The making of Michael Jackson's Dangerous PART ONE

In January 1989, the Bad Tour ended with five concerts at the Memorial Sports Arena in Los Angeles. The tour grossed $125 million at the box office, of which Michael reportedly netted $40 million, making it the largest grossing tour in history. It also had the largest audience in history, with 4.4 million people attending the 123 shows.That January Michael's manager, Frank DiLeo, confirmed that his client would be retiring from touring in order to fulfil his movie dreams. “It’s time to pursue this in earnest,” DiLeo said. “We have stacks and stacks of scripts and proposals. We’ll sort through them and see what’s right for Michael.” But Michael’s older brother Marlon didn’t buy it. “I think he’s going to tour again,” he said. “I mean, you say something like that and then three or four years pass and you get the urge again.”After an exhausting 16 months on tour Michael spent some time at his new property, the Neverland Ranch, and evaluated theBadcampaign as a whole. The tour may have been a huge success, but Michael was disappointed with the commercial performance of theBadalbum. His target was 100 million sales, yet by early 1989Badhad ‘only’ sold one-fifth of that. The record label was ‘ecstatic’ whenBadshot past the 20 million mark, but Michael wasn’t –Thrillersold 15 million more copies in its first 18 months on sale.Frank DiLeo said everybody did ‘the best’ they could. “We made the best album and the best videos we could, we don’t have anything to be ashamed of,” he said in January 1989. But for Michael it wasn’t enough – a month later, DiLeo was out of a job. Somebody had to take the blame. It is estimated as many as 45 million copies ofBadhave been sold worldwide, placing it among the most successful of all time. But Michael wanted it to be the most successful. He also felt DiLeo had taken his wish to make his life ‘the greatest show on earth’ a little too far, with too many strange and false stories appearing in the press after 1985. As Michael was refusing to be interviewed during theBadera, much of his PR came through DiLeo. Michael’s hair/ make-up artist, Karen Faye, claims Michael fired DiLeo because he was stealing from him. Faye says John Branca provided proof to Michael that his own manager was stealing ticket revenue money from the Bad Tour.Read next:Author Mike Smallcombe discusses his book Making MichaelDiLeo himself claimed Michael was ‘talked into’ hiring another manager with a more established background in the movie industry, so he could fulfil his Hollywood dreams. By 1989, Michael was becoming more and more influenced by his business advisor, David Geffen. Michael looked up to Geffen, a hugely successful entertainment mogul, and listened to him carefully. At the end of the Bad Tour Michael also fired his accountant, Marshall Gelfrand, and replaced him with Richard Sherman, who worked for Geffen. DiLeo believed Michael’s decision to fire him wasn’t about the performance of theBadalbum (or the stealing of money, at least not publicly), but one instigated by his key advisors.In April 1989, the eighth and final video from theBadalbum, ‘Liberian Girl’, was filmed, although Michael only makes a very brief appearance at the end. The video was designed so Michael’s celebrity friends, including Steven Spielberg, John Travolta, and David Copperfield, were shown waiting on the set to get ready to film, only to discover that Michael was filming them all along. Michael’s short appearance shows him filming the set with a camera.

In January 1989, the Bad Tour ended with five concerts at the Memorial Sports Arena in Los Angeles. The tour grossed $125 million at the box office, of which Michael reportedly netted $40 million, making it the largest grossing tour in history. It also had the largest audience in history, with 4.4 million people attending the 123 shows.That January Michael's manager, Frank DiLeo, confirmed that his client would be retiring from touring in order to fulfil his movie dreams. “It’s time to pursue this in earnest,” DiLeo said. “We have stacks and stacks of scripts and proposals. We’ll sort through them and see what’s right for Michael.” But Michael’s older brother Marlon didn’t buy it. “I think he’s going to tour again,” he said. “I mean, you say something like that and then three or four years pass and you get the urge again.”After an exhausting 16 months on tour Michael spent some time at his new property, the Neverland Ranch, and evaluated theBadcampaign as a whole. The tour may have been a huge success, but Michael was disappointed with the commercial performance of theBadalbum. His target was 100 million sales, yet by early 1989Badhad ‘only’ sold one-fifth of that. The record label was ‘ecstatic’ whenBadshot past the 20 million mark, but Michael wasn’t –Thrillersold 15 million more copies in its first 18 months on sale.Frank DiLeo said everybody did ‘the best’ they could. “We made the best album and the best videos we could, we don’t have anything to be ashamed of,” he said in January 1989. But for Michael it wasn’t enough – a month later, DiLeo was out of a job. Somebody had to take the blame. It is estimated as many as 45 million copies ofBadhave been sold worldwide, placing it among the most successful of all time. But Michael wanted it to be the most successful. He also felt DiLeo had taken his wish to make his life ‘the greatest show on earth’ a little too far, with too many strange and false stories appearing in the press after 1985. As Michael was refusing to be interviewed during theBadera, much of his PR came through DiLeo. Michael’s hair/ make-up artist, Karen Faye, claims Michael fired DiLeo because he was stealing from him. Faye says John Branca provided proof to Michael that his own manager was stealing ticket revenue money from the Bad Tour.Read next:Author Mike Smallcombe discusses his book Making MichaelDiLeo himself claimed Michael was ‘talked into’ hiring another manager with a more established background in the movie industry, so he could fulfil his Hollywood dreams. By 1989, Michael was becoming more and more influenced by his business advisor, David Geffen. Michael looked up to Geffen, a hugely successful entertainment mogul, and listened to him carefully. At the end of the Bad Tour Michael also fired his accountant, Marshall Gelfrand, and replaced him with Richard Sherman, who worked for Geffen. DiLeo believed Michael’s decision to fire him wasn’t about the performance of theBadalbum (or the stealing of money, at least not publicly), but one instigated by his key advisors.In April 1989, the eighth and final video from theBadalbum, ‘Liberian Girl’, was filmed, although Michael only makes a very brief appearance at the end. The video was designed so Michael’s celebrity friends, including Steven Spielberg, John Travolta, and David Copperfield, were shown waiting on the set to get ready to film, only to discover that Michael was filming them all along. Michael’s short appearance shows him filming the set with a camera. Former Epic marketing chief Larry Stessel believes Michael only made a cameo appearance because he got tired of making videos by the end of theBadcampaign. “I was talking to Walter Yetnikoff about it and he said, ‘You gotta get him in the video’,” Stessel recalls. “So I called up Michael and I said, ‘You gotta be in this video someplace…’ He goes, ‘OK I have an idea’, and he goes, ‘You got one take, you got 15 minutes’.”When the single was released later that summer, it marked the end of theBadcampaign after two long years. Frank DiLeo estimates that betweenThriller,Bad, the tour and sponsorship deals, Michael earned as much as $350 million. Now the hugely successfulBadcampaign was over, it was time for Michael to ponder his next career move.For his next project, Michael made the decision to dispense with the services of Quincy Jones, even though the three albums the pair recorded together had sold over 70 million copies to date.One of the reasons Michael no longer wanted to work with Quincy was because he felt the producer was taking too much credit for his work. Walter Yetnikoff recalls Michael telling him he didn’t want Quincy to win any awards at the Grammys in 1984 for his role in producingThriller. “People will think he’s the one who did it, not me,” Michael told Yetnikoff. Quincy believes that key members of Michael’s entourage were whispering in his ear telling him that he had been getting too much credit.Quincy also felt Michael had lost faith in him and his knowledge of the market. “I remember when we were doingBadI had [Run] DMC in the studio because I could see what was coming with hip-hop,” he said. “And [Michael] was telling Frank DiLeo, ‘I think Quincy’s losing it and doesn’t understand the market anymore. He doesn’t know that rap is dead’.” Michael was also said to be unhappy after Quincy gave him a tough time over the inclusion of ‘Smooth Criminal’ onBad.Read next:Full interview with longtime Michael Jackson collaborator and friend Matt ForgerMost significantly, Michael wanted complete production freedom for his next project. OnBadMichael wasn’t always able to produce the way he wanted to, especially when it came to working with the Synclavier, because co-producer Quincy had his own methods. Future producer Brad Buxer said Michael wasn’t angry with his one-time mentor. “He has always had an admiration for him and an immense respect,” Buxer said. “But Michael wanted to control the creative process from A to Z. Simply put, he wanted to be his own boss. Michael was always very independent, and he also wanted to show that his success was not because of one man, namely Quincy.”MakingBadwas a stressful period for Michael; he was competing with himself in an attempt to make the album as successful asThriller. John Branca attempted to take some pressure off by persuading him to release a two-disc greatest hits collection (with up to five new songs included) to followBad, rather than an album of entirely new material.The collection was to be titledDecade 1979–1989and completed by August 1989, in preparation for a November release. In addition to the new songs, the original plan was to include four tracks fromOff the Wall(‘Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough’, ‘Rock With You’, ‘Off the Wall’ and ‘She’s Out of My Life’); seven fromThriller(‘Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’’, ‘The Girl Is Mine’, ‘Thriller’, ‘Beat It’, ‘Billie Jean’, ‘Human Nature’ and ‘P.Y.T.’) and six fromBad(‘Bad’, ‘The Way You Make Me Feel’, ‘I Just Can’t Stop Loving You’, ‘Man in the Mirror’, ‘Dirty Diana’ and ‘Smooth Criminal’). ‘Someone In The Dark’ (from the 1982E.T.storybook album), ‘State of Shock’ (the 1984 duet with Mick Jagger), The Jacksons song ‘This Place Hotel’, ‘Come Together’ (a Beatles cover recorded during theBadsessions) and adult versions of two Jackson 5 classics, ‘I’ll Be There’ and ‘Never Can Say Goodbye’, were also set to be included.

Former Epic marketing chief Larry Stessel believes Michael only made a cameo appearance because he got tired of making videos by the end of theBadcampaign. “I was talking to Walter Yetnikoff about it and he said, ‘You gotta get him in the video’,” Stessel recalls. “So I called up Michael and I said, ‘You gotta be in this video someplace…’ He goes, ‘OK I have an idea’, and he goes, ‘You got one take, you got 15 minutes’.”When the single was released later that summer, it marked the end of theBadcampaign after two long years. Frank DiLeo estimates that betweenThriller,Bad, the tour and sponsorship deals, Michael earned as much as $350 million. Now the hugely successfulBadcampaign was over, it was time for Michael to ponder his next career move.For his next project, Michael made the decision to dispense with the services of Quincy Jones, even though the three albums the pair recorded together had sold over 70 million copies to date.One of the reasons Michael no longer wanted to work with Quincy was because he felt the producer was taking too much credit for his work. Walter Yetnikoff recalls Michael telling him he didn’t want Quincy to win any awards at the Grammys in 1984 for his role in producingThriller. “People will think he’s the one who did it, not me,” Michael told Yetnikoff. Quincy believes that key members of Michael’s entourage were whispering in his ear telling him that he had been getting too much credit.Quincy also felt Michael had lost faith in him and his knowledge of the market. “I remember when we were doingBadI had [Run] DMC in the studio because I could see what was coming with hip-hop,” he said. “And [Michael] was telling Frank DiLeo, ‘I think Quincy’s losing it and doesn’t understand the market anymore. He doesn’t know that rap is dead’.” Michael was also said to be unhappy after Quincy gave him a tough time over the inclusion of ‘Smooth Criminal’ onBad.Read next:Full interview with longtime Michael Jackson collaborator and friend Matt ForgerMost significantly, Michael wanted complete production freedom for his next project. OnBadMichael wasn’t always able to produce the way he wanted to, especially when it came to working with the Synclavier, because co-producer Quincy had his own methods. Future producer Brad Buxer said Michael wasn’t angry with his one-time mentor. “He has always had an admiration for him and an immense respect,” Buxer said. “But Michael wanted to control the creative process from A to Z. Simply put, he wanted to be his own boss. Michael was always very independent, and he also wanted to show that his success was not because of one man, namely Quincy.”MakingBadwas a stressful period for Michael; he was competing with himself in an attempt to make the album as successful asThriller. John Branca attempted to take some pressure off by persuading him to release a two-disc greatest hits collection (with up to five new songs included) to followBad, rather than an album of entirely new material.The collection was to be titledDecade 1979–1989and completed by August 1989, in preparation for a November release. In addition to the new songs, the original plan was to include four tracks fromOff the Wall(‘Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough’, ‘Rock With You’, ‘Off the Wall’ and ‘She’s Out of My Life’); seven fromThriller(‘Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’’, ‘The Girl Is Mine’, ‘Thriller’, ‘Beat It’, ‘Billie Jean’, ‘Human Nature’ and ‘P.Y.T.’) and six fromBad(‘Bad’, ‘The Way You Make Me Feel’, ‘I Just Can’t Stop Loving You’, ‘Man in the Mirror’, ‘Dirty Diana’ and ‘Smooth Criminal’). ‘Someone In The Dark’ (from the 1982E.T.storybook album), ‘State of Shock’ (the 1984 duet with Mick Jagger), The Jacksons song ‘This Place Hotel’, ‘Come Together’ (a Beatles cover recorded during theBadsessions) and adult versions of two Jackson 5 classics, ‘I’ll Be There’ and ‘Never Can Say Goodbye’, were also set to be included. DecadeWith theDecadeformat in mind, Branca began renegotiating Michael’s contract with CBS Records. CBS was now under new ownership; the label was sold to the Japanese Sony Corporation for $2 billion in November 1987. The deal meant that artists contracted to CBS subsidiaries, in Michael’s case Epic Records, would see their music distributed by Sony. The company wouldn’t be renamed as Sony Music Entertainment until January 1991.In the summer of 1989, after a few months of rest at Neverland, Michael returned to the studio to begin recording new material forDecade. With the ranch over 100 miles away, Michael would mostly stay at his secret three-storey condominium in Century City – which he called the ‘Hideout’ – whenever he was working in Los Angeles.Now Quincy was out of the picture, Michael began working with Bill Bottrell and Matt Forger, just as he had done at the beginning of theBadsessions in 1985. Inspired by seeing the world, Michael had been writing songs while spending time at his ranch after the Bad Tour. Forger said Michael returned from his tour with certain impressions. “His social commentary kicked up a notch or two,” he said. “Most of the early songs we worked on were more socially conscious. His consciousness of the planet was much more to the forefront.” The most prominent of these were later titled ‘They Don’t Care About Us’ and ‘Earth Song’. Michael and Forger began working on these tracks in Westlake’s Studio C on Santa Monica Boulevard in June 1989.In addition to his engineering work, Forger was very much in charge of sound design. “Michael was getting me to get new sounds, all with different qualities, and there were some very unusual things,” Forger recalls. “One day, Michael said to me, ‘Hey Matt, my brother Tito collects old cars’. So we ended up using some of Tito’s old cars to make certain sounds. Michael loved metallic sounds, and sounds of nature. Another day, Michael had Billy [Bottrell] take a microphone to the back area of the studio, the loading area. They began smashing a metallic trashcan, and Michael had Billy record it. With Michael, you either had the sounds he wanted, or if not he would make you create those sounds. You never knew what sounds he would want.”While Forger was based at Westlake, Bottrell worked over at Ocean Way Recording, a short distance across Hollywood on Sunset Boulevard. Bottrell had recently finished working with Madonna on her albumLike a Prayer, mixing and also helping to produce the title track. During their sessions, Michael would hum melodies and grooves and then leave the studio while Bottrell developed these ideas with drum machines and samplers. But none of the ideas they worked on at Ocean Way would develop much further, and after a short period Bottrell joined Forger at Westlake, taking over Studio D while Forger remained in Studio C. The pair worked together in both rooms and also operated independently.In July 1989, Bottrell brought in keyboardist Brad Buxer to join the team. Buxer had been in Stevie Wonder’s band for three years at that point and also worked with Smokey Robinson and The Temptations. “The first thing I remember is seeing Michael right in front of me in the studio wearing a black hat and looking like the ultimate star,” Buxer recalls. “I had been working with a lot of celebrity artists by this time, but what really blew me away was this was the first time I was truly star struck. I had a huge smile on my face and so did he. We hit it off immediately. This first session was for drum and percussion programming. Michael’s favourite colour was red and in the studio there was a bright red Linn 9000 drum machine. If a mistake was made in the session while we were programming I would look at him and he would look at me, and we would both laugh. We instantly took to each other.” It was the beginning of a close personal and working relationship that would continue for another 20 years.HEAL THE WORLD WE LIVE INAs soon as Bottrell moved to Westlake, he and Buxer began working with Michael on a song called ‘Black or White’, which Michael wrote in early 1989 in his ‘Giving Tree’ overlooking the lake at Neverland. Climbing trees was always one of Michael’s favourite pastime activities and often sparked creativity. “My favourite thing is to climb trees, go all the way up to the top of a tree and I look down on the branches,” he explained. “Whenever I do that, it inspires me for music.”The first thing Michael did was hum the main riff of ‘Black or White’ to Bottrell, without specifying what instrument it would be played on. Bottrell then grabbed a Kramer American guitar and played to Michael’s singing. Michael also sang the rhythm before Bottrell put down a simple drum loop and added percussion.

DecadeWith theDecadeformat in mind, Branca began renegotiating Michael’s contract with CBS Records. CBS was now under new ownership; the label was sold to the Japanese Sony Corporation for $2 billion in November 1987. The deal meant that artists contracted to CBS subsidiaries, in Michael’s case Epic Records, would see their music distributed by Sony. The company wouldn’t be renamed as Sony Music Entertainment until January 1991.In the summer of 1989, after a few months of rest at Neverland, Michael returned to the studio to begin recording new material forDecade. With the ranch over 100 miles away, Michael would mostly stay at his secret three-storey condominium in Century City – which he called the ‘Hideout’ – whenever he was working in Los Angeles.Now Quincy was out of the picture, Michael began working with Bill Bottrell and Matt Forger, just as he had done at the beginning of theBadsessions in 1985. Inspired by seeing the world, Michael had been writing songs while spending time at his ranch after the Bad Tour. Forger said Michael returned from his tour with certain impressions. “His social commentary kicked up a notch or two,” he said. “Most of the early songs we worked on were more socially conscious. His consciousness of the planet was much more to the forefront.” The most prominent of these were later titled ‘They Don’t Care About Us’ and ‘Earth Song’. Michael and Forger began working on these tracks in Westlake’s Studio C on Santa Monica Boulevard in June 1989.In addition to his engineering work, Forger was very much in charge of sound design. “Michael was getting me to get new sounds, all with different qualities, and there were some very unusual things,” Forger recalls. “One day, Michael said to me, ‘Hey Matt, my brother Tito collects old cars’. So we ended up using some of Tito’s old cars to make certain sounds. Michael loved metallic sounds, and sounds of nature. Another day, Michael had Billy [Bottrell] take a microphone to the back area of the studio, the loading area. They began smashing a metallic trashcan, and Michael had Billy record it. With Michael, you either had the sounds he wanted, or if not he would make you create those sounds. You never knew what sounds he would want.”While Forger was based at Westlake, Bottrell worked over at Ocean Way Recording, a short distance across Hollywood on Sunset Boulevard. Bottrell had recently finished working with Madonna on her albumLike a Prayer, mixing and also helping to produce the title track. During their sessions, Michael would hum melodies and grooves and then leave the studio while Bottrell developed these ideas with drum machines and samplers. But none of the ideas they worked on at Ocean Way would develop much further, and after a short period Bottrell joined Forger at Westlake, taking over Studio D while Forger remained in Studio C. The pair worked together in both rooms and also operated independently.In July 1989, Bottrell brought in keyboardist Brad Buxer to join the team. Buxer had been in Stevie Wonder’s band for three years at that point and also worked with Smokey Robinson and The Temptations. “The first thing I remember is seeing Michael right in front of me in the studio wearing a black hat and looking like the ultimate star,” Buxer recalls. “I had been working with a lot of celebrity artists by this time, but what really blew me away was this was the first time I was truly star struck. I had a huge smile on my face and so did he. We hit it off immediately. This first session was for drum and percussion programming. Michael’s favourite colour was red and in the studio there was a bright red Linn 9000 drum machine. If a mistake was made in the session while we were programming I would look at him and he would look at me, and we would both laugh. We instantly took to each other.” It was the beginning of a close personal and working relationship that would continue for another 20 years.HEAL THE WORLD WE LIVE INAs soon as Bottrell moved to Westlake, he and Buxer began working with Michael on a song called ‘Black or White’, which Michael wrote in early 1989 in his ‘Giving Tree’ overlooking the lake at Neverland. Climbing trees was always one of Michael’s favourite pastime activities and often sparked creativity. “My favourite thing is to climb trees, go all the way up to the top of a tree and I look down on the branches,” he explained. “Whenever I do that, it inspires me for music.”The first thing Michael did was hum the main riff of ‘Black or White’ to Bottrell, without specifying what instrument it would be played on. Bottrell then grabbed a Kramer American guitar and played to Michael’s singing. Michael also sang the rhythm before Bottrell put down a simple drum loop and added percussion. Michael in his Giving Tree at NeverlandOnce Michael had filled out some lyrical ideas (the theme is about racial harmony) he performed a scratch vocal, as well as some background vocals. Bottrell loved them and strove to keep them as they were. “Of course, it had to please him or he would have never let me get away with that,” he said. Unusually for Michael, the scratch vocal remained untouched and ended up being used on the final version. The total length of the song at this stage was around a minute and a half, and there were still two big gaps in the middle to fill. Production of ‘Black or White’ would continue at other studios in Los Angeles later on.Bottrell was also asked to work on an idea Michael had previously started with Matt Forger, an environmental protest track which eventually became ‘Earth Song’. “I originally started that one with Michael, and then Bill continued working on it and developed it further, actually recording another version,” Forger said. “I don’t know if he used my version as a starting point or not. Sometimes Michael would work that way to get another person’s take on how they would interpret a song. But many of the elements were exactly the same as my version, so it seems he did at least hear it.”Read next:'Black or White' 25 years on: The story behind the song, video and THAT premiereMichael was on the Bad Tour in Vienna in June 1988 when he created the idea for ‘Earth Song in his hotel room. “It just suddenly dropped into my lap,” he recalled. “I was feeling so much pain and so much suffering of the plight of the Planet Earth. This [the song] is my chance to pretty much let people hear the voice of the planet.”Michael originally envisaged the song in the format of a trilogy, starting with an orchestral piece, then the main song and finishing with a spoken poem, which was later released as ‘Planet Earth’. He wanted a particularly powerful bassline, so Bottrell brought in Guy Pratt, a British bassist who was touring with Pink Floyd. “I basically stole the bassline from ‘Bad’ because I figured Michael would like it, but wouldn’t know why,” Pratt admitted. Andraé Crouch, who had previously worked on ‘Man in the Mirror’, brought in his choir to sing on the song’s epic finale. “They came in with the most wonderful arrangement,” Bottrell said.Bottrell remembers the very beginnings of another of his collaborations with Michael, a song which became the paranoid and despairing ‘Who Is It’. “‘Who Is It’ was Michael’s idea; he brought it to me, sang me parts and I produced them,” Bottrell recalls. “But I didn’t do as much arranging on this as the other songs.” Bottrell hired a soprano, Linda Harmon, to sing the main melody, which was recorded at his own studio in Pasadena, Los Angeles. ‘Monkey Business’ was another notable song the pair wrote together. “Michael talked like it [‘Monkey Business’] was purely fictional, a feeling, really, of poor southern country folk doing mischief to each other,” Bottrell explained.In the fall of 1989, Michael and his team began working on another environmental awareness anthem, ‘Heal the World’, which was originally called ‘Feed the World’. Michael was inspired to write ‘Earth Song’ and ‘Heal the World’ because he was concerned about the plight of the planet and global warming. “I knew it was coming, but I wish they [the songs] would have gotten people’s interest sooner,” he said. “That’s what I was trying to do with ‘Earth Song’, ‘Heal the World’, ‘We Are the World’, writing those songs to open up people’s consciousness. I wish people would listen to every word.” Famed primatologist Dr Jane Goodall said Michael was also inspired by the endangerment of chimpanzees. Goodall said Michael asked her for tapes of animals in distress because ‘he wanted to be angry and cry’ as he wrote.Michael created the lyrics and music for ‘Heal the World’ at the same time, which, like keeping his first ‘Black or White’ vocal, was another unusual way for him to work. “With ‘Heal the World’, it was just Michael and me at the piano and in that single two-hour session that song came into existence,” Brad Buxer said. “Billy [Bottrell] was in the control room recording the piano. Michael wrote the song and I executed it. The entire song was completed in that one session.”As part of his sound design work, Matt Forger was asked to help create the song’s intro. Michael wanted a spontaneous intro involving a child speaking about the state of the planet, so Forger went out to record ‘children just being children’. After recording over a hundred youngsters, Forger interviewed Ashley Farell, the daughter of his wife’s friend. “I just began asking her questions about planet earth without coaching her, and she said these lines so sincerely,” Forger recalls. “It was totally spontaneous and innocent, but after I started editing it to take out some of the hesitation and stammering, Michael said he wanted to leave it as it was. It was exactly what he wanted.”When Michael was once asked which three songs he would choose if he could only perform those for the rest of his life, ‘Heal the World’ made his list. “The point is that they’re [the three songs] very melodic and if they have a great important message that’s kinda immortal, that can relate to any time and space,” he explained.Keyboardist Michael Boddicker, who performed on ‘Heal the World’, believes the song says a lot about Michael. “It really represented his innocence when it came to his creations,” he said.After a few months of work at Westlake, producer/songwriter Bryan Loren, who was only 23 at the time, joined the team and worked in a third room at the studio. Michael liked Loren’s work in producing the 1987 Shanice albumDiscoveryand invited him to join the sessions.It was after songs such as ‘Black or White’ and ‘Heal the World’ were developed when Michael began entertaining the idea of recording a full album of new material, rather than a greatest hits package with only a handful of new songs. Michael was indecisive about theDecadeproject and unsure about which songs to include on it, and had already missed the August deadline for its completion. Yet no definite decision was made; Michael would keep creating and see how he felt later down the line.‘YOU WERE THERE’In early November Michael received a visit at the studio from a long-time friend, Buz Kohan, who was trying to persuade him to perform at an allstar tribute to Sammy Davis Jr’s 60 years in show business. Kohan was co-producing and writing the show, which was being taped for broadcast on November 13 at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. Kohan was joined on his studio visit by the show’s executive producer, George Schlatter.“George had promised the network four big stars to actually sell them the special and one of them was Michael,” Kohan said. “I don’t think we discussed what he would do that night we visited him at the studio, but Michael did commit to make every effort to appear and we would discuss what he was to do later. At the time, Michael was in extreme pain from the Pepsi commercial accident when his hair caught on fire.”Kohan and Schlatter hadn’t realised just how much distress Michael was in. “He took us into a back bathroom at the studio and asked us to feel his head,” Kohan recalls. “He told me he was in constant pain and on painkillers. Because of this, he truly didn’t know whether he would be able to perform at all.”Kohan went home and began thinking of the easiest, most gentle way of accommodating Michael’s needs and those of Sammy Davis and the show. “Suddenly this phrase popped into my head, ‘You Were There’,” Kohan said. “It applied so perfectly to Sammy and what he meant to so many young performers like Michael who were spared some of the pain and torment he went through to make things happen.”Michael Jackson performs 'You Were There' for Sammy Davis Jr:‘You Were There’ was originally just a poem, but could easily be turned into a lyric if music were added. Shortly after, Kohan wrote Michael a letter to tell him about the piece he had written. “I told Michael, ‘If the words strike a resonant chord in you; if they express how you feel about Sammy, and if you think you would like to spend an hour with me putting a melody to it before the show then give me a call’. And I said to him, ‘If you feel you just want to say the words without actually singing them I can arrange to have some lovely underscore under your voice’. Knowing how busy he was, I took it upon myself to write a tune to it and make a song out of it.”At around midnight the night before the show, Michael showed up at the Shrine Auditorium. Together with Kohan he went into the adjacent Shrine Exposition Hall, which was completely empty except for a grand piano and one light in the far corner. The producer, the arranger and a number of others involved in the show all stood outside – the arranger would have to do a chart by the next morning if Michael agreed to perform the song.“So Michael sat on the piano bench next to me,” Kohan said. “He used to call me ‘Buzzie Wuzzie’. I played the song for him on the grand piano, and Michael said, ‘Buzzie that’s beautiful’. We sat there for a while and made some adjustments to the melody line and changed a few words and chords, but Michael still wasn’t sure if he would be able to learn the song, agree to the arrangement, set his lighting and feel physically up to performing it. So I said to Michael, ‘This man, whether you are aware of it or not, has done so much for you, and if you pass up this last chance to say thank you, you will never forgive yourself ’.”Michael told Kohan he understood and that he would try, so at least the producers finally had a commitment of sorts. Everything then went into gear to prepare for the dress rehearsal, which by then was less than 12 hours away.“I knew Michael…he was such a perfectionist, he would spend days and weeks honing a performance or a song,” Kohan said. “But here he was, going on stage before an audience of millions to perform a song he had never sung before, which had an orchestration he would hear for the first time on the afternoon of the show. It was so out of character for him, but to his everlasting credit, he set the wheels in motion and went home with a piano track I made on a small cassette recorder to learn the song.”After rehearsing the song on the afternoon of the show, Michael went to his dressing room to rest and prepare. That evening he performed ‘You Were There’ for the first and only time, joining other stars such as Clint Eastwood, Mike Tyson, Whitney Houston, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Stevie Wonder in honouring Davis. Michael’s tribute brought tears to Davis, who was battling throat cancer. After Michael finished performing, he walked over to his idol and hugged him warmly. “Michael was brilliant, simple, eloquent and so powerful,” Kohan said. “The connection was made, the debt was paid, and it was one of the most memorable moments in a night that was overflowing with exceptional performances.”PROBLEMS, CHANGESBetween November 1989 and January 1990, Michael and the crew switched from Westlake to the Record One studio complex, located in Sherman Oaks in the San Fernando Valley. They had exclusive 24-hour access to the studio, costing an estimated $4,000 a day. Matt Forger said the move was made because of studio scheduling; at the time they required two studio rooms full time for a year, as Michael was entertaining the idea of recording a full album of new material rather than releasingDecade.Bruce Swedien, who had recently finished working on Quincy Jones’s albumBack on the Blockand was now available for Michael, joined the production at Record One along with engineer Brad Sundberg. Swedien, who engineeredOff the Wall,ThrillerandBad, was given a production role by Michael, alongside Bill Bottrell and Bryan Loren. Incidentally, Michael rejected the chance to contribute a song to Back on the Block. “I asked Michael to be on it,” Quincy said, “but he said he was afraid to do it because Walter Yetnikoff would be mad at him. But I think that if Michael had really wanted to be on the record, it would have been OK.”Shortly after moving to Record One, Michael received a visit at the studio from American Football star Bo Jackson. “I remember that day,” Matt Forger said. “I was working in the Studio B control room and Michael brought Bo in to meet us. He was impressive to meet in person, so muscular; you could feel his athletic prowess. After a few pleasant words we continued with our work. Just another day in the studio, you didn’t know what might happen or who might drop by. It was great fun.”

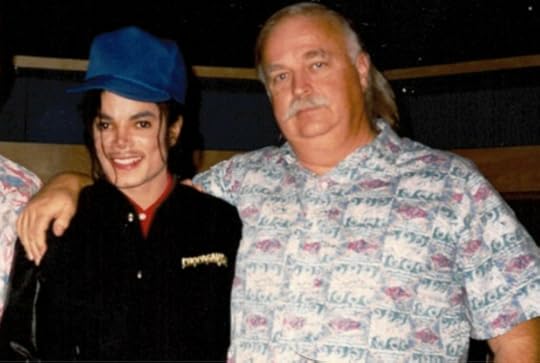

Michael in his Giving Tree at NeverlandOnce Michael had filled out some lyrical ideas (the theme is about racial harmony) he performed a scratch vocal, as well as some background vocals. Bottrell loved them and strove to keep them as they were. “Of course, it had to please him or he would have never let me get away with that,” he said. Unusually for Michael, the scratch vocal remained untouched and ended up being used on the final version. The total length of the song at this stage was around a minute and a half, and there were still two big gaps in the middle to fill. Production of ‘Black or White’ would continue at other studios in Los Angeles later on.Bottrell was also asked to work on an idea Michael had previously started with Matt Forger, an environmental protest track which eventually became ‘Earth Song’. “I originally started that one with Michael, and then Bill continued working on it and developed it further, actually recording another version,” Forger said. “I don’t know if he used my version as a starting point or not. Sometimes Michael would work that way to get another person’s take on how they would interpret a song. But many of the elements were exactly the same as my version, so it seems he did at least hear it.”Read next:'Black or White' 25 years on: The story behind the song, video and THAT premiereMichael was on the Bad Tour in Vienna in June 1988 when he created the idea for ‘Earth Song in his hotel room. “It just suddenly dropped into my lap,” he recalled. “I was feeling so much pain and so much suffering of the plight of the Planet Earth. This [the song] is my chance to pretty much let people hear the voice of the planet.”Michael originally envisaged the song in the format of a trilogy, starting with an orchestral piece, then the main song and finishing with a spoken poem, which was later released as ‘Planet Earth’. He wanted a particularly powerful bassline, so Bottrell brought in Guy Pratt, a British bassist who was touring with Pink Floyd. “I basically stole the bassline from ‘Bad’ because I figured Michael would like it, but wouldn’t know why,” Pratt admitted. Andraé Crouch, who had previously worked on ‘Man in the Mirror’, brought in his choir to sing on the song’s epic finale. “They came in with the most wonderful arrangement,” Bottrell said.Bottrell remembers the very beginnings of another of his collaborations with Michael, a song which became the paranoid and despairing ‘Who Is It’. “‘Who Is It’ was Michael’s idea; he brought it to me, sang me parts and I produced them,” Bottrell recalls. “But I didn’t do as much arranging on this as the other songs.” Bottrell hired a soprano, Linda Harmon, to sing the main melody, which was recorded at his own studio in Pasadena, Los Angeles. ‘Monkey Business’ was another notable song the pair wrote together. “Michael talked like it [‘Monkey Business’] was purely fictional, a feeling, really, of poor southern country folk doing mischief to each other,” Bottrell explained.In the fall of 1989, Michael and his team began working on another environmental awareness anthem, ‘Heal the World’, which was originally called ‘Feed the World’. Michael was inspired to write ‘Earth Song’ and ‘Heal the World’ because he was concerned about the plight of the planet and global warming. “I knew it was coming, but I wish they [the songs] would have gotten people’s interest sooner,” he said. “That’s what I was trying to do with ‘Earth Song’, ‘Heal the World’, ‘We Are the World’, writing those songs to open up people’s consciousness. I wish people would listen to every word.” Famed primatologist Dr Jane Goodall said Michael was also inspired by the endangerment of chimpanzees. Goodall said Michael asked her for tapes of animals in distress because ‘he wanted to be angry and cry’ as he wrote.Michael created the lyrics and music for ‘Heal the World’ at the same time, which, like keeping his first ‘Black or White’ vocal, was another unusual way for him to work. “With ‘Heal the World’, it was just Michael and me at the piano and in that single two-hour session that song came into existence,” Brad Buxer said. “Billy [Bottrell] was in the control room recording the piano. Michael wrote the song and I executed it. The entire song was completed in that one session.”As part of his sound design work, Matt Forger was asked to help create the song’s intro. Michael wanted a spontaneous intro involving a child speaking about the state of the planet, so Forger went out to record ‘children just being children’. After recording over a hundred youngsters, Forger interviewed Ashley Farell, the daughter of his wife’s friend. “I just began asking her questions about planet earth without coaching her, and she said these lines so sincerely,” Forger recalls. “It was totally spontaneous and innocent, but after I started editing it to take out some of the hesitation and stammering, Michael said he wanted to leave it as it was. It was exactly what he wanted.”When Michael was once asked which three songs he would choose if he could only perform those for the rest of his life, ‘Heal the World’ made his list. “The point is that they’re [the three songs] very melodic and if they have a great important message that’s kinda immortal, that can relate to any time and space,” he explained.Keyboardist Michael Boddicker, who performed on ‘Heal the World’, believes the song says a lot about Michael. “It really represented his innocence when it came to his creations,” he said.After a few months of work at Westlake, producer/songwriter Bryan Loren, who was only 23 at the time, joined the team and worked in a third room at the studio. Michael liked Loren’s work in producing the 1987 Shanice albumDiscoveryand invited him to join the sessions.It was after songs such as ‘Black or White’ and ‘Heal the World’ were developed when Michael began entertaining the idea of recording a full album of new material, rather than a greatest hits package with only a handful of new songs. Michael was indecisive about theDecadeproject and unsure about which songs to include on it, and had already missed the August deadline for its completion. Yet no definite decision was made; Michael would keep creating and see how he felt later down the line.‘YOU WERE THERE’In early November Michael received a visit at the studio from a long-time friend, Buz Kohan, who was trying to persuade him to perform at an allstar tribute to Sammy Davis Jr’s 60 years in show business. Kohan was co-producing and writing the show, which was being taped for broadcast on November 13 at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. Kohan was joined on his studio visit by the show’s executive producer, George Schlatter.“George had promised the network four big stars to actually sell them the special and one of them was Michael,” Kohan said. “I don’t think we discussed what he would do that night we visited him at the studio, but Michael did commit to make every effort to appear and we would discuss what he was to do later. At the time, Michael was in extreme pain from the Pepsi commercial accident when his hair caught on fire.”Kohan and Schlatter hadn’t realised just how much distress Michael was in. “He took us into a back bathroom at the studio and asked us to feel his head,” Kohan recalls. “He told me he was in constant pain and on painkillers. Because of this, he truly didn’t know whether he would be able to perform at all.”Kohan went home and began thinking of the easiest, most gentle way of accommodating Michael’s needs and those of Sammy Davis and the show. “Suddenly this phrase popped into my head, ‘You Were There’,” Kohan said. “It applied so perfectly to Sammy and what he meant to so many young performers like Michael who were spared some of the pain and torment he went through to make things happen.”Michael Jackson performs 'You Were There' for Sammy Davis Jr:‘You Were There’ was originally just a poem, but could easily be turned into a lyric if music were added. Shortly after, Kohan wrote Michael a letter to tell him about the piece he had written. “I told Michael, ‘If the words strike a resonant chord in you; if they express how you feel about Sammy, and if you think you would like to spend an hour with me putting a melody to it before the show then give me a call’. And I said to him, ‘If you feel you just want to say the words without actually singing them I can arrange to have some lovely underscore under your voice’. Knowing how busy he was, I took it upon myself to write a tune to it and make a song out of it.”At around midnight the night before the show, Michael showed up at the Shrine Auditorium. Together with Kohan he went into the adjacent Shrine Exposition Hall, which was completely empty except for a grand piano and one light in the far corner. The producer, the arranger and a number of others involved in the show all stood outside – the arranger would have to do a chart by the next morning if Michael agreed to perform the song.“So Michael sat on the piano bench next to me,” Kohan said. “He used to call me ‘Buzzie Wuzzie’. I played the song for him on the grand piano, and Michael said, ‘Buzzie that’s beautiful’. We sat there for a while and made some adjustments to the melody line and changed a few words and chords, but Michael still wasn’t sure if he would be able to learn the song, agree to the arrangement, set his lighting and feel physically up to performing it. So I said to Michael, ‘This man, whether you are aware of it or not, has done so much for you, and if you pass up this last chance to say thank you, you will never forgive yourself ’.”Michael told Kohan he understood and that he would try, so at least the producers finally had a commitment of sorts. Everything then went into gear to prepare for the dress rehearsal, which by then was less than 12 hours away.“I knew Michael…he was such a perfectionist, he would spend days and weeks honing a performance or a song,” Kohan said. “But here he was, going on stage before an audience of millions to perform a song he had never sung before, which had an orchestration he would hear for the first time on the afternoon of the show. It was so out of character for him, but to his everlasting credit, he set the wheels in motion and went home with a piano track I made on a small cassette recorder to learn the song.”After rehearsing the song on the afternoon of the show, Michael went to his dressing room to rest and prepare. That evening he performed ‘You Were There’ for the first and only time, joining other stars such as Clint Eastwood, Mike Tyson, Whitney Houston, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Stevie Wonder in honouring Davis. Michael’s tribute brought tears to Davis, who was battling throat cancer. After Michael finished performing, he walked over to his idol and hugged him warmly. “Michael was brilliant, simple, eloquent and so powerful,” Kohan said. “The connection was made, the debt was paid, and it was one of the most memorable moments in a night that was overflowing with exceptional performances.”PROBLEMS, CHANGESBetween November 1989 and January 1990, Michael and the crew switched from Westlake to the Record One studio complex, located in Sherman Oaks in the San Fernando Valley. They had exclusive 24-hour access to the studio, costing an estimated $4,000 a day. Matt Forger said the move was made because of studio scheduling; at the time they required two studio rooms full time for a year, as Michael was entertaining the idea of recording a full album of new material rather than releasingDecade.Bruce Swedien, who had recently finished working on Quincy Jones’s albumBack on the Blockand was now available for Michael, joined the production at Record One along with engineer Brad Sundberg. Swedien, who engineeredOff the Wall,ThrillerandBad, was given a production role by Michael, alongside Bill Bottrell and Bryan Loren. Incidentally, Michael rejected the chance to contribute a song to Back on the Block. “I asked Michael to be on it,” Quincy said, “but he said he was afraid to do it because Walter Yetnikoff would be mad at him. But I think that if Michael had really wanted to be on the record, it would have been OK.”Shortly after moving to Record One, Michael received a visit at the studio from American Football star Bo Jackson. “I remember that day,” Matt Forger said. “I was working in the Studio B control room and Michael brought Bo in to meet us. He was impressive to meet in person, so muscular; you could feel his athletic prowess. After a few pleasant words we continued with our work. Just another day in the studio, you didn’t know what might happen or who might drop by. It was great fun.” Michael and Bo Jackson at Record OneWorking at Record One at the time was a staff engineer called Rob Disner. “Michael didn’t say much to me at first, until one day he ran in screaming that there was a ‘vagabond’ sitting in the alley behind the studio,” Disner recalls. “I took a look, expecting Charlie Chaplin to pop out or something, but there was just some homeless guy sipping malt liquor out of a bag on the back steps.”Meanwhile, in late 1989 Michael’s earnings figures were released by Forbes magazine. It is estimated that theBadcampaign, as well the income from his music catalogues, saw Michael earn over $225 million between 1987 and 1989, a figure which made him the highest-paid entertainer of all time.As soon as the team moved to Record One and Bruce Swedien joined the production, many new song ideas were started. But by March 1990 Michael was still unsure about whether to go through with theDecadeproject – now due in the fall – or record a whole new album. “I’m not sure yet whether I’ll release a Greatest Hits album or a new album, it depends how I feel,” he told Adrian Grant, a journalist who visited him at the studio.Over the course of the first half of 1990 progress on Michael’s new project was very slow, with the uncertainty surrounding its format a major factor. Michael was also going through personal difficulties. In April a close friend of his, Ryan White, died from AIDS complications at the age of 18. His grandmother Martha Bridges also died a month later, as did one of his idols, Sammy Davis Jr. On June 3, Michael was admitted to St. John’s Hospital in Los Angeles with chest pains, which his publicist Bob Jones said were likely to have been brought on by his struggles. Tests later traced the pains to inflammation of rib cage cartilage. Although Michael was released from hospital five days later, the illness kept him out of the studio for several weeks. Michael was also unhappy with his CBS contract, which John Branca had been renegotiating for many months.By 1989 and 1990, Michael was becoming increasingly influenced by his close friend and business confidant, entertainment mogul David Geffen. After the Bad Tour he fired his accountant in favour of one who was working for Geffen, as well as his manager, Frank DiLeo. Michael finally hired a replacement for DiLeo in the summer of 1990. The new man, Sandy Gallin, who was brought in along with his management partner Jim Morey, was also a Geffen associate.Gallin recalls the first time he spoke to Michael at Record One. “John Branca called me and took me to the studio, and we clicked right away,” Gallin said. “We had conversations about his music, and where he could go with selling records and touring. That night, we got talking about how big a star he could become, and he felt we were on the same wavelength. Michael knew how to seduce people better than anybody, and he just told me how much he liked me, and that I made him feel good in the meeting.” Michael played some of his new music to Gallin, who was blown away. “It was unbelievable, spectacular, and I got really turned on. He really was, at that time, at the top of his game.”One thing the pair didn’t discuss was movies. “Our conversation was much more about Michael continuing to be the biggest record seller in the world,” Gallin said. “In his mind, he might have thought, ‘Sandy has produced many television shows and he’ll be able to get me into the movie business’. But we didn’t actually discuss that until later on.” Yet DiLeo believed it was the ‘promise’ of a movie career under Gallin’s stewardship that led to his own dismissal.

Michael and Bo Jackson at Record OneWorking at Record One at the time was a staff engineer called Rob Disner. “Michael didn’t say much to me at first, until one day he ran in screaming that there was a ‘vagabond’ sitting in the alley behind the studio,” Disner recalls. “I took a look, expecting Charlie Chaplin to pop out or something, but there was just some homeless guy sipping malt liquor out of a bag on the back steps.”Meanwhile, in late 1989 Michael’s earnings figures were released by Forbes magazine. It is estimated that theBadcampaign, as well the income from his music catalogues, saw Michael earn over $225 million between 1987 and 1989, a figure which made him the highest-paid entertainer of all time.As soon as the team moved to Record One and Bruce Swedien joined the production, many new song ideas were started. But by March 1990 Michael was still unsure about whether to go through with theDecadeproject – now due in the fall – or record a whole new album. “I’m not sure yet whether I’ll release a Greatest Hits album or a new album, it depends how I feel,” he told Adrian Grant, a journalist who visited him at the studio.Over the course of the first half of 1990 progress on Michael’s new project was very slow, with the uncertainty surrounding its format a major factor. Michael was also going through personal difficulties. In April a close friend of his, Ryan White, died from AIDS complications at the age of 18. His grandmother Martha Bridges also died a month later, as did one of his idols, Sammy Davis Jr. On June 3, Michael was admitted to St. John’s Hospital in Los Angeles with chest pains, which his publicist Bob Jones said were likely to have been brought on by his struggles. Tests later traced the pains to inflammation of rib cage cartilage. Although Michael was released from hospital five days later, the illness kept him out of the studio for several weeks. Michael was also unhappy with his CBS contract, which John Branca had been renegotiating for many months.By 1989 and 1990, Michael was becoming increasingly influenced by his close friend and business confidant, entertainment mogul David Geffen. After the Bad Tour he fired his accountant in favour of one who was working for Geffen, as well as his manager, Frank DiLeo. Michael finally hired a replacement for DiLeo in the summer of 1990. The new man, Sandy Gallin, who was brought in along with his management partner Jim Morey, was also a Geffen associate.Gallin recalls the first time he spoke to Michael at Record One. “John Branca called me and took me to the studio, and we clicked right away,” Gallin said. “We had conversations about his music, and where he could go with selling records and touring. That night, we got talking about how big a star he could become, and he felt we were on the same wavelength. Michael knew how to seduce people better than anybody, and he just told me how much he liked me, and that I made him feel good in the meeting.” Michael played some of his new music to Gallin, who was blown away. “It was unbelievable, spectacular, and I got really turned on. He really was, at that time, at the top of his game.”One thing the pair didn’t discuss was movies. “Our conversation was much more about Michael continuing to be the biggest record seller in the world,” Gallin said. “In his mind, he might have thought, ‘Sandy has produced many television shows and he’ll be able to get me into the movie business’. But we didn’t actually discuss that until later on.” Yet DiLeo believed it was the ‘promise’ of a movie career under Gallin’s stewardship that led to his own dismissal. Michael, Sandy Gallin and MadonnaAdvising Michael to replace DiLeo with Gallin was said to be part of Geffen’s wider agenda of avenging his enemy Walter Yetnikoff, the CBS president. The two were formerly close friends, but their relationship soured at the tail end of the eighties. They often fell out as Geffen headed his own rival record label, Geffen Records, but Yetnikoff started to take matters to another level.“He was pissed at me for a couple of reasons,” Yetnikoff explained. “At Michael Jackson’s whining insistence, I told Geffen he couldn’t use a Michael track [the unreleased ‘Come Together’ from theBadsessions] for theDays of Thundersoundtrack; and I kept circulating the story that I wanted David [who is openly gay] to show my girlfriend how to give superior blow jobs. In short, I showed him contempt at every turn.” Another bad move by Yetnikoff was making enemies of Geffen’s powerful attorney, Allen Grubman. Yetnikoff said he treated Grubman, who also represented many CBS artists, “like a schlemiel”.Yetnikoff said an infuriated Geffen then went on a ‘power tear’ after selling his label to MCA Records in March 1990 for $550 million (although he would carry on running it until 1995). One way of wreaking havoc for Yetnikoff would be to turn his most prized asset, Michael Jackson, against him by making Michael want to leave the label, which would alarm its new Japanese executives. Although Michael always had a good relationship with Yetnikoff, he listened to Geffen carefully because he looked to him like a father and admired him as a hugely successful business magnate.Geffen discussed with Michael his relationship with CBS, convincing him that the label was making more money on his albums and videos than he was making himself. Geffen said one of the reasons he didn’t have the best recording contract possible was because John Branca had a close relationship with Yetnikoff, much like Frank DiLeo did. “Rightly or wrongly, Michael was apparently unhappy – or at least concerned – with the way Branca was handling the renegotiation,” a ‘top level executive’ told theLos Angeles Times. “He seemed to feel he needed someone who wasn’t so closely associated with CBS as Branca.” Michael was also beginning to grow anxious over Branca’s representation of other artists, such as The Rolling Stones.Geffen’s supposed plan worked, as Michael was so annoyed that he began to think about leaving CBS altogether, with Geffen/MCA Records a possible destination. But Michael was unable to simply walk away because he still legally owed CBS four more albums, and the label would be able to sue for damages if he reneged on his contract.Michael told CBS he wouldn’t be delivering his new album until his contract was improved, and felt the solution was to fire Branca and hire a new attorney to secure a better deal. Convinced it was the right decision, Michael dismissed Branca in the summer of 1990 after ten hugely successful years of working together. Much to Yetnikoff’s dismay, Michael replaced him with a three man team including Bert Fields for litigation, and for negotiating his new record deal…Allen Grubman.Grubman began putting together a contract which Yetnikoff considered to be ‘outrageous’, but Michael refused to deliver his album until the label agreed to it. Word got back to the Japanese executives that Michael was unhappy, with Yetnikoff the reason. For Yetnikoff, the writing was on the wall. Michael had transferred his loyalty to Geffen, and with Yetnikoff’s relationship with other CBS artists – including Bruce Springsteen – also souring, his position as CBS president looked extremely vulnerable. Having lost the support of his key artists, and with his eccentric behaviour also worrying the executives, Yetnikoff was fired in September 1990 after 15 years in charge. He was replaced by his understudy, Tommy Mottola.Yetnikoff believes it was Geffen who influenced Michael to fire DiLeo and Branca, two of Yetnikoff’s close allies, and replace them with his own associates, in an attempt to turn Michael against him. One of Michael’s new attorneys, Bert Fields, admits it was Geffen who brought him and Michael together. Perhaps tellingly, Branca’s law partner Kenneth Ziffren also severed his ties with Geffen and his company in the wake of Branca’s dismissal. Geffen, however, said Michael made the decisions with his own best interests at heart. “Michael changed lawyers because he wanted to,” he said. “He felt John Branca was too close to Walter.” He also denied being behind a coup to get Yetnikoff fired. “People want to make me out as having more to do with all of this than I had,” Geffen said. “He shot himself in the head. None of us had anything to do with it.”NEW ALBUM, NEW SONGSIn the summer of 1990, Michael finally decided to shelve theDecadeproject in favour of an album of new material, due to an avalanche of song ideas. “Michael simply wasn’t interested in old material, he wanted to keep creating,” Matt Forger said. “We just had too many new ideas.” David Geffen was also said to have influenced the decision. The album was pencilled in for a January 1991 release.Once he recovered from his illness, Michael resumed work in the studio. After starting work on ‘Black or White’, ‘Earth Song’, ‘Who Is It’ and ‘Monkey Business’ at Westlake, Michael and Bill Bottrell developed more song ideas at Record One. Bottrell offered Michael something the other producers didn’t. “I was the influence that he [Michael] otherwise didn’t have,” Bottrell said. “I was the rock guy and also the country guy, which nobody else was.”

Michael, Sandy Gallin and MadonnaAdvising Michael to replace DiLeo with Gallin was said to be part of Geffen’s wider agenda of avenging his enemy Walter Yetnikoff, the CBS president. The two were formerly close friends, but their relationship soured at the tail end of the eighties. They often fell out as Geffen headed his own rival record label, Geffen Records, but Yetnikoff started to take matters to another level.“He was pissed at me for a couple of reasons,” Yetnikoff explained. “At Michael Jackson’s whining insistence, I told Geffen he couldn’t use a Michael track [the unreleased ‘Come Together’ from theBadsessions] for theDays of Thundersoundtrack; and I kept circulating the story that I wanted David [who is openly gay] to show my girlfriend how to give superior blow jobs. In short, I showed him contempt at every turn.” Another bad move by Yetnikoff was making enemies of Geffen’s powerful attorney, Allen Grubman. Yetnikoff said he treated Grubman, who also represented many CBS artists, “like a schlemiel”.Yetnikoff said an infuriated Geffen then went on a ‘power tear’ after selling his label to MCA Records in March 1990 for $550 million (although he would carry on running it until 1995). One way of wreaking havoc for Yetnikoff would be to turn his most prized asset, Michael Jackson, against him by making Michael want to leave the label, which would alarm its new Japanese executives. Although Michael always had a good relationship with Yetnikoff, he listened to Geffen carefully because he looked to him like a father and admired him as a hugely successful business magnate.Geffen discussed with Michael his relationship with CBS, convincing him that the label was making more money on his albums and videos than he was making himself. Geffen said one of the reasons he didn’t have the best recording contract possible was because John Branca had a close relationship with Yetnikoff, much like Frank DiLeo did. “Rightly or wrongly, Michael was apparently unhappy – or at least concerned – with the way Branca was handling the renegotiation,” a ‘top level executive’ told theLos Angeles Times. “He seemed to feel he needed someone who wasn’t so closely associated with CBS as Branca.” Michael was also beginning to grow anxious over Branca’s representation of other artists, such as The Rolling Stones.Geffen’s supposed plan worked, as Michael was so annoyed that he began to think about leaving CBS altogether, with Geffen/MCA Records a possible destination. But Michael was unable to simply walk away because he still legally owed CBS four more albums, and the label would be able to sue for damages if he reneged on his contract.Michael told CBS he wouldn’t be delivering his new album until his contract was improved, and felt the solution was to fire Branca and hire a new attorney to secure a better deal. Convinced it was the right decision, Michael dismissed Branca in the summer of 1990 after ten hugely successful years of working together. Much to Yetnikoff’s dismay, Michael replaced him with a three man team including Bert Fields for litigation, and for negotiating his new record deal…Allen Grubman.Grubman began putting together a contract which Yetnikoff considered to be ‘outrageous’, but Michael refused to deliver his album until the label agreed to it. Word got back to the Japanese executives that Michael was unhappy, with Yetnikoff the reason. For Yetnikoff, the writing was on the wall. Michael had transferred his loyalty to Geffen, and with Yetnikoff’s relationship with other CBS artists – including Bruce Springsteen – also souring, his position as CBS president looked extremely vulnerable. Having lost the support of his key artists, and with his eccentric behaviour also worrying the executives, Yetnikoff was fired in September 1990 after 15 years in charge. He was replaced by his understudy, Tommy Mottola.Yetnikoff believes it was Geffen who influenced Michael to fire DiLeo and Branca, two of Yetnikoff’s close allies, and replace them with his own associates, in an attempt to turn Michael against him. One of Michael’s new attorneys, Bert Fields, admits it was Geffen who brought him and Michael together. Perhaps tellingly, Branca’s law partner Kenneth Ziffren also severed his ties with Geffen and his company in the wake of Branca’s dismissal. Geffen, however, said Michael made the decisions with his own best interests at heart. “Michael changed lawyers because he wanted to,” he said. “He felt John Branca was too close to Walter.” He also denied being behind a coup to get Yetnikoff fired. “People want to make me out as having more to do with all of this than I had,” Geffen said. “He shot himself in the head. None of us had anything to do with it.”NEW ALBUM, NEW SONGSIn the summer of 1990, Michael finally decided to shelve theDecadeproject in favour of an album of new material, due to an avalanche of song ideas. “Michael simply wasn’t interested in old material, he wanted to keep creating,” Matt Forger said. “We just had too many new ideas.” David Geffen was also said to have influenced the decision. The album was pencilled in for a January 1991 release.Once he recovered from his illness, Michael resumed work in the studio. After starting work on ‘Black or White’, ‘Earth Song’, ‘Who Is It’ and ‘Monkey Business’ at Westlake, Michael and Bill Bottrell developed more song ideas at Record One. Bottrell offered Michael something the other producers didn’t. “I was the influence that he [Michael] otherwise didn’t have,” Bottrell said. “I was the rock guy and also the country guy, which nobody else was.” Michael in his lounge at Record One studioWith ‘Beat It’ and ‘Dirty Diana’ featuring on the last two albums, Michael wanted to write another song with ‘a rock edge to it’. The idea for ‘Give In to Me’, a hard rock ballad, came when Bottrell played a tune on his guitar in the studio one day. Michael loved what he was hearing and added a melody, before the two performed a live take together with Bottrell on guitar and Michael singing.Michael added lyrics, and Guns ’N’ Roses guitarist Slash was invited to perform on the song as a special guest. “He [Michael] sent me a tape of the song that had no guitars other than some of the slow picking,” Slash recalls. “I called him and sang over the phone what I wanted to do. I basically went in [to the studio] and started to play it – that was it. It was really spontaneous in that way. Michael just wanted whatever was in my style. He just wanted me to do that. No pressure. He was really in sync with me.”‘Give In to Me’ was originally drafted as a dance track rather than hard rock, with a drum beat programmed to play while Michael sang and Bottrell played the electric guitar. The song evolved and ended up as a rock track, but Bottrell regrets changing it from its original concept. “We took that song too far,” he said. “It was me who got insecure and started layering things. Eventually, he [Michael] had Slash come in and add loads of guitars, and the song was transformed; not for the better, in my view. And that had nothing to do with Slash, but by virtue of the production that went into it.”It was at Record One where Michael and Bottrell also filled in the two large gaps that still existed in the middle of ‘Black or White’. Michael had the idea for a heavy guitar section, and Bottrell suggested they insert a rap.Michael sang the riff to the heavy guitar section to Bottrell, who then hired his friend Tim Pierce, as he couldn’t play that kind of guitar. “Tim laid down some beautiful tracks with a Les Paul and a big Marshall, playing the chords that Michael had hummed to me – that’s a pretty unusual approach,” Bottrell said. “People will hire a guitar player and say ‘Well, here’s the chord. I want it to sound kinda like this’, and the guitarist will have to come up with the part. However, Michael hums every rhythm and note or chord, and he can do that so well. He describes the sound that the record will have by singing it to you… and we’re talking about heavy metal guitars here!”Pierce recorded his parts for ‘Black or White’ at Record One in one day, and also played on ‘Give In to Me’. “Firstly we did the bridge for ‘Black or White’, and Michael was present for that,” Pierce recalls. “He wanted a heavy metal guitar part and that’s what I brought in. After we finished that part, I then did my part on ‘Give In to Me’. It was just Bill and me… Michael had gone by then. Michael was really sweet, nice, and looked me in the eye whenever we spoke. I liked that. He looked good as well, like a real superstar. He was definitely a fourteen-year-old wrapped in a thirtyyear-old body.”The rap for ‘Black or White’ was now the only section left to record. “All the time I kept telling Michael that we had to have a rap, and he brought in rappers like LL Cool J who were performing on other songs,” Bottrell said. “Somehow, I didn’t have access to them for ‘Black or White’, and it was getting later and later and I wanted the song to be done. So, one day I wrote the rap – I woke up in the morning and, before my first cup of coffee, I began writing down what I was hearing, because the song had been in my head for about eight months by that time and it was an obsession to try and fill that last gap.”Although Bottrell wasn’t a fan of white rap, he performed it himself and played it for Michael the next day. “He went ‘Ohhh, I love it Bill, I love it. That should be the one’. I kept saying ‘No, we’ve got to get a real rapper’, but as soon as he heard my performance he was committed to it and wouldn’t consider using anybody else. I was OK with it. I couldn’t really tell if it sounded good, but after the record came out I did get the impression that people accepted it as a viable rap.” In the credits, the rapper is named LTB. “LTB stood for ‘MC Leave It to Beaver’, an obvious reference to my cultural heritage,” Bottrell explained. “Lesson learned – never joke around with credits.”Matt Forger helped to design the ‘Black or White’ intro, with Slash playing guitar and Bottrell playing the dad. A young actor named Andres McKenzie was brought in to play the son. Many believed it was the voice ofHome Alonestar Macaulay Culkin, although he wasn’t involved until the video shoot.Michael wasn’t present for the recording session, much to Slash’s disappointment. Bottrell himself was frustrated that the credits portrayed Slash as playing the main guitar section throughout the song. Slash only played the ‘intro’ section, whereas Bottrell played the whole song. “I was frustrated by the printed credits on the album for ‘Black or White’,” Bottrell admitted. “Because of the way it worked grammatically, most people thought Slash played guitar on the song. Bad luck for my legacy.”By the fall of 1990, Michael had also come up with an idea for the music track Bottrell originally crafted from ‘Streetwalker’ two years earlier. The track Bottrell made had no title, melody or lyrics, but Michael listened to it many times, and one day a melody came to him.The song, about a predatory lover, would be called ‘Dangerous’. Seconds before Michael was about to record vocals for a demo in the studio, he attempted to move a makeshift recording booth wall behind him, but the legs became unstable and the wall fell straight on his head. “All the lights were off, and right before I started singing – I think it was seven feet tall – this huge wall fell on my head, and it made a loud banging sound,” Michael recalled. “It hurt, but I didn’t realise how much it hurt me till the next day, and I was kinda dizzy. But it’s pretty much on tape, if you played the demo of us working on ‘Dangerous’, it was even recorded.”After the incident, Michael continued to record for over an hour. When the session finished engineer Brad Sundberg called a doctor, who advised him Michael should be assessed for concussion, so Sundberg took him to hospital.Although Bottrell would continue to tweak the song over the coming months, Michael still wasn’t fully satisfied with it.Over the course of 1990, Michael also worked with Bruce Swedien on a number of new songs. The majority of these were written by Michael and co-produced by Swedien. The pair brought in former ‘A-Team’ musicians Michael Boddicker, David Paich, Steve Porcaro, Greg Phillinganes, Paulinho Da Costa and Jerry Hey to play on the tracks, and newcomer Brad Buxer also contributed heavily.