Christmas Isn’t Over Yet

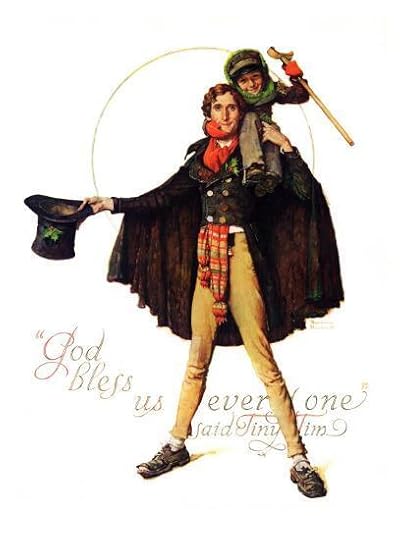

As you may know, I write historical fiction set in early 19th century England, a period called the Regency era. A large part of writing fiction set in another country more than 200 years ago is research, which I (thankfully) enjoy. I have especially found it interesting to discover similarities and differences between how the British used to celebrate Christmas—and in many cases still do—compared to how Americans celebrate today. (Research that helped me to write An Ivy Hill Christmas, which came out last year.)

In America, our yuletide celebrations seem to culminate on Christmas Day, with one last hurrah on New Year’s Eve. But in 19th century England, celebrations extended longer. After all, the Twelve Days of Christmas begin on December 25th and continue all the way until January 5th or 6th to Twelfth Night or Epiphany.

And, in the early 19th century, festivities centered more on socializing and less on gift-giving. Charity was also a big part of an old English Christmas.

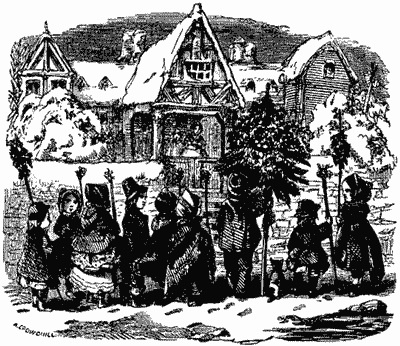

For example on December 21st people observed St. Thomas Day. On this day, elderly women and poor widows went to the homes of their wealthier neighbors to gather gifts of food or money to help them celebrate Christmas. It was not considered begging on this day, but their due. It was called “Thomasing,” or in some places “mumping,” or “a-gooding.” The women might sing or give out sprigs of holly or mistletoe. In return, wealthy landowners would give them a little money or parcels of wheat and tea, which were very expensive then.

Women “Thomasing”

Women “Thomasing”But it was not only the very wealthy who were charitable. Many people prepared extra food to share with the less fortunate. Here’s a line from a letter from 1818:

I have been busily employed in preparing for passing Christmas worthily. My beef and mincemeat are ready (of which, my poor neighbors will partake), and my holly and mistletoe gathered.”

—A letter from “a wife, a mother, and an Englishwoman”

Clergymen often hosted Christmas dinner after divine services for their poorer parishioners, as this diary entry from December 25th, 1784 illustrates:

I dined today at 1 o’clock and [several] poor old people here also. After they had dined, I gave to each one Shilling 0.7.0. Pray God ever continue to me the power of doing good.”

—James Woodforde, The Diary of a Country Parson

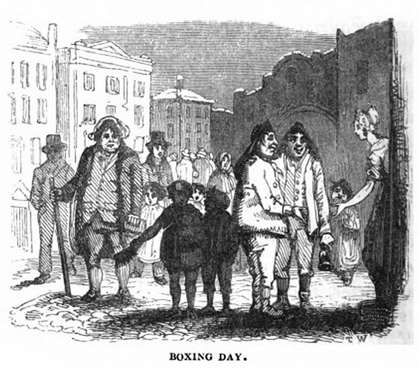

Boxing Day is another example. On December 26th, servants would traditionally have the day off, and they were given “boxes” containing gifts of cast-off clothing they could sell or make over (fabric was expensive), food like leftovers or preserved fruit, and perhaps a few coins.

Also, churches collected money in alms-boxes during the season and distributed it to the needy on this day. (Boxing Day is still observed in Britain, but from what I understand, it is now a day for shopping sales and relaxing.)

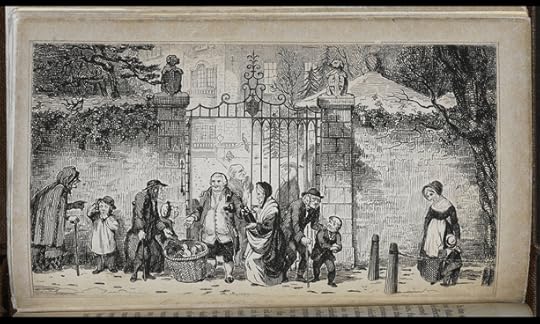

A wealthy gentleman distributes food to the poor on Boxing Day. Thomas Kibble Hervey, The British Library.

A wealthy gentleman distributes food to the poor on Boxing Day. Thomas Kibble Hervey, The British Library.At its heart, an old England Christmas was a time of family and faith, hospitality, and Christian charity, and those are things we can put into practice for all 12 days of Christmas, and all the year through.