How to Live in a Dying Town

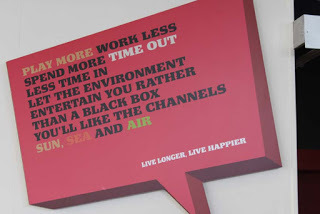

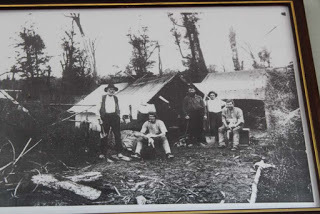

The message that greets you in the Robert Harris coffee shop in GreymouthGreymouth, at the mouth of the Grey River, on the West Coast at the other end of the Trans-Alpine railroad, is a town most people drive through to get to somewhere else. But it wasn't always like that. Once it was the Gold Rush destination of New Zealand. In 1864 men were flocking to what was then known as the Greenstone Creek in search of the shiny metal, camping out and living rough, hoping to get rich.

The message that greets you in the Robert Harris coffee shop in GreymouthGreymouth, at the mouth of the Grey River, on the West Coast at the other end of the Trans-Alpine railroad, is a town most people drive through to get to somewhere else. But it wasn't always like that. Once it was the Gold Rush destination of New Zealand. In 1864 men were flocking to what was then known as the Greenstone Creek in search of the shiny metal, camping out and living rough, hoping to get rich.

Timber was a big business too. On the West Coast there was an impenetrable rainforest just waiting to be logged out. And they did, using horses to pull the big trees out of the forest.

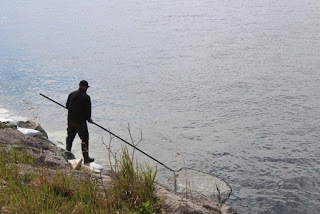

But that was nothing to what happened when the miners discovered coal - the black variety was more profitable than the much rarer glittery stuff. After the coal mining began, a railway was needed to connect up the mines, and a shipping port to ship it out. All that is left of the wharves today are the cranes - made in my home-town Carlisle in the UK! - and the odd bloke fishing for whitebait.

Cranes made in Carlisle, Cumbria - a long way from home!

Cranes made in Carlisle, Cumbria - a long way from home! Dipping for WhitebaitThe Grey River has a sandbar at the entrance that claimed dozens of ships. The slightest mistake, the smallest change in the weather or the tide and ships ran aground. It was one of the most difficult ports in New Zealand, much disliked by the Captains and pilots.

Dipping for WhitebaitThe Grey River has a sandbar at the entrance that claimed dozens of ships. The slightest mistake, the smallest change in the weather or the tide and ships ran aground. It was one of the most difficult ports in New Zealand, much disliked by the Captains and pilots. Shipwreck on the Greymouth Bar. Photo NZ Gov encyclopaediaEven the Harbour Board offices are closed now - the beautiful art deco building considered an earthquake risk until the money can be found to strengthen it.

Shipwreck on the Greymouth Bar. Photo NZ Gov encyclopaediaEven the Harbour Board offices are closed now - the beautiful art deco building considered an earthquake risk until the money can be found to strengthen it.

A lot of the coal was shipped out across the Alps, through Arthur's Pass, by rail to the east coast port of Lyttleton, which was safer and easier. The port at Greymouth slowly died. The town became dependent on coal. But the seams were as dangerous as the port - producing a lot of methane and other gases. The mines were fraught with accidents. Most recently, the notorious Pike River disaster, where a series of explosions and fires rocked the mine killing everyone underground at the time. 29 men died in the tragedy and some bodies have never been recovered because it is too dangerous to go down.

Pike River Mine - the aftermathTwelve years ago around 800 men worked in the mining industry. Today only two mines remain open and employ only 40 men. Even the club, named The Coal Face, is closed.

Pike River Mine - the aftermathTwelve years ago around 800 men worked in the mining industry. Today only two mines remain open and employ only 40 men. Even the club, named The Coal Face, is closed.

Greymouth feels like a town that has lost its way. But it still has a great deal going for it. The situation on the west coast is utterly beautiful and there are wonderful art deco buildings lining the streets. There are several big, old colonial hotels and it would be a good base to tour the area.

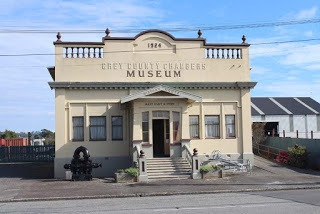

The Museum is an architectural gem - it has the feel of one of those fascinating antique shops that allow you to trawl through the bric-a-brac. There are rooms full of photographs and bits of wrecked ships, personal effects, and mining equipment.

I loved the old Greymouth switchboard.

And the diving suit and boots, dating from the early days of the port when divers in lead boots were winched down to salvage the wrecks.

I had a comfortable hotel and evening meal and thoroughly enjoyed my walk back in time through Greymouth's history. A story summed up by the old Bank of New Zealand building (Katherine Mansfield's father was a director of the bank) which is now an art gallery with the lettering on the front blanked out to create a new message. This is A New Land.

Bank of New Zealand - A New Land

Bank of New Zealand - A New LandNow I'm heading out again, over the pass and down to the far south - the windy, wild reaches of the Catlins, looking out towards Antarctica.

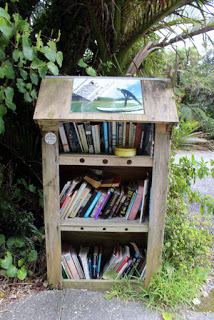

Favourite thing? This roadside bookshop with an honesty box on the shelf!

Published on September 27, 2016 22:03

No comments have been added yet.