Dear Sean, We Need to Talk

3000 plus words—turn back now or read until the end…grab coffee now.

I have to have a conversation with chef Sean Brock. Sean, I hope you’re reading this. Immediately. Things have gotten out of hand in the discourse on “race” and Southern food and it’s time we hashed things out. One to one, personally, and have a hummus summit. (warning: satirical Israel/Palestine peace process reference) It doesn’t matter who made the hummus first or who made it better, or whose hummus is more authentic; the point is we both make hummus, we both love hummus and we want people to appreciate what hummus means to us and we want people to keep making hummus, secure in the knowledge that hummus is a part of everyone’s story and that hummus will endure.

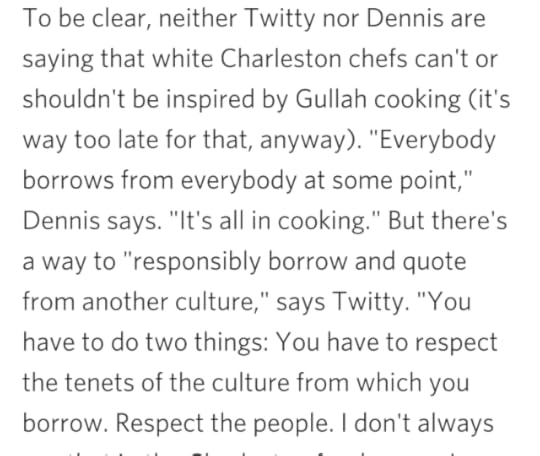

But we are not talking about hummus—we’re talking Southern food—and specifically we’re talking Lowcountry food and what Charleston brings to the table—we are talking power, access, and moving the conversation beyond triggers like “culinary appropriation,” into discussions of culinary justice, amplification, and social and political responsibility.

This is serious shite. We are long overdue for a summit Mr. Brock.

The past 24 hours have changed me. I can’t say for the better. Those who know me and my work know that I strive to choose a higher path—I am happy to be bound by Jewish law to look inside myself and weigh and judge my actions, thoughts and choices. G-d or no G-d, and maybe it doesn’t matter, I have a charge to keep and I find it difficult when the challenges to my identity, my work and my integrity force me to fight back and give retort. I should note with just a bit of irony the word for “war,” (milchama) and the word for “bread,” (lechem) in Hebrew share the same root (lchm). Bread—coded down to us from the days of old as both money and the basis sustenance—food—is often the place where conflicts begin and end.

This I will concede—and I may concede nothing else—you and your fellow chefs have the right to “do you,” however you please. You can cook whatever you want, call it whatever you want, stand tall in your convictions and communicate the message you want on your own terms and charge what you will for the experience. It is not my prerogative to circumscribe your potential or curtail your growth or trajectory. My advocacy was but a whisper once upon a time and I could be easily ignored but now it has gained traction and perhaps now you will incline your ear and listen to what I have to say—as an equal with my own place at the table—earned in cuttings of cane, burns, cuts, pounds of cotton and hands of tobacco and sowings of rice. I have stirred the pot, putting myself in the footsteps of those many of your leaders do acknowledge and do write about—even if I wonder to what end. The research, recreation and interpretation of enslaved people’s food is not personally or communally easy—and it goes beyond creativity and taste—it is in many ways a willed descent into hell. I assure you it is taxing, painful and revelatory—but I have no choice—as you have no choice but to be who I was created to be.

But like my spiritual Ancestor, Esther ha-Malkah, I come on this day, the 13th of the moon-time of Adar in the year 5776 to plead for myself and for my people. My people are the living and the dead—and unfortunately, the dying. In 2006 I touched the saltwater at Sullivan’s Island for the first time. It was my first engagement with the place that many have called “The Ellis Island of Black America.” I was corrected by Marquetta Goodwine, “Queen Quet,” to many that no—this was no Ellis Island. Despite the fact that roughly the same number of European immigrants had come through Ellis in relation to enslaved Africans who came through Sullivan’s—roughly 40ish percent…that’s abstractly 4 out of every African Americans who can trace an ancestor back to that one spot—these were enslaved people, not people looking for a better life.

It was at that moment, ten years ago I sank to my knees in the wet sand, fully clothed and guaranteeing my jeans would be stained—and humbled myself before my dead. At the time I did not know where they came from or who was there—I just knew this was where I had to start. You know Sullivan’s Island—its bordered by condominiums and would be nothing if the Revolutionary War and Civil War had not left their marks there. Even though this space is as important as any Charleston antebellum mansion—piazza and all—its not a million dollar space—its just a plaque and a bench lovingly donated by nobel prize winner Toni Morrison.

Unfortunately, and you can’t change this—and neither can I—this is how my America begins—not with opportunity—but with chains—and not just then—an aftermath—a legacy, a chronic illness carried in body, spirit, soul, and mind—systemic racism, racial class disparities, political disenfranchisement, violence and terrorism—both from state and rogue citizen. That’s my heritage—triumph and uplift tempered by this—chains linking me back to my father’s first father and my mother’s first mother—who stepped off the boat and went to the plague house at Sullivan’s only to await sale not very far from where Husk is today. I am proud to tell you I am an Akan many times over and I am a Mende—a son of rice growers through Sierra Leone leading backwards to the grandeur of Old Mali and beyond that to West African prehistory on the river Niger. I have no names for them—until I die I never will.

When I kneeled—I was told I had to work in the fields, I had to stir the pots, that it was not enough to sit in an armchair and pontificate or grow things as a hobby—these things—you well know—have been done—and often not well—and they don’t serve any of us to any real end. What I endured for their sake—at their command—compares not with five minutes in their lives—and I can honestly say—I would refuse five minutes in their hell. I have it easy. But the hard work taught me to respect those who do the hard work today—who struggle to keep our culture going, who stress and swear because there seems to be no hope in sight. This is for the ramen-eaters, for the food desert nomads, for the kids who cannot take my journey, for the parent who wants to teach our story and pass it on but doesn’t know how to start, where to begin or what to say. My burden is in some ways heavier than yours—and that’s not your fault, but if you care so deeply for this food and where it comes from—and I know you do, you will help me lift a corner of this burden. I know you already do some of this locally–I want to seek a way to do this on a larger scale.

My greatest sin in the Eater piece—as I was quoted by my mishpocheh Hillary Drixler—was calling the “scene,” out to begin to explore a self-directed path of culinary reparations—for a more open engagement with a Black community that is special, unique and proud. Yes stories of great Black historic chefs are being told, and menus are steeped in history and ingredients are telling stories about the people of the past and your menu supports Southern businesses and there are fledgling discussions on how to increase Black traffic in downtown restaurants and putting more Black cooks and culinarians out into the scene. These are the claims at least…I love David Shield’s dedication and sincerity—but even he admitted to me that my nudge and the nudges of others helped opened the minds of many to greater community engagement. And yet–Charleston has a long way to go before it is a center of culinary justice as well as the scene that you and others have obviously worked hard to put on the map. The frustrating thing is that it could be such a city.

When I last visited Charleston I went with Chef BJ Dennis to a food spot where the owner and her customers gave me an earful. She made it clear that Gullah based establishments were often passed up in favor of traditional white owned restaurants in Charleston and that the local African American community did not always do its part to look after its own. One gentlemen—and they ALL know BJ, made sure to tell him before he left, “Remember what I told you, we are not Lowcountry, WE ARE GULLAH.” Then came the refrain—“to the bone.” There are quiet and hidden currents of differing opinions that won’t be heard in mixed company. This is the way –as we both know–of the South.

The cure is to not lie or obfuscate. The cure is to bear witness, to be real, to be truthful. The way to change our fate is to change the names we give and take, to re-arrange our place, to change our deeds, to pray yes, but also to give back and to cry out. (I thank the Rabbis of antiquity for this formula.) My path is not one of quiet acceptance but of a heritage born of the ring shout, forged in blood, sweat and tears in the slave quarter. This is why I cook.

Your colleagues who critiqued the Eater piece thought my comments were personal—and they were not. I salute you for going to Senegal to learn more–but that’s your job. I was annoyed and confused when certain articles deemed you “the white chef version of Henry Louis Gates Jr.” (of Finding Your Roots fame). I disagree with some of your supporters when they assume that the spotlight put on your search for inspiration and ideas is on an “overgrown path”—when African, African American and Afro-Caribbean and Latino culinarians have been writing about these connections and celebrating them without you—and without any media coverage for quite some time. Pierre Thiam’s Yolele and my Fighting Old Nep pre-dated your trip to Senegal—but nobody lauded us for making the connection—nobody said we were exploring “unchartered territory,” nobody said we were going where nobody had ever thought to go. This trickles down—because people will then ask culinarians of color—“How is what you’re doing different from what Sean Brock is already doing?” See—I’m not pissed off at you because I don’t know if you sanction that or not—it’s just already we are being taxed out of the intellectual real estate that is our inheritance. Gentrification is as much creative and mental as it is physical. That article and the Food and Wine piece that followed it was confusing and problematic for a lot of Black culinarians—but we collectively kept our mouths shuts in the best tradition of wearing the mask.

Nobody hates you–nobody hates Andy or Rick–we just want equal opportunity of agency. There is no reason to assume otherwise.

I do not know why you chose not to introduce me at MAD at the last moment or why I have seen you multiple times since and yet you have not spoken to me. I have eaten your food—and your Mother’s food–supported your restaurant in Nashville, I even reached out to you in 2012 when I was a nothing—a nobody—looking to dialogue with you about a little project I was doing called The Cooking Gene. I never heard back after an initial email exchange brokered by a mutual friend. I saw you make jokes on social media—but I desperately wanted to sit down with Sean Brock—to see if you were my blood, my cousin, my kinsman. I have tried to reach out, and my intentions are to squash these feelings of mistrust I am trying to shake.

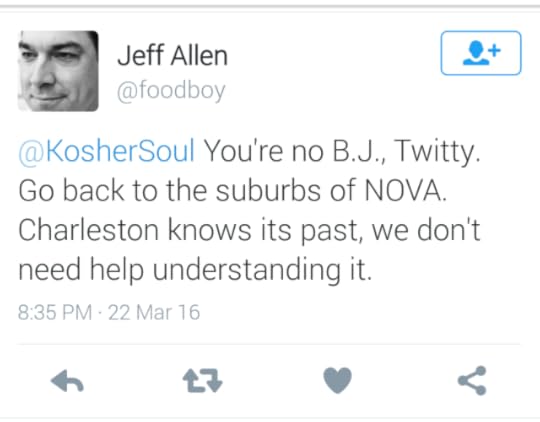

I still do feel the need to reach out but the reaction to my quotes in Hillary Drixler’s Eater piece was swift and harsh—the tone was one of putting me in my place. Despite the fact that Matt Hartman of Durham wrote a very clear, eloquent argument making many of the same points I did—I was singled out for much harsher and direct criticism than was Matt. The wagons were circled. People who I thought knew me well enough to pick up the phone or email me were insinuating that I was nothing short of a culinary carpetbagger a stranger, a fool sent to spread divisive misinformation about a model food scene above the fray of other issues in the world of Southern food—of acknowledging the African presence and agency. I was called out on Twitter—not as Michael Twitty, our colleague—our fellow Southern striver and historian–a man in search of his roots and those of his people and all Southerners–but as @koshersoul the stranger—the disrespectful “comeya”—an invasive voice alongside the soothing peacemaker Chef BJ Dennis. Not cool.

Backs have been turned to me and ears have been closed. Chris Haire said he had no interest in reading Matt Harman’s piece. Where is the reciprocity? Why should one side listen if the other does not? I said “I will not speculate on why Matt Harman has not receved the critique I have.” I didn’t want to even be on record as assuming anything—race—class-sexual orientation—where I live—etc. Chris shot back that I was injecting race. There is it—the new way to diminish our messages—“race baiting,” being “divisive.” We’re tired of this—really tired. B’rer Fox set a good example though didn’t he? Put the tar doll up people will punch before they think. He currently believes I just “half talk out of your ass.” (his words) Oh well. Not everybody has to like you. I’m not in this to avoid critique, but I won’t be called out of my name.

Hanna Raskin and Kinsey Gidick explained what they felt the article’s shortcomings were via the article’s comments section—but in my opinion, they resorted to classic defense mechanisms—progress is slow but its coming…but what’s worse:

(How do you respond to that?)

Then comes the call out—“The interpretation offered up by Michael Twitty is applicable to many places; its possibly even applicable to the Charleston Wine + Food Festival, which Hillary attended. But if she had interviewed a few more Charlestonians who identify as Gullah, she would have discovered that the racial issues plaguing Charleston aren’t rooted in culinary appropriation. The real concern is not giving credit to African American for rice and okra: That’s well underway in better dining rooms. It’s giving them jobs (and critically, promotions.) It’s giving them a warm welcome to restaurants that re now patronized almost exclusively by white people.”

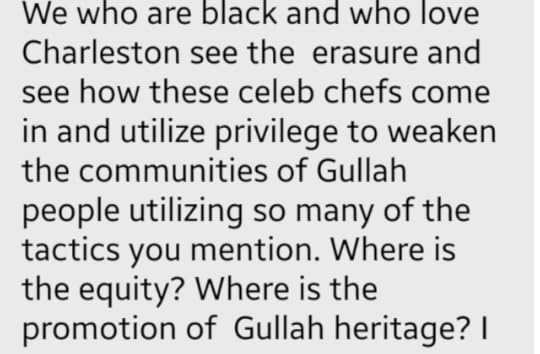

And yet I got this message the same day from one of many Black Charlestonians who reached out:

Anyone who has heard me speak or read my writings knows that’s a straw man if you ever heard of one…Michael Twitty is apparently not interested cooperative economics, diversifying the kitchen, improving opportunities for more brick and mortar Black restaurants and education within his own community—he’s just whining about a boutique rice originally revived to feed ducks—and later re-booted as food for elite humans-just like a 150 years ago. Its not just the ingredients–its stories, messages, marketing–but …Oy, zenug ist zenug.

If I was that simple and boring—I wouldn’t be where I am and all of you know that. Hanna, do not our sages teach to judge the whole of the human favorably (machrio l’chaf zechut)?

Tweets were exchanged—condescension mixed with a flurry of stereotypes—I’m apparently ill-informed, incapable of making and following a logical argument, and at worst a social-media aggressive. It’s not fair to my character, because some of these same people saw me take my time to talk to students in Charleston in a school for behaviorally challenged youth…these are people who have eaten my cooking and watched me sweat on a plantation under a hot sun. These are people who know I have seed collections and have consulted for the best of the best—people who have heard me give the exact same messages at MAD in Copenhagen, in London at the Barbican Theater, at Oxford University and on the stage of TED in Vancouver. It was not that my message had changed, it was that my platform was now here—not there—and that I was not indicting the “scene,” for erasure of the Black presence in the past—it was not sharing the benefits of the now and this is the crux of the Hartman article–and my advocacy.

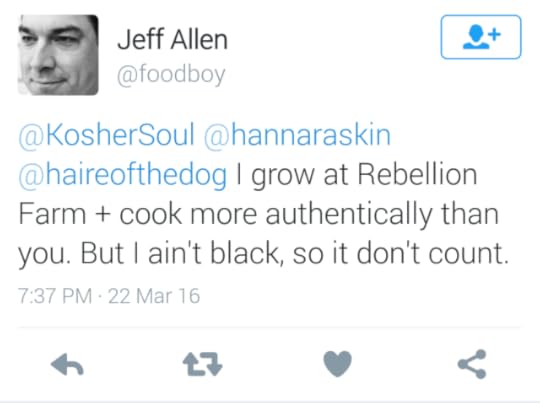

Any of these people—or the whole lot of them could have called me—emailed me—asked to speak privately or put out something that might correct what they saw as an imbalance—but they chose to attempt to muddle my message, marginalize me, and malign by character and intent. Did they feel I did this to their Charleston? No clear answers on that–and no personal outreach. They are still going as I write this. This is extremely disheartening and discouraging. This is not what we need in the current political climate. One tweet from Jeff Allen said “I cook more authentically than you. But I ain’t black, so it don’t count.” Ok so I never said you had to be black to make this food–but if people want to play that old game–they can. The Eater article is clear–I never said that–it explicitly says I don’t harbor that sentiment.

Is this the best we can do in dialogue about what food and identity and meaning are really all about?

Hanna Raskin ‘ s response was “those aren’t the words I would have chosen…” which begs the question, what words were more suitable?

Sean, we, the descendants of these Africans are dying. We are dying of stress and chronic health ailments rooted in diet and quality of food and access. We are in need of economic opportunity and food is such an important gateway for that. We are dying of police bullets and terrorist bullet and many don’t really give a fuck. We are joining our Ancestors faster than we should and as our Rome burns other people’s Rome rises. This is why I’m hot. This is why I cook. This is why I insist on my right of return as the descendant of Charleston’s enslaved and of the rice growers that gave the Lowcountry a story to sell. The South shall rise again, but will we? We need economic development, food justice—and most of all we refuse to be put at the periphery of our narrative when we should remain at its center. I know that you know this is what I’m fighting for sure as BJ and many others have for years.

This isn’t technically your responsibility, but if part of our story is in your hands, so too must be part of a solution.

Sean—if you want to cook sometime let’s do it. If you want to talk sometime let’s do it. We will not agree on everything—nor should we. I have hard questions for you. You have hard questions for me. We are both sincere. But this I know—we are here at this moment on this planet, sharing this heritage for a reason—and we must not waste the opportunity.

Your friend in skillet—your cousin in mind—The Antebellum Chef, Michael W. Twitty, grandson of a great living South Carolinian—Gonze Lee Twitty, founding member, Federation of Southern Cooperatives.

Michael W. Twitty's Blog

- Michael W. Twitty's profile

- 323 followers