Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 6: The Crone Arc

Within the saga of the six archetypal character arcs representing the cycle of human life, the two “elder” arcs that comprise the Third Act of life are perhaps the least dramatized. These arcs are those of the Crone and the Mage.

Within the saga of the six archetypal character arcs representing the cycle of human life, the two “elder” arcs that comprise the Third Act of life are perhaps the least dramatized. These arcs are those of the Crone and the Mage.

In studying these arcs, it becomes evident that the Third Act of story structure is, in itself, rather more mysterious than we give it credit for. In our modern storytelling, the Climax is meant not only to be the point, but also the most exciting moment in the story. But many views of story structure (not least the classic Hero’s Journey) instead emphasize the Midpoint as the most significant moment in the plot, with the Third Act acting as more of a resolution or summation.

Although that is a discussion for another time, it is interesting to acknowledge the parallels in this view of structure with that of human life itself. In many ways, a person’s Third Act is the “quietest” time of life. What happens within it is massively influenced by the choices that have come before in the previous two acts. Now we have only to see how everything pans out.

But this is, in many ways, only a surface view of the final act of life. If the Elders are no longer so embroiled in the challenges of survival and power that mark the earlier acts, they are no less involved in the final and in many ways the greatest challenge—the conundrum of a life that must end in death.

In our deeply death-averse Western culture, we have largely avoided stories about the Third Act of life. This is both cause and effect to the reality that just as our modern societies lack crucial initiations for the young (such as found in the Maiden and Hero Arcs), they also suffer from a dearth of true Elders—those who have completed all previous life arcs and are able to not only undertake their own final and most crucial arcs, but also to act as the archetypal Elders and Mentors who are so catalytic in the younger arcs.

In short, I believe these arcs are desperately important and under-served. It is, in fact, difficult to think of many suitable story examples. Most of the time when a Crone or a Mage shows up in a story (especially a popular or genre story), they appear as a supporting character within the arc of a younger protagonist.

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

The Crone Arc begins the final act of the “life arcs” by presenting an inevitable and imperative Underworld Journey. Just as the transition from Queen to King marked the Midpoint or Moment of Truth in the overarching saga, the transition from King to Crone signifies the Third Plot Point. And if you have studied story structure with me before, you already know the Third Plot Point is the doorway of Death and Rebirth.

…one night

here’s a heartbeat at the door.

Outside, a woman in the fog,

with hair of twigs and a dress of weed,

dripping green lake water.

She says, “I am you,

and I have a traveled a long distance.

Come with me, there is something I must show you…”

She turns to go, her cloak falls open,

Suddenly, golden light … everywhere, golden light….

—“Woman Who Lives Under the Lake” by C.P. Estes

Reminders: Once again, before we officially get started, I want to emphasize two important reminders that hold true for all of the arcs we are studying.

1. The arcs are alternately characterized as feminine and masculine. Primarily, this indicates the ebb and flow between integration and individuation, among other qualities. Together, all six life arcs create a progression that can be found in any human life (provided we complete our early arcs in order to reach the later arcs with a proper foundation). In short, although I will use feminine pronouns for the feminine arcs and masculine pronouns for the masculine arcs, the protagonist of these stories can be of any gender.

2. Because these archetypes represent Positive Change Arcs, they are therefore primarily about change. The archetype in which the protagonist begins the story will not be the archetype in which she ends the story. She will have arced into the subsequent archetype. The Crone Arc, therefore, is not about becoming the Crone archetype, but rather arcing out of it into the beginnings of the Mage Arc—and so on.

The Crone Arc: Facing Down DeathThe word “Crone” is a tricky one in some ways (although this seems appropriate to me because the Crone herself is a tricky one). The word conjures images of a hook-nosed hag with a hairy wart on her lip. Gone is all the beauty of youth, to the point that her visage is almost frightening. She lives alone, deep in the woods, discouraging contact with the curious and half-terrified children who seek her out to see if she is really the witch of local legend.

A popular figure in folk and fairy tales, she is often amoral, sometimes wreaking havoc on unwary villagers who dare trespass in her woods, sometimes offering surprising understanding and blessing—and usually the difference is decided by the worthiness of the intruder.

When we hear tell of the “Crone,” our response is often visceral and uncertain. But I have come to love the word, because the true Crone (and not her negative counter-archetypes of Hermit or Wicked Witch) is a portal to the deep wisdom of Elderhood. Her external beauty is vanished. Any temporal power or glory she won when she was the King archetype is long since abandoned. She gave it all, perhaps graciously but certainly not without heartbreak, in order to secure the Kingdom for her successors and journey on into the twilight.

In so many ways, the Crone archetype starts out broken. She who was once King is now fallen from all her power. No longer does she sit on a throne in the palace, but rather on a stool in a hut. No longer is she mighty, both physically and politically. Now, she withered and weathered, hunched with rheumatism.

She can seem like a bit of a crank at first, but really this is because the great leap from the Second Act of her life to the Third is a lot to process. She has retreated to the hut in the woods in order to integrate, to process, to lick her wounds, and to grieve. As all Third Plot Points do, hers has demanded the complete death of the person she was. Her challenge, then, is to decide whether she will now accept the call to be rebirthed.

Women Who Run With the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estes (affiliate link)

She doesn’t fully understand it yet, but in losing everything, she has in fact grown in something much greater. In speaking of the Baba Yaga tales of Eastern Europe, Clarissa Pinkola Estés says in Women Who Run With the Wolves:

If the Yaga is true to form, she would not care to be too close to, nor for too long near, the too conforming, too demure side of the feminine nature…. Although sweetness can fit into the wild, the wild cannot long fit into sweetness.

At the beginning of her arc, the Crone is an Elder already—old and wise and possessing some magic. But, for all that, she is not greatly powerful. She is resigned to Death but still afraid of it. She knows her uses but doesn’t find tremendous power in her life. Whether gracefully or not, she is just waiting to die. Therefore, hers is an arc from disempowerment to empowerment. Her “magic,” such as it is, evolves from little tricks (e.g., Gandalf the Grey’s fireworks) to great strength (e.g., Gandalf the White’s tremendous power—which can, in the Mage Arc turn sorcerous if not restrained with wisdom).

Sacred Contracts by Caroline Myss (affiliate link)

But this is not to say the Crone has forsaken the Kingdom entirely. Her call to emerge once more from her solitude of contemplation and self-healing is likely to arrive in the form of a young Maiden or Hero who needs her help. Carolyn Myss states in Sacred Contracts:

The Guide takes the role of Teacher to a spiritual level…. Wisdom comes with age, and so the Crone or Wise Woman represents the ripening of natural insight and the acceptance of what is, allowing one to pass that wisdom on to others.

This younger character will come to her as a messenger of sorts, summoning her from her solitude to confront the greatest enemy yet—a malignant evil—a superfluity of Death threatening the Kingdom. And she accepts the call, thinking to herself, I’m old, so oh well, if I die, I die. Estés describes the mindset that is the crucial challenge of the Third Act arcs’ overarching antagonist of Mortality:

Things of the world that used to be food for us lose their taste. Our goals no longer excite us. Our achievements no longer hold interest. Everywhere we look in the topside world, there is no food for us.

But the journey becomes much more—a soul-deep sacrifice in order to protect the realm of Life. She chooses Life—not just her own or anyone’s in particular, but Life itself—even though that will also means accepting Death in all its profundity.

Just as the King represented the sacrifice unto Death—the propitiating sacrifice to save the Kingdom—the Crone represents a Resurrection—the symbolic return of Life.

Antagonist: Paying a Penny to the FerrymanThe adversary the Crone faces is Death made manifest. Within the plot, this antagonist may be externally represented as a Death Blight upon the Kingdom. This is not “natural” Death, but Death run rampant, Death that is out of balance with Life and overpowering it. More literally, however, this symbolism is merely the representative of the human being’s need to reconcile with her own mortality. The Crone story may be as fantastic as that of Gandalf’s descent into Khazad Dum or as realistic as the quiet struggle with incumbent old age as in Robert Redford and Jane Fonda’s Our Souls at Night.

It can also be seen in the quiet isolation of characters such as Marilla Cuthbert at the beginning of Anne of Green Gables.

There is even a bit of the Crone in Taika Waititi’s tale of the orphan boy and his extremely cranky and unwilling foster father in Hunt for the Wilderpeople.

Whether symbolically to at least some degree or utterly realistically, the Crone’s journey is a descent into the Underworld. She pays her penny to the ferryman, crosses the River Styx, and goes to give Death a good talking to—while hopefully keeping her headstrong young charge from doing anything too stupid.

Walking on Water by Madeleine L’Engle (affiliate link)

It’s a tale that has fully as much scope for hilarity as for heaviness. But it is fundamentally a heavy theme—a confrontation with the final antagonist against whom all humans instinctively struggle and, if the arc completes, a recognition that Death may not have been what we always believed. In Walking on Water, Madeleine L’Engle muses:

…this land of death is dark and frightening. No matter how deep the faith, we each have to walk the lonesome valley; we each have to walk it all alone. The world tempts us to draw back, tempts us to believe we will not have to take this test. We are tempted to try to avoid not only our own suffering but also that of our fellow human beings, the suffering of the world, which is part of our own suffering. But if we draw back from it (and we are free to do so), Kafka reminds us that “it may be that this very holding back is the one evil you could have avoided.”

The Virgin’s Promise by Kim Hudson (affiliate link)

In The Virgin’s Promise, Kim Hudson speaks of the Maiden’s Third Plot Point beat as “Wandering in the Wilderness.” I love this term not just for the Maiden but as an emotionally resonant description of all Third Plot Point experiences, including the entirety of the Crone Arc itself.

Estés describes this “wandering in the wilderness” thus:

Theme: Choosing Descent and Return

Women in this stage often begin to feel both desperate and adamant to go on this inward journey, no matter what. And so they do, as they leave one life for another, or one stage of life for another, or sometimes even one lover for no other lover than themselves. Progressing from adolescence to young womanhood, or from married woman to spinster, or from mid-age to older, crossing over the crone line, setting out wounded but with one’s own new value system—that is death and resurgence. Leaving a relationship or the home of one’s parents, leaving behind outmoded values, becoming one’s own person, and sometimes, driving deep into the wildlands because one just must, all these are the fortune of the descent.

So off we go down into a different light, under a different sky, with unfamiliar ground beneath our boots. And yet we go vulnerably, for we have no grasping, no holding on to, no clinging to, no knowing—for we have no hands.

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell (affiliate link)

The Crone’s journey is perhaps the most terrifying of all the arcs. But at the nadir of her descent, there is the opportunity for the greatest riches of all. In The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell describes this Third Plot Point state:

The adventure of the hero represents the moment in his life when he achieved illumination—the nuclear moment when, while still alive, he found and opened the road to the light beyond the dark walls of our living death.

In the end, the Crone’s true transformation is not the decision to Die, as it was for the King. Rather, her crucial decision is to Live again—to rise up and leave the Underworld rather than accept the temptation of old age’s slow, resigned, comfortable descent into Nothing. In so rising, she symbolically raises the entire Kingdom with her—if not directly at least by revealing the possibility and the way. She goes to Death seeking an enemy, but in the end is surprised to find, if not a friend, then at least not an enemy.

Estés:

…the descent will nourish even though it is dark, even though one feels one has lost one’s way. Even in the midst of not knowing, not seeing, “wandering blind,” there is a “Something,” an inordinately present “Someone” who keeps pace.

The Crone’s Moment of Truth brings the revelation that she can “seek ye this day Life and not Death.” But not until the end of her story, when she fully rejects the Lie that Death is something to be defeated rather than embraced will she comprehend that indeed Death is Life—and become the Mage.

Key Points of the Crone ArcFor easy reference and comparison, I will be sharing some scannable summations of each arc’s key points:

Crone’s Story: A Pilgrimage.

Crone Arc: Elder to Sage (Uncanny World to Underworld)

Crone’s Symbolic Setting: Underworld

Crone’s Lie vs. Truth: Death vs. Life

“All life ends in death.” versus “Life is Death and Death is Life.”

Crone’s Initial Motto: “We, the accepting.”

Spiral Dynamics by Don Edward Beck and Christopher C. Cowan (affiliate link)

(This is via Spiral Dynamics’ “Green” Meme. If you’re not familiar with Spiral Dynamics, this probably won’t mean anything, but I was fascinated to realize that the six positive archetypal arcs line up perfectly with the “memes” of human development as found in the theory of Spiral Dynamics.)

Crone’s Archetypal Antagonist: Death Blight

Crone ’ s Relationship to Own Negative Shadow Archetypes:

Either Hermit finally accepts her Perception in order to grow into Wisdom.

Or Wicked Witch learns to submit her Perception to the truths of greater Wisdom.

Crone’s Relationship to Subsequent Shadow Archetypes as Represented by Other Characters:

Invigorates Miser or destroys Sorcerer through her wisdom.

The Beats of the Crone Character ArcFollowing are the structural beats of the Crone Arc. I am using allegorical language in keeping with the tradition of the Hero’s Journey (and honestly because it’s so powerful). However, it is important to remember that the language is merely symbolic. Although in this case the Crone usually will be an older person in some sense, none of the other mentioned archetypes or settings need to be interpreted literally.

This is merely a general structure that can be used to recognize and strengthen Crone Arcs in any type of story. Although I have interpreted the Crone Arc through the beats of classic story structure, it doesn’t necessarily have to line up this perfectly. A story can be a Crone Arc without presenting all of these beats in exactly this order.

As with all of the archetypes, the Crone can manifest within anyone’s life at any time, on a smaller scale. For example, any time a younger person faces as existential crisis—such as a mid-life crisis—they are very likely undergoing a Crone “subplot” as part of one of their larger arcs (i.e., because the Crone represents the Third Plot Point, she is always present, in some capacity, at the Third Plot Point of any of the previous arcs).

1st ACT: Uncanny WorldBeginning: Lure of Retirement

The Crone lives alone in a hut on the edge of the village. She is retired from public life and service, and although her former subjects may approach her for guidance as an Elder, she does not particularly encourage it. She is grumpy, worn, and hobbled by old age.

However, in completing the previous King Arc and crossing the last threshold into her Third Act, she broadened her understanding of the world beyond that of the temporal and into an acceptance of a greater spiritual realm. She works within that realm, making remedies and tinctures for herself and for those who might dare to ask for her help.

She’s not exactly misanthropic, but she is deeply introverted, processing her transformation from King to Crone, from youth and power to old age and numinousness. She’s retired. She’s not entirely happy about it, but she has accepted it as unavoidable.

Nevertheless, that acceptance has nudged her in the direction of lethargy. Even as she mourns the end of her youthful Second Act, she also feels like she’s earned her retirement. She’s old and tired; she’s accomplished more in her life than she ever knew possible. Rather than properly mourn her mortality and transform, she is tempted to just lie down and give up until Death comes to take her.

In the beginning of Anne of Green Gables, Marilla Cuthbert is a sullen, unhappy woman who doesn’t even realize how she has cut herself off from life.

Inciting Event: The Dream of Death

The Crone dreams a premonition about an imbalance in the Life and Death Forces. Death is coming to blight the land—either directly through a pestilence or apocalyptic event or indirectly through some sort of death culture. The choice to live and be alive is about to become very challenging for the world.

The Kingdom may be experiencing its first hint of this coming Blight. Most of the world will not recognize it for what it is (some even championing its advent) because they lack the spiritual insight of an Elder to discern its true malignant nature.

A Hero or King may come to the Crone seeking guidance (although not really understanding what it is they truly seek). She is resistant to rejoining the struggles of the larger Kingdom. She might give them a hint of the truth, but she shoos them away, not wanting to be bothered—even though her heart is heavy with her own fear of Death.

In The Fellowship of the Ring, Gandalf the Grey begins to suspect the true malignant nature of Bilbo’s ring after Frodo inherits it.

2ND ACT: UnderworldFirst Plot Point: Boards the Ferry

The Crone is drawn out from the retirement of her hut, perhaps by her Hero apprentice, perhaps by the entreaty of the King, or perhaps by a sign in her dreams. Grumpily, she agrees to go investigate, even though she still thinks it’s a waste of time. Who can defeat Death, after all? Certainly, not her—in all her feebleness.

But whether she admits it or not, hope sparks in her heart—maybe Death can be defeated. Her resignation also leads her to accept that, since she is old and about to die anyway, she might as well see about doing one more good turn for “the grandchildren.” Her love, symbolic or actual, for the Hero might be what finally prompts her to go forth to the River Styx and wait for the Ferryman. She leaves behind the Kingdom and enters the Underworld, where she intends to see what this is all about and to try whatever tricks she may to delay Death.

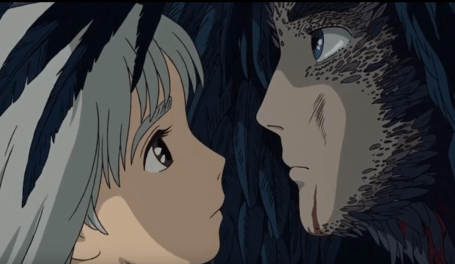

In Howl’s Moving Castle (which is a brilliant Crone-Arc-within-a-Maiden-Arc), Grandma Sophie treks into the Waste to try to regain her youth, enters Howl’s Moving Castle, and ends up involved in freeing the Kingdom from a malignant war.

First Pinch Point: Death Is Not Fooled by Her Little Tricks

In the Underworld, the Crone hobbles along, presenting (and mostly believing) herself as a harmless, helpless old woman. But she proves herself canny. Her small magic tricks, such as they are, help her past her various obstacles on her way to discovering the source of the Death Blight.

But Death is not fooled, and neither is the Sorcerer/Miser (if there is a human antagonist causing the Blight). Emboldened by her success thus far, she tries one trick too many and is thwarted by a discovery of her true weakness. She is startled, because the weakness proves to be one of insight and perception rather than the physical weaknesses she has identified with. She becomes even more frightened to a certain degree, but she is also intrigued: her understanding is broadening; she has glimpsed the true power available to her.

In The Hunt for the Wilderpeople, Hec learns he is wanted by the authorities for “kidnapping” his foster son (who, in fact, he has thus far desperately wanted to get shed of).

Midpoint: Chooses to Seek Life

As the Death Blight descends upon the Kingdom, the Crone must make a choice: will she give up and return to her hut (or allow herself to simply be overtaken by nullity)? Or will she find the strength, courage, and liveliness to rise again, but in a new capacity—not a King and not a Crone, but the beginnings of a Mage?

She chooses Life, even though at this point that means fully facing her fear of Death. She chooses to rise up and stand against the Blight. She uses all her wily tricks to resist it. The Sorcerer is startled, both that she dares to present herself as an antagonist and also that she has the power to make any kind of dent. He does not take her as a serious threat, but he does fully notice her as a spiritual power in her own right. He mostly wins the battle, but thanks to her choice, he is at least forced to pull back for a moment to reconsider his next move.

In Secondhand Lions, Hub proves that “old age and treachery will always beat youth and exuberance” when he handily defeats a group of young bullies.

Second Pinch Point: Temptation

The Crone may guide the Hero, the Queen, and the King in erecting defenses. But she stands apart from the true struggle, working her magic behind the scenes, discovering her true Life power. She is confronted—perhaps in the guise of the evil Sorcerer or perhaps by the neutral Death force—with a temptation. Now that she has chosen Life over Death, she becomes even more determined to live and not die.

The tempter offers that she might become immortal: Death will never touch her. She intuits there is a great danger to this supposed gift, even though she does not yet fully grasp the truth that Death is Life and Life is Death. She does, however, understand that Death is important—that however it may frighten her, its sheer necessity means it cannot be a wholly malignant force. She also inherently mistrusts the tempter, even as he promises that she will gain such power from this choice that she can save the Kingdom and stop Death (essentially becoming the Sorcerer). She doesn’t partake of the fruit and sends away the messenger, but she keeps the apple in her pocket—undecided about her proper course.

In Iron Lady, an elderly Margaret Thatcher (suffering from dementia) is taunted by the “ghost” of her dead husband, but she refuses to “let him go.”

3rd ACTFalse Victory: Seeks Physical Immortality

The Kingdom is forced to a dire point. The young people about whom the Crone cares (particularly the Hero) are threatened, perhaps as a result of their own mistakes. She becomes very angry—both because of the suffering caused by Death and its threats, but also at the young people as well—their stupidity and their clear inability to be trusted with the Life of the Kingdom. She knows it is time to fully seek her power, but she does so by succumbing to the promise of physical immortality. She doesn’t complete the process, but her choice is enough to unleash the darkness.

In Up, Carl’s house (symbolizing his dead wife) is set on fire, and he has a meltdown in which he alienates and endangers his young Hero companion Russell.

Third Plot Point: Death Prevails

Empowered, the Sorcerer lets loose the Blight upon the Kingdom. The Angel of Death descends; Life begins not to be blotted out as the Crone feared—but to be overtaken by Death: zombified. The lines between Life and Death blur, and the horror is greater than if Death itself had prevailed. The Crone is aghast at her choice, recognizing that she was the one who skewed the balance of light and dark, Life and Death.

In Anne of Green Gables, Marilla realizes, on the eve of sending Anne back to the orphanage for stealing her brooch, that Anne was in fact innocent.

Climax: Embraces Death

The Crone is deeply humbled. She casts away the immortal power she has been offered. She accepts and embraces Death, not as an enemy but as the lover of Life. Life cannot exist without Death, just as the night cannot be without the day. She submits herself to the beautiful transformation of life. She does this with some hope of rectifying her mistakes, but largely she does it in total humility, simply awed and prostrate before the intolerable light of truth. She walks willingly through Death’s door to meet her fate.

In Fellowship of the Ring, Gandalf the Grey sacrifices himself to the Balrog (“You shall not pass!”) in order to salvage the rest of the Fellowship.

Climactic Moment: Death Transformed

Her wisdom transforms her from the mortal and feeble Crone into a powerful Mage. Death, now that it has been seen as beautiful through her eyes, is itself transformed. She has the power to thwart the Sorcerer and to restore the balance of Life and Death, lifting the Blight from the Kingdom even though she still cannot banish Death.

In Howl’s Moving Castle, Sophie (who has slowly regained her youth) rescues Howl from his monstrous fate.

Resolution: Reintegrates Into Renewed Kingdom

The Kingdom doesn’t fully understand what happened. They only know the Crone emerged from the Underworld, not only resurrected but transformed. They are in awe of her and more than a little frightened. They recognize in her a great new power, which they both trust and fear. They are happy that the Blight has lifted, even though they might be a little confused or even disgruntled that she did not end Death altogether. But she is wise and calm. She just smiles and does not tell them truths they are not ready to hear.

She is formally reintegrated into a respected role in the Kingdom, but even though she leaves her hut behind, it is not to return to the palace. Rather, she embarks on a mission that will take her all around the world as the Mage (which we will discuss next week).

At the end of Iron Lady, Margaret lets go of her hallucinations of her dead husband and surprises her daughter by “returning to the land of the living.”

Examples of the Crone ArcExamples of the Crone Arc include the following. Click on the links for structural analyses.

Sophie Hatter in Howl’s Moving Castle Elderly Margaret Thatcher in The Iron Lady Gandalf the Gray in The Fellowship of the Ring Hub McCann in Secondhand Lions Hec in The Hunt for the WilderpeopleLouis Waters and Addie Moore in Our Souls at NightHenry Dailey in The Black StallionMarilla and Matthew Cuthbert in Anne of Green GablesHepzibah in Lantern HillCarl Fredricksen in UpStay Tuned: Next week, we will study the Mage Arc.

Related Posts:

Story Theory and the Quest for MeaningAn Introduction to Archetypal StoriesArchetypal Character Arcs: A New SeriesThe Maiden ArcThe Hero ArcThe Queen ArcThe King ArcWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you think of any further examples of stories that feature the Crone Arc? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 6: The Crone Arc appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.