Scurrilous accusations

On 3 February this year, Munira Mirza, the UK Prime Minister’s policy chief, who had worked with him for fourteen years, resigned. She released a letter, parts of which are included at the end of this post. The straw that broke this camel’s back was that Boris Johnson had personally blamed the leader of the opposition, Sir Keir Starmer, for letting a (now) notorious multiple sexual abuser escape justice when Starmer was the Director of Public Prosecutions, aka the head honcho of the Crown Prosecution Service.

Many journalists picked up on a single word in her resignation letter: scurrilous. The reason seems fairly obvious: scurrilous accusation is a great soundbite. That said, I can’t help wondering, cynic that I am, about a couple of other things. Did the hacks relish it because it’s not a word you come across every day? And how many people googled it to find out what it means? It also has a very particular ‘mouthfeel’ as the oenophiles might say. The only other word containing the string of letters –rilous is perilous and its opposites. No other words contain the string –urrilous.

To what, then, does it owe its seemingly unique shape?

Where does the word come from?Scurrilous has been in English since the sixteenth century, according to the OED. Since 1576, to be precise. In A Winter’s Tale (1623; 1609-11) Perdita tells the servant to forewarn Autolycus that he ‘use no scurrilous words in’s tunes’. Given the bawdiness often underlying Shakespeare’s language, one sympathises with her request.

Scurrilous is the anglicised version of scurrile (1547; pronounced/ˈskʌrɪl/), which lingered on until the nineteenth century. And scurrile comes either from the same French form or from Latin scurrīlis, which in turn is a derivative of Latin scurra, a buffoon, according to Lewis and Short, ‘A city buffoon, droll, jester (usually in the suite of wealthy persons, and accordingly a kind of parasite; …)

What exactly does it mean?Collins Cobuild, based on corpus data, has an excellent definition:

Scurrilous accusations or stories are untrue and unfair, and are likely to damage the reputation of the person that they relate to.

That perfectly describes Boris Johnson’s jibe.

Cobuild then gives these two examples:

Scurrilous and untrue stories were being invented.

…scurrilous rumours.

The most common nouns it qualifies according to Collins Bank of English are rumours, slander, gossip, tittle–tattle and accusations. The adjectives it often appears together with are unfounded, contemptible, slanderous and untrue.

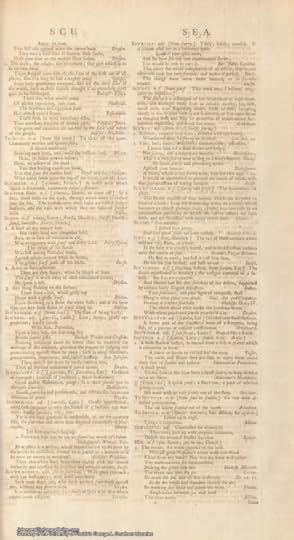

Doctor Johnson defined scurrilous multiply thus:

Grossly opprobrious ; using such language as only the licence of a buffoon can warrant ; loudly jocular ; vile ; low.

Some commentators might find that second definition particularly apposite for Boris Johnson. Perhaps as a classicist, he will have savoured the word.

Extracts from the Munira Mirza’s resignation letter“I believe it was wrong for you to imply this week that Keir Starmer was personally responsible for allowing Jimmy Savile to escape justice. There was no fair or reasonable basis for that assertion. This was not the usual cut and thrust of politics.”

[…]

You are a man of extraordinary abilities with a unique talent for connecting with people.

You are a better man than many of your detractors will ever understand which is why it is desperately sad that you let yourself down by making a scurrilous accusation against the Leader of the Opposition.”