To intend doing or to intend on doing? Which is correct?

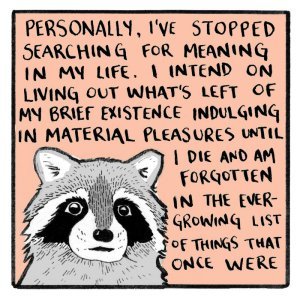

The other day a tweep – well, actually a renowned linguistics Professor – tweeted a cartoon including the frame shown below:

I agree with the sentiments but not the phrasing.

I agree with the sentiments but not the phrasing.Note that structure: ‘I intend ON living out what’s left of my brief existence…’

Shurely shome mishtake, I thought. Presumably a one-off.

But no, it’s not a one-off. More than that: it seems to be really quite common, especially, of course, in that hotbed of solecism ( ) the US.

) the US.

It’s been discussed on WordReference.com. A French speaker raised the issue there and was advised (sigh) by a Canadian TEACHER (double sigh) to use ‘intend on + –ING’, which was then marked wrong by their teacher. Whereupon, depressingly, others opined about the niceties of using intend on + –ING without quite twigging that IT IS PLAIN WRONG according to long-established syntax.

It is also covered in the comprehensive list of errors (also published as a book Common Errors in English Usage) of Professor Paul Brians.

So, is it ‘acceptable’?It’s non-standard. But that doesn’t stop it being quite frequent. (Rather like ‘hone in on’.)

As any dictionary or grammar will tell you, to intend can be followed by one of two structures: a to-infinitive or an –ING form. It’s one of those verbs that allow both forms with no difference of meaning (cf. to like doing/to do, bother…, start…, begin…, continue, etc.)

If I come across it in something I’m editing, should I change it?Up to you. But unless it’s part of a dialogue in the mouth of a character who uses non-standard or colloquial forms, some people will consider it wrong. Also, it depends, of course, on whether your editing style is to implement changes or merely notify the author about something you consider to be amiss.

How did it come to be?There’s a complicated theory and an easy one. The complicated one, which is mine, runs like this:

The adjective intent is used in the structure to be intent on doing something, i.e. to have a very strong desire and intention to do it, to be determined to do it. Its meaning thus overlaps with that of the verb to intend.

Somehow, at some stage people who said/wrote ‘to intend on doing something’ must have muddled the two structures up. It’s not obvious how, though.

‘Intent on’ usually has the verb ‘to be’ before it, so e.g. am/is/are/was/were intent on going. However, the t/d alternation is a fertile source of mistakes in English in eggcorns such as centripedal and mood point, so perhaps that’s the root of the problem. Take the phrase ‘I’m intent on going’, let that last t of intent be interpreted as a d and we get ‘I’m intend on going’. In rapid speech, I suppose that could be interpreted as ‘I intend on going.’

Convinced?

No, me neither, but I can’t work out how it could have happened otherwise. The easy answer, as suggested by Prof. Brians, is that the structure has been influenced by to plan on +-ING. That sounds very plausible to me. Regularisation of patterns seems to be a motor of language change/variety.

Perhaps it’s a mixture of those two factors mentioned.

Do let me know if you have – as I’m sure you will – any better suggestions. But anyway, the fact is that once the pattern started, thanks to the ubiquity of online writing and the ubiquity of ignorance it seems to have spread like wildfire.

It’s non-standard, but is it used a lot?Surprise, surprise. Yes! Three corpora consulted throw up these proportions:

Collins Bank of English (2012; 3 billion 670 million words, 4 billion 417 million tokens)intend.* on .*ing = 658

intend.* .*ing = 10,384

So, of the total of both occurrences, 5.95 per cent are the non-standard, which surprised me…until I looked at the next two corpora.

Oxford New Monitor Corpus (April 2018; 7 billion 980 million words, 9 billion 286 million tokens)intend.* on .*ing = 4,926 = 48.1 per cent. Even more of a shock!

intend.* .*ing = 5,315

Well, that certainly changes the picture and helps explain how the French speaker mentioned earlier was told intend on +-ING was correct – by a teacher, to boot.

Brigham Young Corpus of Web-Based English(A measly 1.9 billion words from 20 countries)

These results are not dissimilar to the previous, shock, horror!

intend.* on .*ing = 606 or 42.85 per cent

intend.* .*ing = 858

Looking at the raw figures for US/Canada/UK gives us the following:

intend.* on .*ing 122 | 55 | 105

intend.* .*ing 41 | 10 | 172

In other words, in this corpus, US and Canadian speakers PREFER intend on +-ING.

At this point, it’s time to give up. Open the gates to the barbarians and welcome them in. Give them alot [sic] to eat and drink…in fact, a feast, a banquet, a surfeit. Reassure them that whatever twisted utterance they come out with is perfectly correct. I jest, of course—somewhat.

No doubt it won’t be too long before ‘the dictionaries’ record this and give it the green light.

As a footnote, in a poll on Twitter in which I asked if people (when editing) would change intend on keeping, 30 per cent said they wouldn’t. Which doesn’t, of course, tell me why they wouldn’t. Except that one person told me it’s ‘colloquial and common’ in the US.