Michael Schearer's Blog

July 7, 2024

My finalized dissertation

Our Enemy, the State: Liberty versus Power on the American Home Front during the First World War (SSRN, Liberty Commons):

World War I marked a significant shift in the structure and practice of the federal government. The key feature of this shift was the centralization of national power in the federal government and a burgeoning bureaucracy. This increase in the centralization of power led to an escalation of conflicts between the expanded assertions of national power and the civil liberties of American citizens. While this relationship between state power and civil liberties has been the focus of extensive scholarly research, much less has been written about a mostly forgotten perspective that viewed war as destructive to human flourishing beyond the dictates of court-defined civil liberties. Based upon a classical liberal tradition, shaped by the experiences of those who lived through the war and adapted by a subsequent generation of libertarian scholars, this study examines the transformation of social power into state power during the First World War through this perspective. American participation in the war redistributed power from the voluntary interactions within society to the coercive hand of the state. The war apparatus on the home front played upon existing prejudices and invented new ones by co-opting social institutions into state-endorsed mechanisms of coercion. Ultimately, the war unleashed a major acceleration in the transformation of social power into state power. This transformation represented a fundamental shift from a society that placed great emphasis on voluntarism to one centered on the use of the force of the state to achieve political aims. In this post-war statism, war became the health of the state, and its long-lasting effects are felt even today.

March 29, 2022

Liberty vs. Power and the Legacy of the First World War

Across all of American history, the accumulation of state power during times of war and national emergency has been the most destructive threat to human liberty. World War I was no exception. Thousands of books have been written about the first World War. Despite this, much less has been written about a mostly-forgotten anti-war perspective put forth by those in the classical liberal or libertarian tradition. This includes many who are now considered the “Old Right,” including Albert Jay Nock, who examined the relationship of social power (liberty) and state power. This methodology was adapted and described by Murray Rothbard as “the great conflict which is eternally waged between Liberty and Power…."[1] According to Rothbard: “In those areas of history when liberty—social power—has managed to race ahead of state power and control, the country and even mankind have flourished. In those eras when state power has managed to catch up or surpass social power, mankind suffers and declines.”[2] The central concern of the American story is: “Who will control the state, and what power will the state exercise over the citizenry?”[3] More recently, historians such as Robert Higgs have demonstrated how governments used crises to increase their power.[4]

The focus of this dissertation will be the major political, legal, and economic events of the First World War in the United States within the context of this Rothbardian methodology. While some classical liberal and libertarian scholars such as Rothbard, Higgs, and Ralph Raico have written essays or chapters about the first World War, none of them did so in a full-length treatise from this classical liberal conflict methodology. Moreover, libertarian scholars have tended to focus on economic history. Among more recent works among more orthodox scholars, books such as William G. Ross's World War I and the American Constitution addresses many important legal issues.[5] Nonetheless, it is tied to court cases that are important to, but not sufficient, to express to full measure of social power eclipsed by the war. My thesis envisions that social power (or human liberty) can be diminished even if there is court decision on the matter, and even when there might be no legal cause of action to justify a complaint.

As a result, there is a gap in the scholarly work in this area. My dissertation seeks to fill that gap by examining the first World War in the context of its impact on American society through the lens of the classical liberal conflict theory. My focus will be on specific instances or situations (political, social, economic, and legal) where social power was converted into state power. A few examples that stand out are the takeover of the railroads, activities of the American Protective League and the Council of National Defense (and its state and local associates), and how these organizations contributed to surveillance and prosecution for draft evasion, espionage, and other crimes—and how the courts were complicit in this conversion. Moreover, many victims of these activities suffered because of state-enforced nativism and discrimination. Here again, much has been written about these activities in a substantive manner. The intent is not to duplicate work that has already been done but to show how these activities were part of an overall scheme to centralize government at the expense of liberty.

What is the classical liberal conflict theory? This question is designed to answer and understand the methodology that my research will be based upon. Class conflict theory is widely attributed to Karl Marx and is a staple of Marxist historical analysis. But research (mostly in the 20thcentury) has demonstrated that this class conflict analysis was seen as early as the 16th century and predated his work, a fact that he acknowledged. The existence of this history is due to the research of libertarian scholars Ralph Raico, Leonard Liggio, David M. Hart, Walter E. Grinder, and others. These historians showed the development of this classical liberal or libertarian class analysis as distinct from Marx. Rather than capitalist vs. working class based upon the payment of wages, these historians showed that the classical liberal analysis was (and is) based upon wielding the power of government to achieve one’s means. Rothbard synthesized the ideas of classical liberals and the Old Right, Austrian economic theory, and contributions from the New Left.

How did the war transform the relationship between the American people and their government as seen through the lens of the Rothardian synthesis? This dissertation is not about the causes of the war, information about battles or strategy or tactics, nor does it focus on diplomacy or the peace settlement after the war. All of these subjects are important to the overall framework, but they are not intended to be covered in any comprehensive way. Instead, the central argument is the relationship between the American people and their government that emerged during and immediately after the war—as seen through the lens of Rothbard's conflict theory. The approach of this dissertation is, first: to explain the convergence of historical factors that served as justifications or rationalizations for the centralization power; second, to describe the methods by which implementation took place; and third, demonstrate how this power was consolidated.

What is the legacy of World War I, as seen through this perspective? For many Americans, the First World War is a forgotten war. While millions of Europeans died in over for years of trench warfare, the United States was at war for only 19 months and involved in only a few months of direct combat operations in the summer and fall of 1918. Yet the legacy of the war--especially it unfolded on the home front. The war had immediate effects in areas such as free speech, immigration, and even rent control. Later, much of the administrative structure of the New Deal was directly inspired by the American war effort. Perhaps the legacy of the war impacts us even today.

[1] Murray N. Rothbard, Conceived in Liberty, vol. 1 (Auburn, AL: Mises Institute, 2011), xv-xvi.

[2] Ibid., xvi.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Robert Higgs, Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government (Oakland: Independent Institute, 2013).

[5] William G. Ross, World War I and the American Constitution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

April 18, 2021

"Fred Perkins." March of Time, vol. 1, ep. 1 (New York: HBO, 1935).

Narrator: Fred Perkins, 56, one time Cornell fullback, now a small manufacturer of wet cell batteries, calls his 10 employees to the workshop, back of his brick home at York.

Fred Perkins: Frank, meeting out back, come on.

Employee: Okay.

Fred Perkins: Boys, some of the big battery companies have complained about me to NRA. According to the code, I should pay you $0.40 an hour. I've raised your pay from $0.20 to $0.25, it's the best I can do.

Employee: We know it, Fred.

Employee: We are satisfied.

Fred Perkins: They say, I'm liable for a fine of $500 a day if you go on working for $0.25.

Employee: We know what you are up against.

Employee: Yeah, forget it.

Employee: That don't apply in small towns.

Employee: That's right.

Fred Perkins: What do we do? Will you work for $0.25?

Employee: We're with you, Fred.

Fred Perkins: We'll go ahead and see what happens.

Employee: So do we.

A few months later --

in Fred Perkins:' home

Victoria Perkins: Is that you Fred?

Fred Perkins: Yes, hello, darling. Someone from Harrisburg came in this afternoon.

Victoria Perkins: Harrisburg, who was it?

Fred Perkins: A fellow named Wilson, a Federal Marshal.

Victoria Perkins: What did he want?

Fred Perkins: It's about that code business of men's wages.

Victoria Perkins: Are they still hounding you about that?

Fred Perkins: Yep.

Victoria Perkins: Oh, that's too bad.

Fred Perkins: This time, they cracked down. He had a warrant for my arrest.

Victoria Perkins: Fred?

Fred Perkins: He told me I'd have to post $5,000 or go to jail.

Victoria Perkins: $5,000!

Fred Perkins: I know, I haven't got 5,000, don't know where to get it.

Victoria Perkins: What did you tell him, Fred?

Fred Perkins: What could I tell him. I told him I'll go to jail and I meant it, I'm going to fight this thing through to a finish.

Narrator: To jail goes Fred Perkins, but he does not take his feet lying down. He continues to run his business and his story becomes national news. A rich fellow townsman goes his bond, and after 18 days in jail, between a burglar and a counterfeiter, Fred Perkins is released to await trial. He is convicted, fined, and now to higher courts moves the Perkins' case as eminent lawyers volunteer their services. Harold Beitler of Philadelphia is joined by David Aiken Reed, lately the field horse of Republican opposition in the Senate. To the defense come famed Democrats, John W. Davis of New York, James A. Reed of Missouri, Newton D. Baker of Ohio. Fred Perkins:' legal champions resolve that his case shall go to the Supreme Court of the United States. And nine august jurists, who compose the Supreme Court, will try not Fred Perkins, but the NRA, for they are the trustees of the US constitution. Their Chief, at the dedication of their new temple of justice, emphatically declared:

Charles Evans Hughes: The fundamental conceptions of limited governmental powers and an individual liberty have persisted despite crises of disruption and expansion and still remains triumphant and unyielding.

February 18, 2021

Economic Theories of the Great Depression

To understand the Great Depression is the Holy Grail of macroeconomics....[F]inding an explanation for the worldwide economic collapse of the 1930s remains a fascinating intellectual challenge. We do not yet have our hands on the Grail by any means....To that extent, historians and economists have provided a range of explanations both for what caused the Great Depression and for how it ended. Some of these explanations overlap and some are contradictory or mutually exclusive. In either case, we would be wise to heed the words of the political theorist James Burnham, who wrote that "[c]hanges in society do not result from the exclusive impact of any single cause, but rather from the interdependent and reciprocal influences of a variety of cases...." We should consider single cause explanations, but only when they fit within a larger "pluralistic theory of history."

The monetarist explanation, as provided by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, argue that the Federal Reserve allowed a reduction in the money supply which caused deflation and its associated effects, including falling incomes and prices and more unemployment. This theory was endorsed and expanded upon by Bernanke, who in a 2002 speech said:

Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression, you're right. We did it. We're very sorry. But thanks to you, we won't do it again.A modern monetarist explanation for the end of Great Depression is provided by Christina Romer, who advances the argument that an inflow of gold to the United States during the mid and late 1930s served to stimulate aggregate demand.

Keynesian economics, on the other hand, finds the cause of the Great Depression in an unrestrained capitalist boom during the 1920s which eventually crashed; a reduction of investment then caused a decrease in aggregate demand. A negative difference between aggregate demand and potential output denotes a recessionary gap. The Keynesian prescription for a recessionary gap is to boost aggregate demand primarily through government-directed stimulus spending. This narrative also relies on a belief that then-President Herbert Hoover failed to act in any meaningful way following the stock market crash of 1929, which prolonged and worsened the Great Depression. The most prominent modern exponent of Keynes is Nobel laureate and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, who has argued that World War II was "the great natural experiment in the effects of large increases in government spending" to stimulate a depressed economy. War spending as the reason for the end of the Great Depression is consistent with the standard Keynesian model.

A third explanation, which can be seen as an extension of the classical economic theory of Adam Smith and David Ricardo, is the Austrian school. According to the Austrians (among them, Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard), the boom of the 1920s was caused not by unrestrained capitalism but by the Federal Reserve through artificially low interest rates. Instead of reducing interest rates, as the Fed did after the crash, it should have allowed rates to rise (the Fed's aggressive rate cuts between 1929 and 1931 cut strongly against the monetarist explanation). This would have allowed employment to shift to different areas of the economy. The Fed's intervention in the economy is the chief cause of "boom" and "bust" business cycles, of which the Great Depression is the prime example. Moreover, Benjamin Anderson and Rothbard exploded the now-tired myth that President Hoover failed to act. The key distinction between monetarists and Keynesians, on one hand, and Austrians, on the other hand, is the role of the government in ending the Great Depression. Monetarist and Keynesian explanations support government intervention, while Austrians contend that intervention made the Great Depression much longer than it would have been. Mises would scoff at Krugman's notion that war could end a depression; he wrote that "[w]ar prosperity is like the prosperity that an earthquake or plague brings." Austrians argue, then, that wealth cannot result from destruction.

Scholarship by Robert Higgs, Steven Horowitz, and Michael McPhillips have shown that the "consensus" view that wartime spending ended the Great Depression is incorrect. Instead, as Higgs and Larry Schweikert explain, savings and bond holdings accumulated during the war were spent as the ending of the war became more certain. Optimism and confidence rebounded. Despite a 61 percent decrease in federal government spending from 1945 to 1947, a 20.6% decline in GNP in 1946, and an influx of ten million servicemen into the civilian economy, the private sector rebounded and flourished, in part because the "regime uncertainty" of the 1930s (as explained by Higgs) had subsided. As Horowitz and McPhillips write, "[t]hose who credit the war with economic recovery by virtue of giant government expenditures and rising GNP must also explain the absence of any genuine economic downturn following the war."

The monetarist and Keynesian explanations for both the cause of the Great Depression and for its end are compelling narratives. But heterodox views such as those of the Austrian school have continued to deflate the validity of these narratives, first, by challenging the underlying evidence; and second, by proposing an alternate theory that is more consistent with the available data. Although the debate over the economic theories of the Great Depression will not be resolved by a single blog post, my review of the relevant literature finds the Austrian narrative to be a more persuasive explanation.

Bibliography

Anderson, Benjamin M. Economics and the Public Welfare: Financial and Economic History of the United States, 1914-1946. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand Company, 1949.

Bernanke, Ben S. "The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression: A Comparative Approach." Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 27, no. 1 (1995): 1-28.

Burnham, James. The Machiavellians: Defenders of Freedom. New York: The John Day Company, 1943.

Friedman, Milton, and Anna J. Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971.

Higgs, Robert. Depression, War, and Cold War: Studies in Political Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Horwitz, Steven and Michael J. McPhillips. "The Reality of the Wartime Economy: More Historical Evidence on Whether World War II Ended the Great Depression." The Independent Review 17, no. 3 (2013): 325-347.

"Interest Rates, 1914-1965." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. October 1965.

Keynes, John Maynard. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Krugman, Paul. "Oh! What A Lovely War!" New York Times, August 15, 2011.

Mises, Ludwig von. Between the Two World Wars: Monetary Disorder, Interventionism, Socialism, and the Great Depression. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2002.

______. Nation, State, and Economy. New York: New York University Press, 1983.

Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke, At the Conference to Honor Milton Friedman, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, November 8, 2002. https://www.federalreserve.gov/boardd....

Romer, Christina D. "What Ended the Great Depression?" The Journal of Economic History 52, no. 4 (1992): 757-84.

Rothbard, Murray N. America's Great Depression. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2000.

Schweikert, Larry. "The Economic Impact of War on Business." Liberty University.

February 11, 2021

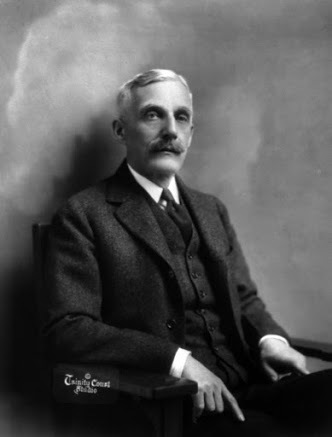

Andrew Mellon and the 1920-21 Depression

Andrew Mellon was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on March 24, 1855. Over the course of several decades, Mellon turned his father's modest bank into an extensive business empire that included national banks, insurance companies, trust companies, and investments in oil, steel, coal, and aluminum (including the company that would eventually become Alcoa). Perhaps Mellon's biggest influence in the 20th century came in the public sphere where he served as Secretary of the Treasury from 1921 until 1932, across the administrations of Presidents Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. Although most of the scholarly interest of Mellon's impact has focused on his overhaul of the income tax code during the 1920s and his close partnership with Calvin Coolidge, less attention has been given to his role in ending the 1920-21 Depression.

Scholarship across schools of economic thought have found differing causes to the Depression. Keynesians have take the position that the cause of the Depression was the result of high interest rates set by the newly-created Federal Reserve (whose creation is provided to us by Murray Rothbard) to fight inflation at the end of World War I. For example, Paul Krugman has argued that the Fed initiated "an inflation-fighting rececession...to bring the level of prices...down." Monetarists have arrived at a similar conclusion. In A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, Milton Freidman and Anna Schwartz added that the high interest rates came "not only too late but also probably too much." This led to "one of the most rapid declines on record." Too late in part because, according Allan H. Meltzer, the Fed struggled to become independent of political control by the Treasury Department. Dissenting from the Keynesians and monetarists are economists of the Austrian school, who argue the Depression came about because of artificially low interest rates after the war. According to the Austrians, this "easy money" policy was a credit-induced boom and the Depression was the bust, to use the terminology of Austrian Business Cycle Theory. The Fed's high interest rates were not the cause but rather the appropriate response to a Depression that had already begun.

On the political side, James Grant has argued that President Woodrow Wilson's stroke in 1919 together with the President's self-identified "single-track mind" focus on the League of Nations left all other policy concerns at a standstill. The result was, according to Grant, an economic policy that was "laissez-faire by accident."

The election of Harding in 1920--partly in response to Republican criticism that the Wilson administration had not done enough to combat the oncoming Depression--brought the longtime banker and businessman Mellon into the political fold. If Wilson was laissez-faire by accident, Harding and Mellon were laissez-faire by design. The war was a shock to an economy that had already been distorted by "unnecessary interference of Government with business" and "Government's experiment in business." Mellon's prescription, then, was to reverse this trend by reducing interest rates (the Secretary of the Treasury was then an influential ex-officio member of the Federal Reserve Board), reducing government expenditures (Mellon's program to reduce government expenditures continued the steep reductions at the end of the war such that federal spending in FY1919 of $18.5B was reduced to $3.3B by FY1922), and reducing income taxes.

While Mellon's program was generally focused on removing government interference in the economy, Mellon himself was not above engaging in what Gabriel Kolko termed "political capitalism." Despite his dedication to Harding's commitments, Mellon often advocated for interventionist economic policies (such as tariffs) which advanced the positions of his investments (many of which he retained control of while he was Secretary of the Treasury) and harmed his competitors.

Similar to the scholarly disagreements regarding the cause of the Depression, economists and historians diverge about how it ended. Keynesians like Krugman argued that the end came about as the result of the reduction in interest rates, and that "we have [nothing] to learn from the macroeconomics of Warren Harding." Among Austrian economists, Patrick Newman found that Mellon's steep cuts in government expenditures accelerated the end of the Depression and advanced the recovery, but that Mellon's efforts to lower interest rates was part of a long-term effort that kept rates below the market. Grant concluded that "the depression of 1920-21 was the beau ideal of a deflationary slump." Summing up the Austrian position, Robert P. Murphy declared that "[t]he free market works."

The economic influence of Andrew Mellon on the American economy as a whole during his long tenure as Secretary of the Treasury is undeniable. Mellon's economic impact during the Depression of 1920-21 is less clear. Mellon's influence on the Federal Reserve Board clearly expedited the reduction of interest rates in 1921. This easing marked the end of the Depression, but raised concerns among Austrians that the oncoming boom would be unsustainable. The austerity in federal spending that began after the War and accelerated Mellon was unlike anything we have seen since. Whether this deliberate policy, together with reductions in income tax rates, was unremarkable or helped to free up resources for the market to reallocate is a matter of interpretation. In any case, Andrew Mellon put an indelible stamp on a period in history we are unlikely to ever experience again.

Bibliography

Friedman, Milton, and Anna Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971.

Grant, James. The Forgotten Depression. 1921: The Crash That Cured Itself. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014.

Krugman, Paul. "1921 and All That." New York Times, April 1, 2011.

Kolko. Gabriel. Triumph of Conservatism. New York: Free Press, 1977.

Kuehn, Daniel. "A Critique of Powell, Woods, and Murphy on the 1920-1921 Depression." Review of Austrian Economics 24, no. 3 (09, 2011): 273-91.

Meltzer, Allan H. A History of the Federal Reserve, Volume 1 : 1913-1951. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Meltzer, Allan H. "Lessons from the Early History of the Federal Reserve." Presidential Address to the International Atlantic Economic Society, March 17, 2000.

Murphy, Robert P. "The Depression You've Never Heard Of: 1920-1921." Foundation for Economic Education. https://fee.org/articles/the-depressi....

Newman, Patrick. "The Depression of 1920-21: A Credit Induced Boom and a Market Based Recovery?" Review of Austrian Economics 29 (2016): 387-414.

Rothbard, Murray N. America's Great Depression. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2000.

_______. “The Origins of the Federal Reserve.” The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 2, No. 3 (Fall 1999): 3-51.

January 29, 2021

Differences in Regional Per Capita Income Between the Northeast and South, 1860-1900

The primary dataset for this discussion blog is "Interregional Differences in Per Capita Income, Population, and Total Income, 1840-1950," by Richard A. Easterlin, in Trends in the American Economy in the Nineteenth Century. A summary of the relevant data for this blog is reproduced in The American South: A History:

In 1860, just before the outbreak of the Civil War, personal income in the Northeast was nearly double that of the South (139% vs. 72%). By 1900, personal income in the Northeast remained steady (137%) while the South stumbled to 51% by 1880 and remained there through 1900. It would take until 1950, 85 years after the conclusion of the Civil War, for personal income in the South to regain the same level from 1860.

What factors explain differences in regional per capita income between the Northeast and South from 1860 to 1900?

The first and most obvious answer is that such differences in income can be explained by destruction during the war. Virtually all of the war was fought in the South. According to historian Philip Leigh, Southern railroad capacity was cut by two-thirds. The war destroyed two-thirds of all livestock. Bank capital was reduced by three-quarters. By one estimate, the direct cost of the Civil War to the South was $3.3B (1860 dollars).

This destruction was enormous, but it did not have to be permanent. For example, historian James F. Doster showed that some extensively damaged southern railroads still managed to show operating profits in 1865 and that the "cost of physical reconstruction was relatively modest." Northern businessmen headed south to help finance rebuilding of railroads during Reconstruction, which grew by 46% between 1865 and 1875; while track mileage increased from 11,000 miles in 1870 to 29,000 miles in 1890. Cotton production across the South surpassed 1860 levels (5.4M bales) by 1880 (5.7M bales).

Although books such as Eric Foner's Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 and Philip Leigh's Southern Reconstruction reach radically different conclusions about the intentions and motivations for Reconstruction, it is possible to find at least some common ground in understanding factors to explain the differences in regional per capita income.

Property Confiscation. More than 2M bales of cotton (worth an estimated $17M in 1865 prices) were confiscated after the war. While such confiscations were consistent with a series of confiscation acts passed during the war, the disposition of the cotton was not. Consistent with existing Supreme Court precedent, confiscated property should have been held in trust with the owner given an opportunity to demonstrate their loyalty (Mrs. Alexander's Cotton, 69 U.S. 404 (1865).

Pensions. From 1866-1890, fully 12% of all federal expenditures ($1.145B) went toward generous pensions for Union war veterans (so generous that the last Civil War pension payment was paid to the daughter of a Union veteran in May 2020 when she died!). By 1893, pensions for Union veterans amounted to over 40% of the budget. Federal expenditures (including pensions) were funded primarily by tariffs and taxes paid by both regions, although Confederate veterans received no pensions from the federal government.

Tariffs. Whether one subscribes to the Beale-Beard hypothesis that Northern businessmen supported high tariffs for political control and economic gain, or the more recent view that the North was split on tariffs, the end result was that high tariffs hurt the ability of the South to export cotton.

Freight Rates. Due in part to the costs of repairing and replacing damaged rail lines as well as problems of scale, interstate freight rates were significantly higher in the South. The National Emergency Council's Report on Economic Conditions of the South (1938) found that such rates were 39% higher for southern manufacturers as compared to those in the Northeast despite the fact that the primary reasons for the higher rates had long disappeared. According to the report, "this difference in freight rates creates a man-made wall to replace the naural barrier long since overcome by modern railroad engineering." It would take until the 1940s for the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to modify these discriminatory rates.

Banking Regulations. The National Banking Acts of 1863, 1864, and 1865-66 created a system of national banks that the South was not able to take advantage of because of higher capital requirements (the combination of tariffs, property taxes to fund Reconstruction governments, and higher freight rates left southerners perpetually strapped for cash), geography (the one branch limitation was not suited to the rural southern population), and high taxes on state banks.

Foner concludes that Reconstruction was a moral crusade for black equality. The departure of troops from the South in 1877 represented an unfinished revolution that deprived free blacks of that equality and subjected them to decades of Jim Crow. Leigh finds that the Reconstruction policies of the Radicals were primarily motivated by a desire for political power, and as such punitive in nature. The result was decades of poverty among both whites and blacks in the South. The differences between Foner and Leigh are largely about intent (the moral crusade vs. political power) and focus (equality of blacks vs. poverty among both whites and blacks). The factors cited above, many of which help to explain differences in regional per capita income between the Northeast and the South from 1860 to 1890 do not rely on intent or motivation or focus. Instead, these factors are based upon the results of Reconstruction, regardless of the intent of the Radical Republicans. Within this small window, Foner and Leigh share a small bit of common ground. Whether through deliberate intent to punish or as the undesireable result of the end of Reconstruction, these policies had the impact of impoverishing blacks and whites in the South decades beyond where it might have regained its earlier stature.

Bibliography

Cooper, Jr., William J. and Tom E. Terrill. The American South: A History. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990.

Doster, James F. "Were the Southern Railroads Destroyed by the Civil War?" Civil War History 7, no. 3 (September 1961): 310-320.

Easterlin, Richard A. "Interregional Differences in Per Capita Income, Population, and Total Income, 1840-1950." In Trends in the American Economy in the Nineteenth Century (National Bureau of Economic Research), 73-140. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1960.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

Goldin, Claudia D. and Frank D. Lewis. "The Economic Cost of the American Civil War: Estimates and Implications." Journal of Economic History 35 (2): 299-326.

Harris, Seymour E., ed. American Economic History. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961.

Leigh, Philip. Southern Reconstruction. Chicago: Westholme Publishing, 2017.

Murray, Robert B. "Mrs. Alexander's Cotton." Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 6, no. 4 (1965): 393-400.

Report on Economic Conditions of the South. Washington, DC: National Emergency Council, 1938.

Stover, John F. "Georgia Railroads During the Reconstruction Years." Railroad History, no. 134 (1976): 55-65.

September 11, 2020

Daher TBM 930 Ferry Flight

June 24, 2020

Checkmate

April 22, 2020

Podcast subscriptions, April 2020

Backstage Journal with Rhett Shull

The Bob Murphy Show

Bound by Oath

The Brion McClanahan Show

Cato Daily Podcast

Contra Krugman

Daily Audio Bible

Grammar Girl

Lexicon Valley

The Libertarian Podcast

Make No Law

Part-Time Genius

RadioLab Presents: More Perfect

Serial

Short Circuit

This American Life

The Tom Woods Show

The Way I Heard It with Mike Rowe

The Week in Review at Abbeville Institute

February 26, 2020

Collaborative Research: Hampden-Sydney College

As Chapter Three opens, the Presbyterian minister William Graham had traveled with his student Archibald and others east across the Blue Ridge Mountains to Briery, a small town on the border of Charlotte and Prince Edward counties. It is 1789 and at the time of what Alexander called "the Great Revival" (almost certainly the beginning of what we now call the Second Great Awakening). "[I]n the very midst of revival scenes, Graham and his students met Dr. John B. Smith, son of the Rev. Dr. Robert Smith and brother of Rev. Samuel Stanhope Smith.

Alexander provides additional detail in Chapter Eight. Samuel Stanhope Smith proposed a college in south-central Virginia in 1771 and raised funding as well as identified faculty (which included his brother, John). After the Presbytery of Hanover secured a gift of 100 acres two miles north of Nathaniel Venable's Slate Hill plantation (about an hour east of Lynchburg, Virginia), the Presbytery founded the school in 1775 and named Smith its first president. At the suggestion of Dr. John Witherspoon, the Scottish-Presbyterian minister and President of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, Smith named the school Hampden-Sydney College after the English republicans John Hampden and Algernon Sidney (Alexander uses the older spelling Sidney which the college also used, but later changed to the alternate spelling Sydney). The first board of trustees included James Madison and Patrick Henry, among others. The college has been in continuous operation ever since.

John B. Smith became the captain of a company of students around 1777 and assigned to the defense of Williamburg, although there is no evidence if they were ever involved in operations during the Revolutionary War.

Samuel Stanhope Smith stayed on as the first president until 1779 when Samuel was called to the College of New Jersey and his brother John became president until 1789. Archibald Alexander would travel to Hampden-Sydney again where he met the vice president (and acting President) Drury Lacy, who served in that capacity in 1797 when Alexander himself became president (until 1806). Union Theological Seminary (now Union Presbyterian Seminary) was founded at Hampden-Sydney in 1812 where it stayed until moving to Richmond in 1895.

Archibald Alexander would go on to become the first professor and founding president at the Princeton Theological Seminary in 1812 where he would serve until his death in 1851.

The history of Hampden-Sydney College is maintained in part by the Esther Thomas Atkinson Museum. Many of the buildings on campus are named for notable people in the college's history, among them Cushing, Graham, and Venable.

Among the valuable primary sources available for the college is a book of the Calendar of Board Minutes from 1776 to 1876. This book also includes a narrative history of the college and portraits of many of the early trustees.

Here is an advertisement for the college that was published in the (Williamsburg) Virginia Gazette on September 1, 1775 (transcription below the image):

"By the generous exertions of several Gentlemen in this and some of the neighbouring Counties, very large contributions have lately been made for erecting and supporting a public Academy near the Courthouse in this County. Their zeal for the interests of Learning and Virtue has met with such success, that they were enabled to let the Buildings in March left to several Undertakers, who are proceeding in their Work with the greatest Expedition. A very valuable library of the best Writers, both ancient and modern on most Parts of Science and polite Literature, is already procured; with Part of an Apparatus to facilitate the Studies of the Mathematicks and Natural Philosophy, which we expect in a short Time to render complete.

The Academy will certainly be opened on the 10th of next November. It is to be distinguished by the name Hampden-Sidney, and will be subject to the Visitation of 12 Gentlemen of Character and Influence in their respective Counties; the immediate and active Members being chiefly of the Church of England. The Number of Visitors and Trustees will probably be increased as soon as the Distractions of the Times shall so far cease as to enable its Patrons to enlarge its Foundations.

The Students will all board and study under the same Roof, provided for by a common Steward, except such as choose to take their Boarding in the Country. The rates, at the utmost, will not exceed 10£. Currency per Annum to the steward and 4£ Tuition Money; 20 shillings of this to be always paid at Entrance.

The system of Education will resemble that which is adopted in the College of New Jersey; save, that a more particular Attention shall be paid to the Cultivation of the English Language than is usually done in Places of public Education. Three Masters and Professors are ready to enter in November, and as many more may be easily procured as the increased Number of Students may at any Time hereafter require. And our Prospects at present are so extremely flattering that it is probable we shall be obliged to procure two Professors more before the Expiration of the Year.

The Public may rest assured that the whole shall be conducted on the most catholic Plan. Parents, of every Denomination, may be at full Liberty to require their Children to attend on any Mode of Worship which either Custom or Conscience has rendered most agreeable to them. For our Fidelity, in every Respect, we are cheerfully willing to pledge our Reputation to the Public; which may be more relied on, because our whole Success depends upon their favourable Opinion. Our Character and Interest, therefore, being at Stake, furnish a strong Security for our avoiding all Party Instigations; and our Care to form good men, and good Citizens, on the common and universal Principles of Morality, distinguished from the narrow Tenets which form the Complexion of a Sect; and for our assiduity in the whole Circle of Education."

~Samuel S. Smith

P.S. The principal Building of the Academy not being yet completed, those Gentlemen who desire their Children to enter immediately will be obliged to take Lodgings for them in the Neighbourhood, during the Winter Season; which may be done in Houses sufficiently convenient, on very reasonable Terms.References

Alexander, James W. The Life of Archibald Alexander, D.D., L.L. D., First Professor in the Theological Seminary, at Princeton, New Jersey. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1857.

Esther Thomas Atkinson Museum

Hampden-Sydney College History

History of Hampden-Sydney College

Morrison, Alfred J. Calendar of Board Minutes, 1776-1876. Richmond, VA: The Hermitage Press, 1912.