A Thanksgiving Ghost (1900)

Not the most exceptional story, but a number of newspapers at the time thought readers across the country would enjoy it well enough over a period of a few years, a sampling of which papers are identified here. "A Thanksgiving Ghost" has at least a couple tropes in common with some of the Christmas ghost stories of the time.

The author Rodrigues Ottolengui (1861-1937) has a wide-ranging and genuinely interesting biography at The Golden Age of Detection Wiki. A Charleston, SC native from a Sephardic family, he moved to New York where he practiced dentistry and helped pioneer forensic dentistry. He wrote several stories and novels of detective fiction, a number of which sound quite intriguing.

The story here could be called an example of occult detective fiction...maybe. As a mystery, it's pretty thin. There's some rather obvious things to have done early on that somehow didn't occur to the family or the investigating doctor in the story. That said, people who were attending seances at the time often simply sat as directed, perhaps with hands linked, without trying to get up to examine anything they were hearing or seeing. The same could be said of the audiences for television psychics - how many get out of their seats to see if there's an earpiece in a person's ear, for example?

CP

The author Rodrigues Ottolengui (1861-1937) has a wide-ranging and genuinely interesting biography at The Golden Age of Detection Wiki. A Charleston, SC native from a Sephardic family, he moved to New York where he practiced dentistry and helped pioneer forensic dentistry. He wrote several stories and novels of detective fiction, a number of which sound quite intriguing.

The story here could be called an example of occult detective fiction...maybe. As a mystery, it's pretty thin. There's some rather obvious things to have done early on that somehow didn't occur to the family or the investigating doctor in the story. That said, people who were attending seances at the time often simply sat as directed, perhaps with hands linked, without trying to get up to examine anything they were hearing or seeing. The same could be said of the audiences for television psychics - how many get out of their seats to see if there's an earpiece in a person's ear, for example?

CP

A Thanksgiving Ghost

By Rodrigues Ottolengui

I HAD not intended to call upon Dr. Rawson when I left my home, my destination, if indeed I had any, being one of my clubs; but it began to rain suddenly, and, being without an umbrella, I welcomed the light in the doctor’s study as I chanced to pass his house. When I was ushered into his cozy little den, I was rather surprised to find the doctor sitting in a large Turkish chair and gazing into a bright log fire which blazed most invitingly in the big chimney place. I say I was surprised because this was the first time I had ever found him alone, without a great leather covered tome of some kind in his hand. For a man who possessed as much knowledge as did Dr. Rawson it had always seemed to me that he had the most voracious appetite for learning. Indeed, his attitude so struck me that I could not help commenting upon it.

“My dear doctor,” said I, “why so pensive? You look as though your best patient had just died—your best paying patient, I mean, for, of course, doctors are not expected to mourn over every death.”

“Your guess is a good one,” replied the doctor quietly. “A very good patient of mine died an hour ago—a very good patient and a very good friend.”

“Indeed, I am very sorry to hear it,” said I, putting off my bantering tone. “Was there anything special about his case? Did he die unexpectedly, or anything of that sort? The reason I ask is because you seem to be in one of your studious moods. One might almost imagine that you are pondering over his case. Your diagnosis was correct, of course?

“I am pondering over his case, and I am not sure about my diagnosis.”

“You don’t mean that you have made any mistake?”

“Perhaps, but not as you mean it. My friend was troubled with angina pectoris and had suffered a long time. I knew that he could not live long, and so did he. He had no fear of death, and consequently I was perfectly frank with him from the outset. His death tonight was even sooner than we had anticipated, but, of course, in such cases the exact duration of life cannot be prognosticated.”

“How, then, was there a mistake in your diagnosis?” I was puzzled.

“I did not say that there was. I do not know, and that is the trouble.”

“Explain, please.?

“My friend was a spiritualist. On all other subjects he was certainly as rational as any man. Indeed, he was educated far beyond the average of even college bred men. Still he believed in spirits—believed that the dead return to this world, I mean.”

“There are lots of such people in the world,” said I. “They resemble a cogwheel with one cog broken, I take it. In rapid revolution the weak spot is not noticed. It is only when the attention is drawn specifically to the spot that the imperfection is seen. But what about your mistake in diagnosis?” I was thus persistent because I had come to believe the doctor infallible as a diagnostician.

“Oh, that was but a figure of speech,” he replied, smiling. “I alluded to my general opinion of the man. I thought as you do—that he was a mild sort of monomaniac simply because he held to his spiritualistic views.”

“Cause enough,” said I. “Surely no sane man could believe that spirits walk the earth.”

“That has been my view also. Still just before his death tonight he broached this subject. He declared that he would yet convince me, and that he would do it by returning to visit me after death.”

“Ah, so that is it! You were looking into the fire just now and waiting for your friend’s ghost to appear. Well, well! You astonish me.” I laughed aloud. “Come, come, doctor. I am glad I dropped in to cheer you up. I tell you what; ghosts they say, do not get out much before 12, and it is not yet 9. If you’ll mix me a punch, I’ll stay with you till the witching hour and stand by you in your encounter with the specter.”

“He did not say that he would come tonight,” said the doctor, with a smile, taking my chaffing good naturedly.

“Well, I imagine not. He was smart enough not to fix the hour, not knowing what engagements might be waiting for him after he had ‘passed over,’ eh? I think that’s the lingo, is it not? But, I say, did this friend of yours believe in ghosts theoretically or practically? Did he just prove the things to himself by the Scriptures or philosophy or something of that sort, or had he ever seen a real live ghost? A real live ghost is rather good, eh?

“He claimed to have seen a great many materialized spirits.”

“The deuce he did! Why, then, look here. How is it, if he was so intimate with ghosts—on visiting terms, as it were—how was it that he never introduced you to one of his celestial visitors?”

“He did once.”

“What’s that?” I hardly thought I could have heard aright. I knew Dr. Rawson to be a hard headed, logical scientist; not the sort of man at all to take up with such beliefs as returning ghosts, specters that nightly perambulate on the stroke of midnight, much as the cuckoo shows himself at the door of the clock.

“Would you like me to tell you of my experience?” asked the doctor. Of course I accepted, but before he began the story he went to his cupboard and brought forward the ingredients with which to brew a punch of his own concoction of which he knew that I was very fond.

“The incident occurred only last November,” began the doctor. “Just before Thanksgiving day I received a letter from my friend insisting that I should go out to his house in the country. It is a place not 50 miles from New York, but I shall not tell you exactly where because—well, for reasons. He had only been there himself for a few weeks, but was enchanted with his new home, which was in a sort of park—one of those private parks containing a number of residences. He was very urgent about my going and explained that if I would only give him the time from Thanksgiving to the next Monday morning he would undertake to dispel my doubts as to materialization. In short, he promised to show me a spirit returned to earth. And he added rather mysteriously, ‘The character of this manifestation is such that even you will not charge fraud.’ I had been working pretty hard, and the temptation was great to have a few days in the country. Strange to say, the hope of seeing my friend’s ghost repelled rather than attracted me. I was satisfied that there was trickery of some kind and felt reasonably certain that I should discover the truth. I was equally sure that my friend was honest, and I was loath to be a party to his discomfiture when I should have shown up his ghost in its true colors.

“I reached the station about noon on Thanksgiving day, an important surgical case having compelled me to stay in town over the previous night. My friend met me and took great delight in showing me over his new home. The family, of course, were cordial, as I had long been on closely intimate terms with them—in fact, I called his wife and two girls by their names. The wife, Margaret, was one of those hero worshippers, he husband being the hero. She saw everything as he saw it, and, of course, was as firmly fixed in spiritualistic theories as he. The eldest daughter, Stephanie, was college bred, a Vassar graduate, and not only believed in spiritualism, but could prove it, or thought she could, mathematically, logically, psychologically and philosophically. She was the pride of her father and his mainstay in an argument. The other girl, Fanny, was my favorite, and if she believed in ghosts I am sure it was only because of her environment. She had no fixed ideas of her own. Then there was the youngest child, Charlie, the satan of the family, a boy of 13. This young rascal openly avowed a firm belief in ghosts within earshot of his parents, but, while vouching for the accuracy of his father’s many tales of visiting specters, not infrequently Charlie would slyly wink one eye at me. Here I may as well say frankly that I associated my friend’s latest ghost with Charlie. I expected that, should I discover the secret strings which moved the specter, I would likewise find that Charlie was pulling them. In this connection, I was destined to meet my first mystification.

“To my surprise, my friend said nothing about the ghostly visitation from the moment of my arrival up to the time when I was shown to my room to make my toilet for dinner. I attributed this to his innate courtesy and natural diffidence. He evidently hesitated to bore me too soon with his theories, or, as I had often called it, his fad. While I was washing there was a light rap on my door, and Charlie walked in.

“‘Say, doctor,’ said he, getting at his topic without delay, ‘I suppose dad’s told you about our spook, and you’ve come up to see her, haven’t you?’

“‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘But I did not know it was a female. Have you seen her yourself?’ I thought I might as well pump the youngster at once.

“‘Have I seen her?’ said he. ‘Well, I guess yes. Say, doctor, I can trust you, can’t I?’

“‘Why, certainly,’ said I. It seemed that my discoveries were to be all too easy. But I was mistaken.

“‘Well,’ continued Charlie, ‘you must know then that I never took any stock in dad’s ghosts—that is, not in any of the others. Of course, I’ve seen a lot of them, and then again, there’s been a lot more that dad said he saw but I didn’t see, though I’ve agreed with him, because—well, just to make him happy. A boy must do that, eh, doctor?’

“‘You sly young rascal!’ thought I, but I merely answered with a nod, and he went on.

“‘You see, all the other ghosts and ghostesses were just common, everyday sort of spooks. Things with sheets round them, and they most generally came in the dark, when there was little chance to tell much about their looks. They might have been the mediums, you know, at least some of them. But it’s different with this ghost we’ve got now. She’s a beauty, and there don’t seem any chance for a humbug about it.’

“‘Why not?’ I asked, wondering whether the humbuggery were not going on at the very moment.

“‘Well, in the first place, it’s such a little bit of a ghost. She must have died when she was not more than 7 or 8 years old, I should think. Anyway, she’s only so high,’ indicating with his hand held above the floor. ‘You would hardly expect a medium to make up for a little one like that, now, would you? It’s easier to believe in the ghost notion.’

“The boy puzzled me. Either he was speaking honestly and in spite of his avowed skepticism had seen something which had convinced him or else he was a most artful little trickster. His argument about the medium was not to be denied, and if he had properly indicated the height of the little visitant he was himself much too tall to enact the part. This he could not have done in any event, for I had determined to keep him in sight when the expected time for the ghost should have arrived.

“‘A grown person could hardly make up for so small a ghost, I must admit,’ said I. ‘But how do you know it is not a child who does this trick?’

“‘What child, doctor? I know all the youngsters that live around here, and, anyhow, why should a kid 8 years old wait up till 12 or 1 o’clock every night just to take a walk through our hall and make believe she’s a ghost? A kid might do that once, but not every night for more than a month. No, I guess we’ve got a real spook this time. You wait till you see her. I didn’t believe in it myself, you know, but this spook knocks me. Well, I’ve got to dress, too, so goodby.’

“This conversation rather upset my ideas. I had counted on Charlie as the real spirit inventor, or at least as an ally in finding out the truth, and now at the outset he declared that had himself come to believe in the genuineness of the materialization. I descended to the dining room in a most thoughtful mood, but once there my time was too fully occupied with greetings of friends and neighbors who had come in to fine to long harbor ideas about ghosts. The dinner was a remarkably fine one. It was evident that neither my host nor his wife permitted spiritualism to interfere with the proper nourishment of the physical man. Each course was daintily served and, if anything, proved more enjoyable than the preceding. The subject of ghosts or materialization came up but once during the dinner, and then in a most incidental way. One of the guests, an elderly man, speaking to Margaret, said:

“‘Did you know when you took this house that it is supposed to be haunted? I hope you have never been troubled by the ghost?’

“‘No; we have had no trouble whatever with any ghost,’ said Margaret. And then she added, ‘May I have another ice brought for you?’

“This indicated to me at once that my friends, because of their sensitiveness to criticism, had carefully concealed their spiritualistic beliefs. Consequently it would appear to be a most singular coincidence that any of their new neighbors should have inaugurated a practical joke and should have so persistently kept it up as to have the spurious specter appear for so many nights consecutively. I began to find myself wishing for the moment when I might see the visitation with my own eyes and judge for myself. It was after 11 o’clock when all the guests had departed and I found myself alone with my friends, and now the subject which seemed to have been so long tabooed was at once broached.

“‘The hour approaches, doctor,’ said my friend, ‘when we may expect our visitor. Do not imagine that I mean midnight. I hope you credit me with more intelligence than to suppose I countenance the fanciful notion that the dead leave their shrouds at the stroke of 12 and return to their graves at cock crow.’

“‘I hope so,’ said I, with a smile.

“‘Nevertheless, it is true that our little friend has never come before 12. That, of course, is a mere coincidence. Sometimes it may be within half an hour after the great town clock chimes the hour, and, again, she has been as late as 1 or even 2 o’clock.’

“‘Do you mean that she comes every night and that you wait up to see her?’

“‘We do now. At first we did not realize that her visits were to be so regular, and several times we retired without seeing her. One night, however, I happened to get up again, and, coming through the hall, I met the dear one just departing. Since then we have always awaited her coming, and have never been disappointed.’

“‘You mean that you form a circle and sit in the usual way?’

“‘Not at all. This is not a seance. That is the wonderful part of it. There is no medium connected with this. The spirit, though a young one, must have great power to be thus able to manifest unaided.’

“‘Am I to understand that this manifestation, as you call it, has been seen by all of you?’

“‘By all of us, and, moreover, she comes right into this room, where all the lights are burning, a thing heretofore supposed to be impossible. Thus, you see, we have all had ample opportunity to see her.’

“‘Have you ever spoken to this visitor?’

“‘Many times, but thus far we have been unable to obtain any reply. Ah! There go the midnight chimes.’

“We listened to the beautiful bells, which sounded loudly in the stillness of the night, till the last peal had died away. Then it was Stephanie who spoke:

“‘Doctor,’ said she, ‘you are a skeptic, are you not?’

“‘No,’ said I, with a smile. ‘Let me rather claim to be an agnostic.’

“‘Very good. After tonight you will be a believer. But you have no heard Fanny sing lately. Her voice has greatly improved. Fanny, will you sing something?’

“The girls moved over to the piano. I noted that Charlie was near the door leading into the hall and that he was intently gazing out into the dimly lighted passage. Was he brewing mischief? I went over to him and, taking him by the arm, said:

“‘Never mind the spook, Charlie. She’ll come when she is ready. Come over and hear your sister sing.’ He looked up at me most quizzically, and them, after a moment, he laughed softly and beckoned me to lower my head, that he might whisper, whereupon he said, so low that the others could not hear:

“‘I’m on. You think I’m working the ghost; but you’re off. Wait till you see her. I tell you, she’s the real thing. I’ll stick to you close to show I’m honest in this.’

“And he did. From that moment he was never more than three feet away from me, so that any connection that he might have had with the apparition evidently did not require his personal attention. Fanny sang two or three melodies most charmingly, and then suddenly I felt a tug at my coat, and turned to see Charlie pointing toward the door, through which what appeared to be a little girl entered. The others had not yet noticed the apparition, and it came so suddenly and so silently that for an instant I was stunned. I use the word advisedly. My mind seemed to refuse either to comprehend what I saw or to argue against it. All that I had ever said against spiritualism was dissipated from my mind as one wipes chalk marks from a blackboard. Slowly my mind seemed to grasp the idea that here was a veritable returned spirit, and such a dainty, beautiful little apparition! A childish face, as devoid of deceit as one might imagine an angel’s. A lovely face, too, peeping out from a wealth of golden locks, which in the lamplight shone as a halo. It was impossible to gaze upon this apparition and harbor the least suspicion of fraud. She came into the room slowly, stepping carefully, until she stood in the center. Then she turned and glided toward the bay window. By this time we were all watching. At the window she stooped to her knees, put her two hands together, and her little lips moved as in prayer. So she knelt a few minutes, and then, rising slowly, she retraced her steps and, passing out into the hall, disappeared.

“As soon as she had gone I looked silently at my friends, hardly knowing what to say. Stephanie broke the silence.

“‘Well, doctor,’ said she, ‘what do you think?’

“‘I think I would like to go to bed at once,’ said I, not daring to discuss the subject without having time to think it over. No objection was made, nor was there any comment upon my apparent anxiety to shirk all talk of what I had seen. Such was the extreme courtesy of these people.”

* * * * * * *

“Well, that was certainly a wonderful experience, doctor,” said I, interrupting the narrative. “But, of course, it was some kind of a trick?”

“You would not have thought so had you been present. There were several exceedingly strange features of this matter which occurred to me during the sleepless hours which I passed. I say sleepless, for my conviction of the fact that there are no ghosts had been sadly shattered by what I had seen, and I struggled to regain my mental equilibrium. In a sense I still believed there could be no such thing as ghosts, but there was a disturbing doubt engendered by that dainty little being, ghost or whatever she might have been. The angelic face, the prayerful attitude, made it impossible to think she was alive and playing a trick. Never once did she take note of the persons present. It did not seem possible that one so young could play such a part night after night and never show consciousness of the presence of those whom she was trying to deceive. Unlike traditional ghosts, on the other hand, she was fully dressed in a dainty white muslin, tricked out with tiny pink ribbon bows—a most unghostly costume.

“Tired out at last, I must have slept, for I awoke suddenly in the morning an hour past my usual time for arising and was dazed at my strange surroundings, the sun streaming in through the window making me aware of the lateness of the hour. I hastily jumped in and began my toilet, when in a moment the occurrence of the previous night came into my mind. At first I was inclined to dismiss it as a dream, but a little thought convinced me that my recollections were too vivid for anything short of reality. In the breakfast room I found the family assembled and was painfully aware of the fact that I was expected to either explain the mystery of the apparition or else to admit myself converted to their views. Still for some time the subject was not brought up, Charlie at last being unable to keep still any longer.

“‘Doctor,’ said he, ‘what do you think of the little ghost lady? Would you believe it, dad, he thought I was playing tricks on you? Where do you think I could get such a pretty little spirit, doctor?’

“‘The whole affair seems quite mysterious to me,’ said I, ‘I am afraid I ate too much Thanksgiving dinner to be a competent witness.’

“‘Oh, you mean,’ said Stephanie, ‘that this was only a Thanksgiving ghost, or, rather, a ghost resulting from too much Thanksgiving dinner?’

“The girl’s tone irritated me, already annoyed as I was because I had no explanation of what I had seen ready to offer. So I said testily:

“‘I certainly would like to see the apparition again when I had eaten less, although, of course, Margaret,’ I added, turning to my hostess, ‘the dinner was beyond all doubt the best I have ever eaten. But too full a stomach makes the mind slow.’

“‘Then you doubt the genuineness of the manifestation?’ my friend asked.

“‘I certainly do not doubt you, my friend,’ I hastily replied, ‘but I cannot under the circumstances so quickly give up my own views. In spite of the warning that she was to come, the little lady rather took me by surprise, and I was hardly in the condition to consider what I saw from a scientific standpoint.’

“‘Ah! But science,’ said Stephanie, ‘can but support the theory of spiritualism. There are three great entities in the universe, each imperishable in itself—matter, force and spirit. Science must recognize this trinity and that all forms are but the union of the three in varying proportions. The highest form—man—is the highest simply because of the preponderance of the spirit which is in the combination. This preponderance is so great that whereas the destruction of any other form, such as a mineral, resolves the components into separate particles, which, by attraction, rush back into the parent source and are lost, in man the spiritual portion is great enough to resist this attraction after death and to continue as a separate entity. By appropriating to itself a portion of the superabundant matter and force which is everywhere in ether, it is possible for this spirit to appear to mortals as a re-embodied being.’

“This glib Vassar college girl’s explanation of spiritualism made me lose my temper, and I replied, with little courtesy:

“‘And when these spirits re-embody I suppose it is quite natural that they should find clothes and dress themselves before appearing to us poor mortals. The little girl last night had on a party dress, with ribbon bows on it. Why did she bother about all that? Why do not spirits come without clothing?’

“‘I do not know,’ replied Stephanie, without losing her self control for a moment. ‘I do not pretend to know everything. The spirits think it well to conform to earthly customs, I suppose, or, perhaps, it is merely the result of past habits while in the flesh.’

“I have always found that it is useless to argue with spiritualists. They always have ready answers, which are plausible, however illogical. My friend saw that I was in an ill humor and hastened to smooth the troubled atmosphere.

“‘Doctor,’ said he, ‘you said just now that you were not in a condition last night to investigate the manifestation in a scientific manner. Nothing would please us all better than to have you test this matter scientifically if you can. I am sure that if you should confirm our reports of what we have seen your words would convert many to the great truth.’

“Like an inspiration, an idea crossed my mind, and without hesitation I answered:

“‘I will agree to try a scientific experiment tonight if you will permit it without interference.’

“‘I would not like to make so rash a promise without knowing what you purpose.’

“‘Let me explain, then. I have been as much interested in hypnotism as you have been in spiritualism. You know enough of that to recognize the fact that hypnotism is an influence over the mind rather than over the body. Any effects upon the body are operations through the mind. To make my meaning plainer, you would consider it folly were I to undertake to hypnotize a dead body?’

“‘I should think you insane.’

“‘And rightly. But’— I hesitated to make my proposition, thinking that it would be unwelcome. ‘But would it be insanity to endeavor to hypnotize a disembodied spirit?’ The result was quite astonishing to me.

“‘I see what you mean to do!’ cried Stephanie enthusiastically. ‘It is a grand experiment. You will try to hypnotize the spirit which appears here. Agree to the doctor’s proposal, father. It will be a great scientific achievement.’

“‘Why, certainly, I agree,” said my friend, with equal enthusiasm. ‘I can imagine great results. If the disembodied spirit could be hypnotized, it might be compelled to reveal what up to now all materialized spirits have declined to tell.’

“That day was a long one for us all, for every one impatiently awaited the hour for the experiment, and I may at once come to that. This time I was not so much astonished as on the night before, yet I must confess that for a moment I was tempted to abandon my experiment. For one instant I felt that it would be sacrilegious to interfere with what, after all, might be supernatural. What if it were a spirit? I could not positively know to the contrary. Suppose my hypnotic experiment should succeed, and that some great secret of the universe should by this means be revealed? Was I prepared to endure the consequences, to suffer the displeasure of my Maker? Thus, with all our vaunted faith in scientific knowledge, our firmest beliefs may be shaken in a moment, for after all belief is not knowledge, our firmest beliefs may be shaken in a moment, for after all belief is not knowledge. I believed that this apparition was not a ghost, but I did not know it. Watching the movements of the little visitor, which were most lifelike, and, spurred by the recollection that those present were eagerly expecting me to act, I plucked up courage to proceed. I waited till the pantomimic prayer was over and the little girl was walking toward the door. Then I intercepted her path and stood perfectly still until she came quite close to me. She did not appear to notice me until she had come close enough so that her outstretched little hand touched me. Then she stopped and stood still. I gently took her hand, whispering, ‘Be not afraid.’

“As I touched her she started and trembled violently. But as I spoke she as quickly became quiet. I recognized at once that my experiment was to succeed, and so proceeded with regained confidence.

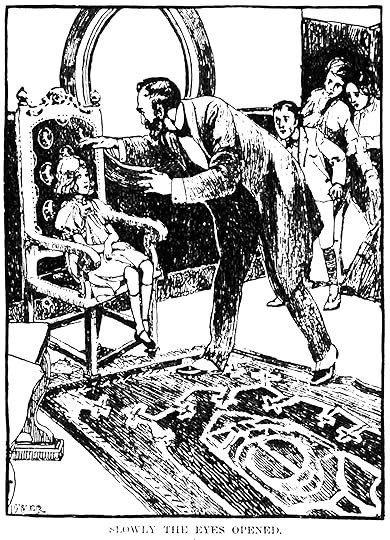

“‘Sleep!’ said I. ‘Sleep deeply! More deeply still!’ I touched her eyes lightly with the tips of my fingers, and they closed. ‘Do as I bid you,’ I continued. ‘Come; follow me.’ I walked across the room, and the girl followed. Stephanie uttered a cry of astonishment mingled with pleasure, but at a sign from me she became silent again. The girl sat down in a chair, and I stood in front of her.

“‘You are asleep,’ I said. ‘You are asleep, but you are awake. You see me. Open your eyes and look at me closely.’ Slowly the eyes opened, and the little one gazed at me. ‘So. Look at me well. Will you know me again? Speak! Answer! You can speak.’

“I fancied I could hear the heart beats of those in the room as they waited breathlessly for their ghost to speak. At first the girl merely looked long and earnestly into my face, but presently the lips trembled, and I saw that there was an effort to speak.

“‘Speak! Answer!’ I said again, more commandingly. ‘You see me! Will you always know me again?’

“‘Yes.’

“She spoke. It was but one word, but to my auditors a hypnotized materialized spirit had been compelled to speak. You may imagine their interest in what I should say or do next.

“‘You know how you came here?’ said I.

“‘Yes.’

“‘You can come again?’

“‘Yes.’

“‘You will come again if I wish?’

“‘Yes.’

“‘Then listen. Listen and remember. Remember and do. Come again. Come tomorrow. When the clock chimes 12, come again. But come at the chiming of the bell in the daytime—not in the night. You are not afraid of the light?’

“‘No.’

“‘Then you will come?’ This time there was no answer. I touched the eyelids again, and they drooped and closed. ‘So. Sleep,’ said I. ‘Sleep deeply. Now you are asleep. Listen! Listen and obey! Come tomorrow when the clock chimes 12 in the daytime. Come at that hour, and in the daytime. Come! Now, answer. Will you come?’

“‘Yes.’

“‘That will do. Now return whence you came.’ Immediately and swiftly she turned and glided away out of our sight. I was at once surrounded by my friends, congratulated on my success, and at the same time criticised because I had not asked more important questions. In answer to this I declared that we should treat this spirit as we would any hypnotic subject. At the first experiment too much should not be expected. Monosyllables were all that we had been able to obtain by way of speech, but we had charged this spirit to appear to us in broad daylight. A hypnotized living person would obey such an injunction. It would be a great achievement to compel a ghost to do so. To this they agreed and went off to bed satisfied that the experiment promised to be a great success.

“At the noon hour on the next day we were all assembled, impatient for the denouement. The town clock had scarcely chimed before our little maiden appeared. She came into the room with apparent nervousness and glanced timidly about. Finally her eyes rested on me, and instantly she ran lightly to me, jumped up into my lap and cried:

“‘I know you. You told me to come, and so I came.’

“Just then another person entered the room—a young woman in the garb of a trained nurse.

“‘I am so glad I have found you, Rosie,’ said she, taking the child off my knee. ‘What made you run away?’

“The mystery was solved. We were dealing not with a ghost, but with a child who was an invalid because of a nervous disease from which she suffered. Charlie had never seen her because she was closely confined to the house or taken out of the doors in the carriage, and always in the care of her nurse. But she was a little somnambulist. During the previous year she and her parents had lived in the house now occupied by my friends, and it had been her nightly habit to come into the room where we had seen her and to kneel at her mother’s side to say her prayers. One night there had been a party, and while dressed in the pretty little frock in which she had visited us she had suffered from her first seizure. To indicate to you how deep an impression upon the mind may be, I have no doubt that it was because on that night, being taken away from the room while ill, she had not as usual said her prayers, that during her somnambulistic walks she dressed herself in her party frock again and came over to say her prayers. This is especially plausible, because about the same time the mother had been taken ill, and for some months had been in a sanitarium, so that after that party night the little one had never knelt at her mother’s side.”

“But why did she come only at night” I asked.

“In the first place, it was only at night that she could evade the vigilance of her nurse, and, what is equally important, it would be only at night that the idea of saying her prayers would recur to her mind. You note that when she came in the daytime, in obedience to hypnotic suggestion, her nurse was close behind her.”

“What did your friends say when they found that their ghost was alive?”

“Just what all spiritualists say when a ‘manifestation’ is exposed. That the explanation covers only that one instance, and that they have had other experiences that leave their faith unshaken.”

“Well, doctor,” said I, “my experience with spirits leaves my faith unshaken in those of your mixing. Here’s your good health, and my the spirit of your departed friend come not back to trouble you. Pleasant dreams, and good night.”

Helena Independent [MT]. November 25, 1900: 9.

Topeka Weekly Capital [KS]. November 30, 1900: 6.

Highland Democrat [Peekskill, NY]. November 21, 1903: 12.

Asheville Citizen-Times [NC]. November 22, 1903: 17.

Fort Worth Telegram [TX]. November 22, 1903: 20.

Asheville Weekly Citizen [NC]. November 24, 1903: 5.

Capital Journal [Salem, OR]. November 25, 1903: 10.

Amsterdam Evening Recorder [NY]. November 25, 1903: 12.

Mansfield Advertiser [PA]. November 25, 1903: 1.

Gloucester Country Democrat [NJ]. November 26, 1903: 8.

Benton Advocate [WI]. November 26, 1903: 10.

Daily Herald [Delphos, OH]. November 26, 1903: 7.

Published on November 26, 2020 14:14

•

Tags:

thanksgiving-ghost-stories

No comments have been added yet.

Christmas Ghost Stories and Horror

I was fortunate enough to edit Valancourt Books' 4th & 5th volumes of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories. Things found while compiling are shared here. (Including some Thanksgiving Ghost items.)

I was fortunate enough to edit Valancourt Books' 4th & 5th volumes of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories. Things found while compiling are shared here. (Including some Thanksgiving Ghost items.)

...more

- Christopher Philippo's profile

- 8 followers