The Writer’s Dilemma. How Much Physical Description is Enough?

by Warren Adler @WarrenAdler

One of the imponderables of the fiction writing trade is just how much physical description is enough in order to fully flesh out a character’s identity. In years past many novels contained illustrations that purported to show images of the characters as conceived by the author.

One of the imponderables of the fiction writing trade is just how much physical description is enough in order to fully flesh out a character’s identity. In years past many novels contained illustrations that purported to show images of the characters as conceived by the author.

A prime example would be the work of Hablot Knight Brown “Phiz” who illustrated the works of Charles Dickens. Such illustrations were not mirror-image portrayals of Dickens’ characters but imaginary images conceived by the illustrator. Apparently Dickens, who approved the work of the artist, thought they were representative enough. Most storytellers compose their material as a kind

Most storytellers compose their material as a kind

of roadmap conceived in their imagination.Most storytellers from time immemorial compose their material as a kind of roadmap conceived in their imagination to communicate their vision to the imagination of the reader. The author’s expectation is that exposition, dialogue, character interaction, emotional contact, descriptive details of the environment, authorial insights, and perhaps a sketchy outline of the characters’ physiognomy are all enough to create an image of a character’s appearance in the reader’s mind.

The reader would be well aware of the approximate age of the characters by their impulses and desires, especially in those stories that deal with the mysteries of physical love and motivational impulses like ambition, faith, rapaciousness, depression, yearning and other emotions. In terms of the actual physical description, the physiognomy was and is often left to the reader’s imagination.

For example, in the Bible we are well aware of the characters and their motivations, but do we know what they really look like from the text? When we first encounter David, we know he is a young shepherd physically adroit, obviously chosen because he is skilled master of the slingshot.

With little physical details in the text, Michelangelo has imagined David as a stunning image carved in marble, fourteen feet tall. He is portrayed by the great sculptor as the most beautiful male figure on the planet, every part of him molded to represent the physical pinnacle of the gender.

Examples of such transference are legion. It is also true of the iconic painted and sculpted visions of Jesus Christ as an imagined human being and his depiction on the cross. Such physicality is not described anywhere in the new Testament.

There are so many examples of “left out physiognomy” descriptions that I’ll have to cherry-pick from my recollections.

Charles Swann and his mad passion for the courtesan Odette in Proust’s magnificent Swann’s Way is another interesting instance where the prime example of her physiognomy is Swann’s memory of Botticelli’s rendering of Moses’ first wife Zipporah.

Thus the reader must accept Swann’s memory of the painting, via the representation conceived by Botticelli, who imagined her from a brief mention in the old testament. Is anything more needed from Proust to fix Odette’s physical presence in one’s mind? Perhaps not.

Emma Bovary is another good example. Flaubert conceives of Emma with rich details of her psychology, her actions, even her inner thoughts, but the actual physical description is somewhat sketchy: black hair, big eyes, a birdlike walk. We know, of course, that she is a romantic, sexually frustrated and extravagant and obviously sensual and attractive but there are few concrete details.

Authors have little choice when their

Authors have little choice when their

books become movies.In today’s pop culture, the authors who have their books adapted to film have little choice but to accept the film makers’ physical version of their conceived characters. In Hemingway’s novels, for example, Gary Cooper was chosen to represent both Frederic Henry in “A Farewell to Arms” and Robert Jordan in “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” People of my generation have it fixed in our minds that Gary Cooper is the physical image of Hemingway’s conception.

The list of these “transferences” go on and on. Vivien Leigh is Scarlet O’Hara. Clark Gable personifies Rhett Butler. Did Margaret Mitchell conceive them physically as such? Detectives, cowboys, political figures, gangsters, courtesans, fairy tale characters, heroes and heroines of every conceivable category conceived in the imagination of authors are physically portrayed by actors. Indeed, this is not confined to fiction. “Based on a true story” has become a kind of logo to signify what is recycled as “real events.”

The question for the author is: how far he or she should go to individualize his or her character’s physical description? What is absolutely necessary for the depiction? Think of the possibilities. The color of the eyes, so varied and rich with meaning. The hair color: its length and style. The voice: its pitch, depth and rhythm. The skin hue: so fraught with genetic clues. The configuration of lips in a smile or pout. Height, posture, carriage, girth, age, gait, disfigurement, handicap and a limitless number of specific physical identifiers.

Is it a conscious decision of the author to leave out the physical descriptions deliberately to allow the reader to imagine his own images? As an author of many works of fiction, some highly descriptive of the characters’ physiognomy and some merely sketchy or non existent, I must confess that I am still somewhat ambivalent about such a choice but I raise the issue largely to solicit opinion from my fellow scribblers.

Just how much physical description is enough?

TWEETABLEThe Writer's Dilemma - How Much Physical Description is Enough? @WarrenAdler (Click to Tweet)

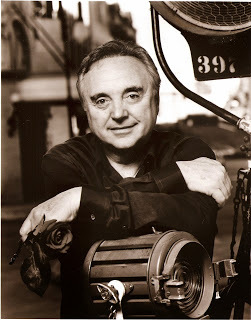

Warren Adler is best known for The War of the Roses, his masterpiece fictionalization of a macabre divorce turned into the Golden Globe and BAFTA-nominated dark comedy hit starring Michael Douglas, Kathleen Turner and Danny DeVito. In addition to the success of the stage adaption of his iconic novel on the perils of divorce, Adler has optioned and sold film rights to more than a dozen of his novels and short stories to Hollywood and major television networks. Warren Adler has just launched Writers of the World, an online community for writers to share their stories about why they began writing. Warren Adler's latest novel, Torture Man, which explores Jihadist terrorism, is available now. His Film/TV projects currently in development include the Hollywood sequel to The War of the Roses - The Children of the Roses, along with other projects including Capitol Crimes, a television series based on Warren Adler’s Fiona Fitzgerald mystery novels, as well as a feature film based on Warren Adler and James Humes’ WWII thriller, Target Churchill, in association with Myles Nestel and Lisa Wilson of The Solution Entertainment Group. Explore more at www.warrenadler.com and connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.

Warren Adler is best known for The War of the Roses, his masterpiece fictionalization of a macabre divorce turned into the Golden Globe and BAFTA-nominated dark comedy hit starring Michael Douglas, Kathleen Turner and Danny DeVito. In addition to the success of the stage adaption of his iconic novel on the perils of divorce, Adler has optioned and sold film rights to more than a dozen of his novels and short stories to Hollywood and major television networks. Warren Adler has just launched Writers of the World, an online community for writers to share their stories about why they began writing. Warren Adler's latest novel, Torture Man, which explores Jihadist terrorism, is available now. His Film/TV projects currently in development include the Hollywood sequel to The War of the Roses - The Children of the Roses, along with other projects including Capitol Crimes, a television series based on Warren Adler’s Fiona Fitzgerald mystery novels, as well as a feature film based on Warren Adler and James Humes’ WWII thriller, Target Churchill, in association with Myles Nestel and Lisa Wilson of The Solution Entertainment Group. Explore more at www.warrenadler.com and connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.

One of the imponderables of the fiction writing trade is just how much physical description is enough in order to fully flesh out a character’s identity. In years past many novels contained illustrations that purported to show images of the characters as conceived by the author.

One of the imponderables of the fiction writing trade is just how much physical description is enough in order to fully flesh out a character’s identity. In years past many novels contained illustrations that purported to show images of the characters as conceived by the author.A prime example would be the work of Hablot Knight Brown “Phiz” who illustrated the works of Charles Dickens. Such illustrations were not mirror-image portrayals of Dickens’ characters but imaginary images conceived by the illustrator. Apparently Dickens, who approved the work of the artist, thought they were representative enough.

Most storytellers compose their material as a kind

Most storytellers compose their material as a kind of roadmap conceived in their imagination.Most storytellers from time immemorial compose their material as a kind of roadmap conceived in their imagination to communicate their vision to the imagination of the reader. The author’s expectation is that exposition, dialogue, character interaction, emotional contact, descriptive details of the environment, authorial insights, and perhaps a sketchy outline of the characters’ physiognomy are all enough to create an image of a character’s appearance in the reader’s mind.

The reader would be well aware of the approximate age of the characters by their impulses and desires, especially in those stories that deal with the mysteries of physical love and motivational impulses like ambition, faith, rapaciousness, depression, yearning and other emotions. In terms of the actual physical description, the physiognomy was and is often left to the reader’s imagination.

For example, in the Bible we are well aware of the characters and their motivations, but do we know what they really look like from the text? When we first encounter David, we know he is a young shepherd physically adroit, obviously chosen because he is skilled master of the slingshot.

With little physical details in the text, Michelangelo has imagined David as a stunning image carved in marble, fourteen feet tall. He is portrayed by the great sculptor as the most beautiful male figure on the planet, every part of him molded to represent the physical pinnacle of the gender.

Examples of such transference are legion. It is also true of the iconic painted and sculpted visions of Jesus Christ as an imagined human being and his depiction on the cross. Such physicality is not described anywhere in the new Testament.

There are so many examples of “left out physiognomy” descriptions that I’ll have to cherry-pick from my recollections.

Charles Swann and his mad passion for the courtesan Odette in Proust’s magnificent Swann’s Way is another interesting instance where the prime example of her physiognomy is Swann’s memory of Botticelli’s rendering of Moses’ first wife Zipporah.

Thus the reader must accept Swann’s memory of the painting, via the representation conceived by Botticelli, who imagined her from a brief mention in the old testament. Is anything more needed from Proust to fix Odette’s physical presence in one’s mind? Perhaps not.

Emma Bovary is another good example. Flaubert conceives of Emma with rich details of her psychology, her actions, even her inner thoughts, but the actual physical description is somewhat sketchy: black hair, big eyes, a birdlike walk. We know, of course, that she is a romantic, sexually frustrated and extravagant and obviously sensual and attractive but there are few concrete details.

Authors have little choice when their

Authors have little choice when their books become movies.In today’s pop culture, the authors who have their books adapted to film have little choice but to accept the film makers’ physical version of their conceived characters. In Hemingway’s novels, for example, Gary Cooper was chosen to represent both Frederic Henry in “A Farewell to Arms” and Robert Jordan in “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” People of my generation have it fixed in our minds that Gary Cooper is the physical image of Hemingway’s conception.

The list of these “transferences” go on and on. Vivien Leigh is Scarlet O’Hara. Clark Gable personifies Rhett Butler. Did Margaret Mitchell conceive them physically as such? Detectives, cowboys, political figures, gangsters, courtesans, fairy tale characters, heroes and heroines of every conceivable category conceived in the imagination of authors are physically portrayed by actors. Indeed, this is not confined to fiction. “Based on a true story” has become a kind of logo to signify what is recycled as “real events.”

The question for the author is: how far he or she should go to individualize his or her character’s physical description? What is absolutely necessary for the depiction? Think of the possibilities. The color of the eyes, so varied and rich with meaning. The hair color: its length and style. The voice: its pitch, depth and rhythm. The skin hue: so fraught with genetic clues. The configuration of lips in a smile or pout. Height, posture, carriage, girth, age, gait, disfigurement, handicap and a limitless number of specific physical identifiers.

Is it a conscious decision of the author to leave out the physical descriptions deliberately to allow the reader to imagine his own images? As an author of many works of fiction, some highly descriptive of the characters’ physiognomy and some merely sketchy or non existent, I must confess that I am still somewhat ambivalent about such a choice but I raise the issue largely to solicit opinion from my fellow scribblers.

Just how much physical description is enough?

TWEETABLEThe Writer's Dilemma - How Much Physical Description is Enough? @WarrenAdler (Click to Tweet)

Warren Adler is best known for The War of the Roses, his masterpiece fictionalization of a macabre divorce turned into the Golden Globe and BAFTA-nominated dark comedy hit starring Michael Douglas, Kathleen Turner and Danny DeVito. In addition to the success of the stage adaption of his iconic novel on the perils of divorce, Adler has optioned and sold film rights to more than a dozen of his novels and short stories to Hollywood and major television networks. Warren Adler has just launched Writers of the World, an online community for writers to share their stories about why they began writing. Warren Adler's latest novel, Torture Man, which explores Jihadist terrorism, is available now. His Film/TV projects currently in development include the Hollywood sequel to The War of the Roses - The Children of the Roses, along with other projects including Capitol Crimes, a television series based on Warren Adler’s Fiona Fitzgerald mystery novels, as well as a feature film based on Warren Adler and James Humes’ WWII thriller, Target Churchill, in association with Myles Nestel and Lisa Wilson of The Solution Entertainment Group. Explore more at www.warrenadler.com and connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.

Warren Adler is best known for The War of the Roses, his masterpiece fictionalization of a macabre divorce turned into the Golden Globe and BAFTA-nominated dark comedy hit starring Michael Douglas, Kathleen Turner and Danny DeVito. In addition to the success of the stage adaption of his iconic novel on the perils of divorce, Adler has optioned and sold film rights to more than a dozen of his novels and short stories to Hollywood and major television networks. Warren Adler has just launched Writers of the World, an online community for writers to share their stories about why they began writing. Warren Adler's latest novel, Torture Man, which explores Jihadist terrorism, is available now. His Film/TV projects currently in development include the Hollywood sequel to The War of the Roses - The Children of the Roses, along with other projects including Capitol Crimes, a television series based on Warren Adler’s Fiona Fitzgerald mystery novels, as well as a feature film based on Warren Adler and James Humes’ WWII thriller, Target Churchill, in association with Myles Nestel and Lisa Wilson of The Solution Entertainment Group. Explore more at www.warrenadler.com and connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.

Published on April 23, 2016 01:00

No comments have been added yet.