Sniff 'n' The Tears and "Driver's Seat": One-Hit Wonder? It's No Wonder

"The second album by this intellectual minded English ensemble is filled with the same kind of quality music that graced its debut last year. Writer / guitarist / vocalist / painter Paul Roberts is at the forefront, writing songs that are both heady in content and poignantly melodic. His songs have an eerie kind of esoteric quality to them."

— Billboard magazine, June 14, 1980

By Jim Thomsen

It's amazing to me how many pop and rock acts from the Seventies are still recording and releasing albums of new, original material.

Molly Hatchet? Still in business. America? Still at it. So is Foghat, and the Little River Band, and Kansas. Leo Freaking Sayer! Debby Effing Boone! Alan O'Day, whose one hit, "Undercover Angel," was released over thirty-four years ago, put out an album in 2008. Who buys an Alan O'Day album nowadays? (Hell, who bought one in 1977?)

Who buys any of these albums?

Well, people like me, that's who.

Because, to that list, add a band I love: Sniff 'n' the Tears.

Scratch your head for a minute as you think about that one. "Um … hmmmm … are you talking about the guys that did 'Driver's Seat'? Those guys are still around? Those one-hit wonders? Are you freaking kidding me?"

Yes. Yep. Yup. And nope.

I was in eighth grade, sporting headgear braces and Farrah Fawcett-feathered hair, when I first heard "Driver's Seat" on my AM/FM clock radio. I promptly ten-sped down to Steve Nicolet's Record Shack to procure the brand-spanking-new vinyl single with my newspaper bike-route money. I must have played it twenty-six times or more on my Sears belt-drive turntable before my mom called for me to come down to dinner. And then, I'm sure, I played it twenty-six times more as I did my algebra homework beneath the watchful eyes of my Steve Martin arrow-through-the-head poster. And probably 2,600 times since. As far as I'm concerned, "Driver's Seat" is the most insanely catchy song ever created.

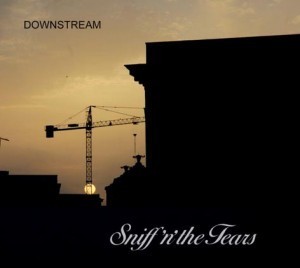

Now I'm less than two weeks shy of forty-six, with a stomach that slopes like a ski run, and temples shot through with tarnished silver. And as I write, I am listening to Downstream, the Sniff 'n' The Tears album released this spring, on my laptop computer. And it's good, and it's good for all the same reasons I eventually bought—and wore out—the first Sniff album, Fickle Heart, in 1978: Accessible songs, hook-riddled melodies and engagingly cryptic lyrics rendered in the pleasantly high, dry burr of founding member Paul Roberts' singing voice.

In fact, as probably the only person in North America who owns all seven Sniff albums (and the two Paul Roberts solo albums), I can authoritatively say that everything Paul Roberts has recorded is like that. The man simply has the gift for catchy, tuneful pop-rock songs with sly, intricate arrangements that bring out something new for the ear with each listen.

His songs are the equivalent of sliders at happy hour; cooked just right, slathered with the right condiments and chased with smartly selected aperitifs, they go down tasty and easy and not a bit greasy. They simply agree with me, and I could sample them all night long. (Which may or may not explain the sloping stomach.) They're not high cuisine, nor are they fast food. They're merely pretty good appetizers.

That said, I understand perfectly why Sniff 'n' the Tears, which put out four records between 1978 and 1982 before calling it quits (for the first time, that is), was a one-hit wonder.

One, nobody knew what they were or what scene they fit into. They were New Wave, sort of, a little, but not really (though anybody who heard the serenely spacy synthesizer solo near the end of "Driver's Seat" could be forgiven for thinking otherwise). They came from the London pub-rock scene that spawned Dire Straits, among others, but their pop songcraft was just a little too slick to be lumped in with the Dylanesque shuffle blues of Mark Knopfler & Co. They rocked, but not too hard, and in that regard they were as far away from being The Clash as they were Led Zeppelin. In short, they defied categorization. And, as any author pitching a book to a publisher knows, the inability to categorize is almost always the kiss of commercial death. Inevitably the bottom line is: "We love it, but we don't know how to sell it."

Two, their songs dwelled in a narrow, middling emotional range. They didn't reach for anthemic heights, nor did they produce their records with the propulsive dance-floor rhythms of the music that made the Top Forty in that time. There was no cohesive lyrical vision, merely Roberts' affably vague, vaguely sophisticated observations. Whether or not to try for bigger things was apparently a subject of constant tension between Roberts and the band's manager, Bud Prager (who was filling the same role with Foreigner, among others).

Roberts drily distills the debate about how to follow up the band's successful first album on the Sniff website: "Bud wanted the guy who was later to have huge success producing Bon Jovi. Bud felt that a big glossy rock sound with big choruses was what was required. It didn't occur to him that poodle rock might not be our natural constituency. For Bud, there was only one way to do it and that was the way Foreigner had done it.

"There were other bands from England that did not fit the template. I remember him saying, 'The Police will never make it in the States because Americans don't like reggae.'"

Roberts held out for his producer, a first-timer, and won. Or did he? He picks up the story: "At the studio, the reaction to the album was fantastic and certain light-headed feelings of vindication were beginning to set in. Until Bud Prager took me to one side. He said, 'Enjoy this evening, Paul, while you can. Everybody is telling you (that) you made a great album, but I've got to tell you it's a disaster. There is no hit single, no 'Driver's Seat.'"

Both were right. The Game's Up was a very good album, receiving positive reviews, and it remains Roberts' favorite. But it yielded no hits. While Sniff charted a handful of singles in Europe, it stiffed in North America and never again found so much as reliable distribution over here.

Three, there is the unsmall matter of Roberts' voice. I've spent more time than anybody ever should trying to find the words to describe this instrument, and what I've come down to is this: He sings like a man leaning against the outside of a nightclub at two in the morning, cupping a cigarette and a lighter in his hands as he sings alone, with a hint at an untapped well of unspeakable melancholy, to whatever traffic might be passing by.

It is a thin, scratchy, slightly hoarse instrument with a limited range that can't wail, soar or snarl with much credibility or cohesiveness. And yet, it is wonderfully expressive within that narrow corridor—dryly pained, dryly sardonic, dryly seductive, but oh, so distant. He sings like a man who is afraid to let loose everything he feels, or simply can't find his way to the fullest expression of his feelings, often floating his voice in a light croon or a dry whisper just behind a slow or midtempo beat.

He's not unlike other critically acclaimed singer-songwriters of the era I like and admire—Mark Knopfler, David Knopfler and Lloyd Cole among them. But none of those guys had much in the way of hits (Dire Straits had only a handful of Top Forty singles; it was one of the last album-rock-station sensations)—and one can't help but wonder if their too-cool-for-school singing styles, whether affected or genuine, didn't impact their fortunes on radio and in video.

That indifference can best be summed up by a single word spoken by a friend on a recent road trip through Oregon. I played the Fickle Heart CD all the way through, and toward the end, my friend asked who the artist was. I showed him the CD cover and asked him if he'd like me to burn him a copy. There was a moment of silence, then my friend handed me back the cover. "Eh," he said.

That didn't bother me—believe me, I get it that Sniff 'n' The Tears is an acquired taste—and I get the strong impression that it doesn't bother Paul Roberts, either.

In everything he's said and written on the subject, Roberts' attitude toward his fame—or lack of it—as a one-hit wonder can be summed up: "Oh, well." He didn't need music to make him whole; he's been married for nearly thirty years, has three grown daughters and a second career as a commercially successful painter.

Now sixty-two, he lives in Somerset, near London, and lives comfortably ("Driver's Seat" has made him a pretty penny on various reissues and commercial licensings for cars and stereo systems). He makes music when he feels like it (solo albums in 1985 and 1987; Sniff albums in 1991, 2001 and now 2011) and lives his life when he doesn't. You might say that on trouble and strife, he has another way of looking at life.

I'll tell you more about it next week … when I share an interview I recently conducted with the man himself.

In the meantime, enjoy one of Roberts' best atmospheric compositions.

Jim Thomsen is a freelance writer and manuscript copyeditor who lives near Seattle. His clients have included well-known crime authors Gregg Olsen, M. William Phelps and J.D. Rhoades. He is at work onThe Last Ferry of the Night, a literary crime novel, among other projects, but he could always use more work to pay the bills. Reach him at thomsen1965@gmail.com.