Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 4: The Queen Arc

What happens after the happily ever after? This is a question we often ask but seldom explore. As discussed in previous weeks, the two archetypal character arcs that begin the cycle of six “life arcs” are the Maiden and the Hero. Together, they account for a great majority of the archetypal stories we read and view, and together they act to resolve the protagonist’s initiation into adulthood—which often ends “happily” with the protagonist’s re-integration into a meaningful position of work and relationship within the larger tribe or Kingdom.

What happens after the happily ever after? This is a question we often ask but seldom explore. As discussed in previous weeks, the two archetypal character arcs that begin the cycle of six “life arcs” are the Maiden and the Hero. Together, they account for a great majority of the archetypal stories we read and view, and together they act to resolve the protagonist’s initiation into adulthood—which often ends “happily” with the protagonist’s re-integration into a meaningful position of work and relationship within the larger tribe or Kingdom.

But the vague “ever after” part of the phrase is only there if we choose not to follow the character into the life arcs of the Second Act of her life. Just as the two arcs of the First Act were characterized as representing the first thirty years of the character’s life, the next two arcs can be thought of as representing the Second Act and comprising the next thirty years—approximately from the ages of thirty to sixty.

Obviously what we see represented here is a more mature phase of life—an unequivocally adult phase. The protagonist has put behind her the challenges of individuation and initiation on her way to discovering healthy relationships, building her own family, and investing herself in meaningful work. But as any of us chronologically in the Second Act can attest, the adventure is far from over.

The Virgin’s Promise by Kim Hudson (affiliate link)

The challenges of the First Act were primarily about the character’s Relationship With Self and her ability to integrate the separate parts of herself. The Second Act arcs of Queen and King are about Relationship With Others. In The Virgin’s Promise, Kim Hudson mentions the many options for how this relationship may be dramatized:

The Mother/Goddess and the Lover/King know their power and must now enter into a relationship to use their power well and gain meaning in their life. This relationship can be between a man and a woman, a mother or a father and a child, and a woman or a man and her/his community. This union brings a form of wholeness.

If the overarching theme/challenge of the First Act was Fear, that of the Second Act is Power. The Queen, particularly, is an arc about learning to responsibly accept and use one’s power in relationship and in authority. The static archetype that lives between the Hero and the Queen is that of the Parent. After returning from the Hero’s adventures of the Quest, the initiated adult settles down and starts a family, whether literally or symbolically.

But the love the Hero learned in his arc is not enough to bear up the Queen’s growing burdens of responsibility. If she is to continue her maturation and grow her abilities to defend, enable, and direct the next generation of Maidens and Heroes in their own journeys, then she must grow beyond the role of loving Parent into the true leadership of the subsequent static archetype of Ruler—and its following arc of the King.

Dreamlander (Amazon affiliate link)

For me personally, the Queen Arc has been one of the most exciting to explore. As I’ve been outlining the sequel stories to my portal fantasy Dreamlander, I’ve been challenged to ask what we all ask sooner or later, “What happens to the Hero after the Hero’s Journey?” Is it just another Hero’s Journey? Instinctively, I think we all know that true characterization demands that the sequel for any Hero must offer an even deeper journey into the protagonist’s self.

As always, before we officially get started, I want to emphasize two important reminders that hold true for all of the arcs we’ll be studying.

1. The arcs are alternately characterized as feminine and masculine. Primarily, this indicates the ebb and flow between integration and individuation, among other qualities. Together, all six life arcs create a progression that can be found in any human life (provided we complete our early arcs in order to reach the later arcs with a proper foundation). In short, although I will use feminine pronouns for the feminine arcs and masculine pronouns for the masculine arcs, the protagonist of these stories can be of any gender.

2. Because these archetypes represent Positive-Change Arcs, they are therefore primarily about change. The archetype in which the protagonist begins the story will not be the archetype in which she ends the story. She will have arced into the subsequent archetype. The Queen Arc, therefore, is not about becoming the Queen archetype, but rather arcing out of it into the beginnings of the King Arc—and so on.

The Queen Arc: Defending the KingdomThe Queen represents who the Hero has become after returning from the Quest. She represents not just someone with the capacity for heroism, but also someone with a deep connection and compassion for those she previously saved—for her family and community.

That community—her Domestic World—is a rich and joyous place, full of love and nurturing, where she has found purpose and joy in guiding the Children and the directing the Maidens. But it is easy for her to lose herself at the Hearth, so to speak. It is easy to lose herself in this loving world and in the headiness of having so many adoring dependents—her children (literal or metaphorical) with whom she deeply identifies.

The Heroine’s Journey by Gail Carringer (affiliate link)

Fortunately, as in all stories, a catalyst arrives to prompt her growth into the next phase of her life (and her children into theirs). The Kingdom comes under threat from outside forces, and the current leadership proves itself incapable of protecting her family. In her book The Heroine’s Journey—which presents a model that aligns closely with the Queen Arc—paranormal romance author Gail Carringer states:

A key moment in any Heroine’s Journey is that precipitating fracture of family that will drive her into action.

Hmm. Whatever is a Queen to do?

Stakes: Accepting the Burden of LeadershipThe Hero had to realize that Love creates meaning, but the Queen must recognize that Love isn’t enough. There must also be Order, else all is Chaos—the children will all be spoiled brats who never leave their mother’s breast, never graduate from Maiden to Hero.

And yet there is a tremendous part of her that cannot bear that her children should grow up and leave her. Like all of the positive archetypes, she stands on the narrow center point between her negative poles—the Snow Queen and the Sorceress, who are often the villainous representations of corrupted power whom the Maidens (specifically) must overcome.

Sacred Contracts by Caroline Myss (affiliate link)

Instead, the Queen must now mature away from her own needs for connection. She must mature into the comparatively lonely role of the leader, willing to entrust responsibility to her able subordinates. Part of her challenge in becoming King is letting her children grow up. Because she enjoys being Queen, she doesn’t necessarily want to become King. Relinquishing her children feels like a Death (and indeed, symbolically, is). In Sacred Contracts, Caroline Myss discusses the inherent relationship focus of this archetype:

Challenges related to control, personal authority, and leadership play a primary role in forming the lessons of personal development that are inherent to this archetype. The benevolent Queen uses her authority to protect those in her court and sees her own empowerment enhanced by her relationships and experience.

Unlike the Maiden and Hero, who resist their incumbent evolution out of fear of the Powers That Be, the Queen resists change because she is content. She likes where she’s at and feels like she’s earned it. But necessity calls. Her brood grows too big. They need guidance. They need to be released from the Home into the Kingdom and beyond. She must transform and rise up to face the threats against the Kingdom by becoming the leader the Kingdom needs. Her love must grow from enveloping and protecting to enabling and ordering.

Her fear of becoming King isn’t because she lacks the qualities—power, will, intelligence. Her fear is that in giving up on her Queen identity, she can no longer be identified with her children—or they with her. No longer can she throw herself in front of a wayward child and tell the punisher—“Take me instead.” Now she must view her children as subjects and become, instead of their shield, an impartial arbiter.

Antagonist: The Empty ThroneThe catalyst that drives the Queen into action and growth is represented by an exterior threat to the Kingdom—symbolic Invaders. But the true antagonist within her story is the Kingdom’s lack of a mature and healthy leader to combat this threat. The Queen will start out appealing to what leadership exists—only to discover the throne is, symbolically, empty. It is occupied by either a Puppet or a Tyrant, and either presents as great a threat to the Kingdom from within as does the Invader from without.

Despite her initial attempts and desires to work within the existing system, the Queen must eventually realize that the only way to protect her children is to rise up and do it herself. She does this not out of a personal need (as does the Maiden) or a desire for glory (as does the Hero), but in defense of what she loves. Carringer states:

Theme: Power in RelationshipWhile our hero tends to move toward objects and acquisitions of power (a supernatural sword, magic amulet, and so on), the heroine’s descent is precipitated by a rejection of divine power (or defined social role) as a result of a familial connection (or relationship network) being taken from her. This can also be seen as a loss of identity or it can manifest in a more concrete way, such as an actual disguise.

The Maiden and Hero Arcs evolve the character into personal responsibility. The Queen and later the King Arcs now demand that the character evolve into relational and social responsibility. No matter what “invasion” may be threatening in the story’s outer conflict, this is the central thematic focus of the Queen’s arc. Hudson says:

The Mother/Goddess, the Lover/King … represent the middle stage of life, and all face the challenge of entering into a relationship with another.

Once again, it’s important to note that the language used throughout this series is, by nature, archetypal. We speak of Queens and Kingdoms and Invaders, but these concepts can be represented just as immediately in contemporary stories with none of these trappings.

One of my favorite examples of the Queen Arc is the baseball comedy A League of Their Own, which takes place against the backdrop of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League during World War II. In it, the protagonist Dottie (played by Geena Davis) reluctantly undertakes a Queen Arc, growing into mature leadership, cleverly outmaneuvering the threats from without that would shut down the league and the threats from poor leadership within (the alcoholic, apathetic “manager” played by Tom Hanks) to eventually demand individual responsibility from her “subjects”—the other players and particularly her Maiden-archetype younger sister.

Unlike the Hero who, in order to properly fulfill his growth challenges, must win alone, the Queen’s growth arc demands she enable others to work with her. She will start out in a more Heroic mindset, wanting to do it the way she did it before and spare everyone else the conflict, but she must learn that she cannot—that she is only able to save her family by enabling them to take up arms alongside her. Carringer again:

Key Points of the Queen ArcWhen in possession of political power, the heroine acts more like a military general (or a really good general manager), getting help, recognizing the strengths in others, and doling out tasks and requests for aid accordingly. Her objective is often to build and empower in the form of community, city, family, love.

For easy reference and comparison, I will be sharing some scannable summations of each arc’s key points:

Queen’s Story: A Battle.

Queen Arc: Protector to Leader (moves from Domestic World to Monarchic World)

Queen’s Symbolic Setting: Kingdom

Queen’s Lie vs. Truth: Control vs. Leadership

“Only my loving control can protect those I love.” versus “Only wise leadership and trust in those I love can protect them and allow us all to grow.”

Spiral Dynamics by Don Edward Beck and Christopher C. Cowan (affiliate link)

Queen’s Initial Motto: “We, the True Believers.”

(This is via Spiral Dynamics’ “Blue” Meme. If you’re not familiar with Spiral Dynamics, this probably won’t mean anything, but I was fascinated to realize that the six positive archetypal arcs line up perfectly with the “memes” of human development as found in the theory of Spiral Dynamics.)

Queen’s Archetypal Antagonist: Invader/Tyrant

Queen ’ s Relationship to Own Negative Shadow Archetypes:

Either Snow Queen finally acts in Love for her children by accepting Responsibility.

Or Sorceress learns to submit her selfish Love to the greater love of Responsibility.

Queen’s Relationship to Subsequent Shadow Archetypes as Represented by Other Characters: Empowers Puppet or overcomes Tyrant with her power.

The Beats of the Queen Character ArcFollowing are the structural beats of the Queen Arc.

1st ACT: Domestic WorldBeginning: Dangers of Dependency

The Queen is busy and fulfilled, caring for her growing children. But she is in danger of identifying herself too much with her children’s dependency upon her and therefore of binding her children to her too tightly instead of allowing them grow up and individuate via their own Maiden Arcs.

In the beginning of Places in the Heart before her husband is accidentally killed, Edna is content in her happy home as mother to her two children.

Inciting Event: Enemies at the Door

The Domestic World is threatened when enemies arrive from “without.” Unfortunately, there is no one fit to defend the Kingdom from these Invaders. It could be there is no King, or the King is incompetent and/or corrupt, or the current King is arcing into Crone (to be discussed next week) and recognizes he must name and train a successor.

Whatever the case, the King will prove unwilling or unable to defend the Kingdom from the Invaders, and the Queen’s realm will be threatened by this void of leadership. This “Call to Leadership” will be countered by a Refusal when the Queen resists immediately taking charge of her family’s defense and instead chooses to believe she can convince the existing King to do what is necessary.

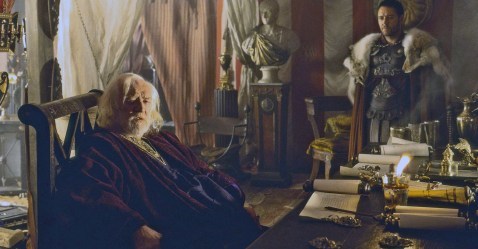

In Gladiator, when an aging Emperor Marcus Aurelius entreats Maximus to rule Rome after his passing, in order to protect it from his psychopathic son Commodus, Maximus refuses, desiring instead to return to his wife and son on his farm in Spain.

2ND ACT: Monarchic WorldFirst Plot Point: Entering the Castle

In order to entreat the King, the Queen reluctantly leaves her beloved Domestic World and enters the Monarchic World of the castle. She demands from him protection for her children. She may not immediately despair of the King’s ability to defend the Kingdom, but she accepts that she must do something herself—perhaps at the bidding the King, who is either trying to fob off his own responsibility onto her or simply fob her off.

In Elizabeth, the protagonist is crowned Queen of England, but she is not yet truly the ruler of her people. Her advisors rule the country and will not yet give her true power.

First Pinch Point: Children Clamor for Action

The Queen’s children aren’t content with her diplomatic attempts to assure their safety against the enemy. They believe in their mother more than they believe in the King, and they want her to take charge and help them defend the Hearth she has taught them to believe in and cherish. She resists this, neither wanting to leave her family for the throne, nor wanting her children to take up arms. She continues to hope and work for the King’s enablement against the Invaders.

In The Order of the Phoenix, Harry Potter secretly begins teaching other students, at their insistence, so they can form “Dumbledore’s Army” and resist Voldemort (“Invader”) and Professor Umbridge (“Tyrant”).

Midpoint: Leading the Charge

Finally, the Queen finds herself with no choice but to take charge herself and assume leadership/kingship in pushing back the Invaders. She comes to a Moment of Truth in realizing that her love alone is not enough to protect her children. More than that, she cannot rely on others (i.e., the King) to perform the necessary acts of restoring order to the Kingdom. But she cannot win alone; she must lead a charge made up of her subjects. She agrees to lead her children to battle.

The children wish to fight for their mother and make her King—but they also begin to fear that her growing power will trap them in childhood (as it will if she fails to arc into the King and instead slides into one of the negative archetypes of Snow Queen or Sorceress). If she does not let them fight with her, as they demand, then she will become an obstacle to their growth into adulthood. But if she signals her own increasing shift from Queen to King by not just allowing them to grow up but challenging them to do so and to fight behind her, she will signify that her Queen/Mother aspect will not hold them back. Indeed, her actions here not only signal her own shift from Queen to King but demands her children begin making their shift from Maiden to Hero.

In A League of Their Own, when the players learn their league is struggling, Dottie leads the charge with theatrical stunts that bring in crowds, inspiring the other players to do the same.

Second Pinch Point: Children Become Adults

The children, in part inspired by the Queen’s example so far and in part galvanized by her remaining hesitancy, individuate from her. They wish to take responsibility for their own lives, to become subjects rather than children (although they do not yet fully understand the weight of this choice). They insist she claim the throne, even though this may mean she must eventually start meting out impartial punishment to some of them, in spite of her love for them, to maintain order.

In Elizabeth, the queen demands her long-time love Lord Robert, in particular, “grow up” and take responsibility for his own foolishness and his role as her subject.

3rd ACTFalse Victory: Protects Her Children

The Queen makes a deal that protects her children—but it is at the expense of their independence. It represents a failure of leadership, in that she moves between negative archetypes—both the fearful and possessive “love” of the Sorceress and the total control of the Tyrant.

In It’s a Wonderful Life, George Bailey tries to bear the sole burden for the lost money. Instead of asking his friends for help, he tries to commit suicide to cash in his life insurance.

Third Plot Point: Kingdom in Chaos

The Queen’s attempt to protect her children without really assuming responsibility for leading them plunges the Kingdom into Chaos as the Invaders breach the borders.

In A League of Their Own, when Dottie’s husband returns, wounded, from the war, she decides to leave the team just before the World Series and go home. She does this in part for Kit, still “mothering” her.

Climax: Releases Her Children, Accepts Her Crown

The Queen accepts that she must trust her children to embark on their own journeys and to play their own parts in protecting the Kingdom under her guidance. She knowingly and willingly leaves behind the Domestic World forever and takes her place as a true leader of the Kingdom.

In 42, Jackie Robinson leads the Brooklyn Dodgers into the final game “as a team.”

Climactic Moment: Kingdom Is Saved

Working together, the Queen and her subjects are able to push back the Invaders and once again secure the borders of their Kingdom.

In The Post, newspaper publisher Kay takes control of her “kingdom” by publishing the revelation of a monumental government cover-up.

Resolution: Kingdom Prospers

The King is dead; long live the King. Having completed her arc, the Queen now ascends to the throne. No longer a Parent, she is now a Ruler. But her children are no longer Children; they have grown up as well. The cycle of life continues, and under her wise rulership the Kingdom prospers.

In Return of the King, Aragorn finally takes his throne as King of Gondor, restoring goodness to the realm as he begins his rule.

Examples of the Queen ArcExamples of the Queen Arc include the following. Click on the links for structural analyses.

Elizabeth I in Elizabeth Edna Spaulding in Places in the HeartGeorge Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life Joan in Joan of ArcHarry Potter in The Order of the Phoenix (among others in the series)Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings Jackie Robinson in 42Maximus in Gladiator Dottie Hinson in A League of Their Own Kay Graham in The PostBob and Helen Parr in The IncrediblesStay Tuned: Next week, we will study the King Arc.

Related Posts:

Story Theory and the Quest for MeaningAn Introduction to Archetypal StoriesArchetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 1: A New SeriesArchetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 2: The Maiden ArcArchetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 3: The Hero ArcWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you think of any further examples of stories that feature the Queen Arc? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 4: The Queen Arc appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.