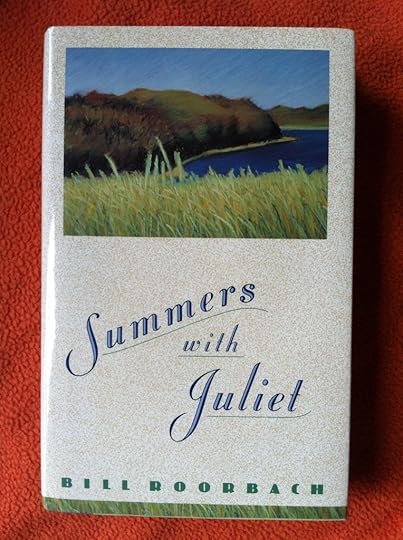

SUMMERS WITH JULIET is Twenty

Summers with Juliet, published February, 1992

Summers With Juliet started as an idea for a personal essay, one of my first ever (before that I'd only written formal essays and fiction), nothing more than this: My not-yet wife and I had seen an enormous fish in Menemsha Pond, Martha's Vineyard, a sea sunfish, Mola Mola. One January day I started to write that story, and by late March, I finished it. After a year of revising and enriching the thing (while writing other stuff, of course), I sent the essay off in the mail. The Iowa Review published it, and "Mola Mola'' eventually got an honorable mention in The Best American Essays, 1991.

Well, hey. I decided I was on to something, and wrote another piece—I considered what I was doing nature writing—about a great blue heron. Then another, about some blue crabs. My grad-school friend Betsy Lerner read them, kindly, and said the thing she liked best about them wasn't nature so much as that Juliet was there in all of them. Men usually left their women out of their nature writing. She thought there was a book in there. She even had a title for me: Summers with Juliet. And then she helped me connect with a great agent. Later, much later, she became my agent, but that's another story.

So: a collection of nature essays in which Juliet played a role.

Juliet now, with a new character

My new agent–Binky Urban at ICM–asked for a couple more and an annotated table of contents to describe the unwritten ones. She gave me ten days to do this. She was testing me. I did what she asked. She like one of the new pieces, tossed the other, formed a proposal, messengered it to ten or so top editors and sold the book on the second day out, to Houghton Mifflin.

I was kind of happy. Then I had to do the work. It took a year.

When I'd finished the seventeen essays that made the first draft of the book, everyone said to tie them together. And gradually, that's how the structure of Summers With Juliet emerged. That structure is self-consciously classical: three acts—situation, development, denouement (this last is from the French, as you know, for untying).

Act one comprises six scenes (I should say "scenes,'' since each is a chapter in itself, and some freestanding essays): "Hot Tin Roof,'' "Berkshire Turkeys,'' "Cross Canada,'' "Volcano,'' "Bluefishing,'' "Turtles.'' The situation: a callow young man (myself) in love with a young woman not impressed. A romance develops despite obstacles, mostly of the young man's making. The last scene ("Turtles'') ends with his realization that his own growth is required, and the arc of the narrative rises to act two.

In act two, which is comprised of "Out of the Frying Pan,'' "Hummingbirds,'' "Callinectes Sapidus,'' "Mola Mola,'' "Fishing With Bobby,'' and "Canyonlands,'' the situation (the romance) is developed in a series of tableaux, each built around a carefully nested central metaphor, each metaphor growing nearly absurd (especially when said directly, as will follow): Juliet is a wild trout in an unfished stream; Juliet is a bossy bird; Juliet is an elegant crab; Juliet is an ungainly and rare fish of enormous proportions; Juliet is a gawky heron; Juliet is dangerous as a snake and as big as the canyons of Utah. Or perhaps the word love should replace the name Juliet above: Act two has grand pretensions. Ends with our boy's resolve to marry.

Juliet in 1982, Martha's Vineyard, Age 20

Now, while I was about knitting my various essays together into a book (we'll get to act three in a minute), I realized that Summers With Juliet was doing something subversive: standing up to the boys from the cult of the expert and messing up the central mode of a traditional form—Nature Writing (yes, so self-important is the form that it must be capitalized). Which central mode is that a man goes alone into the wilderness and finds transcendence, glory, absolution, expertise, and so forth. As the central figure in his own autobiography, he finds his way to nothing less than him-ness (or Him-ness, if he gets to God, which is the Emersonian model). It's a male figure made countlessly by male practitioners over centuries, a particularly American figure: I faced the wilderness alone, made peace with it, and in that way conquered.

Bill that same summer (too much sun)... Going on 29

All I really had to do to subvert was to introduce a woman. And make her and her feminine contempt for the rites of the male my foil and my catalyst (because they were in life). To end the book with a wedding was to complete the subversion: Male autobiographies have not, historically, ended with weddings.

Act three, our conclusion: "Water,'' "Visitors,'' "River of Promise,'' "Bachelor Party,'' "A Wedding on the Water.'' The situation having been developed to an almost ecstatic height, our narrative arc begins its fall. The young man, now well feathered, bathes his beloved in an act of devotion, struggles with fear (again the trope is at work, everything to be read as an examination of love with its subtext of mortality), climbs a mountain to ask for her hand, goes fishing with his best man in Central Park (a reprise, a look back, a caesura), then is wed.

The book was published in February, 1992. I can hardly believe it has been twenty years. But it has.

Juliet and I met in July, 1982. Thirty years this summer. She was twenty.