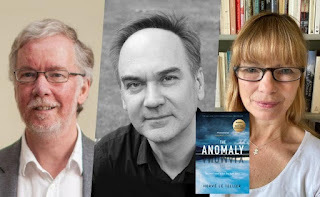

review SF books on my popularscience.co.uk blog. It seems a truism that science fiction should involve science and/or technology - but is it an essential? This is one the topics that is likely to be discussed when I meet up for an on-stage chat with bestselling French author Hervé Le Tellier, chaired by the translator of his remarkable novel

Anomaly, Adriana Hunter.

If you are in London on 22 May 2022 and fancy coming along, the event, part of the Beyond Words Festival, is on at the Institut Français at 5pm.

Tickets are available here.

What makes a book SF is always a subject of dispute, but for me it should reflect the human consequences of some kind science or technology. Sometimes this is straightforward - taking in the impact of, say, artificial intelligence or spaceflight. But science fiction also has certain standard concepts, such as faster than light travel or time travel that are not possible with current technology and may never be.

On the whole, the distinction between SF and fantasy in such circumstances is that science should not totally exclude the possibility of what's happening. There are physical mechanisms that could, in principle, get around the light speed limit, or the inability to travel through time. But what should we think when the 'science' that the premise is based on is not science at all?

That's where Anomaly comes in. I don't think it's too much of a spoiler to say that the plot of Anomaly involves the simulation hypothesis. This is the idea that everything we experience is not physically real but takes place in a vast computer simulation - The Matrix on steroids. For me, the simulation hypothesis is fun to consider, but is more a matter of philosophy than science.

For a hypothesis to be scientific there has to be some way in principle to test out that hypothesis. We may not be able to undertake the test right now, but it should be possible. Yet the simulation hypothesis does not allow us to do this. To see why, it's useful to bring in the similar but simpler invisible dragon hypothesis. I have a theory that there is an invisible dragon in my garage. Is that science? It's certainly possible to make any scientific test you propose incapable of disproving my hypothesis.

For example, if you try to detect the presence of my dragon by scattering flour on the floor to pick up footprints, I will point out that my invisible dragon is weightless, floating just above the surface of the ground. If you listen for its breathing I will tell you that my dragon does not breathe. If you want to detect it with a heat gun, I will point out that it emits no infra-red. My dragon could exist. But if there is nothing to measure, nothing to observe, science can say nothing useful about it. It isn't a scientific hypothesis.

Some argue that the same problem applies to concepts that are often considered scientific, such as string theory. And it certainly also applies to the simulation hypothesis. If we accept that what we are dealing with is speculative philosophy rather than science, can it really be the basis for science fiction? Some like the term 'speculative fiction' a weak alternative meaning of SF, but (perhaps surprisingly) I think a book like Anomaly can still legitimately be regarded as science fiction.

This is because, in the end, it's the 'fiction' part that matters most. It helps that I do like the occasional alternate history book, such as Kingsley Amis's

The Alteration

and Keith Roberts'

Pavane. Arguably the mechanism of alternate history is not strictly science - but the result is still far closer to SF than it is to fantasy. Similarly, even though the 'science' of a book like

Anomaly is totally speculative and incapable of being tested, it feels more like science fiction than fantasy - and that's good enough for me.

I hope you can join us on 22 May 2022 for what should be a lively discussion.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Dennis39784 wrote: "Settings in stories alone don't make them Sci-Fi. Even stories set in distant futures and galaxies like Star Wars are more Space Fantasies than anything involving science. Science sounding book tit..."

Dennis39784 wrote: "Settings in stories alone don't make them Sci-Fi. Even stories set in distant futures and galaxies like Star Wars are more Space Fantasies than anything involving science. Science sounding book tit..."

To me, Sci-Fi books must either extend contemporary technologies or science into new worlds ("Martian Chronicles," Bradbury), or spend serious efforts explaining the scientific mechanisms behind the fantasia ("2313," Robinson; "The Three-Body Problem," Liu).

As you've said, "Fiction" is the main focus of these stories, and good ones deserve appreciative audiences regardless of the label. If it feel like Sci-Fi, "May the 4th Be With You."