Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 62

April 10, 2018

Two Souls: when introverts write about divas, a guest post by Mary Sharratt, author of Ecstasy

I'm pleased to welcome Mary Sharratt back to Reading the Past. Her new novel Ecstasy, set in a richly imagined fin-de-siècle Vienna, focuses on Alma Schindler Mahler, a bold, musically gifted woman controversial in her own time as well as ours. I especially enjoyed its depiction of Alma's passionate nature and her struggles to define herself with regard to her considerable talents and her relationships with men. Ecstasy is published today by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Welcome, Mary!

~

Two Souls: When Introverts Write about Divas

Mary Sharratt

Alma Schindler Mahler, the heroine of my new novel Ecstasy, was everything I am not. She was larger than life. An exuberantly extroverted diva. The It-Girl of fin de siècle Vienna. When Alma stepped into the salon in her white crepe-de-chine gown, the air crackled with electricity, so mesmerizing was her presence. Artists, architects, and poets vied for her attention.

Alma Schindler Mahler, the heroine of my new novel Ecstasy, was everything I am not. She was larger than life. An exuberantly extroverted diva. The It-Girl of fin de siècle Vienna. When Alma stepped into the salon in her white crepe-de-chine gown, the air crackled with electricity, so mesmerizing was her presence. Artists, architects, and poets vied for her attention.

Gustav Klimt chased her across Italy to give her her first kiss when she was just a teenager. Gustav Mahler fell in love with her at a dinner party and proposed only weeks later.

Her subsequent husbands and lovers included Bauhaus-founder Walter Gropius, artist Oskar Kokoschka, and poet Franz Werfel. But she was her own woman to the last, polyamorous long before it was cool, one of the most controversial women of her time.

I, however, am a wallflower. At parties, I struggle with small talk. I don’t covet Alma’s impressive list of paramours either, as much as I respect these men. I’ve been happily, faithfully married for nearly thirty years. While I certainly don’t judge or begrudge Alma for her adventures, I love my quiet married life.

Personality-wise, I have far more in common with Alma’s first husband, Gustav Mahler. Not that I presume to claim his level of genius—far from it. But he was an introvert after my own heart. In the woods near their summer home on Lake Wörthersee in Austria, he build a composing hut where he spent his mornings composing in pristine solitude. No one was allowed to disturb his creative trance. To me that sounds like heaven on earth.

Some Mahlerites blame Alma for his downfall. Despite the fact that Mahler died aged fifty of a hereditary heart condition, they appear to believe that Alma’s adulterous affair with Walter Gropius hastened Mahler’s demise. I think the most fanatical Almaphobes would love nothing better than to dig her out of her grave in Vienna’s Grinzing Cemetery and burn her remains at the stake for her perceived sins against Mahler.

Yet Mahler loved Alma as passionately as some of his fans seem to hate her. We can feel her indelible presence in his music from his Fifth Symphony onward. His most tender adagios are declarations of his devotion to her. In his tenth and final symphony, we can literally hear his heart breaking for her. He scrawled on the score, “To live for you, to die for you, Almschi.”

How could one woman could inspire such extreme emotional reactions? In the popular imagination Alma is the mercurial femme fatale. A voracious, man-eating seductress. But I knew there had to be so much more to her.

The introvert in me saw Alma’s other side—her secret self hidden in the pages of her diary. This Alma was a cerebral and paradoxically lonely young woman. Though lacking in formal education, she devoured philosophy books and avant-garde literature. She was a most accomplished pianist—her teacher thought she was good enough to study at Vienna Conservatory. However, Alma didn’t want a career of public performance. Instead she yearned to be a composer. Her lieder, composed under the guidance of her mentor and lover, Alexander von Zemlinsky, are arresting, emotional, and highly original and can be compared with the early work of Zemlinsky’s other famous student, Arnold Schoenberg.

But the odds were stacked against her. Women who strived for a livelihood in the arts were mocked as the “third sex”—the fate of Alma’s friend, the sculptor Ilse Conrat. When a towering genius like Mahler asked Alma to give up her composing career as a condition of their marriage, she reluctantly succumbed.

Yet underneath it all she was still that questing young woman who yearned to compose symphonies and operas. Shortly before her marriage, twenty-two-year-old Alma wrote in her diary, “I have two souls: I know it.” Born in an era that struggled to recognize women as full-fledged human beings, Alma experienced a fundamental split in her psyche—the rift between herself as a distinct creative individual and herself as an object of male desire. The suppression of her true self to become the woman Mahler wanted her to be was unsustainable and inhuman. Eventually the authentic Alma erupted out of this false persona.

What emerged was a woman far ahead of her time, who rejected the shackles of condoned feminine behavior and insisted on her sexual and creative freedom. Alma eventually returned to composing and went on to publish fourteen of her songs. Three other lieder have been discovered posthumously. Now her work is regularly performed and recorded.

Like unconventional women throughout history, Alma to this day faces a backlash of misinterpretation and outright condemnation. She was complex, transgressive, ambitious, and often perplexing.

Which leads us back to why introverts write about divas. The Urban Dictionary defines a diva as a woman who exudes great style and confidence and expresses her unique personality without letting others define who she should be. A diva is a woman who stands in her sovereignty and blazes a trail for other women. Even introverts like me need to claim our inner diva to truly dance in our power.

Delving into Alma’s complexities allowed me to embrace all the shadows and light in my own character. For Alma was neither a “good” woman nor a “bad” woman, but a woman who insisted on being fully human, whatever the cost. A woman who recognized that pure and impure, faithful and loose, madonna and whore are simply poisonous projections used to deny women their full expression of being. Alma was not any one color, dark or light. She was the whole spectrum. So it is with all of us. Regardless whether we’re cloistered introverts or glamorous socialites, every woman contains the totality, the heights and the depths.

This is why Alma deserves to be the center of her own story. She was not only a composer but what in German is called a Lebenskünstlerin, or life artist—she pioneered new ways of being as a woman that was in itself a work of art.

~

Mary Sharratt is on a mission to write women back into history. Her novel Ecstasy is published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Visit her website: www.marysharratt.com

~

Two Souls: When Introverts Write about Divas

Mary Sharratt

Alma Schindler Mahler, the heroine of my new novel Ecstasy, was everything I am not. She was larger than life. An exuberantly extroverted diva. The It-Girl of fin de siècle Vienna. When Alma stepped into the salon in her white crepe-de-chine gown, the air crackled with electricity, so mesmerizing was her presence. Artists, architects, and poets vied for her attention.

Alma Schindler Mahler, the heroine of my new novel Ecstasy, was everything I am not. She was larger than life. An exuberantly extroverted diva. The It-Girl of fin de siècle Vienna. When Alma stepped into the salon in her white crepe-de-chine gown, the air crackled with electricity, so mesmerizing was her presence. Artists, architects, and poets vied for her attention.Gustav Klimt chased her across Italy to give her her first kiss when she was just a teenager. Gustav Mahler fell in love with her at a dinner party and proposed only weeks later.

Her subsequent husbands and lovers included Bauhaus-founder Walter Gropius, artist Oskar Kokoschka, and poet Franz Werfel. But she was her own woman to the last, polyamorous long before it was cool, one of the most controversial women of her time.

I, however, am a wallflower. At parties, I struggle with small talk. I don’t covet Alma’s impressive list of paramours either, as much as I respect these men. I’ve been happily, faithfully married for nearly thirty years. While I certainly don’t judge or begrudge Alma for her adventures, I love my quiet married life.

Personality-wise, I have far more in common with Alma’s first husband, Gustav Mahler. Not that I presume to claim his level of genius—far from it. But he was an introvert after my own heart. In the woods near their summer home on Lake Wörthersee in Austria, he build a composing hut where he spent his mornings composing in pristine solitude. No one was allowed to disturb his creative trance. To me that sounds like heaven on earth.

Some Mahlerites blame Alma for his downfall. Despite the fact that Mahler died aged fifty of a hereditary heart condition, they appear to believe that Alma’s adulterous affair with Walter Gropius hastened Mahler’s demise. I think the most fanatical Almaphobes would love nothing better than to dig her out of her grave in Vienna’s Grinzing Cemetery and burn her remains at the stake for her perceived sins against Mahler.

Yet Mahler loved Alma as passionately as some of his fans seem to hate her. We can feel her indelible presence in his music from his Fifth Symphony onward. His most tender adagios are declarations of his devotion to her. In his tenth and final symphony, we can literally hear his heart breaking for her. He scrawled on the score, “To live for you, to die for you, Almschi.”

How could one woman could inspire such extreme emotional reactions? In the popular imagination Alma is the mercurial femme fatale. A voracious, man-eating seductress. But I knew there had to be so much more to her.

The introvert in me saw Alma’s other side—her secret self hidden in the pages of her diary. This Alma was a cerebral and paradoxically lonely young woman. Though lacking in formal education, she devoured philosophy books and avant-garde literature. She was a most accomplished pianist—her teacher thought she was good enough to study at Vienna Conservatory. However, Alma didn’t want a career of public performance. Instead she yearned to be a composer. Her lieder, composed under the guidance of her mentor and lover, Alexander von Zemlinsky, are arresting, emotional, and highly original and can be compared with the early work of Zemlinsky’s other famous student, Arnold Schoenberg.

But the odds were stacked against her. Women who strived for a livelihood in the arts were mocked as the “third sex”—the fate of Alma’s friend, the sculptor Ilse Conrat. When a towering genius like Mahler asked Alma to give up her composing career as a condition of their marriage, she reluctantly succumbed.

Yet underneath it all she was still that questing young woman who yearned to compose symphonies and operas. Shortly before her marriage, twenty-two-year-old Alma wrote in her diary, “I have two souls: I know it.” Born in an era that struggled to recognize women as full-fledged human beings, Alma experienced a fundamental split in her psyche—the rift between herself as a distinct creative individual and herself as an object of male desire. The suppression of her true self to become the woman Mahler wanted her to be was unsustainable and inhuman. Eventually the authentic Alma erupted out of this false persona.

What emerged was a woman far ahead of her time, who rejected the shackles of condoned feminine behavior and insisted on her sexual and creative freedom. Alma eventually returned to composing and went on to publish fourteen of her songs. Three other lieder have been discovered posthumously. Now her work is regularly performed and recorded.

Like unconventional women throughout history, Alma to this day faces a backlash of misinterpretation and outright condemnation. She was complex, transgressive, ambitious, and often perplexing.

Which leads us back to why introverts write about divas. The Urban Dictionary defines a diva as a woman who exudes great style and confidence and expresses her unique personality without letting others define who she should be. A diva is a woman who stands in her sovereignty and blazes a trail for other women. Even introverts like me need to claim our inner diva to truly dance in our power.

Delving into Alma’s complexities allowed me to embrace all the shadows and light in my own character. For Alma was neither a “good” woman nor a “bad” woman, but a woman who insisted on being fully human, whatever the cost. A woman who recognized that pure and impure, faithful and loose, madonna and whore are simply poisonous projections used to deny women their full expression of being. Alma was not any one color, dark or light. She was the whole spectrum. So it is with all of us. Regardless whether we’re cloistered introverts or glamorous socialites, every woman contains the totality, the heights and the depths.

This is why Alma deserves to be the center of her own story. She was not only a composer but what in German is called a Lebenskünstlerin, or life artist—she pioneered new ways of being as a woman that was in itself a work of art.

~

Mary Sharratt is on a mission to write women back into history. Her novel Ecstasy is published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Visit her website: www.marysharratt.com

Published on April 10, 2018 07:00

April 5, 2018

Researching and Writing Historical Fiction, a guest post by Elaine Neil Orr

Today I have a short post by Elaine Neil Orr, whose new novel Swimming Between Worlds (Berkley, April), set in Nigeria and in North Carolina during the Civil Rights Movement, is one I'll be reviewing in May.

~

Researching and Writing Historical FictionElaine Neil Orr

I don’t wait to finish research before I start writing. I start in tandem, perhaps because writing itself is the spark for me. Very soon, however, the research process begins and sparks begin to fly. I find that even the least digging into the soil of the past yields riches.

I don’t wait to finish research before I start writing. I start in tandem, perhaps because writing itself is the spark for me. Very soon, however, the research process begins and sparks begin to fly. I find that even the least digging into the soil of the past yields riches.

One of my favorite forms of research is to go there. My first novel, A Different Sun: a Novel of Africa, is inspired by the journal of a nineteenth century missionary woman. I journeyed to the places she had lived and traveled in the mid-nineteenth century in what is present-day Nigeria.

I wanted to see what varieties of native trees she had seen. Was the land that met her eyes hilly or flat? Were there outcroppings of rock? Where was the nearest stream? (I knew there was an historical marker where she and her husband had begun their first Sunday School.)

With Swimming Between Worlds, my new novel set in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, I was able to travel often. My home in Raleigh is less than two hours away. The novel is set in the late 1950s and 60s in an early suburb of the city, where craftsman and Victorian houses line curvilinear streets.

Photo of Tacker's house (Swimming Between Worlds)

Photo of Tacker's house (Swimming Between Worlds)

Walking, I began to feel my story in the muscles of my legs! Because the novel covers a year, I drove over in every season, observing the dogwoods in their annual course, smelling fires coming from chimneys in the winter, listening to music wafting from open windows in the spring.

The lunch-counter sit-ins of the early Civil Rights Movement are a catalyst for the three major characters in the novel. I peered into the windows of the old Woolworths building, imagining where the counter had been, with the chrome and vinyl stools.

The tactile, sensory nature of this research brings me into a kind of communion with my character that I don’t think I could achieve without going there. I feel a spiritual connection. There is something transporting about being there. For me, it’s what brings the story to life.

~

About Swimming Between Worlds: Tacker Hart left his home in North Carolina as a local high school football hero, but returns in disgrace after being fired from a prestigious architectural assignment in West Africa. Yet the culture and people he grew to admire have left their mark on him. Adrift, he manages his father's grocery store and becomes reacquainted with a girl he barely knew growing up.

Kate Monroe's parents have died, leaving her the family home and the right connections in her Southern town. But a trove of disturbing letters sends her searching for the truth behind the comfortable life she's been bequeathed.

Elaine Neil Orr

Elaine Neil Orr

(credit: Elizabeth Galecke

Photography)On the same morning but at different moments, Tacker and Kate encounter a young African-American, Gaines Townson, and their stories converge with his. As Winston-Salem is pulled into the tumultuous 1960s, these three Americans find themselves at the center of the civil rights struggle, coming to terms with the legacies of their pasts as they search for an ennobling future.

Elaine Neil Orr is professor of English at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, where she teaches world literature and creative writing. She also serves on the faculty of the low-residency MFA in Writing program at Spalding University in Louisville. Author of A Different Sun, two scholarly books, and the memoir Gods of Noonday: A White Girl's African Life, she has been a featured speaker and writer-in-residence at numerous universities and conferences and is a frequent fellow at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She grew up in Nigeria. Visit her website at http://www.elaineneilorr.com.

~

Researching and Writing Historical FictionElaine Neil Orr

I don’t wait to finish research before I start writing. I start in tandem, perhaps because writing itself is the spark for me. Very soon, however, the research process begins and sparks begin to fly. I find that even the least digging into the soil of the past yields riches.

I don’t wait to finish research before I start writing. I start in tandem, perhaps because writing itself is the spark for me. Very soon, however, the research process begins and sparks begin to fly. I find that even the least digging into the soil of the past yields riches.One of my favorite forms of research is to go there. My first novel, A Different Sun: a Novel of Africa, is inspired by the journal of a nineteenth century missionary woman. I journeyed to the places she had lived and traveled in the mid-nineteenth century in what is present-day Nigeria.

I wanted to see what varieties of native trees she had seen. Was the land that met her eyes hilly or flat? Were there outcroppings of rock? Where was the nearest stream? (I knew there was an historical marker where she and her husband had begun their first Sunday School.)

With Swimming Between Worlds, my new novel set in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, I was able to travel often. My home in Raleigh is less than two hours away. The novel is set in the late 1950s and 60s in an early suburb of the city, where craftsman and Victorian houses line curvilinear streets.

Photo of Tacker's house (Swimming Between Worlds)

Photo of Tacker's house (Swimming Between Worlds)Walking, I began to feel my story in the muscles of my legs! Because the novel covers a year, I drove over in every season, observing the dogwoods in their annual course, smelling fires coming from chimneys in the winter, listening to music wafting from open windows in the spring.

The lunch-counter sit-ins of the early Civil Rights Movement are a catalyst for the three major characters in the novel. I peered into the windows of the old Woolworths building, imagining where the counter had been, with the chrome and vinyl stools.

The tactile, sensory nature of this research brings me into a kind of communion with my character that I don’t think I could achieve without going there. I feel a spiritual connection. There is something transporting about being there. For me, it’s what brings the story to life.

~

About Swimming Between Worlds: Tacker Hart left his home in North Carolina as a local high school football hero, but returns in disgrace after being fired from a prestigious architectural assignment in West Africa. Yet the culture and people he grew to admire have left their mark on him. Adrift, he manages his father's grocery store and becomes reacquainted with a girl he barely knew growing up.

Kate Monroe's parents have died, leaving her the family home and the right connections in her Southern town. But a trove of disturbing letters sends her searching for the truth behind the comfortable life she's been bequeathed.

Elaine Neil Orr

Elaine Neil Orr(credit: Elizabeth Galecke

Photography)On the same morning but at different moments, Tacker and Kate encounter a young African-American, Gaines Townson, and their stories converge with his. As Winston-Salem is pulled into the tumultuous 1960s, these three Americans find themselves at the center of the civil rights struggle, coming to terms with the legacies of their pasts as they search for an ennobling future.

Elaine Neil Orr is professor of English at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, where she teaches world literature and creative writing. She also serves on the faculty of the low-residency MFA in Writing program at Spalding University in Louisville. Author of A Different Sun, two scholarly books, and the memoir Gods of Noonday: A White Girl's African Life, she has been a featured speaker and writer-in-residence at numerous universities and conferences and is a frequent fellow at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She grew up in Nigeria. Visit her website at http://www.elaineneilorr.com.

Published on April 05, 2018 04:00

March 31, 2018

12 intriguing upcoming historical novels for my 12th blogiversary and Women's History Month

It's the last day of March, so I'm getting this in under the wire. Reading the Past turned twelve last week, and I've been too busy with library work to post about it until now. In acknowledgment, and in celebration of Women's History Month, here are a dozen new and upcoming historical novels by women that are on my wishlist.

In 14th-century London, an illuminated Book of Hours is commissioned, deeply affecting the lives, hopes, and ambitions of three people. Medieval-set novels are few and far between these days, and I'm looking forward to this one. HarperCollins Australia, April. [see on Goodreads]

Again, coincidentally, a novel revolving around three people's lives - but this time set in coastal Scotland during WWII, as friendships are formed among different social classes, and people reinvent themselves in wartime. HarperCollins UK, April. [see on Goodreads]

In the late 15th century, a wealthy man drowns in an isolated Somerset village, the cause unknown, and the village priest is pressured to figure out the cause, and the possible perpetrator. This sounds like a worthwhile combination of literary fiction and mystery, set in a quiet place where much is happening beneath the surface. Jonathan Cape, March. [see on Goodreads]

A new Kearsley novel is something to celebrate. Bellewether (which I have a hard time remembering how to spell) centers on a forbidden romance set during wartime in 18th-century North America. Sourcebooks, Aug. [see on Goodreads]

Kim's debut was The Calligrapher's Daughter, set over several decades in early 20th-century Korea. Her second novel moves ahead in time and follows two sisters separated by the Korean War. The blurb mentions it was inspired by a true story. HMH, November. [see on Goodreads]

McMahon's novels are classified as literary fiction, but the ones I've read also have a strong suspense/mystery thread. Her latest is about three women, two world wars, resistance, and the legacy of betrayal. W&N, June. [see on Goodreads]

Anne O'Brien has written many novels about notable Englishwomen whose lives went unremarked by history, as well as others more well-known. Her latest focuses on Elizabeth Mortimer, a member of the Plantagenet clan of medieval England, who married Harry "Hotspur" Percy, Duke of Northumberland. HQ, May. [see on Goodreads]

This new novel promises an original combination of settings: 1930s Brazil, Rio, and Hollywood during its Golden Age. It focuses on the unlikely friendship/rivalry between two ambitious, musically talented women. Riverhead, August. [see on Goodreads]

I'd enjoyed Riordan's Fiercombe Manor, published when "house" sagas were highly popular. Her latest is a Gothic suspense novel set in wartime Cornwall. Michael Joseph, March. [see on Goodreads]

Rizzuto's new literary historical novel is a saga focusing on twin sisters in 1950s-60s Hawaii, their mother, and a betrayal that changes their lives; the blurb says it's set against an "epic sweep of history," moving from WWII Japan to 1970s NYC. Grand Central, May. [see on Goodreads]

Roy's novel examines mid-20th-century India through the stories of a man who uncovers his artist mother's itinerant life through India and Bali, as he searches for the reasons she left her family behind. MacLehose, June. [see on Goodreads]

Though best known in the US for her novel Please Look After Mom, South Korean writer Shin's novel about a Korean orphan and court dancer who falls in love with a French diplomat during the Belle Epoque was written first; it's based on a true story. Pegasus, Aug. [see on Goodreads]

In 14th-century London, an illuminated Book of Hours is commissioned, deeply affecting the lives, hopes, and ambitions of three people. Medieval-set novels are few and far between these days, and I'm looking forward to this one. HarperCollins Australia, April. [see on Goodreads]

Again, coincidentally, a novel revolving around three people's lives - but this time set in coastal Scotland during WWII, as friendships are formed among different social classes, and people reinvent themselves in wartime. HarperCollins UK, April. [see on Goodreads]

In the late 15th century, a wealthy man drowns in an isolated Somerset village, the cause unknown, and the village priest is pressured to figure out the cause, and the possible perpetrator. This sounds like a worthwhile combination of literary fiction and mystery, set in a quiet place where much is happening beneath the surface. Jonathan Cape, March. [see on Goodreads]

A new Kearsley novel is something to celebrate. Bellewether (which I have a hard time remembering how to spell) centers on a forbidden romance set during wartime in 18th-century North America. Sourcebooks, Aug. [see on Goodreads]

Kim's debut was The Calligrapher's Daughter, set over several decades in early 20th-century Korea. Her second novel moves ahead in time and follows two sisters separated by the Korean War. The blurb mentions it was inspired by a true story. HMH, November. [see on Goodreads]

McMahon's novels are classified as literary fiction, but the ones I've read also have a strong suspense/mystery thread. Her latest is about three women, two world wars, resistance, and the legacy of betrayal. W&N, June. [see on Goodreads]

Anne O'Brien has written many novels about notable Englishwomen whose lives went unremarked by history, as well as others more well-known. Her latest focuses on Elizabeth Mortimer, a member of the Plantagenet clan of medieval England, who married Harry "Hotspur" Percy, Duke of Northumberland. HQ, May. [see on Goodreads]

This new novel promises an original combination of settings: 1930s Brazil, Rio, and Hollywood during its Golden Age. It focuses on the unlikely friendship/rivalry between two ambitious, musically talented women. Riverhead, August. [see on Goodreads]

I'd enjoyed Riordan's Fiercombe Manor, published when "house" sagas were highly popular. Her latest is a Gothic suspense novel set in wartime Cornwall. Michael Joseph, March. [see on Goodreads]

Rizzuto's new literary historical novel is a saga focusing on twin sisters in 1950s-60s Hawaii, their mother, and a betrayal that changes their lives; the blurb says it's set against an "epic sweep of history," moving from WWII Japan to 1970s NYC. Grand Central, May. [see on Goodreads]

Roy's novel examines mid-20th-century India through the stories of a man who uncovers his artist mother's itinerant life through India and Bali, as he searches for the reasons she left her family behind. MacLehose, June. [see on Goodreads]

Though best known in the US for her novel Please Look After Mom, South Korean writer Shin's novel about a Korean orphan and court dancer who falls in love with a French diplomat during the Belle Epoque was written first; it's based on a true story. Pegasus, Aug. [see on Goodreads]

Published on March 31, 2018 09:00

March 29, 2018

A Reckoning by Linda Spalding, a literary exploration of antebellum America and slavery's consequences

Spalding’s timely, historically sensitive sequel to The Purchase (2013), a literary saga which also confidently stands alone, explores the ramifications of slavery on the next generation of the Dickinson family.

Spalding’s timely, historically sensitive sequel to The Purchase (2013), a literary saga which also confidently stands alone, explores the ramifications of slavery on the next generation of the Dickinson family.An abolitionist’s arrival on their southwestern Virginia farm in 1855 sparks the dissolution of their longtime way of life. Some enslaved men escape. Without their labor, the crops fail and money grows tight, fomenting conflict between circuit-riding preacher John and his cruel half-brother, Benjamin, who owns their land and slaves.

The narrative then turns adventurous as it follows several people, including John’s wife, Lavina, 13-year-old son, Martin, and an escaped slave, Bry, as their journeys away from Jonesville unite and diverge.

The characters are full-fledged individuals whose mind-sets reflect their time and place. John is enamored of their African American housekeeper and imagines she loves him in return, while Lavina is an intriguing mix of independence and feminine conformity.

For John’s family, it’s also noteworthy that the unspoiled American landscape, spectacularly described in its glory and dangers, offers a spirituality and freedom absent from his controlling form of religion.

Linda Spalding's A Reckoning was published on March 13th by Pantheon in the US. The Canadian publisher is McClelland & Stewart. I reviewed it for Booklist's March 15th issue, after having reviewed the initial novel, The Purchase, back in 2013. The Purchase had won Canada's Governor General's Literary Award in 2012, and I actually think A Reckoning is the better of the two.

Other notes:

- For readers who enjoy literary sagas, the characters are based on people from the author's family history (her family name is Dickinson).

- The novel's dialogue isn't given in quotation marks, which may turn off some readers. That said, this isn't uncommon for literary fiction, and I didn't have trouble distinguishing who said what.

Published on March 29, 2018 05:00

March 26, 2018

The Tuscan Child by Rhys Bowen, a novel of secrets, wartime danger, and culinary delights in scenic Tuscany

The Tuscan Child marks my first experience reading one of Rhys Bowen’s adult novels even though she’s written many, primarily mysteries. However, when I was in middle and high school, I was a fan of the Sweet Dreams teenage romances and have fond memories of them, including the ones written by Bowen under her real name.

The Tuscan Child marks my first experience reading one of Rhys Bowen’s adult novels even though she’s written many, primarily mysteries. However, when I was in middle and high school, I was a fan of the Sweet Dreams teenage romances and have fond memories of them, including the ones written by Bowen under her real name. Both foodies and anyone dreaming of a vacation in scenic Italy should be drawn to The Tuscan Child. It fits in with two historical fiction trends – multi-period novels about secrets from the past, and World War II – and its locale and plot twists add originality.

In 1973, following some personal trauma, Joanna Langley returns home to Surrey after getting notified of her father’s unexpected death. Sir Hugo Langley had been a baronet, but financial hardship had forced him to sell the family estate, Langley Hall, years ago. Now it’s a girls’ boarding school, which Joanna attended growing up; Sir Hugo had worked as the art master there while living with his wife and daughter in the gatekeeper’s lodge. A mystery unfolds when Joanna goes through her father’s effects and finds a love letter he wrote, in Italian, addressed to “Mia carissima Sofia” and referring to “their beautiful boy,” whose whereabouts he kept secret. The letter had been returned to sender.

Joanna knows that Sir Hugo, a former RAF pilot, had flown WWII bombing missions and was injured after being shot down but never spoke about it. Needless to say, an unknown half-brother is quite a surprise. Joanna has little to go on but, determined to find him, she packs up and travels to Italy for answers. Her story alternates with Hugo’s nearly thirty years earlier, as he parachutes out of a damaged plane, conceals himself in crumbling monastery ruins near the Tuscan village of San Salvatore, and is aided by a young mother, Sofia, whose husband is missing in action.

Bowen made feel I was there alongside Hugo—cold, feverish, and creatively devising sources of shelter and food—and Joanna, experiencing a sense of freedom in the sun-dappled Tuscan hills. Both father and daughter find themselves in life-threatening situations: he from the Germans, and she because soon after she arrives, she learns someone doesn’t want old secrets uncovered.

The suspenseful aspects are counterbalanced by the mouthwatering recipes (Joanna’s landlady is a talented cook who wants to fatten her up so she'll find a husband) and depictions of the picturesque Tuscan countryside, with its rows of olive trees, rocky crags, and ocher-colored roofs. The Tuscan Child isn’t a mystery by genre; the plot is rather sedate at times. Still, Bowen’s deep roots in the genre are noticeable. I admired one plot twist, since I would have found it nearly impossible to predict.

Despite some stereotypical personalities, I enjoyed spending time in San Salvatore and recommend the book to anyone who wants to “travel by novel.”

I reviewed this novel from a NetGalley copy.

Published on March 26, 2018 07:38

March 23, 2018

Writing Novels about Victorian Theatre, a guest post by Christina Britton Conroy

I'm pleased to have actor, singer, and historical novelist Christina Britton Conroy joining me today at Reading the Past for a fascinating post about the lives of actors in Victorian times and after. She has a new four-book series, set in the theatrical world of Victorian and Edwardian England, just out from Endeavour Press.

~

Writing Novels about Victorian TheatreChristina Britton Conroy

Having spent my early life as a professional singer/actor, it is no wonder I chose the Victorian theatre to set my 4-book series His Majesty's Theatre. Pouring through real and fictional theatrical accounts, I am especially fond of Charles Dickens' Nicholas Nickleby and Clarence Dane's Broom Stages (rereleased as Theatre Royal). Extensive study in London libraries completed my research. Actors who were not yet, or never would become, stars usually struggled to afford a dry roof and enough food to keep from starving. Theatrical boarding houses were few and far between, for good reason. If tickets didn't sell, and/or a shady producer took off before paying his actors, midnight flits out back windows were commonplace. Even legitimate producers were allowed to withhold salaries if a performance was cancelled because of natural causes.

At least jobs for actors were plentiful. Experience was seldom a prerequisite for hiring. Actor-manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree was the first to teach acting technique. In 1904, his classed evolved into the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. Most actors learned on-the-job. Tree built Her Majesty's Theatre in 1887. When Edward VII was crowned in 1901, the theatre name was changed to His Majesty's.

Most actors were expected to learn their roles from sides (sheets with only their own lines on the page). They provided their own costumes, wigs, and makeup. There are accounts of dancing girls spending most of their hard-earned wages replacing torn stockings.

In small road companies, the actors were also the backstage crew, setting up their stage, rigging, lights, making and mending costumes, and roaming each new town, passing out tear sheets and selling tickets. A newly hired actor could be expected to learn several long roles almost instantly, rehearse night and day, and still have enough energy to project his/her voice over a rowdy audience. If a small company played a town for 8 days, they need to perform 8 different plays. Old actors could seldom stand these rigors, so young actors drew overlarge wrinkles onto smooth brows, powered dark hair to make it gray, walked bent over, and tried to look old.

In small road companies, the actors were also the backstage crew, setting up their stage, rigging, lights, making and mending costumes, and roaming each new town, passing out tear sheets and selling tickets. A newly hired actor could be expected to learn several long roles almost instantly, rehearse night and day, and still have enough energy to project his/her voice over a rowdy audience. If a small company played a town for 8 days, they need to perform 8 different plays. Old actors could seldom stand these rigors, so young actors drew overlarge wrinkles onto smooth brows, powered dark hair to make it gray, walked bent over, and tried to look old.

The few star actors and actor-managers like Henry Irving, and Herman Beerbohm Tree made vast salaries, built their own theatres, and treated their actors fairly. They also took their companies on tours of the world.

Many well paid "tragic actors" took time from the legitimate theatre to play Pantomimes. These elaborately silly holiday children's shows rehearsed for 3-4 weeks, opened on Boxing Day (December 26th) and played for several weeks. Rehearsals were not paid, but actors could still earn more in a short Pantomime season than an entire year playing small roles for Henry Irving.

Learning all this quaint information made me shake my head. Being an actor is 2018 is very similar. The major difference is that now, there is less work for actors.

I was lucky to get a union card at the age of 7. Actors Equity Association demands producers pay a bond before a show goes into production. This ensures that actors will be paid and brought home, even if a show closes out of town. Rehearsal and performance hours are still long, but reasonable. Even working in summer stock, when one show is playing 8-9 performances a week, and two more shows are rehearsing during offstage hours, the actors and crew are guaranteed 11 hours off after an evening curtain falls and rehearsal can begin the next day. Contracts vary according to the budget of the theatre, but breaks for meals, warm dressing rooms in winter, and other basic necessities are guaranteed.

Non-union theatres still do whatever they want. The only nonunion gig I played was Jenny Lind in Barnum on a cruise ship. There were no unions on the high seas. The play alternated nights with a Las Vegas-type revue called Sea Legs. I was horrified when a new Sea Legs number was put into that show and the dancers were rehearsed all night, after the Barnum curtain came down. They were allowed a couple hours sleep before the next Barnum matinee. Since that is a circus show, with some dancers swinging on ropes over the audience, it was amazing no one got hurt.

Non-union theatres still do whatever they want. The only nonunion gig I played was Jenny Lind in Barnum on a cruise ship. There were no unions on the high seas. The play alternated nights with a Las Vegas-type revue called Sea Legs. I was horrified when a new Sea Legs number was put into that show and the dancers were rehearsed all night, after the Barnum curtain came down. They were allowed a couple hours sleep before the next Barnum matinee. Since that is a circus show, with some dancers swinging on ropes over the audience, it was amazing no one got hurt.

In 2018, every theatre performer wants to be on Broadway. The work is hard, but salaries and perks are high. Walking through Times Square, pedestrians are accosted by attractive young people costumed from a current show, handing out fliers. These actors are never in Broadway shows, but may be in Off Broadway shows playing just around the corner.

Much like 19th-century Pantomime stars, modern TV/film stars performing on Broadway take huge cuts in their usual salaries. One female star told an interviewer she was paying her nanny more that she was taking home in her pay envelope.

The summer stock season of 1988, I was cast in The Women. The show is about the scandal of divorce in the 1930s. Since regional theatre producers can ask actors to provide their own clothes for contemporary plays, they decided to set the play in 1988. When the director arrived, reminded them there was no scandal of divorce in 1988 and the play would be nonsense, most contemporary clothes brought by the actors didn't work. Anticipating the problem, I brought clothes that worked for both periods. The rest of the cast scrambled, sent home for other clothes and went shopping.

We were always paid on a Friday, and the last show of the week was on Sunday. Before the very last Sunday show, we had not been paid. One of our stars, Julie Newmar (best remembered as Cat Woman), refused to go on until we were all paid. Thanks to Julie and the Equity bond, we were paid and flown home to New York.

Reference: Jackson, Russell, Victorian Theatre (A & C Black, London, 1989).

Christina Britton Conroy, M.A., C.M.T., L.C.A.T.

www.ChristinaBrittonConroy.com

~

Novelist / screenwriter / singer / actor / Irish harpist / Certified Music Therapist / Licensed Creative Arts Therapist Christina Britton Conroy has many passions.

Novelist / screenwriter / singer / actor / Irish harpist / Certified Music Therapist / Licensed Creative Arts Therapist Christina Britton Conroy has many passions.

A classically trained singer/actor, Christina toured the globe singing operas, operettas, and musicals. She soloed with orchestras, oratorio societies, at Radio City Music Hall, and folk venues, accompanying herself on the guitar and Irish Harp. Her theatrical credits include: On the Twentieth Century, directed by Harold Prince, with Rock Hudson, Imogene Coca, and Judy Kaye; The Women with Anita Gillette, Dody Goodman, Julie Newmar, Virginia Graham, Jane Kean, and Margaux Hemingway; and the original Actors Studio production of Let ‘em Rot by Cy Coleman, directed by Morton DaCosta.

As a Certified Music Therapist and Licensed Creative Arts Therapist, Christina has enriched the lives of children, adults, their families, and caregivers. She is also the Founder and Executive Director of Music Gives Life, bring musical performing into the lives of senior citizens. NY1 - TV NEWS named her NYer Of The Week. Christina's education includes creative writing and screenwriting at NYU; acting at The Actors' Studio and NY School of Film and Television; Music at Juilliard Pre-College, Interlochen, a music bachelors from U. of Toronto, and music therapy MA from NYU.

OnlineBookClub reviewers wrote: "If you love to read about Downton Abbey era England as much as I do, you are in for a real treat with Christina Britton Conroy’s, Not From The Stars, Book 1 of His Majesty’s Theatre series. This story has all the requirements of a Shakespearian play; star-crossed lovers, controlling fathers, and cruel betrothal arrangements…" (Endeavour Press, UK 11/2017). The original novel, now a 4-book series, was a Fountainhead Writing Contest finalist.

Christina lives in Greenwich Village, NYC with her husband, actor/media-coach, Larry Conroy.

For more information on her historical novel series, His Majesty’s Theatre:

NOT FROM THE STARS, http://www.amazon.com/dp/B074VCVWSF

BUT FROM THINE EYES, http://www.amazon.com/dp/B075NHD6L5

TRUTH AND BEAUTY, http://www.amazon.com/dp/B076M1MX7D

BEAUTY’S DOOM, http://www.amazon.com/dp/B0783HLFXV

~

Writing Novels about Victorian TheatreChristina Britton Conroy

Having spent my early life as a professional singer/actor, it is no wonder I chose the Victorian theatre to set my 4-book series His Majesty's Theatre. Pouring through real and fictional theatrical accounts, I am especially fond of Charles Dickens' Nicholas Nickleby and Clarence Dane's Broom Stages (rereleased as Theatre Royal). Extensive study in London libraries completed my research. Actors who were not yet, or never would become, stars usually struggled to afford a dry roof and enough food to keep from starving. Theatrical boarding houses were few and far between, for good reason. If tickets didn't sell, and/or a shady producer took off before paying his actors, midnight flits out back windows were commonplace. Even legitimate producers were allowed to withhold salaries if a performance was cancelled because of natural causes.

At least jobs for actors were plentiful. Experience was seldom a prerequisite for hiring. Actor-manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree was the first to teach acting technique. In 1904, his classed evolved into the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. Most actors learned on-the-job. Tree built Her Majesty's Theatre in 1887. When Edward VII was crowned in 1901, the theatre name was changed to His Majesty's.

Most actors were expected to learn their roles from sides (sheets with only their own lines on the page). They provided their own costumes, wigs, and makeup. There are accounts of dancing girls spending most of their hard-earned wages replacing torn stockings.

In small road companies, the actors were also the backstage crew, setting up their stage, rigging, lights, making and mending costumes, and roaming each new town, passing out tear sheets and selling tickets. A newly hired actor could be expected to learn several long roles almost instantly, rehearse night and day, and still have enough energy to project his/her voice over a rowdy audience. If a small company played a town for 8 days, they need to perform 8 different plays. Old actors could seldom stand these rigors, so young actors drew overlarge wrinkles onto smooth brows, powered dark hair to make it gray, walked bent over, and tried to look old.

In small road companies, the actors were also the backstage crew, setting up their stage, rigging, lights, making and mending costumes, and roaming each new town, passing out tear sheets and selling tickets. A newly hired actor could be expected to learn several long roles almost instantly, rehearse night and day, and still have enough energy to project his/her voice over a rowdy audience. If a small company played a town for 8 days, they need to perform 8 different plays. Old actors could seldom stand these rigors, so young actors drew overlarge wrinkles onto smooth brows, powered dark hair to make it gray, walked bent over, and tried to look old.The few star actors and actor-managers like Henry Irving, and Herman Beerbohm Tree made vast salaries, built their own theatres, and treated their actors fairly. They also took their companies on tours of the world.

Many well paid "tragic actors" took time from the legitimate theatre to play Pantomimes. These elaborately silly holiday children's shows rehearsed for 3-4 weeks, opened on Boxing Day (December 26th) and played for several weeks. Rehearsals were not paid, but actors could still earn more in a short Pantomime season than an entire year playing small roles for Henry Irving.

Learning all this quaint information made me shake my head. Being an actor is 2018 is very similar. The major difference is that now, there is less work for actors.

I was lucky to get a union card at the age of 7. Actors Equity Association demands producers pay a bond before a show goes into production. This ensures that actors will be paid and brought home, even if a show closes out of town. Rehearsal and performance hours are still long, but reasonable. Even working in summer stock, when one show is playing 8-9 performances a week, and two more shows are rehearsing during offstage hours, the actors and crew are guaranteed 11 hours off after an evening curtain falls and rehearsal can begin the next day. Contracts vary according to the budget of the theatre, but breaks for meals, warm dressing rooms in winter, and other basic necessities are guaranteed.

Non-union theatres still do whatever they want. The only nonunion gig I played was Jenny Lind in Barnum on a cruise ship. There were no unions on the high seas. The play alternated nights with a Las Vegas-type revue called Sea Legs. I was horrified when a new Sea Legs number was put into that show and the dancers were rehearsed all night, after the Barnum curtain came down. They were allowed a couple hours sleep before the next Barnum matinee. Since that is a circus show, with some dancers swinging on ropes over the audience, it was amazing no one got hurt.

Non-union theatres still do whatever they want. The only nonunion gig I played was Jenny Lind in Barnum on a cruise ship. There were no unions on the high seas. The play alternated nights with a Las Vegas-type revue called Sea Legs. I was horrified when a new Sea Legs number was put into that show and the dancers were rehearsed all night, after the Barnum curtain came down. They were allowed a couple hours sleep before the next Barnum matinee. Since that is a circus show, with some dancers swinging on ropes over the audience, it was amazing no one got hurt.In 2018, every theatre performer wants to be on Broadway. The work is hard, but salaries and perks are high. Walking through Times Square, pedestrians are accosted by attractive young people costumed from a current show, handing out fliers. These actors are never in Broadway shows, but may be in Off Broadway shows playing just around the corner.

Much like 19th-century Pantomime stars, modern TV/film stars performing on Broadway take huge cuts in their usual salaries. One female star told an interviewer she was paying her nanny more that she was taking home in her pay envelope.

The summer stock season of 1988, I was cast in The Women. The show is about the scandal of divorce in the 1930s. Since regional theatre producers can ask actors to provide their own clothes for contemporary plays, they decided to set the play in 1988. When the director arrived, reminded them there was no scandal of divorce in 1988 and the play would be nonsense, most contemporary clothes brought by the actors didn't work. Anticipating the problem, I brought clothes that worked for both periods. The rest of the cast scrambled, sent home for other clothes and went shopping.

We were always paid on a Friday, and the last show of the week was on Sunday. Before the very last Sunday show, we had not been paid. One of our stars, Julie Newmar (best remembered as Cat Woman), refused to go on until we were all paid. Thanks to Julie and the Equity bond, we were paid and flown home to New York.

Reference: Jackson, Russell, Victorian Theatre (A & C Black, London, 1989).

Christina Britton Conroy, M.A., C.M.T., L.C.A.T.

www.ChristinaBrittonConroy.com

~

Novelist / screenwriter / singer / actor / Irish harpist / Certified Music Therapist / Licensed Creative Arts Therapist Christina Britton Conroy has many passions.

Novelist / screenwriter / singer / actor / Irish harpist / Certified Music Therapist / Licensed Creative Arts Therapist Christina Britton Conroy has many passions.A classically trained singer/actor, Christina toured the globe singing operas, operettas, and musicals. She soloed with orchestras, oratorio societies, at Radio City Music Hall, and folk venues, accompanying herself on the guitar and Irish Harp. Her theatrical credits include: On the Twentieth Century, directed by Harold Prince, with Rock Hudson, Imogene Coca, and Judy Kaye; The Women with Anita Gillette, Dody Goodman, Julie Newmar, Virginia Graham, Jane Kean, and Margaux Hemingway; and the original Actors Studio production of Let ‘em Rot by Cy Coleman, directed by Morton DaCosta.

As a Certified Music Therapist and Licensed Creative Arts Therapist, Christina has enriched the lives of children, adults, their families, and caregivers. She is also the Founder and Executive Director of Music Gives Life, bring musical performing into the lives of senior citizens. NY1 - TV NEWS named her NYer Of The Week. Christina's education includes creative writing and screenwriting at NYU; acting at The Actors' Studio and NY School of Film and Television; Music at Juilliard Pre-College, Interlochen, a music bachelors from U. of Toronto, and music therapy MA from NYU.

OnlineBookClub reviewers wrote: "If you love to read about Downton Abbey era England as much as I do, you are in for a real treat with Christina Britton Conroy’s, Not From The Stars, Book 1 of His Majesty’s Theatre series. This story has all the requirements of a Shakespearian play; star-crossed lovers, controlling fathers, and cruel betrothal arrangements…" (Endeavour Press, UK 11/2017). The original novel, now a 4-book series, was a Fountainhead Writing Contest finalist.

Christina lives in Greenwich Village, NYC with her husband, actor/media-coach, Larry Conroy.

For more information on her historical novel series, His Majesty’s Theatre:

NOT FROM THE STARS, http://www.amazon.com/dp/B074VCVWSF

BUT FROM THINE EYES, http://www.amazon.com/dp/B075NHD6L5

TRUTH AND BEAUTY, http://www.amazon.com/dp/B076M1MX7D

BEAUTY’S DOOM, http://www.amazon.com/dp/B0783HLFXV

Published on March 23, 2018 05:00

March 21, 2018

Tempest by Beverly Jenkins, an engaging Old West romance

Regan Carmichael’s first meeting with her intended husband, Dr. Colton Lee, starts off with a bang—literally. After foiling a recent attack along her journey from Arizona, Regan shoots Colt by accident, mistaking him for another outlaw.

Regan Carmichael’s first meeting with her intended husband, Dr. Colton Lee, starts off with a bang—literally. After foiling a recent attack along her journey from Arizona, Regan shoots Colt by accident, mistaking him for another outlaw.Set in 1880s Wyoming, this engaging last volume in Jenkins’ African-American Old West romance trilogy shows how their relationship ripens into deep, abiding love. This is a classic mail-order bride story with some original touches—for one, Regan is a wealthy heiress.

Despite their awkward beginning, Regan and Colt soon come to appreciate each other’s qualities. Colt is a caring physician with a six-year-old daughter, Anna, whose spirit was crushed by an older relative; the unconventional Regan shows her stepdaughter how to have fun.

Refreshingly, the novel avoids contrived misunderstandings between the couple. The historical background, full of details on small-town life and dramas, showcases the West’s multicultural settlement, including the bigotry that Chinese miners faced. One subplot emphasizes the importance of education, a worthy subject.

A skilled shot, rider, and cook, and gorgeous to boot, Regan seems a bit idealized, and I wondered why a woman of her financial status would risk marrying a stranger. Still, the story and its likable characters kept me happily reading to the end.

Tempest was published by Avon on January 30 ($7.99/CA$9.99), and I reviewed it for the Historical Novels Review. This is the third book in the author's Old West series, after Breathless and Forbidden. It stands well on its own, although motivations for Regan's decisions may have been given in the previous book, which tells the love story of her aunt, Eddy. Her sister, Portia, was the heroine of the first book.

Jenkins writes historical romance featuring African-American characters (she also writes contemporaries) and is a multi-award winning author, having won the Nora Roberts Lifetime Achievement Award from the Romance Writers of America in 2017.

Published on March 21, 2018 06:44

March 16, 2018

Laura Purcell's The Silent Companions, an eerie multi-period ghost story, plus giveaway

The editor’s note at the beginning of my e-ARC of The Silent Companions begins with a warning: don’t read this book at night. Well, I did, and lived to tell about it – although I found myself looking askance at the dolls on my dresser before scuttling under the covers and turning off the light.

The editor’s note at the beginning of my e-ARC of The Silent Companions begins with a warning: don’t read this book at night. Well, I did, and lived to tell about it – although I found myself looking askance at the dolls on my dresser before scuttling under the covers and turning off the light. After writing two excellent fictional accounts of the Georgian royals, Laura Purcell has gone full-blown gothic for her third novel, a spooky read set in an English village in Victorian times and the 17th century. Her heroine is Mrs. Elsie Bainbridge, whose terrible story unfolds as she, a mute and bereft woman charged with arson, pens the details for a doctor at the St. Joseph Hospital for the Insane. He doesn’t want to find her guilty and hopes she can save herself.

An atmosphere of dread is conjured up from her tale’s beginning as Elsie, a recent widow, travels by carriage to her late husband Rupert’s family home along with Rupert’s mousy cousin, Sarah. What greets them at the Jacobean manor called “The Bridge” is crumbling disrepair – and something more. The serving maids are untrained, the gardens unkempt, the rooms dusty, and she hears odd hissing sounds at night. The coffin with Rupert’s body awaits burial there, too, with small marks on his skin resembling splinters. Nobody in the nearby village of Fayford wants anything to do with the place, due to rumors of witchcraft and a centuries-old feud. It’s hardly the place for Elsie to raise the child she’s carrying.

Then, after picking the lock of the third-floor garret, she and Sarah discover the previous inhabitants’ dust-choked belongings, two volumes of a 17th-century diary, and a free-standing portrait of a girl, mounted on wood, who resembles both Elsie and Rupert. The presence of these figures, called “silent companions” and reportedly of Dutch origin, adds uniqueness to the classic gothic setting. (Between these figures and the elaborate dollhouse in Jessie Burton’s The Miniaturist, the Netherlands is clearly the place to look for creative 17th-century artisanship.)

Equally gripping is the account of Anne Bainbridge starting in 1635, just prior to the Civil War years, as she and her husband prepare for a royal visit. A couple of intriguing details (why does one "companion" look like Elsie?) could have been clarified further, but the mystery about the house’s malevolent presence has a darkly satisfying explanation.

As the suspense heightens, and Elsie and her household find themselves in grave danger, the tone moves from subtly creepy to outright gory – a bit too gory for me in places – and yet more horrors lie in the all-too-real depictions of women’s powerlessness.

The Silent Companions was published this month by Penguin ($16 US, $22 Canada); I read it from a NetGalley copy. Want to win a copy for yourself? Please fill out the form below to enter the giveaway (this copy was originally provided by the publisher). Void where prohibited, and one entry per household, please. Deadline next Friday, March 23. Good luck!

Loading...

Published on March 16, 2018 05:00

March 12, 2018

Book review: Harbor of Spies: A Novel of Historic Havana, by Robin Lloyd

Cuba’s capital, Havana, a neutral port during the U.S. Civil War, serves as a base for Confederate trade and plotting and corresponding Union espionage. In Lloyd’s (Rough Passage to London, 2013) exciting second novel, set in 1863, this Spanish-controlled city swarms with activity, from the shipping industry’s constant din to the masquerade dances that serve as an apt metaphor for individuals’ covert motives.

Cuba’s capital, Havana, a neutral port during the U.S. Civil War, serves as a base for Confederate trade and plotting and corresponding Union espionage. In Lloyd’s (Rough Passage to London, 2013) exciting second novel, set in 1863, this Spanish-controlled city swarms with activity, from the shipping industry’s constant din to the masquerade dances that serve as an apt metaphor for individuals’ covert motives.Everett Townsend, a 19-year-old American schooner captain, gets drawn into danger after rescuing an escaped English prisoner. Blackmailed by a Spanish merchant into smuggling cargo through the Union blockade of the South, Townsend gathers a crew and follows his assignment while pondering his moral quandary.

The shipboard action is exhilarating, and intrigue beckons on land, too, with intertwining subplots about a British diplomat’s unresolved murder, a mystery involving Townsend’s late Cuban mother, and his growing affections for an innkeeper’s daughter. The story eventually leads him straight into the dark, cruel heart of the Cuban economy.

This is an involving reading experience for maritime fans and landlubbers alike. One hopes Townsend’s adventures will continue in future books.

Harbor of Spies was published on March 1st by Lyons Press, and this review was written for Booklist's Feb 15th issue.

Some other notes:

- I have to give credit to novels that defy my expectations. Although nautical adventure novels aren't my preferred subgenre, Harbor of Spies is much more than that, as I hope the review indicates. Plus, the action sequences on board ship were genuinely exciting and didn't get bogged down in jargon.

- The British diplomat in question is George Backhouse, a historical figure who was posted to Cuba and mysteriously murdered in 1855.

- The author, Robin Lloyd, was a longtime correspondent for NBC News who grew up "sailing in the Caribbean" (per his online bio).

- For Civil War fiction fans, this novel offers a less familiar perspective on events, which I appreciated. I've been reviewing many novels set in and around this period lately, including Charles Frazier's Varina, and I'll be posting my thoughts closer to that book's publication date.

Published on March 12, 2018 05:00

March 8, 2018

A dozen new and upcoming historical novels with intriguing cover art

This post is dedicated to historical fiction cover art, one of my favorite subjects, and one I haven't posted about recently. Twelve intriguing covers for new and forthcoming historical novels are below. Will you be adding any of these to your TBRs, or have you read them already?

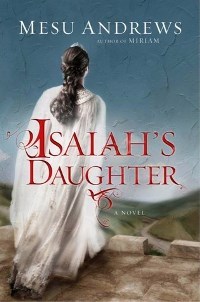

Andrews' latest biblical fiction novel has a striking color combination in its design: the blue turning into an almost grey, and the title in a deep red font. The title character's pose is classic (a woman facing away from the reader), but the rest makes it stand out. WaterBrook, Jan 2018. [see on Goodreads]

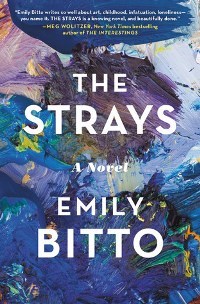

The creative cover for The Strays (from Australian novelist Bitto) seems perfect for a novel about artists and bohemian types in Depression-era Melbourne. Twelve, Jan 2018. [see on Goodreads]

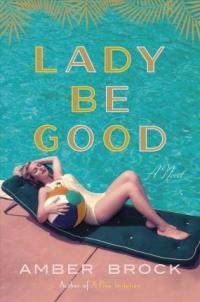

This novel set among socialites in 1950s America and Havana looks like a decadent read perfect for summertime. Crown, June 2018. [see on Goodreads]

And moving on to something completely different. A dramatic color combo for Cornwell's new Elizabethan-set novel (this is the UK paperback). It looks respectably historical, and the foregrounded red promises action and turmoil. HarperCollins UK, April 2018. [see on Goodreads]

I chose this one because the setting calls to mind the coastal setting for Poldark, and Costeloe's latest is set in nineteenth-century Cornwall, but some decades afterward. Head of Zeus, May 2018. [see on Goodreads]

I love this evocative portrait of London at twilight - the color of the Thames and the sky above, and check out the little dog in the lower right corner of the image. It makes for an eye-catching Victorian mystery. Minotaur, Feb 2018. [see on Goodreads]

Ann Mah's newest novel takes place in wine country - the French region of Burgundy - in WWII and the present day. The cover design echoes the locale and appears warm, inviting, and earthy. Morrow, June 2018. [see on Goodreads]

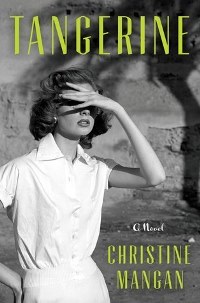

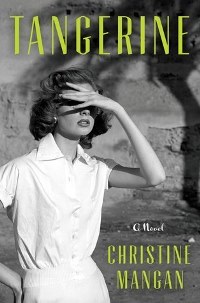

Such an edgy cover for Christine Mangan's debut novel set in '50s Morocco: the black and white palette (except the title and author), the dark shadows, the woman's expression and pose, the unusual way her fingers are splayed... it reminds me of a Hitchcock film. Ecco, May 2018. [see on Goodreads]

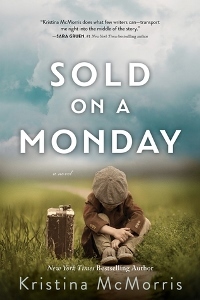

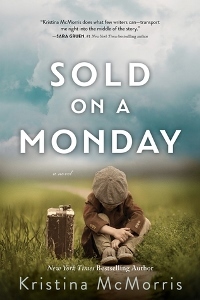

The cover for Sold on a Monday tells a story, one that will undoubtedly be heartbreaking in parts, but it's one I want to read in hopes that all will turn out well. Not surprisingly, it takes place during the Depression years. Sourcebooks, Sept 2018. [see on Goodreads]

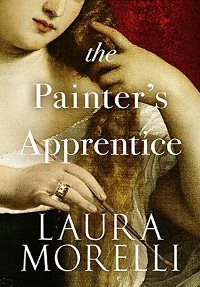

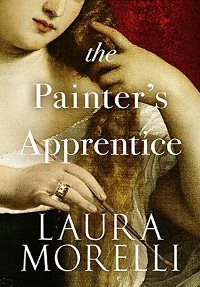

You don't see many historical novel covers based on historical portraits any more, which is unfortunate. This is a classic example of one used for a novel set in Renaissance-era Venice, and it works very well. The Scriptorium, Nov 2017. [see on Goodreads]

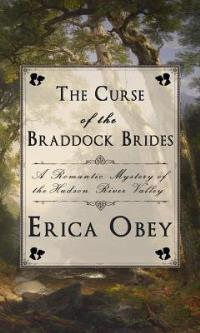

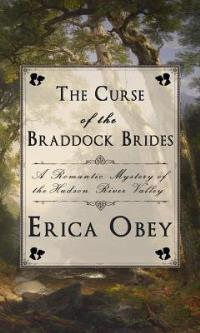

I'm always willing to be won over by an attractive historical-looking font. The subtitle says "a romantic mystery of the Hudson River Valley," and both the woodsy backdrop and the title placard evoke the setting and era (late 19th century). Walrus, Apr 2017. [see on Goodreads]

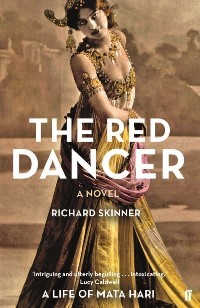

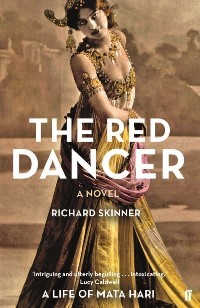

The sepia photograph on the cover (colorized a bit) is one that makes me want to find out more about its subject, Margaretha Zelle, better known as Mata Hari. This is a recent reissue of Skinner's novel, first published in 2001. Faber & Faber, 2017. [see on Goodreads]

Andrews' latest biblical fiction novel has a striking color combination in its design: the blue turning into an almost grey, and the title in a deep red font. The title character's pose is classic (a woman facing away from the reader), but the rest makes it stand out. WaterBrook, Jan 2018. [see on Goodreads]

The creative cover for The Strays (from Australian novelist Bitto) seems perfect for a novel about artists and bohemian types in Depression-era Melbourne. Twelve, Jan 2018. [see on Goodreads]

This novel set among socialites in 1950s America and Havana looks like a decadent read perfect for summertime. Crown, June 2018. [see on Goodreads]

And moving on to something completely different. A dramatic color combo for Cornwell's new Elizabethan-set novel (this is the UK paperback). It looks respectably historical, and the foregrounded red promises action and turmoil. HarperCollins UK, April 2018. [see on Goodreads]

I chose this one because the setting calls to mind the coastal setting for Poldark, and Costeloe's latest is set in nineteenth-century Cornwall, but some decades afterward. Head of Zeus, May 2018. [see on Goodreads]

I love this evocative portrait of London at twilight - the color of the Thames and the sky above, and check out the little dog in the lower right corner of the image. It makes for an eye-catching Victorian mystery. Minotaur, Feb 2018. [see on Goodreads]

Ann Mah's newest novel takes place in wine country - the French region of Burgundy - in WWII and the present day. The cover design echoes the locale and appears warm, inviting, and earthy. Morrow, June 2018. [see on Goodreads]

Such an edgy cover for Christine Mangan's debut novel set in '50s Morocco: the black and white palette (except the title and author), the dark shadows, the woman's expression and pose, the unusual way her fingers are splayed... it reminds me of a Hitchcock film. Ecco, May 2018. [see on Goodreads]

The cover for Sold on a Monday tells a story, one that will undoubtedly be heartbreaking in parts, but it's one I want to read in hopes that all will turn out well. Not surprisingly, it takes place during the Depression years. Sourcebooks, Sept 2018. [see on Goodreads]

You don't see many historical novel covers based on historical portraits any more, which is unfortunate. This is a classic example of one used for a novel set in Renaissance-era Venice, and it works very well. The Scriptorium, Nov 2017. [see on Goodreads]

I'm always willing to be won over by an attractive historical-looking font. The subtitle says "a romantic mystery of the Hudson River Valley," and both the woodsy backdrop and the title placard evoke the setting and era (late 19th century). Walrus, Apr 2017. [see on Goodreads]

The sepia photograph on the cover (colorized a bit) is one that makes me want to find out more about its subject, Margaretha Zelle, better known as Mata Hari. This is a recent reissue of Skinner's novel, first published in 2001. Faber & Faber, 2017. [see on Goodreads]

Published on March 08, 2018 04:00