The Engines of War: How the B&O Railroad helped save the Union

From Baltimore’s Pratt Street Riot in April 1861 that saw the first fatality of the Civil War to President Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train in 1865, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was a rolling witness to history.

From Baltimore’s Pratt Street Riot in April 1861 that saw the first fatality of the Civil War to President Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train in 1865, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was a rolling witness to history.

“You could argue that it was the most crucial railroad in the United States during the war because it ran across the dividing line between the North and South,” says Courtney Wilson, executive director of the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore.

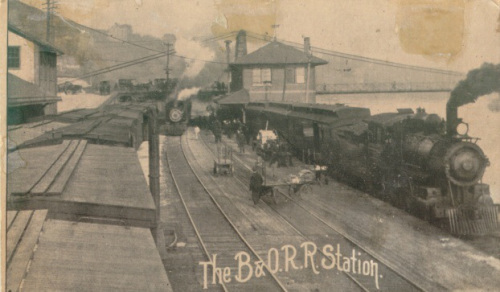

At the beginning of the war, the B&O had 513 miles of track that ran from Washington, DC, to Wheeling, Virginia.

“From Wheeling, the train would be taken across the river on floats to Parkersburg,” Wilson notes. From there, connections could be made to other railroads, but the Washington, DC, connection was the critical one. In terms of rail service, the B&O was Washington’s lifeline to the Union.

Despite being in the Union, the rail line ran through states with Southern sympathies or states that were actually in the Confederate States of America. This made it a target too tempting to ignore. Over the course of the war, 143 raids and battles would involve the B&O.

New Tactics

In terms of tactics and strategy, the Civil War was unlike any conflict fought before, largely because of the use of railroads.

Most of the nation’s 200 railroads at the start of the war remained loyal to the Union. Among these railroads, the majority used a uniform distance between their rails. This allowed the Union to move troops and goods faster and with fewer transfers.

This was a significant tactical advantage for the North. The trick was for Union generals to learn to make use of it.

“I would say that they adapted to it very quickly, particularly that they could move troops six times the distance in a 24-hour period,” says Wilson.

“A Southern Railroad”

Marylander John W. Garrett (for whom Garrett County is named) was president of the B&O during the Civil War years. Garrett had been born in Virginia and still loved the Old Dominion, though it was considered an enemy of the state where he lived as an adult.

“His loyalties were in question at first because he had called the B&O a Southern railroad,” Wilson says. He also referred to Confederate leaders as “our Southern friends.”

However, the Confederacy also had doubts about Garrett’s loyalty to the Southern cause. After the Pratt Street Riot, a group of Southern sympathizers threatened to “destroy every bridge and tear up your track” along the railroad.

“It was two to three months before he won the confidence of the president,” Wilson says, and that came about because Garrett, as well as many Maryland businessmen with pro-Southern leanings, realized that their commercial interests lay with the Union.

John Stover wrote in History of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, “John W. Garrett might claim that the B&O was a Southern line, but in his heart he knew that both the prosperity and the future of his railroad lay with the North, the West, and the Union, rather than the South.”

Once Garrett came to this realization, he committed himself to the Union cause and didn’t waver.

Pre-War Engagements

Even before the Civil War started with the bombardment of Fort Sumter in 1861, the B&O had been caught up in the tensions between the North and South.

In 1859, conductor A.J. Phelps sent a panicked telegram to Baltimore that read, in part, “Express train bound east under my charge was stopped this morning at Harpers Ferry by armed abolitionists. They have possession of the bridges and of the arms and armory of the United States.”

This was the beginning of John Brown’s ill-fated raid on Harpers Ferry and is often considered the first battle of the Civil War. Brown realized what Confederate generals would also come to see in a few years: If they could sever the B&O Railroad’s connection, they could cripple their enemy.

In 1860, President-Elect Abraham Lincoln made his way from Illinois to Washington, DC, for his inauguration. It was supposed to be a leisurely trip, but rumors began that Lincoln might face violence in pro-Southern Baltimore.

Lincoln’s schedule was adjusted so that his train arrived in Baltimore at 3 a.m. Horses quietly dragged Lincoln’s rail car along Pratt Street from the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore depot to the Camden Street depot, where it was transferred to the B&O line. The B&O then delivered the president-elect safely to Washington at 6 a.m.

Damages during the War

In the early years of the war, when Northern Virginia was contested territory, sections of the B&O that ran south of the Potomac River would sometimes be under Confederate control. Whenever this happened, the Confederate Army was sure to burn bridges and tear up tracks.

“Millions and millions and millions of dollars of damage was done to the railroad during the war,” Wilson says.

The B&O’s annual report for 1861 showed that it had been a particularly costly year for the railroad. Losses totaled 26 bridges nearly a mile in length, 102 miles of telegraph line, two water stations, and a lot of rolling stock lost because of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson.

On May 23, 1861, Jackson’s men shut down the B&O between Point of Rocks, 12 miles east of Harpers Ferry, and Cherry Run, 32 miles west of Harpers Ferry. Jackson captured 56 locomotives and more than 300 freight cars. Some of them were put into use with Confederate railroads, while the rest were kept at Martinsburg, Virginia.

The following month, at Martinsburg, Jackson’s men blew up the seven-span railroad bridge; 400 rail cars and 42 engines were destroyed. This represented a significant loss to the railroad and shut down the B&O for close to 10 months.

This turned out to be the Confederacy’s most successful action against the B&O. Though they recognized the importance of the railroad to war-time tactics, they were unable to permanently stop the B&O or match the railroad’s success with the Southern railroads.

Recognizing the importance of the B&O to its own success, the Union government dedicated brigades on the eastern and western ends of the line to protect the B&O from not only regular Confederate Army actions, but also raids from the growing number of ranger units.

Prosperity

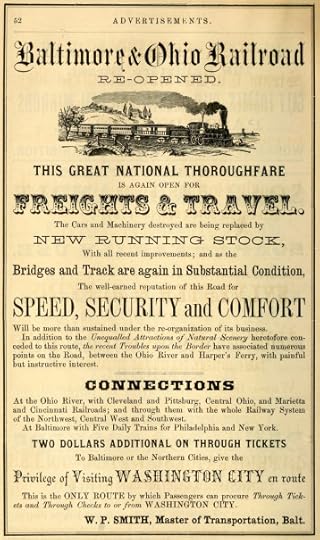

The relationship between the B&O and the Union proved beneficial to both. The Union was able to move its men and equipment quickly to where they were most needed.

For instance, when General William Rosecrans required back-up to defeat Confederate General Braxton Bragg in Georgia, help came from 30 trains pulling around 700 cars filled with 25,000 troops. They made a large part of the journey on the B&O.

For the B&O, revenues increased dramatically, and not just from its government contracts to provide transportation.

“Both passenger and freight revenue greatly increased between 1861 and 1865, passenger receipts increased more than fourfold in the four years, and freight revenue climbing nearly threefold,” Stover wrote.

“However, the 1861 revenue, partly because of the destruction caused by Stonewall Jackson, was much below that of previous years.”

Other stories of interest:

Thurmont loses its railroad station

Train crashes into county school bus killing seven children

The final trip of Maryland’s last interurban trolley