The smaller generation to come – worldwide

Here’s some good news for the planet: the human population is set to peak and stabilise, not rising much above 9.7 billion, the total that it will reach around the year 2050, according to the latest UN figures. Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography at Oxford University, explains how this works, and why it is something to celebrate.

On Monday 17 June 2019 the United Nations revealed momentous news. The world did not notice, but soon it will. The headline of their own report read “9.7 billion on Earth by 2050, but growth rate slowing”.

A day earlier the UN projection for the year 2050 had been nearer 9.8 billion, and the projection for 2100 had been 11.2 billion people. Something very significant had occurred.

Some parts still growing, but…

The United Nation’s report concentrated on where there will still be the most growth. To quote: “India is expected to show the highest population increase between now and 2050, overtaking China as the world’s most populous country, by around 2027. India, along with eight other countries, will make up over half of the estimated population growth between now and 2050. The nine countries expected to show the biggest increase are India, Nigeria and Pakistan, followed by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Indonesia, Egypt and the United States of America.”

But their report continued: “The population size of more and more countries is actually falling. Since 2010, 27 countries or areas have seen a drop of at least one per cent, because of persistently low fertility rates. Between now and 2050, that is expected to expand to 55 countries which will see a population decrease of one per cent or more, and almost half of these will experience a drop of at least 10 per cent.”

Bellwether 18-year-olds

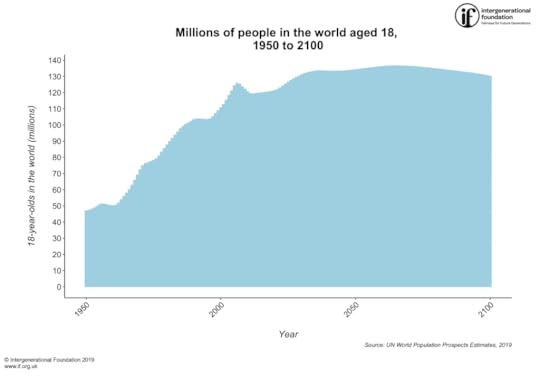

The UN did not mention their new 2100 prediction in this particular press release. The first graph below shows the number of people the UN estimate have been (and will be) aged 18 each year from 1950 until 2100. The future they predict is remarkably smooth.

The number of 18 year olds in the world – UN world population prospects estimates, 2019 (millions of people aged 18, 1950 to 2100)

However, some reporters noticed that something was very new: “The world’s population is slowing down and could stop growing – or even begin decreasing – by 2100” one noticed, before adding that “…[UN population] division director John Wilmoth said this outcome ‘is not certain and in the end the peak could come earlier or later, at a lower or higher level of total population.’”

However, John’s central projection for the year 2100 is now 10.9 billion people, 300 million fewer than the UN said they expected, the day before.

Even fewer babies – but longer lives

Human population growth is slowing dramatically and it is slowing because people are having fewer and fewer babies as compared to their parents – everywhere – without exception.

More importantly, they are having fewer than we thought they would have a few years ago when the fertility rates were already reducing dramatically and unprecedentedly. Our species has never – ever – had so few children.

The reason why the total human population of the planet will keep on growing for 50, or 60 or 70 years (but almost certainly not for 80 years) is because people are living longer. It is now no longer because we are having more children.

If people in a particular place live for 80 years rather than 40 (on average), they double the number of people found in that place at any one time without a single additional baby needing to be born.

The human species is ageing – rapidly. More rapidly than we thought it was by Monday 17 June 2019! And this is wonderful news because it is caused by fewer people dying when young and healthcare for the elderly improving.

Tell-tale peaks for 18-year-olds

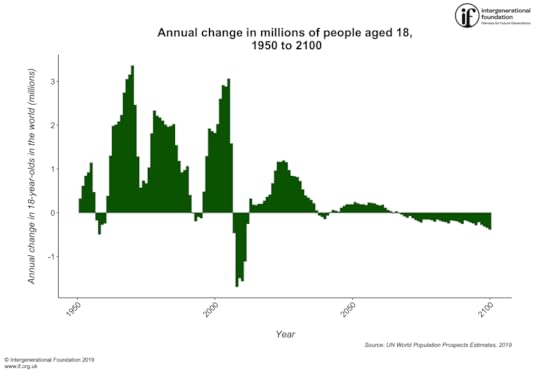

The next graph below shows the annual change in the number of 18-year-olds now predicted to occur each year and the number that did occur each year in the last 68 years. The peaks in the graph below occurred in 1955, 1970, 1985 and 2005, with the next predicted to be in 2025. The length of time between these peaks in years is 15, 15, 20 and 20.

The number of 18 year olds in the world – UN world population prospects estimates, 2019 (annual change in millions of people aged 18, 1950 to 2100)

It is the trend in the corrections to the UN revisions that matters most. In the 2011 estimates the UN demographers suggested that 10 billion was most likely by 2100. The subsequent 2013, 2015 and 2017 revisions updated that estimate to just over 11 billion. But now the 2019 revision is reducing that estimate again.

Six years ago, on 11 June 2013, I published a book titled Population 10 billion in which I made a guess that the UN were getting it wrong. It was just a guess, but it turned out to be right. The reason they were making this mistake, I said, is that they had failed to notice an echo of a baby boom. They were using very current fertility estimates to project forwards, unaware that fertility at the start of this current century was slightly and unusually elevated – due to so many people turning 18 around the year 2005.

(Non-robotic) implications for smaller generations

The slowdown in the growth and then the fall to come in young adults worldwide raises all kinds of issues. In general, smaller generations have been more powerful generations in the past. Their bargaining position is better. Each child becomes more precious.

But in strange times like these, people begin to try to imagine all kinds of new scenarios. However, “artificial intelligent” robots are not going to replace the young. The reason why is simple. We are an animal, evolved to be acutely aware of just how much attention we are or are not getting from others of our species. That is how for millennia those of us that survived, survived. We were cared for, and cared for our young. Most of us are acutely aware of even the smallest slight we receive, the mildest of ignoring. Most of us warm with happiness when we are praised by those we love. Emulating humans to fool other humans with machines is a fools’ game because it is trying to compete with what drove our evolution. Instead, robots are best used to undertake repetitive tasks that our inquisitive nature hates.

Predictions in a precarious world

What is likely to happen next? Look again at the graph above of the future change in the number of 18-year-olds predicted to carry through to the year 2100. Note how the UN prophesies a rapid move towards stability. To achieve that, every 18-year-old has to have slightly more than two children each (because a few babies will still die even in the most utopian of futures).

But then look at what has happened most recently. Look at the falls between 2007 and 2013 in the graph above and note how that plummeting below the line almost exactly fits the gap that can be seen in the time series between 1991 and 1996, around 17 years earlier.

Young adults in future are unlikely to conform to what the UN demographers currently predict. If we manage to avoid world war, famine, pandemic and severe prolonged global economic crisis, then young people will continue to have fewer and fewer children each – for some time to come. It is what women want. And more and more women now get what they want.

Change in change

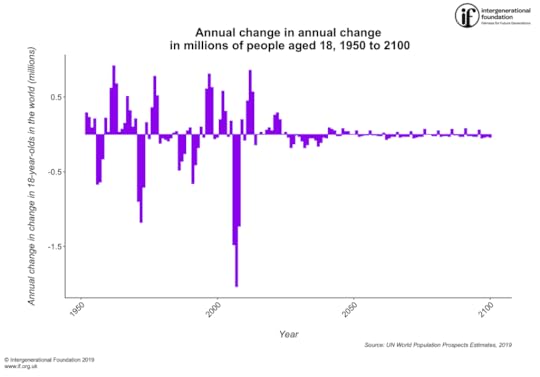

Finally, if you find it hard to believe that the finest demographic minds the world can muster might still be making a mistake, even though they now are at least moving their predictions down toward what reality is telling them, look at the last graph in this series of three, below. The graph shows the “change in change” each year in 18-year-olds.

This is just one change figure subtracted from another. To give an example in 2006, 2007 and 2008 the number of 18-year-olds thought to be alive worldwide on 1 July each year was 125.850, 125.386, and 123.692 million respectively. The change between those three numbers was -0.46 and -1.69 million: the population was falling, and the change in change between those two numbers, the rate of deceleration or acceleration, was -1.23 million – a rapid deceleration (or acceleration in the rate of fall if you want to see it that way).

The final graph below shows all of those “change in change” figures derived from the very latest UN population estimates for the world. Each great deceleration – the troughs in 1955, 1972 and 2007 – has been greater in magnitude than the last.

Now look at what the UN think will happen in future and then start planning for even fewer 18-year-olds than they are now suggesting there will be. Because they are still ignoring this clear downwards trend.

The number of 18 year olds in the world – UN world population prospects estimates, 2019 (annual change in change,,millions of people aged 18, 1950 to 2100)

Web links:

https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/06/...

https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/na...

https://population.un.org/wpp/

http://www.dannydorling.org/books/10b...

http://www.dannydorling.org/books/dem...

Why Demography Matters

Danny Dorling & Stuart Gietel-Basten

Why Demography Matters?

http://www.dannydorling.org/books/dem...

For a PDF for this article and an on-line link to the original posting click here.

A talk to school children in London the day after the UN released its latest biannual global population estimates: demography and what else we worry about in the very near future…

Danny Dorling speaking at Channing Senior School and to pupils from neighbouring schools, London, Archway, June 20th 2019

World population – United Nations 2019 revision – people aged 18, estimated and projected

18 year olds

thousands

millions

Change

Change in Change

1950

47 028

47

1951

47 351

47

0.32

1952

47 963

48

0.61

0.29

1953

48 802

49

0.84

0.23

1954

49 725

50

0.92

0.09

1955

50 863

51

1.14

0.21

1956

51 332

51

0.47

-0.67

1957

51 165

51

-0.17

-0.64

1958

50 673

51

-0.49

-0.33

1959

50 403

50

-0.27

0.22

1960

50 164

50

-0.24

0.03

1961

50 547

51

0.38

0.62

1962

51 848

52

1.30

0.92

1963

53 831

54

1.98

0.68

1964

55 839

56

2.01

0.03

1965

57 915

58

2.08

0.07

1966

60 142

60

2.23

0.15

1967

62 879

63

2.74

0.51

1968

65 933

66

3.05

0.32

1969

69 085

69

3.15

0.10

1970

72 444

72

3.36

0.21

1971

74 906

75

2.46

-0.90

1972

76 187

76

1.28

-1.18

1973

76 758

77

0.57

-0.71

1974

77 489

77

0.73

0.16

1975

78 158

78

0.67

-0.06

1976

79 190

79

1.03

0.36

1977

81 000

81

1.81

0.78

1978

83 330

83

2.33

0.52

1979

85 544

86

2.21

-0.12

1980

87 711

88

2.17

-0.05

1981

89 811

90

2.10

-0.07

1982

91 823

92

2.01

-0.09

1983

93 781

94

1.96

-0.05

1984

95 762

96

1.98

0.02

1985

97 778

98

2.02

0.04

1986

99 315

99

1.54

-0.48

1987

100 490

100

1.18

-0.36

1988

101 409

101

0.92

-0.26

1989

102 382

102

0.97

0.05

1990

103 441

103

1.06

0.09

1991

103 842

104

0.40

-0.66

1992

103 835

104

-0.01

-0.41

1993

103 648

104

-0.19

-0.18

1994

103 563

104

-0.09

0.10

1995

103 438

103

-0.12

-0.04

1996

103 921

104

0.48

0.61

1997

105 212

105

1.29

0.81

1998

107 131

107

1.92

0.63

1999

108 995

109

1.86

-0.06

2000

110 814

111

1.82

-0.04

2001

112 832

113

2.02

0.20

2002

115 431

115

2.60

0.58

2003

118 338

118

2.91

0.31

2004

121 214

121

2.88

-0.03

2005

124 273

124

3.06

0.18

2006

125 850

126

1.58

-1.48

2007

125 386

125

-0.46

-2.04

2008

123 692

124

-1.69

-1.23

2009

122 202

122

-1.49

0.20

2010

120 638

121

-1.56

-0.08

2011

119 525

120

-1.11

0.45

2012

119 270

119

-0.25

0.86

2013

119 589

120

0.32

0.57

2014

119 765

120

0.18

-0.14

2015

119 939

120

0.17

0.00

2016

120 140

120

0.20

0.03

2017

120 344

120

0.20

0.00

2018

120 611

121

0.27

0.06

2019

120 972

121

0.36

0.09

2020

121 379

121

0.41

0.05

2021

122 050

122

0.67

0.26

2022

123 013

123

0.96

0.29

2023

124 176

124

1.16

0.20

2024

125 341

125

1.16

0.00

2025

126 532

127

1.19

0.03

2026

127 685

128

1.15

-0.04

2027

128 655

129

0.97

-0.18

2028

129 494

129

0.84

-0.13

2029

130 327

130

0.83

-0.01

2030

131 133

131

0.81

-0.03

2031

131 849

132

0.72

-0.09

2032

132 382

132

0.53

-0.18

2033

132 775

133

0.39

-0.14

2034

133 116

133

0.34

-0.05

2035

133 406

133

0.29

-0.05

2036

133 617

134

0.21

-0.08

2037

133 665

134

0.05

-0.16

2038

133 605

134

-0.06

-0.11

2039

133 510

134

-0.09

-0.04

2040

133 366

133

-0.14

-0.05

2041

133 308

133

-0.06

0.09

2042

133 319

133

0.01

0.07

2043

133 384

133

0.06

0.05

2044

133 424

133

0.04

-0.02

2045

133 447

133

0.02

-0.02

2046

133 554

134

0.11

0.08

2047

133 706

134

0.15

0.04

2048

133 893

134

0.19

0.04

2049

134 080

134

0.19

0.00

2050

134 267

134

0.19

0.00

2051

134 503

135

0.24

0.05

2052

134 713

135

0.21

-0.03

2053

134 907

135

0.19

-0.02

2054

135 095

135

0.19

-0.01

2055

135 269

135

0.17

-0.01

2056

135 497

135

0.23

0.05

2057

135 714

136

0.22

-0.01

2058

135 920

136

0.21

-0.01

2059

136 105

136

0.18

-0.02

2060

136 264

136

0.16

-0.02

2061

136 441

136

0.18

0.02

2062

136 547

137

0.11

-0.07

2063

136 603

137

0.06

-0.05

2064

136 632

137

0.03

-0.03

2065

136 627

137

-0.01

-0.03

2066

136 655

137

0.03

0.03

2067

136 644

137

-0.01

-0.04

2068

136 599

137

-0.04

-0.03

2069

136 522

137

-0.08

-0.03

2070

136 410

136

-0.11

-0.03

2071

136 338

136

-0.07

0.04

2072

136 213

136

-0.12

-0.05

2073

136 050

136

-0.16

-0.04

2074

135 861

136

-0.19

-0.03

2075

135 638

136

-0.22

-0.03

2076

135 490

135

-0.15

0.07

2077

135 343

135

-0.15

0.00

2078

135 193

135

-0.15

0.00

2079

135 019

135

-0.17

-0.02

2080

134 820

135

-0.20

-0.02

2081

134 674

135

-0.15

0.05

2082

134 498

134

-0.18

-0.03

2083

134 303

134

-0.20

-0.02

2084

134 091

134

-0.21

-0.02

2085

133 850

134

-0.24

-0.03

2086

133 684

134

-0.17

0.07

2087

133 509

134

-0.18

-0.01

2088

133 319

133

-0.19

-0.01

2089

133 101

133

-0.22

-0.03

2090

132 850

133

-0.25

-0.03

2091

132 678

133

-0.17

0.08

2092

132 483

132

-0.19

-0.02

2093

132 267

132

-0.22

-0.02

2094

132 023

132

-0.24

-0.03

2095

131 747

132

-0.28

-0.03

2096

131 533

132

-0.21

0.06

2097

131 266

131

-0.27

-0.05

2098

130 957

131

-0.31

-0.04

2099

130 617

131

-0.34

-0.03

2100

130 240

130

-0.38

-0.04

Danny Dorling's Blog

- Danny Dorling's profile

- 96 followers