A further reply to Glenn Ellmers

At Law and Liberty, Glenn Ellmers has repliedto my response to his review of my book

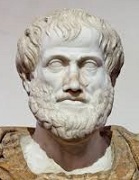

Aristotle’s Revenge

. He makes two points, neither of them good.

At Law and Liberty, Glenn Ellmers has repliedto my response to his review of my book

Aristotle’s Revenge

. He makes two points, neither of them good.First, Ellmers reiterates his complaint that I am insufficiently attentive to the actual words of Aristotle himself. He writes: “This where Feser and I part. He thinks that it is adequate to have some familiarity with ‘the broad Aristotelian tradition’ – a term of seemingly vast elasticity. I do not.” Put aside the false assumption that my own “familiarity” is only with the broad Aristotelian tradition rather than with Aristotle himself. It is certainly true that my book focuses on the former rather than the latter. So, is this adequate? Well, adequate for what purpose? If I had been writing a book about Aristotle himself, then I would agree with Ellmers that citing the broad Aristotelian tradition is not sufficient and that I should have emphasized Aristotle’s own texts. But as I said in my initial response to him, and as any reader of the book knows, that is not what the book is about.

As Aquinas says in his commentary on Aristotle’s On the Heavens, ultimately the study of philosophy is not about knowing what people thought, but rather about knowing what is true. The latter has always been the primary concern of my own work. Obviously I have a very high regard for thinkers like Aristotle and Aquinas, but I have always been less interested in doing Aristotle and Aquinas exegesis than in expounding and defending what I think they happened to have gotten right.

Hence, what I am concerned with in Aristotle’s Revenge are certain ideas, such as the theory of actuality and potentiality, hylemorphism, and the notion of teleology. These ideas are historically associated most closely with Aristotle, but lots of later thinkers also had important things to say about them. But the book is not about those thinkers either. It is not a book about the history of ideas any more than it is a book about the person Aristotle. Again, it is a book about the ideas themselves. In particular, it is a book about whether the ideas are sound, and if so, how they relate to what modern science tells us about the nature of space and time, the nature of matter, the nature of life, and so on.

Now, in a book that is about the ideas themselvesrather than about specific thinkers or about the history of ideas, it would be tedious and irrelevant to cite a litany of names and works and explain exactly who said what, where and when. Indeed, it would be counterproductive, because it would only reinforce the widespread false impression that the ideas can only be of interest to students of the history of thought, and have no contemporary relevance. Noting that they represent “the Aristotelian tradition” thus suffices for the specific purposes of my book.

Really, what’s the big deal? It isn’t a hard point to grasp. Once again, Ellmers shows that he is the sort of book reviewer who insists on evaluating a book as if it were about a topic that he is personally interested in and competent to speak about. And what he is personally interested in and (I guess) competent to speak about is Aristotle exegesis. Hence he keeps trying to bring the discussion around to that, like the guest you get stuck sitting next to at a dinner party who won’t shut up about some pet topic he is obsessed with.

Ellmers’ other point concerns teleology. In response to my objection that he has failed to understand the specific notion of teleology that is at issue when discussing basic inorganic causal relations, he says:

Again, who’s view are we talking about? How is one to respond when there is nothing to grab on to? As long as Feser himself defines the meaning of this “broadly Aristotelian view,” he will always be correct. This does not take us very far.

End quote. Seriously, what is it with Ellmers’ obsession with identifying texts and authors? I imagine that if you said to him: “Glenn, since all men are mortal and Socrates is a man, it follows that Socrates is mortal. Isn’t that a sound argument?” he would respond: “Well, I don’t know about that. Exactly who gave the argument? We don’t really know if it was Socrates, because he didn’t write anything. Unless you tell me who said that and where, I don’t have anything to grab on to.”

In reality, of course, the argument is sound, and who gave it when and where is completely irrelevant. Similarly, the notion of teleology that I was discussing either corresponds to something in reality or it does not, and the arguments for it are either sound or unsound, regardless of who gave them and where and when they gave them. Ellmers should be focusing on those issues, rather than wasting time looking for scholarly footnotes.

The one thing that Ellmers has to say by way of a substantive response is anti-climatic. He writes:

The teleology Feser attributes to unformed matter and chemical compounds – a view that finds no support in Aristotle’s writings – “involves nothing more than a cause’s being ‘directed’ or ‘aimed’ toward the generation of a certain kind of effect or range of effects.” This just means that a cause has an effect. It is a tautology.

End quote. Put aside the irrelevant question of whether Aristotle himself thought of teleology this way. Put aside also the claim that I attribute this teleology to unformed matter (something I didn’t say). The “tautology” charge shows just how out of his depth Ellmers is.

Take any claim of the form “A is the efficient cause of B.” Some Aristotelians, such as Thomists, hold that the only way to account for why A generates B, specifically (rather than C or D or no effect at all) is to hold that A is inherently directed toward the generation of B. This entails a kind of necessary connection between A and B. In this way, efficient causation is, according to the view in question, unintelligible without final causation. Some recent analytic philosophers have argued for a similar position. By contrast, philosophers influenced by David Hume deny this. They hold that there is no directedness in nature, and that the connection between causes and effects is “loose and separate” rather than necessary.

Indeed, other early modern philosophers also rejected the notion of teleology in question, on the grounds that directednesscan (they claimed) only be a feature of minds and not of unconscious inorganic phenomena. And in fact, even earlier than that, followers of Ockham were questioning the reality of necessary causal connections in nature. The two sides in this dispute differ over what is entailed by the claim that “a cause has an effect” (to use Ellmers’ phrase). For one side, this entails teleology and necessary connection, and for the other side it does not.

The point is this. The dispute over teleology of the kind at issue is substantive. That’s why there’s a dispute. The early modern and contemporary philosophers who reject the notion of teleology in question don’t say “Sure, the directedness you’re talking about is real, but that’s just an uninteresting tautological point.” Rather, they say that it is not real.

Another mark of how substantive the dispute is is the ripple effect it has had on other philosophical issues. For example, it is the reason why the intentionality of the mental became such a big problem for modern materialism. If there is no directedness anywhere in the natural world, then how can the mind’s intentionality (its directedness toward an object) be identified with or explained in terms of natural processes? Again, the reason there is a problem is precisely because materialists don’t say “Sure, there’s directedness in all material processes, but that’s just an uninteresting tautology.” Rather, they say that there is no directedness in the material world (or that what seemsto be directedness can be analyzed away or reduced to something that involves no directedness).

Here’s another thing. All of this is discussed in my book. Which indicates, once again, that Ellmers didn’t read it very carefully, or perhaps simply didn’t understand it. If he had, he would have realized that the “tautology” charge at best begs the question and at worst simply misses the point.

Ellmers also remarks that “a thoughtful debate about this question would have involved the metaphysical basis of natural right.” But yet again, this just shows Ellmers’ fixation on trying to tie my book to the issues he personally cares about, even if they are not what the book itself is about. Is teleology relevant to the question of the metaphysical basis of natural right? You bet it is. Is the topic of the metaphysical basis of natural right interesting and important? You bet it is.

But it is also true that you can say a lot about teleology without getting into that particular application of the concept, and a lot of what you can say about it is interesting and important in its own right. And it is these other issues that are the subject matter of Aristotle’s Revenge.

Not every book has to be about Glenn Ellmers’ favorite topics. The fact that Ellmers can’t seem to blow his nose without addressing its relevance to the metaphysical basis of natural right doesn’t entail that the rest of us have to follow suit.

Published on September 13, 2019 11:58

No comments have been added yet.

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 332 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.