Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 60

June 7, 2018

Adventures in flight: Chasing the Wind by C.C. Humphreys

Like its go-getter heroine, C. C. Humphreys’ newest historical thriller starts on the ground but quickly takes off. Pilot Roxy Loewen, fleeing from her father’s creditors and the man responsible for his death on a New York street in 1929, makes a grand exit from the scene – with some help from fellow aviator Amelia Earhart.

Like its go-getter heroine, C. C. Humphreys’ newest historical thriller starts on the ground but quickly takes off. Pilot Roxy Loewen, fleeing from her father’s creditors and the man responsible for his death on a New York street in 1929, makes a grand exit from the scene – with some help from fellow aviator Amelia Earhart. Seven years later, she’s running guns into British Somaliland alongside her German commie lover, Jocco Zomack, doing her part to support the Ethiopians’ war against the Italians. But even as Mussolini claims victory, there’s another battle right behind it. Roxy’s next mission: fly more guns into politically torn Madrid, pick up an original Bruegel painting, lift it out of the country, and deliver it to a buyer in Berlin, on behalf of Jocco’s art dealer father – all without Hermann Göring and his goons finding out.

A bold feat, but Roxy’s sure she can do it. The money’s good, too. But she hasn’t counted on the Nazis partnering with her arch-nemesis.

With Chasing the Wind, Humphreys, who has made many forays into 16th through 18th-century settings, successfully vaults ahead to the first decades of the 20th century, when the world was reacting to the stock market crash, eruptions into civil war, and the rising tide of fascism.

With Chasing the Wind, Humphreys, who has made many forays into 16th through 18th-century settings, successfully vaults ahead to the first decades of the 20th century, when the world was reacting to the stock market crash, eruptions into civil war, and the rising tide of fascism.He shows that he's mastered the skill of combining fast-paced action with vibrant historical detail. As the story speeds along with Roxy’s daring schemes and hairsbreadth escapes, it also delves into the techniques of forging a centuries-old painting and flying a small aircraft. Readers also get to experience the tense atmosphere of the 1936 Berlin Olympics (“Sport and politics are not separate, not at all. This display is all about power,” Roxy aptly observes) and walk through the opulent interior landscapes of the Hindenburg on its final voyage.

Roxy’s a gal with moxie to spare, but she’s not superhuman; she often experiences setbacks. She’s tough but compassionate: as Jocco tells her, “I know you care more than you admit.” That sometimes gives her adversaries the advantage, but it also makes her a relatable, admirable character.

Granted, if you don’t take to wild adventures that just happen to swoop through some of the era’s most significant events, this may not be your book. But if you're tempted to try keeping up with Roxy, though, it's great fun; just hang on and enjoy the flight.

Chasing the Wind is published in Canada by Doubleday Canada, and in the US as an indie title (ebook). Thanks to Historical Fiction Virtual Book Tours for providing me with a Kindle copy.

Published on June 07, 2018 04:30

June 5, 2018

Past v. Present: The Challenges of a Historical Thriller. an essay by Terrence McCauley

In today's post, author Terrence McCauley, who writes novels set in the past and others in the present-day, describes the appeal and challenges of writing fiction set in 1930s NYC.

~

Past v. Present: The Challenges of a Historical Thriller Terrence McCauley

As a writer, I always look for new ways to challenge myself. I never want to keep writing the same story over and over again. I don’t think the audience want to read the same kind of story, either. That’s one of the many reasons why I love setting my stories in different time periods. For example, my University series (Sympathy for the Devil, A Murder of Crows, A Conspiracy of Ravens) are all modern day techno-thrillers with plenty of action and technology to help me keep the pace moving.

Historical fiction does not allow me that luxury. And I wouldn’t have it any other way. Writing about 1930s New York affords me another set of challenges I wholeheartedly embrace. My Charlie Doherty novels (The Devil Dogs of Belleau Wood, Slow Burn, and now The Fairfax Incident) are different from any other kind of story I tell. I write them in the first person from Charlie’s perspective because I want the reader to get a sense of what he’s experiencing as he’s experiencing it. I don’t give myself the ability to use the third person omniscient narrator because I’m afraid of getting too far ahead in the story. I have a reason for that.

Historical fiction does not allow me that luxury. And I wouldn’t have it any other way. Writing about 1930s New York affords me another set of challenges I wholeheartedly embrace. My Charlie Doherty novels (The Devil Dogs of Belleau Wood, Slow Burn, and now The Fairfax Incident) are different from any other kind of story I tell. I write them in the first person from Charlie’s perspective because I want the reader to get a sense of what he’s experiencing as he’s experiencing it. I don’t give myself the ability to use the third person omniscient narrator because I’m afraid of getting too far ahead in the story. I have a reason for that.

When writing about a bygone era, it’s very easy for the writer to slip into something I call the "dreaded data dump," an unfortunate place where the author is anxious to demonstrate how much research he or she did on the era by packing the story with historically accurate facts. These data dumps are usually long sections that might be interesting to read, but often kill the momentum of the story. By only allowing myself to use the first person voice, I can constantly yet subtly remind the reader of the time and setting of the novel. I can either talk about the grand mansions and packed streets of Old New York, or I can have Charlie mention them as he’s moving from one location to the other on his way to cracking the case. People tend to skip over passages that are too long, and that means death to a writer and a story.

My books may be set in the past, but they’re being read by a modern audience who have all of the distractions of the day. Emails, texts, social media are all at the reader’s fingertips, especially if they’re reading on a tablet or smartphone. The last thing I want them to do is leave Charlie’s world to glance at what’s happening right now.

Getting a modern reader to relate to the 1930s is also a challenge that must be overcome. Some pick up a book like mine expecting to read a hats-and-gats drama with tough private detectives, gun molls and wise-cracking gangsters. That’s why I try to make my characters more believable by showing the people of that era are very relatable to the people of today. Many of my characters are survivors. They’ve lived through the horrors of the First World War, the boozy glamour of the Roaring Twenties and are now suffering through the horrible hangover of the beginning stages of the Great Depression. Times are bad and promise to get worse. But rather than tell the reader all of that, I have chosen to relate that story from Charlie’s point of view. He’s as world-weary as the next guy, but he doesn’t fall into the same categories of similar characters who have come before him. He isn’t idealistic, he doesn’t follow a code and he’s not above shoving someone aside to grab a quick buck. He’s a product of his time; a former detective who had made plenty of money during the corrupt Tammany Hall era, but finds himself pushed aside by the Reform movement sweeping the day. I don’t tell the reader any of this. I show them through Charlie’s internal dialogue and actions. I find this makes it easier for the reader to understand the time by seeing it all through Charlie’s eyes.

author Terrence McCauleyAnother challenge about writing about the past is overcoming modern biases about the actions and opinions of characters from another age. For example, I didn’t include a female detective in Fairfax because, quite frankly, there weren’t many female detectives back then. Sure, there were a few, but not enough to make one’s inclusion in my story seem realistic. Doing so would have been jarring and, as I said earlier, the last thing I want to do is pull the reader’s eyes off the page. That also doesn’t mean I make all the women in my books flappers or house fraus, either. Instead, the women in Fairfax and my other 1930s books are strong and influential in their own way. In Prohibition, for example, Alice may seem weak, but she exudes a lot of influence over the enforcer Terry Quinn. In Fairfax, I don’t think anyone would want to find themselves across the bargaining table from the formidable matriarch Mrs. Fairfax. And one of the main villains in the book doesn’t pick up a Tommy gun and begin firing. She is far more powerful by using her intelligence and cunning to serve her cause.

author Terrence McCauleyAnother challenge about writing about the past is overcoming modern biases about the actions and opinions of characters from another age. For example, I didn’t include a female detective in Fairfax because, quite frankly, there weren’t many female detectives back then. Sure, there were a few, but not enough to make one’s inclusion in my story seem realistic. Doing so would have been jarring and, as I said earlier, the last thing I want to do is pull the reader’s eyes off the page. That also doesn’t mean I make all the women in my books flappers or house fraus, either. Instead, the women in Fairfax and my other 1930s books are strong and influential in their own way. In Prohibition, for example, Alice may seem weak, but she exudes a lot of influence over the enforcer Terry Quinn. In Fairfax, I don’t think anyone would want to find themselves across the bargaining table from the formidable matriarch Mrs. Fairfax. And one of the main villains in the book doesn’t pick up a Tommy gun and begin firing. She is far more powerful by using her intelligence and cunning to serve her cause.

All of the devices and themes I mention here serve one purpose: to do everything I can to get the reader to buy in to the story. People read historical fiction for a lot of reasons. One reason I read it is to lose myself in a time that I might know something about, but wish to read about it in a fictionalized setting. My goal in writing Fairfax and my other 1930s novels is to introduce the reader to a time that’s not all unlike our own. A time where civil unrest and political paranoia runs rampant. A time when people worked hard and did what they had to do to survive. And to show them a protagonist who is far from a hero, but does the best he can with who he is.

The more things change, the more they seem to stay the same.

~

Terrence McCauley's The Fairfax Incident is published today by Polis Books.

~

Past v. Present: The Challenges of a Historical Thriller Terrence McCauley

As a writer, I always look for new ways to challenge myself. I never want to keep writing the same story over and over again. I don’t think the audience want to read the same kind of story, either. That’s one of the many reasons why I love setting my stories in different time periods. For example, my University series (Sympathy for the Devil, A Murder of Crows, A Conspiracy of Ravens) are all modern day techno-thrillers with plenty of action and technology to help me keep the pace moving.

Historical fiction does not allow me that luxury. And I wouldn’t have it any other way. Writing about 1930s New York affords me another set of challenges I wholeheartedly embrace. My Charlie Doherty novels (The Devil Dogs of Belleau Wood, Slow Burn, and now The Fairfax Incident) are different from any other kind of story I tell. I write them in the first person from Charlie’s perspective because I want the reader to get a sense of what he’s experiencing as he’s experiencing it. I don’t give myself the ability to use the third person omniscient narrator because I’m afraid of getting too far ahead in the story. I have a reason for that.

Historical fiction does not allow me that luxury. And I wouldn’t have it any other way. Writing about 1930s New York affords me another set of challenges I wholeheartedly embrace. My Charlie Doherty novels (The Devil Dogs of Belleau Wood, Slow Burn, and now The Fairfax Incident) are different from any other kind of story I tell. I write them in the first person from Charlie’s perspective because I want the reader to get a sense of what he’s experiencing as he’s experiencing it. I don’t give myself the ability to use the third person omniscient narrator because I’m afraid of getting too far ahead in the story. I have a reason for that.When writing about a bygone era, it’s very easy for the writer to slip into something I call the "dreaded data dump," an unfortunate place where the author is anxious to demonstrate how much research he or she did on the era by packing the story with historically accurate facts. These data dumps are usually long sections that might be interesting to read, but often kill the momentum of the story. By only allowing myself to use the first person voice, I can constantly yet subtly remind the reader of the time and setting of the novel. I can either talk about the grand mansions and packed streets of Old New York, or I can have Charlie mention them as he’s moving from one location to the other on his way to cracking the case. People tend to skip over passages that are too long, and that means death to a writer and a story.

My books may be set in the past, but they’re being read by a modern audience who have all of the distractions of the day. Emails, texts, social media are all at the reader’s fingertips, especially if they’re reading on a tablet or smartphone. The last thing I want them to do is leave Charlie’s world to glance at what’s happening right now.

Getting a modern reader to relate to the 1930s is also a challenge that must be overcome. Some pick up a book like mine expecting to read a hats-and-gats drama with tough private detectives, gun molls and wise-cracking gangsters. That’s why I try to make my characters more believable by showing the people of that era are very relatable to the people of today. Many of my characters are survivors. They’ve lived through the horrors of the First World War, the boozy glamour of the Roaring Twenties and are now suffering through the horrible hangover of the beginning stages of the Great Depression. Times are bad and promise to get worse. But rather than tell the reader all of that, I have chosen to relate that story from Charlie’s point of view. He’s as world-weary as the next guy, but he doesn’t fall into the same categories of similar characters who have come before him. He isn’t idealistic, he doesn’t follow a code and he’s not above shoving someone aside to grab a quick buck. He’s a product of his time; a former detective who had made plenty of money during the corrupt Tammany Hall era, but finds himself pushed aside by the Reform movement sweeping the day. I don’t tell the reader any of this. I show them through Charlie’s internal dialogue and actions. I find this makes it easier for the reader to understand the time by seeing it all through Charlie’s eyes.

author Terrence McCauleyAnother challenge about writing about the past is overcoming modern biases about the actions and opinions of characters from another age. For example, I didn’t include a female detective in Fairfax because, quite frankly, there weren’t many female detectives back then. Sure, there were a few, but not enough to make one’s inclusion in my story seem realistic. Doing so would have been jarring and, as I said earlier, the last thing I want to do is pull the reader’s eyes off the page. That also doesn’t mean I make all the women in my books flappers or house fraus, either. Instead, the women in Fairfax and my other 1930s books are strong and influential in their own way. In Prohibition, for example, Alice may seem weak, but she exudes a lot of influence over the enforcer Terry Quinn. In Fairfax, I don’t think anyone would want to find themselves across the bargaining table from the formidable matriarch Mrs. Fairfax. And one of the main villains in the book doesn’t pick up a Tommy gun and begin firing. She is far more powerful by using her intelligence and cunning to serve her cause.

author Terrence McCauleyAnother challenge about writing about the past is overcoming modern biases about the actions and opinions of characters from another age. For example, I didn’t include a female detective in Fairfax because, quite frankly, there weren’t many female detectives back then. Sure, there were a few, but not enough to make one’s inclusion in my story seem realistic. Doing so would have been jarring and, as I said earlier, the last thing I want to do is pull the reader’s eyes off the page. That also doesn’t mean I make all the women in my books flappers or house fraus, either. Instead, the women in Fairfax and my other 1930s books are strong and influential in their own way. In Prohibition, for example, Alice may seem weak, but she exudes a lot of influence over the enforcer Terry Quinn. In Fairfax, I don’t think anyone would want to find themselves across the bargaining table from the formidable matriarch Mrs. Fairfax. And one of the main villains in the book doesn’t pick up a Tommy gun and begin firing. She is far more powerful by using her intelligence and cunning to serve her cause. All of the devices and themes I mention here serve one purpose: to do everything I can to get the reader to buy in to the story. People read historical fiction for a lot of reasons. One reason I read it is to lose myself in a time that I might know something about, but wish to read about it in a fictionalized setting. My goal in writing Fairfax and my other 1930s novels is to introduce the reader to a time that’s not all unlike our own. A time where civil unrest and political paranoia runs rampant. A time when people worked hard and did what they had to do to survive. And to show them a protagonist who is far from a hero, but does the best he can with who he is.

The more things change, the more they seem to stay the same.

~

Terrence McCauley's The Fairfax Incident is published today by Polis Books.

Published on June 05, 2018 05:00

June 3, 2018

Katherine Kovacic's The Portrait of Molly Dean, a multi-period Australian thriller about a real-life unsolved murder

“Lane & Co. think they have a portrait of a pretty but unknown girl by an unknown artist. However, I am planning to buy a portrait by Colin Colahan of a girl who became famous for being the victim in one of Melbourne’s most sensational murders; a murder that has never been solved. Her name is Molly Dean.”

“Lane & Co. think they have a portrait of a pretty but unknown girl by an unknown artist. However, I am planning to buy a portrait by Colin Colahan of a girl who became famous for being the victim in one of Melbourne’s most sensational murders; a murder that has never been solved. Her name is Molly Dean.” These attention-grabbing sentences summarize the opening of Kovacic’s terrific new crime novel. In 1999, Alex Clayton, an art dealer used to turning paintings over swiftly for profit, arrives at an auction house knowing more about a portrait’s backstory than anyone—or so she thinks. After her successful bid, she researches its subject, uncovers a web of mysteries, and needs to know even more.

Molly Dean, the dark-haired, brown-eyed woman gazing out from the canvas, was the artist’s lover, a schoolteacher and aspiring writer with a troubled home life. In 1930, she was brutally beaten on a dark suburban lane and died hours later. The prime suspect went free, without even a trial. With the help of her art restorer friend John, the Mulder to her Scully, Alex investigates the decades-old mystery. An alternating thread follows Molly’s path up to that fateful night.

This is Kovacic’s debut, and thriller writing is clearly her forte. Her art-infused story has relentless pacing, and Alex’s brash attitude and witty voice exert a strong pull. Molly’s sections are slower and more detailed, and the bohemian world she inhabits is more implied than present, but her determination inspires respect. She seeks to escape her coarse, abusive mother and achieve her literary dreams but lacks sufficient support.

Molly was a real person, and her shocking biography is just as the author describes. Fans of Jessie Burton’s The Muse and Josephine Pennicott’s multi-period gothics should seek it out.

The Portrait of Molly Dean was published by Echo, an imprint of Bonnier Australia, this year. I hadn't heard of it until I came across it as a Read Now title on NetGalley, and it was a worthy find. US-based readers can find the e-version for sale at Amazon for $9.99. I reviewed it originally for May's Historical Novels Review. This is also my 3rd entry for this year's Australian Women Writers Challenge.

Published on June 03, 2018 08:00

May 31, 2018

Kevin Powers' A Shout in the Ruins, a literary novel of the Civil War and its long aftermath

Some passages in Powers’ second novel (after The Yellow Birds) unfold with a fable’s tragic inevitability, while its specificity of setting and character, both strikingly described and original, will brand them into the reader’s consciousness. In his depiction of America’s heritage of racial trauma, he takes the long view, moving between Civil War–era Virginia and 120-plus years later.

Some passages in Powers’ second novel (after The Yellow Birds) unfold with a fable’s tragic inevitability, while its specificity of setting and character, both strikingly described and original, will brand them into the reader’s consciousness. In his depiction of America’s heritage of racial trauma, he takes the long view, moving between Civil War–era Virginia and 120-plus years later.Mystery surrounds the fate of Emily Reid Levallois, mistress of the Beauvais Plantation, near Richmond, after a devastating 1866 fire. Scenes detail her unhappy circumstances: due to terrible battlefield injuries, her father is unable to prevent his covetous, cruel neighbor, Antony Levallois, from wedding Emily. An enslaved couple, Rawls and Nurse, are brought together and torn apart amid this atmosphere.

In a linked tale beginning in 1956, George Seldom, a ninety-something African American, travels through the segregated South to his onetime North Carolina home while pondering the unknown circumstances that ensured his childhood survival. Beautifully formed sentences express unsettling truths about humanity, yet tendrils of hope emerge via stories showing how love and kindness can take root in seemingly barren earth.

A Shout in the Ruins was published in May by Little, Brown; I wrote this review for Booklist's 4/15 issue. This is one among a number of recent books I was assigned on the topic of the Civil War and race relations, which seems to be a current trend in historical fiction.

Published on May 31, 2018 05:00

May 28, 2018

Swimming Between Worlds, Elaine Neil Orr's portrait of the Civil Rights era

Written with candor and compassion, Orr’s second novel takes place in the conservative South in 1959 with short flashbacks to her home country of Nigeria. Through the intertwining stories of Kate Monroe and Tacker Hart, she illustrates the challenges of unlearning ingrained racism and how immersion in a new culture can reveal problems in one’s own backyard.

Written with candor and compassion, Orr’s second novel takes place in the conservative South in 1959 with short flashbacks to her home country of Nigeria. Through the intertwining stories of Kate Monroe and Tacker Hart, she illustrates the challenges of unlearning ingrained racism and how immersion in a new culture can reveal problems in one’s own backyard. Both viewpoint characters sit at a crossroads. Tacker, a former high school football star, is back in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, pondering his career path. During the year and a half he spent in Ibadan on an architectural design project, he’d become good friends with his Nigerian coworkers and soaked up the Yoruba culture. Following his dramatic firing for “going native,” he takes a job at home, managing his father’s grocery. Kate, his former classmate, finds herself alone after her parents’ death. While debating a photography career, she learns a family secret that upends her world. After meeting Tacker again, she finds him attractive yet somehow changed, and he’s drawn to the prickly Kate.

The third protagonist is Gaines Townson, a young black man who Tacker hires and befriends, and of whom Kate is initially suspicious due to his skin color. Through Gaines, Tacker gets introduced to the ongoing civil rights struggle. This is the era of sit-ins at Woolworth lunch counters, segregated swimming pools, sexist attitudes, and racist attacks on African-Americans—all sharply rendered (and some of which sadly hasn’t changed). Fortunately, Gaines is more than a vehicle for the others’ emotional growth; he’s a well-developed character with a rich family life and his own future plans.

Against this backdrop of social unrest, their relationships with one another unfold in a tentative, realistic manner, as each decides what’s most important. Orr’s gracefully written, character-centered tale, showing how beliefs are formed and transformed, is both original and memorable.

Swimming Between Worlds was published by Berkley in April. I wrote this review for May's Historical Novels Review, based on a NetGalley copy. Elaine Neil Orr had contributed a guest post about her on-site research in Nigeria and North Carolina to the blog last month.

Published on May 28, 2018 04:30

May 24, 2018

Russia in Historical Fiction: A Journey of Sorrow and Strength, a guest post from Mary Anne Lewis

Today I have a guest essay by a fellow blogger, Mary Anne Lewis of Magic of History, which is a terrific new site focusing on reviews of historical fiction and history in books and on screen. There are a few novels mentioned below which were new to me, and I hope you'll find some worth adding to your own TBRs, too.

~

Russia in Historical Fiction: A Journey of Sorrow and StrengthMary Anne Lewis

From the icy winter steppe to the towering palaces in St. Petersburg, Russia never fails to enchant as the setting for a historical novel. While there are many novels from numerous eras set in Russia, it generally isn’t considered as popular as, say, books set in the Tudor era, or the first half of the twentieth century. Perhaps it’s the fact that Russia has such a repressive, bloody history, or that the Russian people tend toward a dark temperament because of all they’ve endured. Or, perhaps, it’s the lack of novels emanating from Russia since the Soviets took over in 1917.

For all of these reasons, the novelists who tackle Russia are a brave lot. It’s a huge country that’s hard to get to. Traveling the land has never been easy. The language is difficult. And, few nations have experienced the political machinations and bloody regime changes that Russia has. It’s difficult to keep the history straight, partially because there’s so much of it, and so much of it is so hard to believe.

For all of these reasons, the novelists who tackle Russia are a brave lot. It’s a huge country that’s hard to get to. Traveling the land has never been easy. The language is difficult. And, few nations have experienced the political machinations and bloody regime changes that Russia has. It’s difficult to keep the history straight, partially because there’s so much of it, and so much of it is so hard to believe.

Even readers need courage to consume Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Their books aren’t necessarily difficult, but they are sometimes hard to finish. Current day authors have also written about Russia, from the time of Ivan the Terrible to Catherine the Great to the Romanovs to World War II.

If you want to experience Russia of the old days, begin with Anna Karenina. It’s a tragedy, but also a reflection of what happens when infidelity impacts a Russian marriage and family in the nineteenth century. It’s the story of a young woman, Anna, who decides to leave her husband for the infamous Count Vronsky. Anna Karenina is perhaps the best book to showcase the Russian personality, long before the tsar was deposed and the Soviets took over.

Some would like to go back even further, to the reign of Catherine the Great. Many excellent non-fiction books deal with this topic, such as Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman by Robert K. Massie. One novel that stands out is The Winter Palace, a novel of Catherine the Great by Eva Stachniak. It’s written from the perspective of Varvara, a serving girl who becomes a spy in the Winter Palace. She’s trusted by Catherine the Great, but the two can’t truly be said to be friends. Catherine’s life contains so many highs and lows that a book about her can’t help but be exciting.

Some would like to go back even further, to the reign of Catherine the Great. Many excellent non-fiction books deal with this topic, such as Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman by Robert K. Massie. One novel that stands out is The Winter Palace, a novel of Catherine the Great by Eva Stachniak. It’s written from the perspective of Varvara, a serving girl who becomes a spy in the Winter Palace. She’s trusted by Catherine the Great, but the two can’t truly be said to be friends. Catherine’s life contains so many highs and lows that a book about her can’t help but be exciting.

Another book that takes place approximately at the same time is Push Not the River, by James Conroyd Martin. It’s the beginning of a trilogy about the wars fought for Polish independence in the latter part of the eighteenth century. Much of the book takes place in Poland, which was part of Russia on and off for many years. The book is supposedly based on a young girl’s diary from the period. Filled with scandals, the book has a soap opera quality about it, but when I wrote a review on Amazon and said that, the author responded to note all of it was in the diary. But books two and three come from his own imagination.

Now to move forward to the end of the Romanov dynasty. Again, numerous books have been written to detail this period. Most people interested in history know about the assassination of the tsar and the tsarina, their four daughters and their hemophiliac son. All their remains have been recovered, and DNA tests show that indeed, all seven were in two graves.

Now to move forward to the end of the Romanov dynasty. Again, numerous books have been written to detail this period. Most people interested in history know about the assassination of the tsar and the tsarina, their four daughters and their hemophiliac son. All their remains have been recovered, and DNA tests show that indeed, all seven were in two graves.

A couple of books I’ll mention aren’t necessarily among the best books about the tragedy, but I enjoyed them. The first is The Passion of Marie Romanov. Written by a Russian, Laura Rose, it’s a rather preposterous story of how third daughter Marie loses her virginity the night before she is murdered. Again, it’s supposedly based on diaries and letters, this time from the Romanov family. Unlikely or not, it’s very readable and imaginative.

The second book, Anastasia, by Colin Falconer, is set in the 1920s, when rumors were rife that the youngest daughter of the tsar had survived the slaughter. This is another “light” book which can’t be taken seriously. It’s about a woman who claims to be Anastasia and how others try to discover the truth. Colin Falconer has written more than forty books about a variety of historical locales and has a big fan base.

Another book set in the immediate aftermath of the assassinations is White Road, A Russian Odyssey, 1919-1923, by Olga Ilyin. I loved it. Technically, this isn’t fiction, but rather the story of a young woman caught up in the Bolshevik Revolution, written more than sixty years after the fact. The woman who wrote it lived it. She describes how she fled through Siberia in the midst of a Russian winter with her infant son, all because her husband was an officer in the White Army, which lost to Lenin and the Bolsheviks. She was a member of the gentry, and her book is filled with inspiration and hope. She also details her grief at Russia losing its great artists: its authors and musicians after the revolution, something I had never considered before.

Another book set in the immediate aftermath of the assassinations is White Road, A Russian Odyssey, 1919-1923, by Olga Ilyin. I loved it. Technically, this isn’t fiction, but rather the story of a young woman caught up in the Bolshevik Revolution, written more than sixty years after the fact. The woman who wrote it lived it. She describes how she fled through Siberia in the midst of a Russian winter with her infant son, all because her husband was an officer in the White Army, which lost to Lenin and the Bolsheviks. She was a member of the gentry, and her book is filled with inspiration and hope. She also details her grief at Russia losing its great artists: its authors and musicians after the revolution, something I had never considered before.

Moving forward to World War II, I’ll recommend a book that’s part of a great series by the recently deceased author Philip Kerr. It’s A Man Without Breath, about intrepid German detective Bernie Gunther. While he isn’t a Nazi, he is sent to Russia in 1943 to investigate the murder of Polish troops, and manages to escape certain death in a labor camp. While most of the series is set in Germany, this book shows that the Nazis weren’t the only cruel ones in the conflict.

I’ll mention one more book in a more modern setting. It’s Stalina, by Emily Rubin, the story of a Russian woman who travels to the United States after the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. While she wants a new life, she’s conflicted. She used to be a chemist in her homeland, but now she’s working in a seedy hotel. Again, it’s a great portrait of a Russian character.

I’ll mention one more book in a more modern setting. It’s Stalina, by Emily Rubin, the story of a Russian woman who travels to the United States after the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. While she wants a new life, she’s conflicted. She used to be a chemist in her homeland, but now she’s working in a seedy hotel. Again, it’s a great portrait of a Russian character.

All these books are dark, at least a little. But they open a vista into a mysterious land and the people who have called it home.

~

Mary Anne Lewis is a former journalist, a historical fiction fan, and the blog mistress of http://magicofhistory.com. Once, long ago, she worked in a library.

~

Russia in Historical Fiction: A Journey of Sorrow and StrengthMary Anne Lewis

From the icy winter steppe to the towering palaces in St. Petersburg, Russia never fails to enchant as the setting for a historical novel. While there are many novels from numerous eras set in Russia, it generally isn’t considered as popular as, say, books set in the Tudor era, or the first half of the twentieth century. Perhaps it’s the fact that Russia has such a repressive, bloody history, or that the Russian people tend toward a dark temperament because of all they’ve endured. Or, perhaps, it’s the lack of novels emanating from Russia since the Soviets took over in 1917.

For all of these reasons, the novelists who tackle Russia are a brave lot. It’s a huge country that’s hard to get to. Traveling the land has never been easy. The language is difficult. And, few nations have experienced the political machinations and bloody regime changes that Russia has. It’s difficult to keep the history straight, partially because there’s so much of it, and so much of it is so hard to believe.

For all of these reasons, the novelists who tackle Russia are a brave lot. It’s a huge country that’s hard to get to. Traveling the land has never been easy. The language is difficult. And, few nations have experienced the political machinations and bloody regime changes that Russia has. It’s difficult to keep the history straight, partially because there’s so much of it, and so much of it is so hard to believe. Even readers need courage to consume Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Their books aren’t necessarily difficult, but they are sometimes hard to finish. Current day authors have also written about Russia, from the time of Ivan the Terrible to Catherine the Great to the Romanovs to World War II.

If you want to experience Russia of the old days, begin with Anna Karenina. It’s a tragedy, but also a reflection of what happens when infidelity impacts a Russian marriage and family in the nineteenth century. It’s the story of a young woman, Anna, who decides to leave her husband for the infamous Count Vronsky. Anna Karenina is perhaps the best book to showcase the Russian personality, long before the tsar was deposed and the Soviets took over.

Some would like to go back even further, to the reign of Catherine the Great. Many excellent non-fiction books deal with this topic, such as Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman by Robert K. Massie. One novel that stands out is The Winter Palace, a novel of Catherine the Great by Eva Stachniak. It’s written from the perspective of Varvara, a serving girl who becomes a spy in the Winter Palace. She’s trusted by Catherine the Great, but the two can’t truly be said to be friends. Catherine’s life contains so many highs and lows that a book about her can’t help but be exciting.

Some would like to go back even further, to the reign of Catherine the Great. Many excellent non-fiction books deal with this topic, such as Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman by Robert K. Massie. One novel that stands out is The Winter Palace, a novel of Catherine the Great by Eva Stachniak. It’s written from the perspective of Varvara, a serving girl who becomes a spy in the Winter Palace. She’s trusted by Catherine the Great, but the two can’t truly be said to be friends. Catherine’s life contains so many highs and lows that a book about her can’t help but be exciting. Another book that takes place approximately at the same time is Push Not the River, by James Conroyd Martin. It’s the beginning of a trilogy about the wars fought for Polish independence in the latter part of the eighteenth century. Much of the book takes place in Poland, which was part of Russia on and off for many years. The book is supposedly based on a young girl’s diary from the period. Filled with scandals, the book has a soap opera quality about it, but when I wrote a review on Amazon and said that, the author responded to note all of it was in the diary. But books two and three come from his own imagination.

Now to move forward to the end of the Romanov dynasty. Again, numerous books have been written to detail this period. Most people interested in history know about the assassination of the tsar and the tsarina, their four daughters and their hemophiliac son. All their remains have been recovered, and DNA tests show that indeed, all seven were in two graves.

Now to move forward to the end of the Romanov dynasty. Again, numerous books have been written to detail this period. Most people interested in history know about the assassination of the tsar and the tsarina, their four daughters and their hemophiliac son. All their remains have been recovered, and DNA tests show that indeed, all seven were in two graves. A couple of books I’ll mention aren’t necessarily among the best books about the tragedy, but I enjoyed them. The first is The Passion of Marie Romanov. Written by a Russian, Laura Rose, it’s a rather preposterous story of how third daughter Marie loses her virginity the night before she is murdered. Again, it’s supposedly based on diaries and letters, this time from the Romanov family. Unlikely or not, it’s very readable and imaginative.

The second book, Anastasia, by Colin Falconer, is set in the 1920s, when rumors were rife that the youngest daughter of the tsar had survived the slaughter. This is another “light” book which can’t be taken seriously. It’s about a woman who claims to be Anastasia and how others try to discover the truth. Colin Falconer has written more than forty books about a variety of historical locales and has a big fan base.

Another book set in the immediate aftermath of the assassinations is White Road, A Russian Odyssey, 1919-1923, by Olga Ilyin. I loved it. Technically, this isn’t fiction, but rather the story of a young woman caught up in the Bolshevik Revolution, written more than sixty years after the fact. The woman who wrote it lived it. She describes how she fled through Siberia in the midst of a Russian winter with her infant son, all because her husband was an officer in the White Army, which lost to Lenin and the Bolsheviks. She was a member of the gentry, and her book is filled with inspiration and hope. She also details her grief at Russia losing its great artists: its authors and musicians after the revolution, something I had never considered before.

Another book set in the immediate aftermath of the assassinations is White Road, A Russian Odyssey, 1919-1923, by Olga Ilyin. I loved it. Technically, this isn’t fiction, but rather the story of a young woman caught up in the Bolshevik Revolution, written more than sixty years after the fact. The woman who wrote it lived it. She describes how she fled through Siberia in the midst of a Russian winter with her infant son, all because her husband was an officer in the White Army, which lost to Lenin and the Bolsheviks. She was a member of the gentry, and her book is filled with inspiration and hope. She also details her grief at Russia losing its great artists: its authors and musicians after the revolution, something I had never considered before. Moving forward to World War II, I’ll recommend a book that’s part of a great series by the recently deceased author Philip Kerr. It’s A Man Without Breath, about intrepid German detective Bernie Gunther. While he isn’t a Nazi, he is sent to Russia in 1943 to investigate the murder of Polish troops, and manages to escape certain death in a labor camp. While most of the series is set in Germany, this book shows that the Nazis weren’t the only cruel ones in the conflict.

I’ll mention one more book in a more modern setting. It’s Stalina, by Emily Rubin, the story of a Russian woman who travels to the United States after the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. While she wants a new life, she’s conflicted. She used to be a chemist in her homeland, but now she’s working in a seedy hotel. Again, it’s a great portrait of a Russian character.

I’ll mention one more book in a more modern setting. It’s Stalina, by Emily Rubin, the story of a Russian woman who travels to the United States after the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. While she wants a new life, she’s conflicted. She used to be a chemist in her homeland, but now she’s working in a seedy hotel. Again, it’s a great portrait of a Russian character.All these books are dark, at least a little. But they open a vista into a mysterious land and the people who have called it home.

~

Mary Anne Lewis is a former journalist, a historical fiction fan, and the blog mistress of http://magicofhistory.com. Once, long ago, she worked in a library.

Published on May 24, 2018 04:30

May 21, 2018

I Was Anastasia, a novel of identity, hope, and a long-enduring Romanov mystery

The mystery about the fate of Grand Duchess Anastasia, youngest daughter of Russia’s imperial family, has officially been resolved, but the subject still exerts fascination. Was she murdered alongside her parents and siblings after the Russian Revolution, or did she survive?

The mystery about the fate of Grand Duchess Anastasia, youngest daughter of Russia’s imperial family, has officially been resolved, but the subject still exerts fascination. Was she murdered alongside her parents and siblings after the Russian Revolution, or did she survive?Incorporating themes of identity and hope, Lawhon’s novel intertwines two strands: one following Anastasia up to that horrific night in 1918 and another about Anna Anderson, whose unwavering claims to be Anastasia inspired and confounded her contemporaries. Anastasia’s story, evoking her youthful spirit, becomes increasingly tense as her world grows dangerously constrained, while Anna’s story unfolds in snapshots flipping backward in time from 1970.

The suspense hinges on the reader’s unfamiliarity with the real history, and John Boyne’s The House of Special Purpose (2013), also about Anastasia, handles the dual-chronology structure more smoothly. However, Anna’s narrative, involving institutionalizations, glamorous excursions, legal battles, and meetings with people who want to support, exploit, or debunk her, compels with its many contrasts.

Recommended mainly for readers unacquainted with this twentieth-century mystery or anyone interested in Anna Anderson’s troubled life.

This short review first appeared in Booklist's February 1 issue, and the novel (which I read last November as an ARC) was published by Doubleday in March. Some additional notes:

- For my review of The House of Special Purpose, see my post Russian History, a Mystery, and a Reviewer's Dilemma, from 2013. My sentiments remain, and from that you may understand my thoughts about the chronological structure of I Was Anastasia (I'm not revealing anything about the conclusions drawn in either one, though). The structure also resembles that in the film Memento, which the author cites. I haven't seen the movie but may have to now!

- There's a lengthy author's note at the end that says "spoilers abound below" and goes on to explain and reveal various things, as author's notes do. It addresses potential readers, assuming they won't know the real history. I was surprised by this (the revelations about Anastasia were fairly big news when they appeared). Given that, I found it odd that knowledge of Grand Duchess Anastasia's fate was a hindrance to appreciating the book in full.

- I've read other reviews since I submitted mine, and it's been very well received by many readers who hadn't known Anastasia's story beforehand, and some who did. So I'll leave it to you to read it and make up your own mind about it.

Published on May 21, 2018 06:00

May 18, 2018

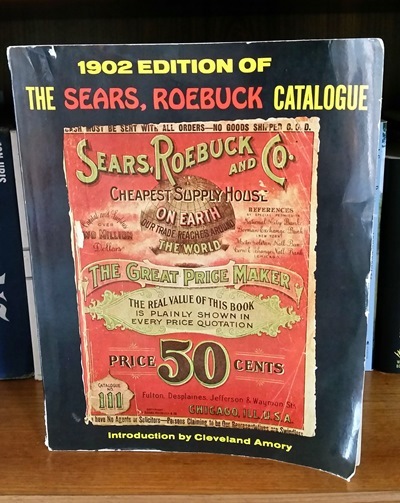

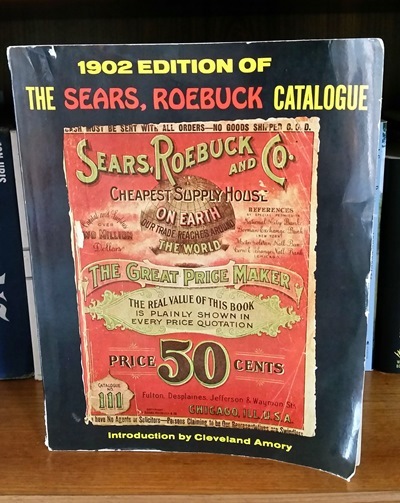

“THE REAL VALUE OF THIS BOOK”: How the Sears Catalogue Shaped My Novel, a guest post by Ellen Notbohm

Over the years, I've referred many library patrons to the Sears catalog replicas in our reference collection for insight into daily life in the early 20th century. And so I was pleased when Ellen Notbohm proposed to write a post detailing how she'd used one of these catalogs in the research process for her debut historical novel, The River by Starlight, which is set in turn-of-the-century Montana and based on real-life events. Please read on for more, and welcome, Ellen!

~

“THE REAL VALUE OF THIS BOOK”:

How the Sears Catalogue Shaped My NovelEllen Notbohm

How much research is enough? Writers of historical fiction know the dilemma well. We fall in love with our characters and want to know them as intimately as we can. What did their environment look like, smell like, feel like? What did they eat, wear, have in their homes? What were the tools of their trade, how did they conduct business, spend leisure time, celebrate holidays, doctor themselves and their families?

Researching my historical novel The River by Starlight involved six cross-country trips. Close to 100 books and numerous notebooks bulging with documents and newspaper clippings cram a seven-foot bookcase in my office. But as delightful karma would have it, the book I consulted more than any other, the one I dog-eared with use, cost me all of $1.50.

I found the 1902 Sears Catalogue on a lonely back table at a used book sale. As much an anthropology lesson as any textbook, author Cleveland Amory called it “a view of the American scene at the turn of the century with an excitement and accuracy that would defy the most eminent historian.”

“THE REAL VALUE OF THIS BOOK IS PLAINLY SHOWN IN EVERY PRICE QUOTATION” blares the front cover. From the Sears catalogue I learned what everything from thimbles to pianos cost, what they looked like, how many choices there were. What men, women and children wore in every imaginable situation, what size range was available (“Fat men usually experience much difficulty getting a shirt in the right shape.”). How credit worked. How it all reflected the larger economic picture of the country.

Details from the catalogue colored my descriptions of home furnishings, tools and weapons, toiletries and potions. Stoves and washing machines, hay loaders and hobby horses, paint and fabric colors. I acquired some rusty artifacts of homestead life and was able to see what they looked originally.

I wrote a frisky scene giving an intimate look at the layers of societally-required undergarments my female lead, Annie, dares to forego on a sweltering summer day. There’s a charged scene wherein you can all but smell the “overpowering cloud of Le Muguet” enveloping the town’s queen busybody. A gorgeous tortoise shell hair comb becomes an heirloom and a pair of “ugly cloth-top lace-ups” leads to disaster. We see and feel the fabrics used in a prostitute’s costume, a child’s nightgown, a wedding quilt, a funeral shroud, the garish handkerchief of the queen snoop’s informant.

I wrote a frisky scene giving an intimate look at the layers of societally-required undergarments my female lead, Annie, dares to forego on a sweltering summer day. There’s a charged scene wherein you can all but smell the “overpowering cloud of Le Muguet” enveloping the town’s queen busybody. A gorgeous tortoise shell hair comb becomes an heirloom and a pair of “ugly cloth-top lace-ups” leads to disaster. We see and feel the fabrics used in a prostitute’s costume, a child’s nightgown, a wedding quilt, a funeral shroud, the garish handkerchief of the queen snoop’s informant.

It was exhilarating to slather on such details throughout the story. But how much is enough? Alas, much was lost to the delete button, “cool research,” as more than one editor called it, that didn’t move the story forward. An example: the reader knows Annie and her sister Jenny shared glasses of lemonade out on Jenny’s porch. But they don’t get to see the original version of the scene: Annie sticking a pinkie through a door screen (“handsomer than the cut shows”), opening Jenny’s refrigerator (nope, Sears didn’t call it an icebox) and pouring the lemonade into ruby-stained tumblers while Jenny finishes up her work with a white cedar dash butter churn (“peculiarly adapted for milk and butter purposes”) and puts the butter into brass-locked molds (“securing the utmost possible rigidity”).

But writing those kinds of details helped me experience the world in which my characters lived, and empathize with its beauties and challenges. Even when deleted, the details remained embedded in the story by virtue of how they influenced the thoughts, dialogue and deeds of the characters.

A battered old cast-off catalogue—$1.50. Creating a richly faceted portrait of another time—priceless.

~

Ellen Notbohm

Ellen Notbohm

(credit: Andie Petkus Photography)An internationally renowned author, Ellen Notbohm’s work has informed and delighted millions in more than twenty languages. Writing from her experiences raising children with autism and ADHD, her perennially popular Ten Things Every Child with Autism Wishes You Knew has been an autism bestseller since 2005. In addition to her four award-winning books on autism, Ellen’s articles, columns and posts on such diverse subjects as history, genealogy, baseball, writing, and community affairs have appeared in major publications and captured audiences on every continent. Her article collection for Ancestry magazine (2005 – 2010) related stories both poignant and uplifting gathered during extensive research for her long-awaited debut novel, The River by Starlight, published in May 2018. A lifelong resident of Oregon, Ellen is an avid genealogist, knitter, reader, beachcomber, and thrift store hound who has never knowingly walked by a used bookstore without going in and dropping coin.

~

“THE REAL VALUE OF THIS BOOK”:

How the Sears Catalogue Shaped My NovelEllen Notbohm

How much research is enough? Writers of historical fiction know the dilemma well. We fall in love with our characters and want to know them as intimately as we can. What did their environment look like, smell like, feel like? What did they eat, wear, have in their homes? What were the tools of their trade, how did they conduct business, spend leisure time, celebrate holidays, doctor themselves and their families?

Researching my historical novel The River by Starlight involved six cross-country trips. Close to 100 books and numerous notebooks bulging with documents and newspaper clippings cram a seven-foot bookcase in my office. But as delightful karma would have it, the book I consulted more than any other, the one I dog-eared with use, cost me all of $1.50.

I found the 1902 Sears Catalogue on a lonely back table at a used book sale. As much an anthropology lesson as any textbook, author Cleveland Amory called it “a view of the American scene at the turn of the century with an excitement and accuracy that would defy the most eminent historian.”

“THE REAL VALUE OF THIS BOOK IS PLAINLY SHOWN IN EVERY PRICE QUOTATION” blares the front cover. From the Sears catalogue I learned what everything from thimbles to pianos cost, what they looked like, how many choices there were. What men, women and children wore in every imaginable situation, what size range was available (“Fat men usually experience much difficulty getting a shirt in the right shape.”). How credit worked. How it all reflected the larger economic picture of the country.

Details from the catalogue colored my descriptions of home furnishings, tools and weapons, toiletries and potions. Stoves and washing machines, hay loaders and hobby horses, paint and fabric colors. I acquired some rusty artifacts of homestead life and was able to see what they looked originally.

I wrote a frisky scene giving an intimate look at the layers of societally-required undergarments my female lead, Annie, dares to forego on a sweltering summer day. There’s a charged scene wherein you can all but smell the “overpowering cloud of Le Muguet” enveloping the town’s queen busybody. A gorgeous tortoise shell hair comb becomes an heirloom and a pair of “ugly cloth-top lace-ups” leads to disaster. We see and feel the fabrics used in a prostitute’s costume, a child’s nightgown, a wedding quilt, a funeral shroud, the garish handkerchief of the queen snoop’s informant.

I wrote a frisky scene giving an intimate look at the layers of societally-required undergarments my female lead, Annie, dares to forego on a sweltering summer day. There’s a charged scene wherein you can all but smell the “overpowering cloud of Le Muguet” enveloping the town’s queen busybody. A gorgeous tortoise shell hair comb becomes an heirloom and a pair of “ugly cloth-top lace-ups” leads to disaster. We see and feel the fabrics used in a prostitute’s costume, a child’s nightgown, a wedding quilt, a funeral shroud, the garish handkerchief of the queen snoop’s informant. It was exhilarating to slather on such details throughout the story. But how much is enough? Alas, much was lost to the delete button, “cool research,” as more than one editor called it, that didn’t move the story forward. An example: the reader knows Annie and her sister Jenny shared glasses of lemonade out on Jenny’s porch. But they don’t get to see the original version of the scene: Annie sticking a pinkie through a door screen (“handsomer than the cut shows”), opening Jenny’s refrigerator (nope, Sears didn’t call it an icebox) and pouring the lemonade into ruby-stained tumblers while Jenny finishes up her work with a white cedar dash butter churn (“peculiarly adapted for milk and butter purposes”) and puts the butter into brass-locked molds (“securing the utmost possible rigidity”).

But writing those kinds of details helped me experience the world in which my characters lived, and empathize with its beauties and challenges. Even when deleted, the details remained embedded in the story by virtue of how they influenced the thoughts, dialogue and deeds of the characters.

A battered old cast-off catalogue—$1.50. Creating a richly faceted portrait of another time—priceless.

~

Ellen Notbohm

Ellen Notbohm(credit: Andie Petkus Photography)An internationally renowned author, Ellen Notbohm’s work has informed and delighted millions in more than twenty languages. Writing from her experiences raising children with autism and ADHD, her perennially popular Ten Things Every Child with Autism Wishes You Knew has been an autism bestseller since 2005. In addition to her four award-winning books on autism, Ellen’s articles, columns and posts on such diverse subjects as history, genealogy, baseball, writing, and community affairs have appeared in major publications and captured audiences on every continent. Her article collection for Ancestry magazine (2005 – 2010) related stories both poignant and uplifting gathered during extensive research for her long-awaited debut novel, The River by Starlight, published in May 2018. A lifelong resident of Oregon, Ellen is an avid genealogist, knitter, reader, beachcomber, and thrift store hound who has never knowingly walked by a used bookstore without going in and dropping coin.

Published on May 18, 2018 04:00

May 16, 2018

Ain't Misbehavin' by Jennifer Lamont Leo, a sweet 1920s-era love story

Dot Rodgers and Charlie Corrigan are sweethearts, though their personalities are very different. It’s 1928 in Chicago, and fun-loving Dot wants to live it up, donning a sparkling frock for a downtown New Year’s Eve party, where she’ll spend time with old friends, chat with the musicians, and maybe get a lead on a future singing gig.

Dot Rodgers and Charlie Corrigan are sweethearts, though their personalities are very different. It’s 1928 in Chicago, and fun-loving Dot wants to live it up, donning a sparkling frock for a downtown New Year’s Eve party, where she’ll spend time with old friends, chat with the musicians, and maybe get a lead on a future singing gig. Dot’s grateful for her job selling hats at Marshall Field’s – after her father kicked her out, she needs to make her own way in the world – but loves the thrill of performing for a crowd. Charlie, however, prefers cozy small-town life to glittery social gatherings, especially when they involve illegal liquor and loud people of questionable morals.

A war veteran and churchgoer who helps run a dry goods store, he’s quiet and conservative; he also senses the underlying discontent the partygoers try to hide. Plus, he has other plans for the evening that involve offering his girl a diamond ring. However, although they love one another, both grow convinced they don’t belong in each other’s world.

Leo confidently sets her spirited inspirational romance during Chicago’s exuberant Jazz Age. She brings a full complement of 1920s-era slang to her portrait of this dynamic era, when investments were soaring, the latest fancy roadsters had heaters, and the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre was shaking up local news. The story skips along while also tackling serious issues, like women’s need for independence and the importance of judging people on their own merits.

Dot’s experience of religion is colored by her estranged preacher father’s hypocrisy, but with the help of Dorothy L. Sayers (who wrote books about theology in addition to detective stories -- that was new to me), she gets a new perspective on her spiritual life. The novel’s faith-based elements are lightly interwoven into the plot.

Dot’s and Charlie’s love story endures many ups and downs, and they sometimes make decisions that feel too hasty, but both are good people at heart. Since this is a romance, a happy outcome is assured, and subplots involving Charlie’s old flame, Italian gangsters, and the lead-up to Black Friday add color and drama to this sweet tale.

Jennifer Lamont Leo's Ain't Misbehavin' was published by Smitten Historical Romance in March. Thanks to the author and Historical Fiction Virtual Book Tours for providing me with a review copy. There's also a tour-wide giveaway:

During the Blog Tour we will be giving away two signed copies and two eBooks of Ain’t Misbehavin’ AND an Ain’t Misbehavin’ Compact Mirror! To enter, please enter via the Gleam form below.

Giveaway Rules

– Giveaway ends at 11:59pm EST on May 18th. You must be 18 or older to enter.

– Giveaway is open to US & Canada residents only.

– Only one entry per household.

– All giveaway entrants agree to be honest and not cheat the systems; any suspect of fraud is decided upon by blog/site owner and the sponsor, and entrants may be disqualified at our discretion.

– Winner has 48 hours to claim prize or new winner is chosen.

Ain't Misbehavin'

Published on May 16, 2018 05:00

May 15, 2018

Immersive Research for Historical Fiction Writing, a guest post by Jacqueline Friedland, author of Trouble the Water

Today I'm welcoming Jacqueline Friedland, author of Trouble the Water (SparkPress, May), who's contributed an essay about researching the historical atmosphere of the pre-Civil War South.

~

Immersive Research for Historical Fiction WritingJacqueline Friedland

It’s difficult to be immune to the intrigue of the old South, the plantation lifestyle, the hoop skirts and debutante balls, unparalleled opulence juxtaposed with the astonishing horrors of American slavery. I struggle to digest the perversity of a government-sanctioned system of slavery, but I am utterly seduced by the heroics of those who refused to sit idly by, those who risked their own lives to fight for the freedom of others and that which they knew was right. I chose to write my first novel about the antebellum South in order to showcase the human compassion and bravery that was a bright light during this dark era, and I knew I would have to dive headfirst into the 1800s if I wanted to get it right.

It’s difficult to be immune to the intrigue of the old South, the plantation lifestyle, the hoop skirts and debutante balls, unparalleled opulence juxtaposed with the astonishing horrors of American slavery. I struggle to digest the perversity of a government-sanctioned system of slavery, but I am utterly seduced by the heroics of those who refused to sit idly by, those who risked their own lives to fight for the freedom of others and that which they knew was right. I chose to write my first novel about the antebellum South in order to showcase the human compassion and bravery that was a bright light during this dark era, and I knew I would have to dive headfirst into the 1800s if I wanted to get it right.

My foundation in the history of the American South was fair at the outset, as I had majored in United States Culture and Literature during college. I devised a plan to deepen my understanding of the time period through a form of immersion. As a lover of books, I did what I always do when I have questions: I began reading. I read every novel I could get my hands on that had a plot based in any Southern state in the years preceding the American Civil War, from Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind to Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad, and everything in between. Some of the most useful were Mudbound by Hillary Jordan, The Kitchen House by Kathleen Grissom, The Invention of Wings by Sue Monk Kidd, and Jubilee by Margaret Walker, to name just a few.

I read one novel after another after another, and then mentally synthesized all this fiction, which allowed me to develop a broader sense for the atmosphere of the antebellum South. Feeling that I had strengthened my foundation, I then moved onto drier non-fiction and primary sources about the specific issues on which I aimed to focus. I read many accounts documenting the Underground Railroad, the life of various abolitionists, and political strife over slavery. I also read first-hand slave narratives, including accounts of escapes and attempted escapes. I scoured books about William Lloyd Garrison and other notable abolitionists of the time. I particularly enjoyed All on Fire by Henry Mayer, which was not only informative, but immensely readable.

After this intense reading tour, I finally felt prepared to begin my novel, which takes place between the years 1842-1853 and delves into not only the horrors of slavery, but also heroic attempts to subvert the “peculiar institution”. Of course, additional questions arose as I wrote. How fast does a horse travel? How long does it take to cross the Atlantic by steamship? When did the steamship become a common mode of transportation anyway? For these questions, I can say thank goodness for local libraries and even google.

After this intense reading tour, I finally felt prepared to begin my novel, which takes place between the years 1842-1853 and delves into not only the horrors of slavery, but also heroic attempts to subvert the “peculiar institution”. Of course, additional questions arose as I wrote. How fast does a horse travel? How long does it take to cross the Atlantic by steamship? When did the steamship become a common mode of transportation anyway? For these questions, I can say thank goodness for local libraries and even google.

Perhaps the most useful part of my research was the professor in my writing program who understood my tendency to get lost in details, to become thoroughly engrossed in interesting tidbits about the time period, even if those details had absolutely nothing to do with my book. This professor said to me, knowing the years I had already devoted to learning my era, “Stop it. Enough. Just write your story already.” So I did.

~

Jacqueline Friedland holds a BA from the University of Pennsylvania and a JD from NYU Law School. She practiced as an attorney in New York before returning to school to receive her MFA from Sarah Lawrence College. She lives in New York with her husband, four children, and a tiny dog. Trouble the Water is her first novel. (author photo credit: Rebecca Weiss Photography.)

~

Immersive Research for Historical Fiction WritingJacqueline Friedland

It’s difficult to be immune to the intrigue of the old South, the plantation lifestyle, the hoop skirts and debutante balls, unparalleled opulence juxtaposed with the astonishing horrors of American slavery. I struggle to digest the perversity of a government-sanctioned system of slavery, but I am utterly seduced by the heroics of those who refused to sit idly by, those who risked their own lives to fight for the freedom of others and that which they knew was right. I chose to write my first novel about the antebellum South in order to showcase the human compassion and bravery that was a bright light during this dark era, and I knew I would have to dive headfirst into the 1800s if I wanted to get it right.

It’s difficult to be immune to the intrigue of the old South, the plantation lifestyle, the hoop skirts and debutante balls, unparalleled opulence juxtaposed with the astonishing horrors of American slavery. I struggle to digest the perversity of a government-sanctioned system of slavery, but I am utterly seduced by the heroics of those who refused to sit idly by, those who risked their own lives to fight for the freedom of others and that which they knew was right. I chose to write my first novel about the antebellum South in order to showcase the human compassion and bravery that was a bright light during this dark era, and I knew I would have to dive headfirst into the 1800s if I wanted to get it right.My foundation in the history of the American South was fair at the outset, as I had majored in United States Culture and Literature during college. I devised a plan to deepen my understanding of the time period through a form of immersion. As a lover of books, I did what I always do when I have questions: I began reading. I read every novel I could get my hands on that had a plot based in any Southern state in the years preceding the American Civil War, from Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind to Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad, and everything in between. Some of the most useful were Mudbound by Hillary Jordan, The Kitchen House by Kathleen Grissom, The Invention of Wings by Sue Monk Kidd, and Jubilee by Margaret Walker, to name just a few.

I read one novel after another after another, and then mentally synthesized all this fiction, which allowed me to develop a broader sense for the atmosphere of the antebellum South. Feeling that I had strengthened my foundation, I then moved onto drier non-fiction and primary sources about the specific issues on which I aimed to focus. I read many accounts documenting the Underground Railroad, the life of various abolitionists, and political strife over slavery. I also read first-hand slave narratives, including accounts of escapes and attempted escapes. I scoured books about William Lloyd Garrison and other notable abolitionists of the time. I particularly enjoyed All on Fire by Henry Mayer, which was not only informative, but immensely readable.

After this intense reading tour, I finally felt prepared to begin my novel, which takes place between the years 1842-1853 and delves into not only the horrors of slavery, but also heroic attempts to subvert the “peculiar institution”. Of course, additional questions arose as I wrote. How fast does a horse travel? How long does it take to cross the Atlantic by steamship? When did the steamship become a common mode of transportation anyway? For these questions, I can say thank goodness for local libraries and even google.

After this intense reading tour, I finally felt prepared to begin my novel, which takes place between the years 1842-1853 and delves into not only the horrors of slavery, but also heroic attempts to subvert the “peculiar institution”. Of course, additional questions arose as I wrote. How fast does a horse travel? How long does it take to cross the Atlantic by steamship? When did the steamship become a common mode of transportation anyway? For these questions, I can say thank goodness for local libraries and even google. Perhaps the most useful part of my research was the professor in my writing program who understood my tendency to get lost in details, to become thoroughly engrossed in interesting tidbits about the time period, even if those details had absolutely nothing to do with my book. This professor said to me, knowing the years I had already devoted to learning my era, “Stop it. Enough. Just write your story already.” So I did.

~

Jacqueline Friedland holds a BA from the University of Pennsylvania and a JD from NYU Law School. She practiced as an attorney in New York before returning to school to receive her MFA from Sarah Lawrence College. She lives in New York with her husband, four children, and a tiny dog. Trouble the Water is her first novel. (author photo credit: Rebecca Weiss Photography.)

Published on May 15, 2018 04:30