After Frankenstein

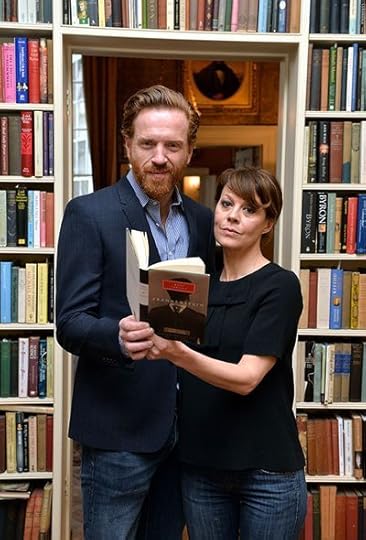

Damian Lewis and Helen McCrory; credit: Anthony Harvey/Getty Images

By SAMUEL GRAYDON

On entering 50 Albemarle Street, I felt as Ali Baba might have as the stone was rolled back from the mouth of the thieves��� cave. For an inconspicuous white town house, a minute���s walk from Green Park underground station, it certainly held more than its fair share of treasures. This was John Murray���s house and, from 1768 to 2002, it was the site of operations for the publisher that bears his name. I was directed up a wide staircase to the first floor where, in a room with grand bookshelves and gold wallpaper, lay a spread of tea, coffee, pastries and fruit (and, oddly, Bloody Marys). This was the ���Frankenstein Breakfast��� of the Keats-Shelley Memorial Association. Evidently, Frankenstein went for the Continental.

We were celebrating the winners of the 2016 Keats-Shelley Prize for poetry and essays on the theme ���After Frankenstein��� (for the bicentenary of the publication of Mary Shelley���s novel), and the winners of the Young Romantics Prize, for sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds, now in its second year. The Association had organized a reading, by the actors Helen McCrory and Damian Lewis, of extracts from Frankenstein intermingled with extracts from Shelley���s diary, arranged by the poet Pele Cox.

We assembled around the fireplace in which Byron���s manuscripts were burnt. Before the actors took the floor, the winner of the Young Romantics Prize, Riona Millar, aged sixteen, gave a reading of her sonnet, read under the watchful portraits of Coleridge, Byron and Thomas Gray:

Wreathed in laurels; glossy leaves unfurl, coiled,

The great pale gloaming thing unravels limbs,

Grins, hitches weeping gums wide, growling hymns,

Praising Father, Master, he who slaved, toiled

To build this monstrous structure ��� he is soiled

With these grimly yellowed stains, he who brims

With boundless love and wonder ��� awed, he skims

Round flat stones through his father���s throat ��� unspoiled.

The night, a temptress, plucks his peeling heart,

Wet, from his dappled chest, as moonlight blinds

Him; stumbling, mismatched, made up of spare parts

And engine oil. He trips, and falls. He finds

Great pale gloaming blooms that feed on the moon

He wakens not, with frail blossoms strewn.

This was swiftly followed by McCrory and Lewis���s performance, which, not unexpectedly, was captivating; Lewis emphasized the erudition and intelligence of the monster, and McCrory the coldness of Frankenstein: aspects of both characters that dramatizations of Shelley���s work often leave unexplored. Cox���s choice of extracts subtly drew out the shared role of the author and Frankenstein as ���creator���, allowing for a few moments when it was not apparent whether it was Shelley or her character who was speaking. But it is this plurality that plays such a part in Frankenstein���s success; man is monstrous and monsters humane ��� we are created and creators and we may hate and love in equal measure.

Listening to these readings, I was reminded that it is Frankenstein, and not "She Walks in Beauty", Don Juan, "To A Skylark", or even "Ozymandias" that is the best remembered work of all the writers who shared the Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva, 200 years ago. It would seem that it is easier to find an awesome terror in one���s own monstrosities than in the slopes of Mont Blanc, where Percy Bysshe Shelley discovered it.

And so, with sublime thoughts, I stepped out onto Albemarle Street again, leaving the treasures of the Romantics to themselves. I felt as though I should have said ���close sesame��� as I left.

Damian Lewis, Will Kemp, Riona Millar and Helen McCrory; credit: Anthony Harvey/Getty Images

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers