Beyond Binary

What does photography offer the trans feminism movement?

By Julia Bryan-Wilson

Andrea Bowers, Trans Liberation: Beauty in the Street (Johanna Saavedra), 2016

Courtesy the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York

She is striding down the middle of the empty street. She is striding down the street flanked by palm trees. She is striding down the street in a gray dress and strappy, red, open-toed shoes. She is striding down the street coming toward us. She is striding down the street holding a brick in one hand.

This large-scale, life-size photograph of Johanna Saavedra—a trans, Latina activist—is part of Andrea Bowers’s series Trans Liberation (2016), produced in collaboration with artist and organizer Ada Tinnell. Trans Liberation features three trans women activists of color—Saavedra, CeCe McDonald, and Jennicet Gutiérrez—photographed with weapons (brick, hammer, rifle) and in postures that nod to historical representations of revolutionary insurrection. Saavedra’s brick, for instance, references both a famed graphic from the student/worker uprisings of May 1968 in France and the brick thrown by African American trans pioneer Marsha P. Johnson at the 1969 Stonewall rebellion, which helped ignite the gay liberation movement in the United States. Even as the photographs confidently portray these women as stunning, beautiful, and strong, by some accounts they are not considered women at all—recently enacted bathroom laws mean their use of certain public ladies’ rooms is illegal, and they would not have been welcomed at the (now defunct) Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival with its “womyn-born-womyn”-only policy.

In another photograph, McDonald—who was convicted of manslaughter after defending herself in a racist, transphobic attack outside a bar in Minneapolis in 2011 and, despite entreaties by trans activists, served nineteen months in a men’s prison—is portrayed as an avenging angel of liberation in a flowing gown with wings spread out behind her and a sledgehammer tucked into her belt. Bowers, whose practice has long rotated around the imaging of social justice struggles, writes, “I wanted to document these activists because I believe they are some of the most powerful and courageous activists of this time. Over 70 percent of hate-motivated murders are against trans women, and 80 percent of those are trans women of color.” Gender might not be “real,” to cite theorists of social construction, but gender-based oppression certainly is.

Andrea Bowers, Trans Liberation: Building a Movement (Cece McDonald), 2016

Courtesy the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York

The photographs comprised only one component of Bowers’s multimedia exhibition, entitled Whose Feminism Is It Anyway?, at Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York, in spring 2016, but they were the show’s breakthrough centerpiece. The titular question is a direct quote from an influential essay by trans activist/writer Emi Koyama that discusses the racism that accompanies some trans-inclusion debates, as various camps stake their claims not only to who owns feminism, but who owns (and who is excluded from) the very definition of womanhood. The category of “woman” has never been singular or stable, and many—because of normative ideals about anatomy, about body size, about race, about age, about disability—have been barred from its rigid confines. Trans women of color continue to fight hard to change these conversations, fights allegorized in these portraits by the weapons wielded by Saavedra, McDonald, and Gutiérrez.

Bowers is perhaps most well known for her carefully wrought drawings (some of which were on display in Whose Feminism Is It Anyway?), but to document these figures as mythic heroines she turned decisively to photography, with its special capacities to depict not only the purported “real” but also to render visible “unreal” or fictive states of being. It is one of the first lessons to impart in any history of photography class: despite the vaunted truth value of a photograph, it is always the result of a partial, packaged, and framed viewpoint. The photograph’s alleged transparency is as mediated and produced as any other form of representation.

In a related vein, these photographs perform a denaturalizing function. Trans activism asks us to rethink the supposed truth of the binary gender system—one that sorts people at birth into two inviolable categories (boy or girl) and permits no crossing between them during a lifetime. In addition, sexist systems of inequality privilege men above women, as well as masculine above feminine; to counteract these strictures, trans feminism advocates for the flourishing of a range of genders and promotes solidarity between all kinds of women, including those who were born female and those who were not. Trans feminism also considers how gender intersects with race, class, ability, and age. It is thus worth asking: What does photography as an artistic resource, a visioning technology, and a tool of activist organizing have to offer the trans feminist movement? Current debates about the porousness and flexibility of gender identities hinge in part on questions of visibility and self-presentation—that is, how one looks, as well as how one looks back, is crucial. These are issues that photography is uniquely suited to address.

Julia Bryan-Wilson is Associate Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at the University of California, Berkeley.

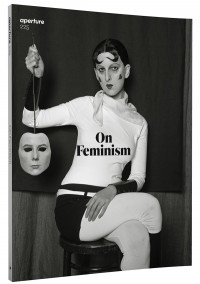

To continue reading this article, buy Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue. Aperture 225Aperture: The Magazine of Photography and Ideas

Aperture 225Aperture: The Magazine of Photography and Ideas

“On Feminism”

The winter issue of Aperture, “On Feminism,” arrives at a moment when the power and influence women hold on the world stage is irrefutable, and the very idea of gender is central to conversations about equality across the country, and around the globe. “On Feminism” focuses on intergenerational dialogues, debates, and strategies of feminism in photography and considers the immense contributions by artists whose work articulates or interrogates representations of women in media and society. Across more than one hundred years of photographs and images, “On Feminism” underscores how photography has shaped feminism as much as how feminism has shaped photography.

FRONT

Redux

Brian Wallis on Leonard Freed’s Black in White America, 1968

Spotlight

Eli Durst’s In Asmara by Alexandra Pechman

Curriculum

By Martha Rosler

Dispatches

Maria Nicolacopoulou on Athens

BACK

Object Lessons

Les Femmes de l’Avenir, 1900–1902

WORDS

On Feminism

Contributions by Catherine Morris, Zanele Muholi, Laurie Simmons, Johanna Fateman, Zackary Drucker, and A. L. Steiner

Modern Women: David Campany in Conversation with Marta Gili, Julie Jones, and Roxana Marcoci

The artists who redefined the course of twentieth-century photography

The Feminist Avant-Garde

In self-portraiture and body art, experimental pioneers of the 1970s

By Nancy Princenthal

Sex Wars Revisited

Lesbian erotica as critical rebellion

By Laura Guy

A Taste of Power: Renée Cox in Conversation with Uri McMillan

From Angela Davis to Beyoncé, the icons and avatars of black style

History Is Ours

The legacy of protest in video and performance

By Eva Díaz

On Defiance

How women have resisted representational photography

By Eva Respini

Beyond Binary

New visions of trans feminism

By Julia Bryan-Wilson

Our Bodies, Online

Feminist images in the age of Instagram

By Carmen Winant

PICTURES

Cosey Fanni Tutti

Introduction by Alison M. Gingeras

Gillian Wearing

Introduction by Jennifer Blessing

Yurie Nagashima

Introduction by Lesley A. Martin

Hannah Starkey

Introduction by Sara Knelman

Katharina Gaenssler

Introduction by Yvonne Bialek

Josephine Pryde

Introduction by Alex Klein

Laia Abril

Introduction by Karen Archey

Farah Al Qasimi

Introduction by Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

Martine Syms

Introduction by Amanda Hunt

Elle Pérez

Introduction by Salamishah Tillet

$24.95

The post Beyond Binary appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers