Gage on Five Proofs

I’ve been getting some strange book reviews lately. First up is Logan Paul Gage’s review of my book

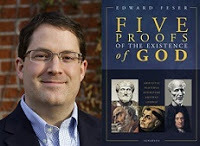

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

in the latest issue of Philosophia Christi. Gage says some very complimentary things about the book, for which I thank him. He also raises a couple of important points of criticism, for which I also thank him. But he says some odd and false things too. Let’s take these in order. Gage writes that Five Proofs is “an incredibly useful book,” that “Feser is to be commended for interacting with a wide swath of historical and contemporary literature,” and that my main arguments are “thorough enough for philosophers while remaining accessible to a general audience – a true accomplishment.” He judges that:

I’ve been getting some strange book reviews lately. First up is Logan Paul Gage’s review of my book

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

in the latest issue of Philosophia Christi. Gage says some very complimentary things about the book, for which I thank him. He also raises a couple of important points of criticism, for which I also thank him. But he says some odd and false things too. Let’s take these in order. Gage writes that Five Proofs is “an incredibly useful book,” that “Feser is to be commended for interacting with a wide swath of historical and contemporary literature,” and that my main arguments are “thorough enough for philosophers while remaining accessible to a general audience – a true accomplishment.” He judges that:[T]he major arguments are incredibly well-executed and likely sound. The first five chapters will be profitable for undergraduates for years to come. They are suitable for use in the classroom, especially for elucidating difficult primary texts. They will introduce students not only to the arguments (and their attendant metaphysics) but also let them see how traditional natural theology entails a number of important divine attributes – something sadly missing from much contemporary apologetics.

End quote. Again, I thank Gage for his very kind words.

Some useful points of criticism

Let’s turn to Gage’s useful points of criticism. For one thing, Gage wonders whether my arguments might be too dependent on specifically Aristotelian-Thomistic (A-T) metaphysical premises. He doesn’t claim that these premises are false or implausible, but merely worries that they might make my arguments less attractive to some readers, and that they require a deeper defense than I provide in the book.

In response I would say the following. First, the extent to which my arguments depend on A-T premises varies from argument to argument. For example, the Aristotelian proof is obviously more dependent on them than the rationalist proof is. Moreover, sometimes it is not the argument itself that presupposes A-T metaphysical premises, but rather some particular reply to a criticism of the argument that does so. This might seem a pedantic and irrelevant distinction, but it is not.

Hence, suppose that some reader is initially convinced by an argument from contingency that appeals to the Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR) but makes no reference to any specifically A-T premises. Suppose the reader is then presented with various objections to the argument, such as the suggestion that it is the world itself rather than God that is the necessary being, or such as a challenge to PSR. An A-T philosopher might reply to such objections in a way other philosophers would not. For example, he might say that the world cannot be a necessary being because it is a compound of actuality and potentiality rather than pure actuality. Or he might defend PSR by reference to the Scholastic idea that truth is convertible with being, so that whatever has being must be intelligible. Now, if the reader in question rejects A-T philosophy and thus rejects these particular responses to the criticisms in question, it doesn’t follow that he will have to reject the argument from contingency. For he might still find some other responses to the criticisms to be adequate.

All the same, it has long been my own view that at least some specifically A-T metaphysical premises are, ultimately, crucial to getting things right in natural theology. For example, I think that the theory of actuality and potentiality is crucial. But then, I think the theory of actuality and potentiality is, ultimately, crucial to getting things right in philosophy in general, not just in natural theology. So, I would acknowledge that, at the end of the day, my view is that the natural theologian should defend such specifically A-T premises. But I don’t see that as a problem. If something is both true and highly consequential, as I think the theory of actuality and potentiality is, then there’s no point in fretting that it will be a tough sell with many people. It needs to be defended, so defend it.

Indeed, as I have complained before, a general problem with too much apologetics is that it is excessively concerned with what will “sell” rather than with what is true. My view is that, just as a matter of principle, a serious apologist should focus on the latter rather than the former. And it turns out that if you do that, and do it well, the former will take care of itself.

Gage is also right to say that more could be said in defense of the A-T premises I appeal to than I say in Five Proofs. That was inevitable given that the book is about natural theology rather than general metaphysics, and given that, in philosophy, no matter what and how muchyou say, there is always going to be someone somewhere who retorts “Well, sure, but what about…” Of making books there is no end. But as it happens (and as Gage acknowledges) I have in fact defended the relevant general A-T premises in greater depth elsewhere, such as in my book Scholastic Metaphysics .

A second important point of criticism raised by Gage is that it isn’t clear, in his view, that all of my arguments are really independent of one another. In particular, he worries that the four proofs that reason from the world to God as cause of the world – the Aristotelian proof, the Neo-Platonic proof, the Thomistic proof, and the rationalist proof – are really just variations on an argument from contingency rather than separate standalone arguments. For example, he wonders whether the Aristotelian proof is really at the end of the day an argument from change, since the way I spell that argument out, it shifts from the question of why things change to why they exist at any given moment.

In response, I would say the following. First, though the “many paths up the mountain” analogy is often abused in theological contexts (when deployed in defense of a facile universalism), it is useful in understanding the relationship between causal proofs of God’s existence. When you get to the top of a mountain, it looks pretty much the same, whatever direction you are approaching it from. But the north side of the bottomof the mountain might nevertheless look very different from the south side, so that the mountain will seem very different to climbers beginning from the north side and climbers beginning from the south.

In the same way, the notions of what is purely actual, what is absolutely simple, what is subsistent existence itself, and what is absolutely necessary are all at the end of the day (I would argue) different ways of conceptualizing what is and must be the same one reality. Hence the closer you get to the conclusion of a causal argument for God’s existence, the more the argument is going to seem similar to other causal arguments. Nevertheless, the starting points – the fact that things in our experience change, the fact that they are composite, the fact that they are caused, the fact that they are contingent – are going to be very different.

Now, this is important in a way that is also elucidated by the mountain analogy. Some climbers who may be unable or unwilling to begin their ascent from one side of the mountain (because it is too rocky for them, say) may be able to begin it from some other side. Similarly, some readers may initially find the notions of contingency or of PSR problematic and thus be put off by the rationalist proof, but find intuitively plausible the notion of change as the actualization of potential, and thus find the Aristotelian proof attractive. At the end of the day, I think readers should find all of these things plausible when they are rightly understood, but given the place some particular reader is coming from philosophically, he might have a different “break in” point from other readers. So even if the proofs converge, it is intellectually helpful to see that there are different conceptual avenues by which the idea of a divine first cause might be arrived at.

Having said that, I also think that the extent to which the proofs converge can be overstated. As my remarks above indicate, I think that one can go a long way in an argument from PSR before one has to get into any distinctively Aristotelian notions like the actualization of potential. And I think one can go a long way in an Aristotelian proof before one has to say anything that sounds distinctively “rationalist.” In these two cases, it is arguably only when one has to get into the question of how various objections might be replied to that defenders of the arguments might end up saying some of the same things.

In the case of the Aristotelian proof, it is true that I make a transition from the question of why things change to the question of why they exist at any given moment, and that it is the latter question that I am ultimately more interested in. This makes my presentation of this sort of argument different from Aristotle’s or Aquinas’s presentation. (That’s one reason I call it an “Aristotelian proof” rather than “Aristotle’s proof.”) But there is a reason why I begin with change, which is that the notions of actuality and potentiality are much easier to grasp initially when one applies them to an analysis of change overtime than when one applies them to an analysis of existence at a time. The latter notion is for many readers too abstract to jump to immediately. So, starting with change provides a useful “ladder” that may be kicked away once one understands the general concepts and sees that they have a more general application than just to the analysis of change.

Anyway, I agree with Gage that other interpretations of the arguments I defend are possible, and that it would be regrettable if those other interpretations were neglected. And again, I thank him for these remarks, to which I have responded at some length precisely because the issues he raises are important.

Seeing things that aren’t there

Let’s turn now to (what I judge to be) the odd and unhelpful things Gage has to say. Gage accuses the book of “some exasperating flaws.” Like what? First of all, he claims that the book includes “some of Feser’s favorite hobbyhorses.” Like what? Gage writes:

Conspicuously absent from the first five chapters are Feser’s constant refrains: how impressive traditional theistic arguments are for being deductive metaphysical demonstrations rather than probabilistic or scientific arguments (in which he fails to recognize the power of inductive and abductive arguments), tangents about how foolish William Paley and intelligent design are (with uncharitable misreadings of these potential allies), and his blog-style ranting and braggadocio – often against weak targets like the worst of the New Atheists. But they all return by the book’s end (271-273, 287-289, 249-260), leaving a bitter aftertaste to a largely excellent book. The whole thing concludes with an unhelpful and supercilious “Quod erat demonstrandum” (307).

End quote. Now, I fail to see what the big deal is about ending the book with “Quod erat demonstrandum” – especially given that Gage himself says he regards my main arguments as “incredibly well-executed and likely sound” – but let that pass. The rest of this is just silly and false.

First of all, it simply isn’t true that the book describes Paley or Intelligent Design as “foolish.” I mention Paley in exactly two places in the book, at pp. 287-88 and at p. 303. In the first place, I merely note that the arguments I am defending are in several ways different from Paley’s design argument. In the second place, I merely cite Paley in a long list of philosophers who have defending theistic arguments. I also mention Intelligent Design theory in exactly two places in the book, at p. 254 and at pp. 287-88. In the first place, I merely note that atheists who raise a certain sort of objection against first cause arguments would complain if a parallel objection were raised against evolution by ID theorists. In the second place, I merely note that the arguments I am defending differ in several ways from the arguments of ID theorists. I mention inductive or probabilistic arguments for God’s existence at exactly two places, at pp. 287-88 and at p. 306. In both cases I merely note that the arguments I am defending are not of the inductive or probabilistic kind, but rather are attempts at demonstration.

Nowhere in the book do I say that Paley, or ID theory, or probabilistic arguments are “foolish.” Indeed, I do not even say in the book that they are wrong. Again, I merely note that they are different from the sorts of arguments I defend in the book. That’s it.

It’s not mysterious what is going on here, though. For I have, in other writings, been very critical of Paley and of Intelligent Design theory. I have also, in other writings, made it clear that I much prefer demonstrations to probabilistic arguments where natural theology is concerned (though I have also explicitly said that I do not claim that probabilistic arguments for God’s existence are per seobjectionable).

Now, Gage is a big defender of Paley, ID, and probabilistic arguments for God, and he and I have tangled over these very issues in the past. Evidently, this past experience has colored Gage’s perceptions of what he has read in Five Proofs. He is apparently so sensitive about criticisms of Paley, ID, and probabilistic theistic arguments that he cannot bear even my distinguishing A-T arguments from those sorts of arguments. All he needs is to see that the words “Paley” or “Intelligent Design” or “probabilistic” appear in something I have written, and he is triggered. He instantly takes my remarks in Five Proofs to be criticisms of these things, even though when read dispassionately it is clear that they are not. So, while there is definitely some “hobbyhorse” riding going on, it is all on Gage’s part, not mine.

Something similar can be said about Gage’s claim that Five Proofs contains “blog-style ranting and braggadocio.” The astute reader will have noted that Gage offers no examples of this purported ranting and braggadocio – and he couldn’t have, because in fact there isn’t any such thing to be found in Five Proofs. That is deliberate, because I judged that a polemical style was not appropriate given the aims of this particular book.

What is true is that in other writings, I have sometimes (though in fact only relatively rarely) written in a highly polemical style. For example, of the twelve books I have written, co-written, or edited, there is exactly one – The Last Superstition – that is written in that style. And occasionally I will write an article, book review, or blog post in that style – typically when responding to some other writer who was himself highly polemical.

I have in other placesdefended the appropriateness of this approach under certain circumstances. The point for present purposes is this. I have found over the years that certain souls seem to be so gentle and sensitive that they just can’t bear this sort of thing even when it is appropriate. My occasionally polemical style makes such a deep impression on them that they simply can’t help but perceive everything I write as “blog-style ranting and braggadocio.” This is especially true when my past targets have included some of their own sacred cows.

It seems that something like this is going on with Gage. My past polemical writings, perhaps especially those in which I have criticized ID, have colored his perceptions. Hence though the arguments and objections I present in Five Proofs are measured in tone, he reads into them a “blog-style ranting and braggadocio” that isn’t there.

Some odd and unhelpful criticisms

The really strange remarks Gage makes, though, are about the last two chapters of my book – chapter 6, which treats the divine attributes and God’s relationship to the world, and chapter 7, which is a general treatment of objections to natural theology.

What annoys him about chapter 6 is that there is some repetition of material from earlier chapters, since after presenting each of my five theistic arguments in the earlier chapters, I say something about how the divine attributes can be derived. Gage thinks that I should either have said nothing about the divine attributes in chapters 1-5 and saved the entire discussion for chapter 6, or that I should have moved all the material from chapter 6 into the earlier chapters.

It never seems to have occurred to Gage that I had a reason for organizing things the way I did – several reasons, in fact. Here are some of the relevant considerations. First, one of the objections routinely raised against arguments for God’s existence is that even if they get you to a first cause, no one has ever shown that they get you to a cause that is unique, omnipotent, omniscient, etc. There is, it is claimed, always a big jump from the idea of a first cause to the divine attributes. Now, as I show in Five Proofs and elsewhere, that is simply not at all the case. Aristotle, Aquinas, Leibniz, and other defenders of proofs for God’s existence in fact routinely provide a wealth of argumentation for the divine attributes. But, as with the tiresome and clueless “What caused God?” objection, people keep reflexively raising this objection no matter how many times you refute it.

Consider also that many readers will only bother reading a chapter or two from a book like mine before drawing general conclusions about it. Hence if they read the chapter on the Aristotelian proof but do not see in it any treatment of the divine attributes, they will judge that I have overlooked the obvious objection that to prove the existence of a purely actual actualizer is not to prove that such an actualizer is unique, omnipotent, omniscient, etc. And they will conclude that it isn’t worth their time to read any further. This is silly, of course, and not the way an academic philosopher like Gage or me would proceed. But it is the way a lot of people read and judge books.

Consider too that there are certain divine attributes the derivation of which is more clear and natural when one begins with a particular theistic proof than it is when one begins with some other such proof. For example, when you deploy the Aristotelian proof to establish the existence of a purely actual actualizer, it is quite natural to move on immediately to argue for the immutability, omnipotence, and perfection of the purely actual actualizer. The reason is that the theory of actuality and potentiality provides analyses of change, causal power, and perfection that can be quite naturally “plugged in” to the argument to yield a derivation of these particular divine attributes. The derivation of the attributes isn’t some arbitrary “add on” to the proof of the unactualized actualizer, but follows quite naturally and directly from it. But the same attributes are less directly or obviously derivable from, say, the notion of the necessary being that is arrived at via the rationalist proof.

So, given considerations like these, I judged that the best way to proceed would be to say something in each of the first five chapters about how the derivation of a purely actual actualizer, an absolutely simple cause, an infinite intellect, a cause which is subsistent existence itself, and an absolutely necessary being, could naturally be extended to a derivation of some of the key divine attributes. The aim was to show that getting to the divine attributes is an organic partof the style of reasoning that each of the arguments deploys, and not something either neglected or arbitrarily tacked on.

At the same time, I couldn’t say everything that needed to be said about the divine attributes in each of the first five chapters, or even in any one of them, because the chapters would in that case have become ridiculously long. For example, if I had placed the material on the divine attributes from chapter 6 into chapter 1, which is devoted to the Aristotelian proof, then chapter 1 would have been about 120 pages long. It would also have ended up dealing with matters that are not unique to the Aristotelian proof, but are relevant to all the proofs.

Hence I judged that the better way to proceed was to give a cursory treatment of the divine attributes in chapters 1-5, and then return to a much more in-depth treatment in chapter 6. This entailed a bit of repetition, but as every good teacher knows, a bit of repetition is not necessarily a bad thing, especially when giving an exposition of material that is difficult and unfamiliar. And the arguments for the divine attributes are – as Gage himself acknowledges – very unfamiliar to many people interested in the topic of arguments for God’s existence.

So, though of course a reasonable person might disagree with my judgment, there were reasons for it that Gage does not consider. The way the book handles the divine attributes was deliberate, and not, contrary to what he suggests, a failure on the part of some editor. Gage seems to be the sort of reviewer who complains that a book is not carefully tailored to his personal needs and interests, specifically – not keeping in mind that any book has to consider the needs, interests, attention spans, prejudices, etc. of many kinds of readers all at once. And of course, no book can do so perfectly, so that an author must make a judgment call. Anyway, as far as I can recall, Gage is the only commenter on the book who has complained about there being a bit of repetition on the topic of the divine attributes. Evidently, most readers were not troubled by it.

Gage also complains that chapter 6 includes a “digression on analogy,” a “misconstrual of the standard account of knowledge,” a “facile discussion of God’s knowledge and free will,” and a “defense of using male pronouns for God.” He says that this material only “serves to try the reader’s patience.”

But once again, Gage seems to be confusing hispersonal needs and interests with those of readers in general. He doesn’t tell us exactly what is wrong with what I say about knowledge or free will, so I don’t have anything to say in response to his remarks about those topics. As far as my treatment of analogy is concerned, it is by no means a “digression,” but integral to the chapter. I made it clear in the book why (for Thomists, anyway) the notion of analogy is crucial to a proper understanding of the divine attributes.

Regarding the use of male pronouns for God, I have no idea why Gage would find it objectionable that I should address that issue. As I imagine everyone knows who has ever taught a course on religion or philosophy of religion, it is a question that comes up all the time among students, and general readers are no less interested in it. Furthermore, such language is crucial in certain theological contexts (e.g. when the first two Persons of the Trinity are referred to as the “Father” and the “Son”). If Gage wants to disagree with the specific claims I made on this topic, that’s fine. But to object to the very fact that I addressed the issue at all is silly, indeed bizarre.

Finally, Gage is similarly unhappy with my last chapter, wherein I deal with a wide variety of general objections to arguments for God’s existence. He complains, for example, that I respond to “weak targets like the worst of the New Atheists.” But why is this a problem? For one thing, I also respond, in the last chapter and throughout the book, to the more serious critics. It’s not as if I reply only to the New Atheists. For another, what was I supposed to do – ignore the objections raised by the New Atheists? Gage and I realize that their objections are no good, but lots of other readers don’t realize this, and many of those other readers will be unfamiliar with what I have said in reply to the New Atheists in other books of mine, such as The Last Superstition. Moreover, their objections, however feeble, are very influential. So, I had no choice but to address their objections, alongside the more serious objections. Yet again, Gage seems guilty of judging the book in terms of his personal needs and interests, rather than those of the bulk of the book’s readership.

But as I have said, Gage also makes some important and helpful points of criticism, and has some very kind things to say about my book. And even where I think his remarks are unreasonable, I appreciate his attempt to grapple seriously with what I have written. So, again, I thank him.

Published on August 30, 2019 16:44

No comments have been added yet.

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 332 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.