Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 7: The Mage Arc

The final two archetypal character arcs in the life cycle deal primarily with questions of Mortality—and thus inevitably with the ultimate questions about the meaning of life.

The final two archetypal character arcs in the life cycle deal primarily with questions of Mortality—and thus inevitably with the ultimate questions about the meaning of life.

Throughout this series, we’ve viewed the six “life arcs” as part of a unified story structure, or Three Acts. The First Act—featuring the Maiden and the Hero—focused on overcoming challenges of Fear in integrating the parts of oneself and individuating. The Second Act—the Queen and the King—focused on challenges of Power and on integration within relationship to others. Finally, the Third Act—the Crone and the Mage—turns its attention to Mortality and to the integration of soul and spirit.

As we discussed in last week’s post, the Crone Arc represented the complete transition of the character from the “outer” world struggles with one’s self and other people into the “inner” world struggles with more existential and spiritual crises. Although anyone who lives long enough will reach the Crone Arc at least chronologically, not everyone will accept her challenge and fulfill her difficult arc of embracing her own mortality. Therefore, even fewer among us will even get the opportunity to truly take on the deep mysteries of the powerful Mage Arc.

In part because of that fact itself, the Mage Arc is mysterious. We see it most plainly in the metaphor of fantasy stories that offer up a supernatural Mentor to a world in need. But rarely is this character the protagonist (perhaps because almost all of us relate more obviously to the younger archetypes who mirror our own positions in the cycle). Even more rarely is the Mage fully embodied in a “realistic” story (although to my mind Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird seems a possible example from a symbolic viewpoint).

Even when the Mage shows up in a real-world story, his deep, almost otherworldly wisdom inevitably brings with it a touch of the magical—as, for example, with Will Smith’s wise and mysterious caddy in the golf movie The Legend of Bagger Vance.

Sacred Contracts by Caroline Myss (affiliate link)

In Sacred Contracts, Caroline Myss notes:

The … Magician produce[s] results outside the ordinary rules of life….

This doesn’t necessarily mean the character is magical in any way. But it does mean the character has not only glimpsed but assimilated truths about life that most people don’t even know exist. By accepting his own mortality back in the Crone Arc, he has now reached a new level of transformation, objectivity, and wisdom.

Women Who Run With the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estes (affiliate link)

In Women Who Run With the Wolves, Clarissa Pinkola Estés speaks to this archetypal wisdom:

The mage, or magician [is] whom the king brings with him to interpret what he sees…. Such things as the split-second recall, the thousand-league vision, the hearing over miles, the empathic ability to see from behind anyone’s eyes—human or animal— … the magician … shares in these and also, traditionally, helps to maintain them and enact them in the outer world. Though the mage can be of either gender, here it is a powerful male figure similar in fairy tales to the stalwart brother who so loves his sister that he will do all to help her. The mage always has crossover potential. In dreams and in tales, he appears as a man as often as he shows up as a woman. He can be male, female, animal, or mineral, just as the crone, his female counterpart, can also affect her guises with ease.

For the Mage, who has already accepted Death, what is there left to transform? What is left, of course, is the final threshold to cross in earnest. But there is also the final temptation—to use his great power and wisdom, the riches of his entire well-spent life, not to guide those he loves but to control them in ways he has no right to. Will he surrender—or become Sorcerer?

Reminders: Once again, before we officially get started, I want to emphasize two important reminders that hold true for all of the arcs we’ve studied.

1. The arcs are alternately characterized as feminine and masculine. Primarily, this indicates the ebb and flow between integration and individuation, among other qualities. Together, all six life arcs create a progression that can be found in any human life (provided we complete our early arcs in order to reach the later arcs with a proper foundation). In short, although I will use feminine pronouns for the feminine arcs and masculine pronouns for the masculine arcs, the protagonist of these stories can be of any gender.

2. Because these archetypes represent Positive-Change Arcs, they are therefore primarily about change. The archetype in which the protagonist begins the story will not be the archetype in which he ends the story. He will have arced into the subsequent archetype. The Mage Arc, therefore, is not about becoming the Mage archetype, but rather arcing out of it into the beginnings of what I’m calling “the Saint” archetype—but basically just indicating his final ascension into a “good death.”

The Mage Arc: Joining GodAlthough the Mage can be played by a younger character, the arc itself is representative of the final chapter of one’s life. The Mage represents a person who has successively and positively completed all six life arcs. This is, in fact, an unusual and extraordinary achievement. Merely reaching the end of our lives doesn’t mean we’ll get to go out as Mages. The Mage, then, is someone who put in an unfailing amount of work throughout his life, someone who has consistently sought light and truth—and been rewarded in that search.

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell (affiliate link)

And now he has almost reached the end. Not only is the end of his life on earth incumbent because of his great age, but he has transcended many of the challenges that weigh us down in our earlier acts. In The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell speaks of this stage:

The ego is burnt out. Like a dead leaf in the breeze, the body continues to move about the earth, but the soul has dissolved already in the ocean of bliss.

But however wise the Mage may be, he is still a body on this earth, and he has not yet surrendered everything. There remain things he cares about, causes in which he passionately believes. And however burnt out the ego may be, there is still a flickering spark. He has the ability and the insight to not just guide those who come behind him, but to shape and even control certain outcomes. How he uses his power and how ready he is to truly shed the things of this world and step willingly into death will be the mark of his final successful arc.

Stakes: Leaving Behind Good World for Those to FollowAs with all good stories, life has a tendency to come full circle. Grandparents often become increasingly focused on the “legacy” they will leave to their beloved descendants. Physically, they sometimes even return to the very same hearth at which they themselves leaned on their own grandparents’ knees, hearing stories of adventures long past.

It is no wonder we most prominently find the Mage in his Flat-Arc form of Mentor. The deeper we get into the life arcs, the more frequently we see previous archetypes showing up in some version of their own stories. And so the Mage Arc inevitably runs concurrently with the younger arcs, particularly those of Hero and King. The Mage is the wise voice in their ear, initiating them and guiding them to see what they have not yet the maturity or the experience to see for themselves.

The Mage cares deeply about whether these younger characters will fulfill their arcs. Will they be able to face the same challenges he did? Will they overcome? How will they be able to resist the temptations of sloth and power present in their counter-archetypes if the Mage does not take care to protect them from themselves?

The Mage’s challenge is very much represented in the anecdote about the boy who waited and waited for his caterpillar to emerge from its cocoon. When the time came and he witnessed how terribly the butterfly struggled to free itself, he “helped” by clipping open the cocoon. He did not realize the butterfly’s struggle out of the tight cocoon was what forced the blood into its beautiful wings. This butterfly emerged with its wings impossibly swollen and limp—and, to the boy’s chagrin, it died.

The Mage, who holds so much power to shape the lives of those he loves, faces the primary challenge of letting them go. He must let them face their own struggles and make their own mistakes. Not only is this crucial to the continuance of healthy life-arc cycles after him, it is also his final challenge in shedding his remaining burdens of this world—and stepping freely into the next.

Antagonist: Understanding the Nature of EvilWithin the Mage’s story, the external conflict may be represented by relatively mundane threats. This is because what now threatens the Kingdom is necessarily a threat “of this world” and rightly pertaining, in fact, to the conflicts of earlier arcs. The Kingdom is under dire threat—perhaps by the Hero’s Dragon, the Queen’s Invaders, or the King’s Cataclysm—but that threat will ultimately be faced by the younger archetypes. The Mage is there to help them understand their duties, but more than that, he is there to combat an even more archetypal antagonist the others cannot yet see.

Campbell puts it:

They fight the demons so that others can hunt the prey and in general fight reality.

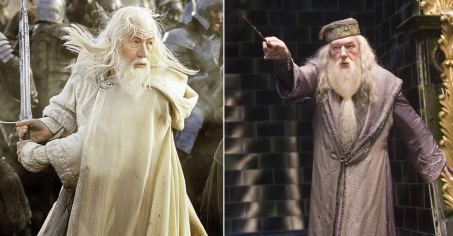

This can be seen in the beautiful fantasy stories of The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter, both of which feature Mentor/Mage characters—Gandalf the White and Dumbledore, respectively—who use their power against a much greater evil, while also guiding the younger archetypes as they take on more corporeal antagonists.

However epic the stakes may (or may not) be in the story’s external conflict, the Mage’s story is ultimately one of tying off loose ends and ending the tale. It is about ending one’s life well and dying a good death. Campbell references this finale in a quote from Dante Alighieri’s spiritually metaphoric poem The Inferno:

So it is that when Dante had taken the last step in his spiritual adventure, and came before the ultimate symbolic vision of the Triune God in the Celestial Rose, he had still one more illumination to experience, even beyond the forms of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. “Bernard,” he writes, “made a sign to me, and smiled, that I should look upward; but I was already, of myself, such as he wished; for my sight, becoming pure, was entering more and more, through the radiance of the lofty Light which in Itself is true. Thenceforward my vision was greater than our speech, which yields to such a sight, and the memory yields to such excess.”

The Mage need not literally die in your story (especially if he is represented by a younger character). But he will almost certainly journey on in some respect, even if it is just walking off into the sunset like Bagger Vance (or, in a more symbolic version, Galadriel’s “diminishing into the West” after resisting the final temptation of the Ring’s power).

If he does die, the death may either be a voluntary choice in some sense (such as Obi-Wan Kenobi’s sacrificing himself to Darth Vader in A New Hope or Dumbledore’s plot with Snape in The Half-Blood Prince) or at least a death to which he goes without regret or reluctance (as does Yoda in Return of the Jedi and Garth and Hub McCann in Secondhand Lions). He represents someone “who has fought the good fight and finished his race.”

For easy reference and comparison, here are some scannable summations of the arc’s key points:

Mage’s Story: A Mission.

Mage Arc: Sage to Saint (Liminal World to Yonder World)

Mage’s Symbolic Setting: Cosmos

Mage’s Lie vs. Truth: Attachment vs. Transcendence

“My love must protect others from the difficult journey of life.” versus “True love is transcendent and allows life to unfold.”

Spiral Dynamics by Don Edward Beck and Christopher C. Cowan (affiliate link)

Mage’s Initial Motto: “I, the knowing.”

(This is via Spiral Dynamics’ “Yellow” Meme. If you’re not familiar with Spiral Dynamics, this probably won’t mean anything, but I was fascinated to realize that the six positive archetypal arcs line up perfectly with the “memes” of human development as found in the theory of Spiral Dynamics.)

Mage’s Archetypal Antagonist: Evil

Mage ’ s Relationship to Own Negative Shadow Archetypes:

Either Miser finally opens himself up through his Wisdom to gain Transcendence.

Or Sorcerer learns to surrender his worldly wisdom in exchange for true Transcendence.

The Beats of the Mage Character ArcFollowing are the structural beats of the Mage Arc. Even more than ever for this arc, I am using allegorical language (in keeping with the tradition of the Hero’s Journey). However, it is important to remember the language is merely symbolic. None of the archetypes or settings need to be interpreted literally.

This is merely a general structure that can be used to recognize and strengthen Mage Arcs in any type of story. Although I have interpreted the Mage Arc through the beats of classic story structure, it doesn’t necessarily have to line up this perfectly. A story can be a Mage Arc without presenting all of these beats in exactly this order.

1st ACT: Liminal WorldBeginning: Powerful But Limited

The Mage is an enlightened person—-someone who has understood and accepted the vast and paradoxical partnership of Life and Death. He walks the Liminal World—an existence that is neither Life nor Death but between them. He has no particular home, but roves the land, moving from problem spot to problem spot, helping resolve magical hang-ups or simply solve disputes via his otherworldly wisdom.

He is greatly revered and loved, seen by some as an avuncular friend and by others as a fearsome mystical force. He loves others, but really he loves all—living in a calm neutrality that sees the greater purposes at work in Life’s systems.

He is a friend of Death—but not of Evil, which he has learned to distinguish as not Death itself but the death urge or the addiction to power (being the power over Life and Death). As such, he is careful of his own power, recognizing himself not as a master but as a servant. In overcoming his fear of Death, he has also largely transcended his ego.

In The Legend of Bagger Vance, the mysterious caddy and golf expert shows up, seemingly out of nowhere, seemingly in need of a job—from the one person who most needs his help.

Inciting Event: Revelation/Rise of Evil

At one of the stops along his pilgrimage, the Mage learns of “a disturbance in the Force.” He learns Evil has returned or is lurking, waiting for the alignment of events. The Mage is deeply disturbed, not only because he stands opposed to Evil, but because he fears for the suffering and misguidance that may be inflicted on the Kingdom and its children, whom he loves.

He may here encourage a Hero to help him, either to hold the fort while he’s gone or to accompany him on his mission to seek out the source of this threat of Evil and hopefully cut it off at the pass. But the Hero dawdles, and the Mage must start the action on his own.

In The Miracle on 34th Street, Kris Kringle agrees to take a job as Santa Claus in Macy’s Department Store when he realizes the true spirit of Christmas has been forgotten amidst all the commercialism and cynicism.

2ND ACT: Yonder WorldFirst Plot Point: Climbs the Mountain

The Mage climbs the Mountain, bravely ascending to the Yonder World because only he has the power and insight to do so. He is allowed to understand the full threat of the Evil.

He may confront a Sorcerer corrupted into a conduit for Evil, or he may witness Evil itself. He may wrestle with his own dilemma, fighting against the need to surrender and the idea that true love is transcendent.

The Hero may accompany him or may go off on his own Quest. He is unlikely to ascend the Mountain with the Mage, but if he does, he will not see the full extent of the supernatural that the Mage does.

In The Ten Commandments, Moses ascends Mt. Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments from God. (He leaves his protege Joshua halfway up.)

First Pinch Point: Evil Infiltrates the Camp of Man

The courage of man begins to fail. In the face of the great Evil, some waver in their goodness when confronted by their fear of Death. Compromises and deals with the devil are made. The Hero is abused for his efforts and also tempted from his path. The Mage returns to scold and advise the people of the Kingdom. Even in his profound wisdom, he is deeply invested in their fate. He doesn’t want them to suffer or to choose the wrong path. He mentors them.

In To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus insists his son Jem spend a month reading to a crotchety old lady after Jem destroyed her flowers in a fit of rage.

Midpoint: Confronting Evil—and Also Evil in the Heart of Man

The Mage loves his world and his people. He wants to help them as a good Father/Grandfather should. But he is beginning to realize he cannot help them. They must help themselves. In a great battle or time of need, he may confront Evil itself to clear a path for them (to help keep it a “fair fight”), but he cannot defeat the evil inclinations in their own hearts. He can only stand by and wait—and hope.

But even his hope is a source of inner conflict. He is caught between the urge to save them and the need to access the surrendered love of detachment.

Thanks in part to the Mage’s intervention (and also his counsel), the Kingdom escapes destruction even though it may be defeated in this battle. The Hero rallies to his true identity and strength, in no small part because his love for the Mage causes him to want the Mage to be proud of him and pleased by his efforts.

In Mary Poppins, Mary maneuvers the children’s neglectful father into taking them with him to his job at the bank.

Second Pinch Point: Heart Is Broken by Man ’s Suffering

Man is betrayed by Man. The Hero is in bad straits, broken, doubting, suffering. The Mage is deeply wounded by his love for them all. He is challenged in his growing realization that true Love is transcendent and cannot make choices for others in order to protect them from their own mistakes. The Mage comforts the Hero and others but hasn’t much else to offer. He rages within himself, struggling and angry that it should be so.

In Miracle on 34th Street, Kris is incensed when he hears that his young ward who enjoys playing Santa Clause for younger children has been told by the store psychiatrist that something is wrong with this desire.

3rd ACTFalse Victory: Refuses to Interfere with Man ’s Choices—and Man Chooses Wrong

The Mage wins his inner battle and makes the hard choice to let the Kingdom dwellers, including his Hero, go forth and make exactly the wrong choice. There is tremendous fallout, but the Mage must stand back, seemingly callous, and watch, trusting that it is part of a bigger plan, which he is now coming into alignment with.

In Doctor Strange, the Ancient One allows herself to die.

Third Plot Point: Brink of Annihilation

The Kingdom faces death in the external conflict. The Mage, however, faces transformation—the choice to finally and fully step into the Yonder World (i.e., death).

In The Return of the Jedi, Yoda recognizes it is his time to return to the Force.

Climax: Meeting With the Divine

In the midst of his annihilation/transformation, the Mage is confronted by the Divine and is thus raised above the mortal world of men, including their limited insight and emotion. He will finish what he started as the Crone, this time literally leaving Death for Life.

Galadriel passes her final test of refusing the One Ring’s power, even though she knows it means she “will now diminish” and “pass into the West.”

Climactic Moment: Evil Redeemed/Destroyed

The Mage does not directly interfere in the great battle against Evil, but the Hero and others see him and are inspired to seek Good against Evil whatever the cost. He inspires them to seek Hope. Through his inspiration and their efforts, Evil is either redeemed or destroyed.

On the last hole, Bagger Vance steps back to let his student make his own decision about whether he will win the game by cheating.

Resolution: Kingdom Renewed for Another Cycle

The Mage says his goodbyes, engulfing the sorrow of his children in great love, as he prepares to journey on to the Heavens.

Mary Poppins leaves the Banks family, sad to go because she loves them but knowing it is best for them to make do on their own now.

Examples of the Mage Arc

For reasons already mentioned, I found it difficult to discover many examples of a Mage Arc undertaken by a protagonist, so many of the following examples include characters who are more properly “Mentors” in someone else’s story. Click on the links for available structural analyses.

Kris Kringle in The Miracle on 34th St.The Ancient One in Doctor Strange Yoda in Star Wars Alfred Pennyworth in BatmanGaladriel in The Lord of the Rings Gandalf the White in The Lord of the RingsGarth McCann in Secondhand Lions Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird The Oracle in The Matrix Mary Poppins in Mary Poppins Bagger Vance in The Legend of Bagger VanceStay Tuned: Next week, we will begin studying the Negative or Shadow Archetypes.

Related Posts:

Story Theory and the Quest for MeaningAn Introduction to Archetypal StoriesArchetypal Character Arcs: A New SeriesThe Maiden ArcThe Hero ArcThe Queen ArcThe King ArcThe Crone ArcWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you think of any further examples of stories that feature the Mage Arc? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 7: The Mage Arc appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.