My Mormon #MeToo Experience and the Language of Consent and Assault

CW: This post discusses experiences with sexual assault and abuse.

Four years ago, I watched the start of the viral hashtag MeToo on Twitter. At first, it was a trickle, and then a flood of people, mostly women, tweeting about their experiences with sexual assault. The hashtag was soon all over the internet, and it led to action and advocacy off-screen. It brought the necessary momentum to hold some perpetrators accountable for their actions and give a voice to some survivors.

It didn’t happen all at once—it took years—but #MeToo gave me the language to understand and talk about my own experiences with sexual assault.

As a girl raised in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I was given a lot of rules around my body and sexuality. Rules on modesty, dating, and chastity. Rules that told me that the existence of my body could be a stumbling block—even walking pornography—to the boys and men around me if I wasn’t careful. Rules that were sometimes vague or confusing (no leader was even clear on the definition of “petting”), and at other times inappropriately explicit (like when one of my bishops at BYU would go into detail about ways that girls masturbated).

But for all the rules, there was little to no talk of consent. There was no talk of grooming, manipulation, or abuse. And there was little sense that I had an immutable worth as a person and daughter of God.

I had my first kiss at a Pop Warner football game when I was twelve years old. It was a fairly simple, chaste kiss with a boy from school. I went home that night with stars in my eyes, thrilled at the experience. The next day in Young Women’s at church, the Beehives (ages 12-13) were combined with the Laurels (ages 16-18). The teacher handed out bookmarks resembling dollar bills with a message about how our kisses are like currency, and the more we give, the less they (and we) are worth. We needed to conserve our kisses so that they (and we) would be worth something to our future husbands. I went home and sobbed for hours. I knew I would not marry that boy, and I knew that I was now worth less (worthless?), and there was no way to reclaim that spent worth.

I knew and loved this leader. I believe she was doing her best with the messages that she had internalized. But this was the first of many lessons that taught me that the Atonement of Jesus Christ was not powerful enough to cover the romantic or sexual experiences of women, consensual or not, sinful or not.

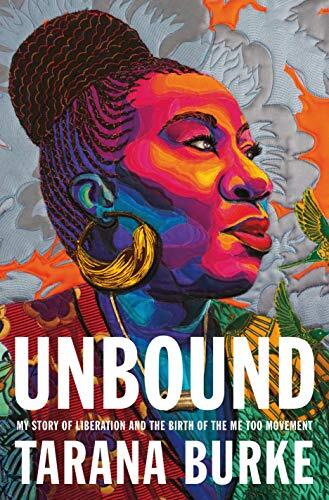

Fast forward to 2017, and #MeToo began trending—a phrase that Tarana Burke had been using for decades in her work as an advocate and activist in creating empathy around experiences of sexual assault. Burke works at the intersection of sexual violence and racial justice, creating movements to bring resources, education, and support for impacted communities. “Me Too” was a way that Burke created space for the mostly black and brown girls in her leadership workshops to talk about the violence in their lives. Her new memoir, Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too Movement, is the breathtaking, heart-wrenching, unflinchingly honest story of her experiences that brought her to this work.

When Burke shares her first experience of being sexually assaulted at age seven, she talks about her fear of being in trouble for all the rules she had broken in the process of her assault—such as “never go off without permission” and “never let anyone touch your private parts.” She was a child and none of this was consensual, but for all the rules she had been given, she hadn’t been taught that if something did happen to her, she was not to blame. Because she interpreted herself to have broken rules in the process of her assault, she believed she was responsible for her abuse. It took many years to consider herself a victim, let alone a survivor, of sexual assault.

I can’t say how many times I had to pause and take a breath while listening to Unbound. Times I had to go back and listen again. Times I wished I had heard these words when I was younger. Like Burke, I was given rules. I did not have an understanding of consent. I did not have a sense of my immutable worth.

Me at age 18

Me at age 18Like most women, I have many experiences with sexual harassment. But when I was eighteen years old, I was sexually assaulted on multiple occasions by a boyfriend. Because it was not what I would consider rape, I didn’t have the language to talk about my experiences. And because I was a BYU student, I felt unable to report my assault. At the time, if a student reported sexual assault and had broken ANY Honor Code rules in the process, the student could face school and/or church discipline for reporting. For many years, I didn’t tell anyone what I experienced.

#MeToo gave me the language to understand what had happened to me. When in 2020 I started meeting with a therapist, I was finally ready to talk. I first told a close friend, then my therapist, and then my husband. Over months, I told more friends and family members. And the relief that this brought me is hard to understate. I had suffered from the shame and trauma of my assault for fourteen years. But in the months that followed talking about my experience, I felt healing that I didn’t know was possible. After fourteen years, the flashbacks finally stopped. I felt more at home in my body, mind, and spirit. I felt more able to reclaim the immutable worth that had always been mine but had been blocked from me.

The #MeToo movement gave me the language and space to talk about my experiences and work towards healing. But too many survivors of assault do not have the freedom that the movement extended to me and others like me. Burke talks about how as the hashtag flooded the internet, the voices were disproportionately white, cishet women. Too many people of color and LGBTQIA+ individuals do not yet have the support or resources to share their stories. And too often, Nice White Parents work to keep out the educational resources from schools that will give the language and tools for prevention and healing.

It is not enough to give rules to our children and youth. They need education, a robust understanding of consent, and the safety and empathy necessary to talk about abuse and shame to build the resilience necessary to move forward.

For me, the language I gained from the #MeToo movement was liberating. I don’t think that every survivor needs to share the details of their abuse on the internet. But I hope that Burke’s words reach as many people as possible and continue to free those who are not yet free to move out from under shame and into joy.