Documenting the science of change

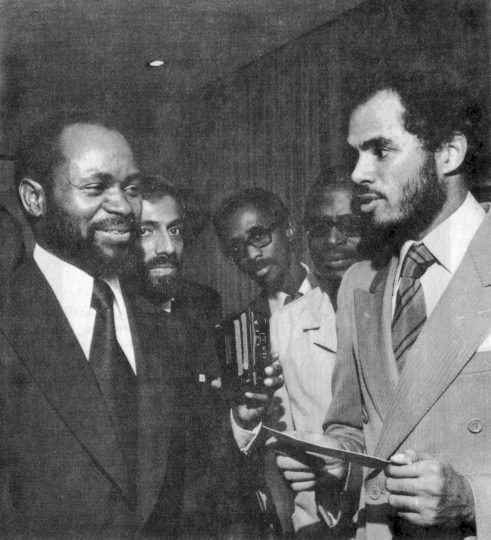

Samora Machel and Robert Van Lierop at the United Nations in 1977. Photo courtesy of Robert Van Lierop, credit Machel Van Lierop via the African Activist Archive.

A��dark-skinned man in fatigues��tiptoes across a��log��amidst dense��forest, automatic machine gun slung over his shoulder.��A��South African accented voice reports with��news anchor���s smoothness on the 1971 uprising in��New York���s��Attica prison. Armed men and women wade through��a��stream as��the��voiceover��shifts to discuss��the��expansion��of��the��liberation wars in Southern Africa. This is how��African��American��filmmaker��Robert Van��Lierop��introduces��the��audience to��FRELIMO��(Frente��da��Liberta����o��de��Mo��ambique, or Mozambique Liberation Front),��in his��1972��documentary,��A Luta Continua��(The Struggle Continues). These��soldiers��are��fighting��the Portuguese military for control��of��Mozambique.��But it���s��clear in the opening scenes that their��struggle��has meaning for��battles��against racism��and exploitation��the world over.

A Luta Continua��was arguably the most important of��a��minor genre of��films produced��on the��liberation struggles��that occurred��in��the Portuguese colonies of��Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea-Bissau��between��1961��and��1975.��Produced mostly by activists, these politically charged documentaries��explored��not just the��dismantling��of��Portuguese colonialism,��but��also��the construction of a��progressive,��socialist��nation��behind the front lines��of revolution.��Battle footage��contrasted��with extended��scenes from collective farms, rural medical centers, and elementary classrooms���semblances of the independent nation that��FRELIMO��fought to achieve.��Narration��explained��how��these seemingly��distant events��revealed��the global nature of��empire and��racial inequality.��By introducing FRELIMO���s socialist freedom struggle��to global audiences,��A Luta Continua��and similar films��aided��the��creation��of��a��transnational��anti-imperial solidarity.

Such solidarity was vital for FRELIMO.��Tiny Portugal waged��a��three-front war for over a decade because it had the��support of the��North Atlantic alliance��and��western��corporations, including Gulf Oil. FRELIMO and its leftist revolutionary allies in Angola and Guinea-Bissau��fought back��with assistance��from neighboring countries Tanzania��and Guinea, as well as material support from further afield��in Africa,��Eastern Europe, and Asia. But leaders��such as��Eduardo��Mondlane���FRELIMO���s American-educated, football loving��president���believed��that winning over��western��countries could weaken Portugal and even the playing field. When��governments in��the United States and Great Britain offered little more��than��token rhetorical support for decolonization, FRELIMO turned to��civil society.��It built relationships with the American Committee on Africa and later the black nationalist African Liberation Support Committee,��and��it��helped launch groups like the British Committee for the Freedom of Mozambique, Angola, and��Guinea��when none emerged organically.��The making of films and their screenings��helped mobilize this popular solidarity by��dramatizing��Mozambique���s��revolution��and��linking��it��with Euro-American struggles.

FRELIMO could not produce its own films��due to limited resources,��so it relied on international allies.��Activists from across the world travelled to��FRELIMO���s��military camps and educational facilities in��southern��Tanzania, as well as the regions of��Mozambique under��the party���s control.��FRELIMO��invited these filmmakers��to see for themselves the revolution��in action, then translate��the��struggle��in ways that engaged��foreign audiences.��They hoped this��footage��would��inspire��solidarity��and offer lessons for��domestic��campaigns��for social justice.��From the early Yugoslavian��Venceremos��(We Shall Win)��(c. 1966)��to Van��Lierop���s��sequel��O��Povo��Organizado��(The People Organized)��(1976)��about Mozambican independence in 1975, FRELIMO���alongside��its��compatriots��in Guinea-Bissau and Angola���collaborated with dozens of filmmakers to internationalize��the��freedom struggles��of��Africa.

Margaret Dickinson���s��Behind the Lines��(1971)��was��the first��activist��film��to target��specifically��western��audiences.��This British production��set the tone��for the emerging genre. It emphasized��the social construction of��an independent state, diverging from both news coverage of military campaigns and��activist films on��the��denigration of life under colonialism��and��apartheid.��Dickinson��had��befriended��Mondlane��in Tanzania��and come to share his vision for a free Mozambique, helping��him write��The��Struggle for��Mozambique��not long before his assassination in 1969.��Seeking to inspire a British��anti-colonial��movement that could undermine the alliance with Portugal and provide material aid to FRELIMO, Dickinson took up the camera��to focus on ���politics in the small scale of daily life… on how Frelimo was changing life in a detailed way already���even without winning the war���in liberated areas.�����In addition to structural improvements in such areas as education and healthcare,��Dickinson emphasized��FRELIMO���s dedication to true social equality, fighting not just��colonial��racism��but the gender discrimination present in both colonial and traditional societies.��These images of women working and fighting alongside men effectively integrated the Mozambican revolution into��the��wider feminist and anti-imperial��movements that roiled the��Euro-American��world in the 1960s.

Van��Lierop���s��A Luta Continua��followed in 1972, named for the phrase��Mondlane��often��used when signing correspondence.��The New Yorker of Surinamese descent��saw in FRELIMO���s revolution lessons for how African Americans could wage their own domestic struggles for��self-determination.��Behind the Lines��was��important,��especially among New Left audiences,��but its European origins meant Pan-African connections were few. With��Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)��photographer Bob Fletcher��as cinematographer, Van��Lierop���s��film��revisited many of Dickinson���s themes but added new insights��particular to black��diasporic��audiences.��Its popularity came from this linkage of the��Mozambican revolution with��struggles��for civil rights and��the Black Power movement���s calls for��socio-political��renewal.��A Luta Continua��revealed in concrete terms the global structures supporting racial inequality and the need for concerted effort to achieve real change.

Van��Lierop��argues��that while armed revolution was implausible in the American or European contexts, blacks could still take inspiration from FRELIMO���in its model of unity, organization,��and the redistribution of local resources to marginalized populations.��The��struggle��is��as much about ���the pencil and the farm hoe��� as the gun; all��are��tools��in revolution.��A Luta Continua��offers��the scene of a FRELIMO member living and training with the students he��teaches��as a contrast to the US example: ���When school is out, the teachers do not go one way, into cars for a trip home to exclusive suburbs, while the students go another way deeper into a ghetto. Instead, they are all part of the same mass movement.�����For Van��Lierop��and FRELIMO, revolution is��not about war so much as changing ���the pattern of life for the people waging the struggle.���

This message resonated not just with black American audiences, but with��many at the time who sought��to��challenge��racist, unjust societies.��A trained lawyer, Van��Lierop��refused to copyright the film,��with the intention that��anyone who could obtain or��reproduce a copy could show it.��A Luta Continua��rarely if ever��appeared in��theaters,��but was viewed widely in the United States and abroad. One��Chicago group��reported��100 screenings��for black, school, and church groups��in��only��12��months. Activists and��even revolutionaries���including FRELIMO���s New York representative,��Sharfudine��Khan���spoke at��showings��to promote action in solidarity with African��liberation, broadly defined.��Solidarity��organizations recruited with the film, and both men and women cited it when arguing for a move toward greater gender equality in the��Black Power��movement. Word of��mouth even places��a copy of the��documentary��in Soweto before the famed student uprising of 1976.

The film���s popularity meant few copies survived repeated screenings and reproduction.��Only a��handful��exist��in archives, including at the��Schomburg��Center where Van��Lierop��donated his papers��and copies of��both��his��Mozambican��films. Fortunately, the broad appeal of the��documentary��meant activists��televised it��in��major��cities like Boston.��That���s where I discovered a copy embedded within WGBH���s 1970s black talk show��Say Brother, which we digitized with Van��Lierop���s��permission and��assistance from the African Activist Archive.��This copy has proliferated on��Youtube��as many have found in it a timeless example of anti-imperial, Pan-African collaboration.

Activists and filmmakers the world over still recall the impact this generation of activists-turned-directors had on them.��Neither obsessed with revolutionary violence nor overwhelmed by systemic inequality as films on Algeria and��Apartheid��had been, the Mozambican documentaries offered prescriptions for transforming society and individuals.��Sylvia Hill, later a prominent anti-Apartheid��activist��in the��US, remembers leaving a screening of��A Luta Continua��and�����for the first time having this sense that you can have a science of change.��� The Dutch filmmaker Ike��Bertels��was so impressed by three female fighters in Margaret Dickinson���s film that she spent decades��following��their lives��for��the��bittersweet��documentary��Guerilla Grannies, in which she��finds ongoing��lessons for ���how to live in this world.�����With these films and their descendants finding expanded��audiences online,��a new generation��is��rediscovering��the social meaning of revolution and bonds of solidarity that��once fueled a global movement.

A final appeal from Ambassador Robert Van Lierop himself: As people rediscover these important films, it’s vital to remember the struggle continues to this day in Mozambique. The new state promised by FRELIMO faced glaring obstacles from its birth in 1975, including an extended civil war funded in part by the United States and major cyclones in the 1990s. The recent devastation caused by Cyclone Idai is another example of the ongoing inequality of the global system, this time exacerbated by the developed world’s inattention and inaction on climate change that disproportionately affects nations of the global South. We encourage readers to donate to relief efforts in Mozambique as the country continues to rebuild.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers