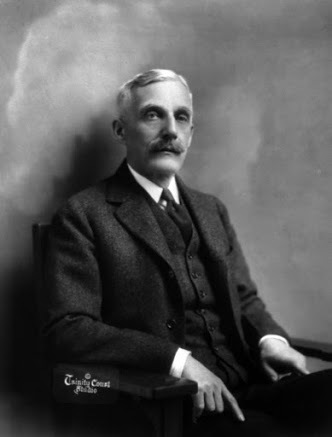

Andrew Mellon and the 1920-21 Depression

Andrew Mellon was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on March 24, 1855. Over the course of several decades, Mellon turned his father's modest bank into an extensive business empire that included national banks, insurance companies, trust companies, and investments in oil, steel, coal, and aluminum (including the company that would eventually become Alcoa). Perhaps Mellon's biggest influence in the 20th century came in the public sphere where he served as Secretary of the Treasury from 1921 until 1932, across the administrations of Presidents Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. Although most of the scholarly interest of Mellon's impact has focused on his overhaul of the income tax code during the 1920s and his close partnership with Calvin Coolidge, less attention has been given to his role in ending the 1920-21 Depression.

Scholarship across schools of economic thought have found differing causes to the Depression. Keynesians have take the position that the cause of the Depression was the result of high interest rates set by the newly-created Federal Reserve (whose creation is provided to us by Murray Rothbard) to fight inflation at the end of World War I. For example, Paul Krugman has argued that the Fed initiated "an inflation-fighting rececession...to bring the level of prices...down." Monetarists have arrived at a similar conclusion. In A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, Milton Freidman and Anna Schwartz added that the high interest rates came "not only too late but also probably too much." This led to "one of the most rapid declines on record." Too late in part because, according Allan H. Meltzer, the Fed struggled to become independent of political control by the Treasury Department. Dissenting from the Keynesians and monetarists are economists of the Austrian school, who argue the Depression came about because of artificially low interest rates after the war. According to the Austrians, this "easy money" policy was a credit-induced boom and the Depression was the bust, to use the terminology of Austrian Business Cycle Theory. The Fed's high interest rates were not the cause but rather the appropriate response to a Depression that had already begun.

On the political side, James Grant has argued that President Woodrow Wilson's stroke in 1919 together with the President's self-identified "single-track mind" focus on the League of Nations left all other policy concerns at a standstill. The result was, according to Grant, an economic policy that was "laissez-faire by accident."

The election of Harding in 1920--partly in response to Republican criticism that the Wilson administration had not done enough to combat the oncoming Depression--brought the longtime banker and businessman Mellon into the political fold. If Wilson was laissez-faire by accident, Harding and Mellon were laissez-faire by design. The war was a shock to an economy that had already been distorted by "unnecessary interference of Government with business" and "Government's experiment in business." Mellon's prescription, then, was to reverse this trend by reducing interest rates (the Secretary of the Treasury was then an influential ex-officio member of the Federal Reserve Board), reducing government expenditures (Mellon's program to reduce government expenditures continued the steep reductions at the end of the war such that federal spending in FY1919 of $18.5B was reduced to $3.3B by FY1922), and reducing income taxes.

While Mellon's program was generally focused on removing government interference in the economy, Mellon himself was not above engaging in what Gabriel Kolko termed "political capitalism." Despite his dedication to Harding's commitments, Mellon often advocated for interventionist economic policies (such as tariffs) which advanced the positions of his investments (many of which he retained control of while he was Secretary of the Treasury) and harmed his competitors.

Similar to the scholarly disagreements regarding the cause of the Depression, economists and historians diverge about how it ended. Keynesians like Krugman argued that the end came about as the result of the reduction in interest rates, and that "we have [nothing] to learn from the macroeconomics of Warren Harding." Among Austrian economists, Patrick Newman found that Mellon's steep cuts in government expenditures accelerated the end of the Depression and advanced the recovery, but that Mellon's efforts to lower interest rates was part of a long-term effort that kept rates below the market. Grant concluded that "the depression of 1920-21 was the beau ideal of a deflationary slump." Summing up the Austrian position, Robert P. Murphy declared that "[t]he free market works."

The economic influence of Andrew Mellon on the American economy as a whole during his long tenure as Secretary of the Treasury is undeniable. Mellon's economic impact during the Depression of 1920-21 is less clear. Mellon's influence on the Federal Reserve Board clearly expedited the reduction of interest rates in 1921. This easing marked the end of the Depression, but raised concerns among Austrians that the oncoming boom would be unsustainable. The austerity in federal spending that began after the War and accelerated Mellon was unlike anything we have seen since. Whether this deliberate policy, together with reductions in income tax rates, was unremarkable or helped to free up resources for the market to reallocate is a matter of interpretation. In any case, Andrew Mellon put an indelible stamp on a period in history we are unlikely to ever experience again.

Bibliography

Friedman, Milton, and Anna Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971.

Grant, James. The Forgotten Depression. 1921: The Crash That Cured Itself. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014.

Krugman, Paul. "1921 and All That." New York Times, April 1, 2011.

Kolko. Gabriel. Triumph of Conservatism. New York: Free Press, 1977.

Kuehn, Daniel. "A Critique of Powell, Woods, and Murphy on the 1920-1921 Depression." Review of Austrian Economics 24, no. 3 (09, 2011): 273-91.

Meltzer, Allan H. A History of the Federal Reserve, Volume 1 : 1913-1951. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Meltzer, Allan H. "Lessons from the Early History of the Federal Reserve." Presidential Address to the International Atlantic Economic Society, March 17, 2000.

Murphy, Robert P. "The Depression You've Never Heard Of: 1920-1921." Foundation for Economic Education. https://fee.org/articles/the-depressi....

Newman, Patrick. "The Depression of 1920-21: A Credit Induced Boom and a Market Based Recovery?" Review of Austrian Economics 29 (2016): 387-414.

Rothbard, Murray N. America's Great Depression. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2000.

_______. “The Origins of the Federal Reserve.” The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 2, No. 3 (Fall 1999): 3-51.