I've been working more on Alice in Wonderland and Philosophy, and I got to a statement that made me shake my head:

Consider that the whole Wonderland story itself is one huge dream, since Alice's sister wakes her up for tea at the end. Alice never really visited an actual place called Wonderland; she just thought she did. –Robert Arp

Um. No.

When you are dealing with ideas rather than facts, you have to take into consideration that the rules for ideas do not match the rules for facts–and it's often useful to be aware that what we normally think of as "facts" are so moderated by ideas that the rules for facts may not apply. For example: "This sweater is red." However, if you look at a red sweater under a green light, it's black; our perception skews the color. Is the sweater "really" black or red? Color is reflected light: so it really depends on the color of light it's reflecting, doesn't it? It isn't "really" red or "really" black–it's just that most of the light we use would tend to show it as red. Practically speaking? Red. But in "reality," it's not red, because you can't define "reality" as "only in broad daylight," which is the only time it's really the red that we expect to see. Painters know this.

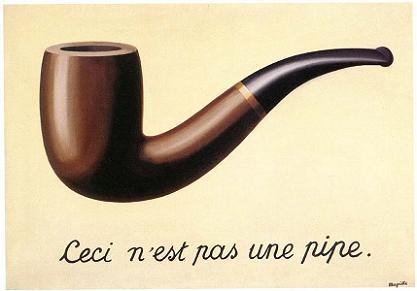

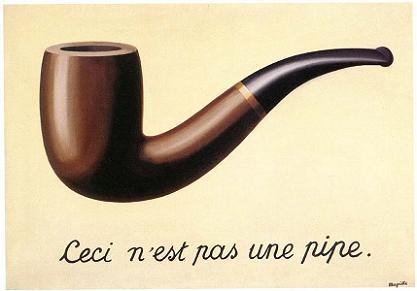

Is this a pipe or isn't it?

It is a pipe, and it is not a pipe. Opposite facts may not be true, but opposite ideas are often true. Love is the best…love is the worst. Bacon is good…bacon is bad. Death is tragic…death is hilarious.

Did Alice go to Wonderland, or did she dream it?

It's perfectly acceptable, when dealing with ideas, to be inconsistent. Even paradoxical. Because often the opposite "truths" of an idea are both true. Alice both did and did not go to Wonderland: it's a story. The characters in Wonderland are both logical and illogical. Words both have meaning that cannot be changed and are whatever we make of them (Humpty). We can believe six impossible things before breakfast (White Queen) and in order to reach our destinations, we often have to walk away from them (Red Queen). The Wonderland of the first book both is and is not the Wonderland of the second; the Red King both does and does not dream Alice into being. A pun is both logical and illogical; it both follows the rules and breaks them.

We think, "The opposite of something true is false," but it's very hard for an idea to be true, that is, factual. Because ideas are things we think and not facts, it's very easy for the opposite of an idea to be another idea, rather than just untrue. Yet we behave as though our ideas were facts: the opposite of me is other; the opposite of my point of view is bullshit. Yet many points of view have utility–even contradictory ones. Overall, it seems to take many different types of people (with correspondingly different points of view) in order to make things work. We can't all be pawns, after all, or deuces of spades, or even all chessmen, or even all gamesplayers–who will make the chessboards? Who will sell them? Yet we think that people who aren't like us, or who don't think like us, are liars, stupid, foolish, ignorant, and even inhuman. The pattern of thinking "the opposite of true is false" is a limitation, a hindrance–a poor tool.

The more valuable pattern, I think, would be not to teach a girl of ten or eighteen (when the books were written, relative to Alice Liddell's age) that there is one best strategy to follow through life–for example, logic–but to teach her that no matter what people say, no matter that one minute they're doing you "good" and another doing you "harm," no matter what changes you go through, there's a you there, and there are many tools (including but not limited to logic) that you can use to navigate even the most absurd of situations, including breaking rules (even logical ones). Many children find the Alice books perfectly terrifying–and they are. They poke holes in what we think of as real, right down to the level of "truth."

The fictional Alice can enter Wonderland through a rabbit-hole and exit it through a dream: it's a story, which are both real things and dreams, and something else besides.

newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Excellent riposte! His statement makes Alice in Wonderland sound like a simple story; your post a meaty, engaging book.

Excellent riposte! His statement makes Alice in Wonderland sound like a simple story; your post a meaty, engaging book.