Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 58

September 3, 2018

Il Viaggio: What Inspired My Journey to Write Claire’s Last Secret, a guest post by Marty Ambrose

In today's guest post, Marty Ambrose writes about the background to her new historical mystery, which centers on the "haunted summer" of 1816 – when a group of young people gathered in a large villa by Lake Geneva, creativity was sparked, and considerable drama ensued. Read on for her account of the circumstances inspiring Claire's Last Secret.

~

Il Viaggio: What Inspired My Journey to Write Claire’s Last SecretMarty Ambrose

Byron once said, “I awoke to find myself famous.” – Truly, it is every writer’s dream to be thrust into a world of sudden, unfolding adoration for one’s work. But the inspiration for Claire’s Last Secret was more of a nightmare: I “awoke” during my summer teaching hiatus to find myself with a back injury that left me practically housebound on an island, in between writing projects, and feeling like the world was passing me by.

Even though my husband was my rock, I felt isolated. People get busy. Time moves on. But I was waiting, not sure what was going to happen next. I watched a lot of the History Channel. I texted friends. I binge watched Netflix (loved “Shetland”!). And I read. New books. Old books. Classic books. Whatever books. And, slowly, in spite of the future’s uncertainty, I came to appreciate that I had given the gift of stepping out of life for a while and could just let my imagination run free.

Much of my life, I’ve been a scholar of the Byron/Shelley circle and had a stack of unread books about them piling up in my home office. I happened to pick up Daisy Hay’s volume, The Young Romantics, and learned that she had found a fragment of Claire Clairmont’s (Mary Shelley’s stepsister) journal, saying that the famous Byron/Shelley summer of “free love” in 1816 had created a “perfect hell” for her. Of course, Claire wrote those words when she was almost eighty (something that I was surprised to learn), impoverished, and living in Florence, Italy, having outlived the two great poets and Mary by many decades. Intrigued, I wondered what it would feel like to outlive everyone who had been part of one’s youth. As the lone remaining figure of that famous quartet, she’d been left behind.

Much of my life, I’ve been a scholar of the Byron/Shelley circle and had a stack of unread books about them piling up in my home office. I happened to pick up Daisy Hay’s volume, The Young Romantics, and learned that she had found a fragment of Claire Clairmont’s (Mary Shelley’s stepsister) journal, saying that the famous Byron/Shelley summer of “free love” in 1816 had created a “perfect hell” for her. Of course, Claire wrote those words when she was almost eighty (something that I was surprised to learn), impoverished, and living in Florence, Italy, having outlived the two great poets and Mary by many decades. Intrigued, I wondered what it would feel like to outlive everyone who had been part of one’s youth. As the lone remaining figure of that famous quartet, she’d been left behind.

In that moment, I bonded with Claire and decided to tell her story with the “voice,” that had not been heard yet, but as a fictional memoir.

As I delved into Claire’s life, pieces came together in my thoughts: her illicit love for Byron, her roller-coaster relationship with Mary and Shelley, and her later years in Italy—and I knew I had to tell her story from two perspectives: the young, reckless Claire and the older-but-wiser Claire. We see her at two stages in her life: when she’s seventeen during the summer of 1816 and when she’s 75, living in Italy as an expatriate. This was quite a challenge for me as a writer because her “young” voice is very different from her “mature” voice; she’s an older and wiser woman in much of the book, but still so influenced by what happened to her in her younger days. Then, there was the mystery of her lost daughter with Byron. Her lovers. Her passion for life. It all coalesced into the kind of genre-bending novel that I’ve always wanted to create. Even with my background in the Romantics, I had to complete a lot more research on Claire, pouring over biographies and savoring her marvelously witty letters. She was a remarkable, but rather elusive person as the “almost famous” member of the group, and I found she inspired me with her independent spirit.

As I wrote the book, I healed after successful back surgery, wrote a grant, and had the amazing opportunity to travel to Geneva and Florence with my hubby to research the book. I awoke to find myself with a new life. Like Claire, I had the chance to see Europe with fresh eyes—in my case as an author moving in a new creative direction with my historical fiction. I saw Castle Chillon on Lake Geneva and walked in the steps of the greatness that passed there before me. I saw Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein manuscript (with Percy’s notes) at the Bodmer Museum. I wandered in the Boboli Gardens in Florence, Italy, and imagined Claire’s final years, looking back but still believing in the future.

What began as a challenging physical injury eventually became my own summer of “awakening” into an entirely new life that inspires me each day: every writer’s dream, indeed.

~

Marty Ambrose has been a writer most of her life, consumed with the world of literature whether teaching English at Florida Southwestern State College or creating her own fiction. Her writing career has spanned almost fifteen years, with eight published novels for Avalon Books, Kensington Books, Thomas & Mercer—and, now, Severn House.

Marty Ambrose has been a writer most of her life, consumed with the world of literature whether teaching English at Florida Southwestern State College or creating her own fiction. Her writing career has spanned almost fifteen years, with eight published novels for Avalon Books, Kensington Books, Thomas & Mercer—and, now, Severn House.

Two years ago, Marty had the opportunity to apply for a grant that took her to Geneva and Florence to research a new creative direction that builds on her interest in the Romantic poets: historical fiction. Her new book, Claire’s Last Secret, combines memoir and mystery in a genre-bending narrative of the Byron/Shelley “haunted summer,” with Claire Clairmont, as the protagonist/sleuth—the “almost famous” member of the group. The novel spans two eras played out against the backdrop of nineteenth-century Italy and is the first of a trilogy.

Marty lives on an island in Southwest Florida with her husband, former news-anchor, Jim McLaughlin. They are planning a three-week trip to Italy this fall to attend a book festival and research the second book, A Shadowed Fate.

~

Il Viaggio: What Inspired My Journey to Write Claire’s Last SecretMarty Ambrose

Byron once said, “I awoke to find myself famous.” – Truly, it is every writer’s dream to be thrust into a world of sudden, unfolding adoration for one’s work. But the inspiration for Claire’s Last Secret was more of a nightmare: I “awoke” during my summer teaching hiatus to find myself with a back injury that left me practically housebound on an island, in between writing projects, and feeling like the world was passing me by.

Even though my husband was my rock, I felt isolated. People get busy. Time moves on. But I was waiting, not sure what was going to happen next. I watched a lot of the History Channel. I texted friends. I binge watched Netflix (loved “Shetland”!). And I read. New books. Old books. Classic books. Whatever books. And, slowly, in spite of the future’s uncertainty, I came to appreciate that I had given the gift of stepping out of life for a while and could just let my imagination run free.

Much of my life, I’ve been a scholar of the Byron/Shelley circle and had a stack of unread books about them piling up in my home office. I happened to pick up Daisy Hay’s volume, The Young Romantics, and learned that she had found a fragment of Claire Clairmont’s (Mary Shelley’s stepsister) journal, saying that the famous Byron/Shelley summer of “free love” in 1816 had created a “perfect hell” for her. Of course, Claire wrote those words when she was almost eighty (something that I was surprised to learn), impoverished, and living in Florence, Italy, having outlived the two great poets and Mary by many decades. Intrigued, I wondered what it would feel like to outlive everyone who had been part of one’s youth. As the lone remaining figure of that famous quartet, she’d been left behind.

Much of my life, I’ve been a scholar of the Byron/Shelley circle and had a stack of unread books about them piling up in my home office. I happened to pick up Daisy Hay’s volume, The Young Romantics, and learned that she had found a fragment of Claire Clairmont’s (Mary Shelley’s stepsister) journal, saying that the famous Byron/Shelley summer of “free love” in 1816 had created a “perfect hell” for her. Of course, Claire wrote those words when she was almost eighty (something that I was surprised to learn), impoverished, and living in Florence, Italy, having outlived the two great poets and Mary by many decades. Intrigued, I wondered what it would feel like to outlive everyone who had been part of one’s youth. As the lone remaining figure of that famous quartet, she’d been left behind. In that moment, I bonded with Claire and decided to tell her story with the “voice,” that had not been heard yet, but as a fictional memoir.

As I delved into Claire’s life, pieces came together in my thoughts: her illicit love for Byron, her roller-coaster relationship with Mary and Shelley, and her later years in Italy—and I knew I had to tell her story from two perspectives: the young, reckless Claire and the older-but-wiser Claire. We see her at two stages in her life: when she’s seventeen during the summer of 1816 and when she’s 75, living in Italy as an expatriate. This was quite a challenge for me as a writer because her “young” voice is very different from her “mature” voice; she’s an older and wiser woman in much of the book, but still so influenced by what happened to her in her younger days. Then, there was the mystery of her lost daughter with Byron. Her lovers. Her passion for life. It all coalesced into the kind of genre-bending novel that I’ve always wanted to create. Even with my background in the Romantics, I had to complete a lot more research on Claire, pouring over biographies and savoring her marvelously witty letters. She was a remarkable, but rather elusive person as the “almost famous” member of the group, and I found she inspired me with her independent spirit.

As I wrote the book, I healed after successful back surgery, wrote a grant, and had the amazing opportunity to travel to Geneva and Florence with my hubby to research the book. I awoke to find myself with a new life. Like Claire, I had the chance to see Europe with fresh eyes—in my case as an author moving in a new creative direction with my historical fiction. I saw Castle Chillon on Lake Geneva and walked in the steps of the greatness that passed there before me. I saw Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein manuscript (with Percy’s notes) at the Bodmer Museum. I wandered in the Boboli Gardens in Florence, Italy, and imagined Claire’s final years, looking back but still believing in the future.

What began as a challenging physical injury eventually became my own summer of “awakening” into an entirely new life that inspires me each day: every writer’s dream, indeed.

~

Marty Ambrose has been a writer most of her life, consumed with the world of literature whether teaching English at Florida Southwestern State College or creating her own fiction. Her writing career has spanned almost fifteen years, with eight published novels for Avalon Books, Kensington Books, Thomas & Mercer—and, now, Severn House.

Marty Ambrose has been a writer most of her life, consumed with the world of literature whether teaching English at Florida Southwestern State College or creating her own fiction. Her writing career has spanned almost fifteen years, with eight published novels for Avalon Books, Kensington Books, Thomas & Mercer—and, now, Severn House. Two years ago, Marty had the opportunity to apply for a grant that took her to Geneva and Florence to research a new creative direction that builds on her interest in the Romantic poets: historical fiction. Her new book, Claire’s Last Secret, combines memoir and mystery in a genre-bending narrative of the Byron/Shelley “haunted summer,” with Claire Clairmont, as the protagonist/sleuth—the “almost famous” member of the group. The novel spans two eras played out against the backdrop of nineteenth-century Italy and is the first of a trilogy.

Marty lives on an island in Southwest Florida with her husband, former news-anchor, Jim McLaughlin. They are planning a three-week trip to Italy this fall to attend a book festival and research the second book, A Shadowed Fate.

Published on September 03, 2018 04:00

September 1, 2018

Daughter of a Daughter of a Queen by Sarah Bird, a novel about the only female Buffalo Soldier

Many historical novels celebrate strong women whose accomplishments went unheralded in their time. Cathy Williams, the first black woman to serve in the U.S. Army, is a prime example.

Many historical novels celebrate strong women whose accomplishments went unheralded in their time. Cathy Williams, the first black woman to serve in the U.S. Army, is a prime example.Bird’s (Above the East China Sea, 2014) fictionalized version of her life begins in 1864, when Yankee general Philip Sheridan burns the Missouri plantation where she is enslaved and takes her as “contraband” to become his cook’s assistant. Cathy is proud of her illustrious African heritage, and her witty voice and down-to-earth honesty enliven her lengthy tale.

After Appomattox, declining a traditional feminine role, she dresses as a man and enlists as “William Cathay.” Bird’s meaty epic provides abundant, intimate details about Cathy’s life as a Buffalo Soldier: her patrols on the western frontier; the racism of her unit’s white commanding officer; and the harassment she endures from her fellow soldiers, who find her self-protective modesty unnatural. She’s also secretly attracted to her fair-minded sergeant.

“If you don’t push, you never move ahead,” she notes, determining never to be unfree again. An admiring novel about a groundbreaking, mentally tough woman.

Daughter of a Daughter of a Queen will be published next week by St. Martin's Press; I wrote this review for Booklist's August issue. Read more about Cathy (sometimes also called Cathay) Williams at the National Park Service website, though be alert to possible spoilers about the basic outline of her life and service.

Published on September 01, 2018 06:29

August 26, 2018

The Mermaid and Mrs. Hancock by Imogen Hermes Gowar, an entertaining portrait of Georgian society

When one of the sea-captains in his employ returns home, Jonah Hancock, a widowed, middle-aged merchant, is aghast. Captain Jones has sold the Calliope and purchased, instead, a small, shriveled “mermaid.”

When one of the sea-captains in his employ returns home, Jonah Hancock, a widowed, middle-aged merchant, is aghast. Captain Jones has sold the Calliope and purchased, instead, a small, shriveled “mermaid.”In 1785 London, the dead creature is a lucrative commodity. Dubious, but anxious to recoup his costs, Mr. Hancock decides to display it, which eventually introduces him to a brothel-keeper and her courtesans. Among them is the gorgeous Angelica Neal, who seeks a new protector.

Bawdy hijinks ensue – the title predicts the protagonists’ unlikely match – and serious ramifications also. The characters wrestle with their ambitions versus being content with what they have.

Leisurely told, and leavened with a knowing wit, Gowar’s debut, a UK bestseller, brims with colorful period vernacular and delicious phrasings (one woman is “built like an armchair, more upholstered than clothed”; another has a “mouth like low tide”). Concerned with the issue of women’s freedom, it offers a panoramic view of Georgian society: its coffee-houses, street life, class distinctions, and multicultural populace.

A sumptuous historical feast recommended for fans of Jessie Burton’s The Miniaturist.

Imogen Hermes Gowar's The Mermaid and Mrs. Hancock has been available in the UK since January, and it will be published in the US by Harper on September 11th. I submitted this review for Booklist's August issue. If you've already read it, I'll be interested to hear your thoughts!

Published on August 26, 2018 11:34

August 22, 2018

The Air You Breathe by Frances de Pontes Peebles, an epic of friendship, ambition, and music set in 1920s-30s Brazil

A soaring fusion of emotion, intense drama, and the compelling rhythms of Brazilian music, The Air You Breathe belongs to the special category of historical novels that chronicle entire lives – and it does so in enthralling fashion. Its focus is the close, volatile friendship between Dores, a kitchen maid born on the Riacho Doce sugar plantation in northeastern Brazil in 1920, and Graça Pimentel, the owner’s only child.

A soaring fusion of emotion, intense drama, and the compelling rhythms of Brazilian music, The Air You Breathe belongs to the special category of historical novels that chronicle entire lives – and it does so in enthralling fashion. Its focus is the close, volatile friendship between Dores, a kitchen maid born on the Riacho Doce sugar plantation in northeastern Brazil in 1920, and Graça Pimentel, the owner’s only child. The two first meet as girls, when Graça and her parents move into the plantation’s Great House. Graça is strong-willed, selfish, and unmistakably charismatic. They share an education (at Graça’s insistence) and adventures, and an excursion to a big-city concert kindles their musical interest and ambitions for greater achievements. This was a time when LPs and phonographs seemed like magic, and the era is conjured up brilliantly. The girls dream of becoming radio stars together, Graça’s mellifluous voice complementing Dores’ raspier tones. Their path takes them from the diverse nightlife scene of Lapa in Rio to the movie studios of Los Angeles, where Graça, as “Brazilian Bombshell” Sofia Salvador, performs her unique brand of South American entertainment. Alongside Graça’s upward trajectory, Dores partners with a guitarist to write songs the others make famous.

The women’s relationship vacillates between symbiosis and rivalry, all the while shaped by outside forces and unreciprocated desire. Looking back from old age, Dores narrates in a voice as lyrical and achingly passionate as the sambas she writes. She reveals early on that Graça died young, but not how, and the mystery suffuses her tale with longing. Through her wise observations, readers experience their music at every stage: its intimate creation, the showy on-stage performances, and the informal rodas, where their group plays just for themselves. The novel is an intoxicating performance itself, not to be missed by anyone wanting to be wrapped up in a well-told story.

The Air You Breathe was published yesterday in hardcover by Riverhead; I wrote this review for August's Historical Novels Review. Reading it over now, I did gush a bit! It's one of my five-star reads for the year. Peebles has an earlier novel (2008), The Seamstress, also set in Brazil during the same period, and which I haven't read yet, but it's moved up much further on the TBR pile.

Published on August 22, 2018 04:49

August 18, 2018

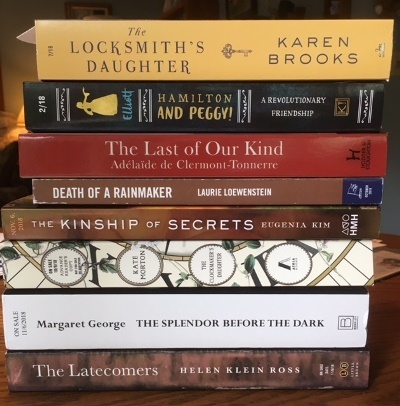

Eight historical novels sitting on Mt. TBR

Hope you're all having a good weekend. I've been using the time to catch up with the TBR, and along those lines, here are eight books I'm looking forward to reading in the near future, time permitting. I took over additional duties at the library in June, so my summer has been more packed than it used to be.

The Locksmith's Daughter, my latest read, is a meaty novel of suspense and intrigue set in Elizabethan England. Review to come.

Hamilton and Peggy!, which I received a copy of during the winter, covers the friendship between Alexander Hamilton and the woman who became his sister-in-law, Peggy Schuyler. It's a YA title, but L.M. Elliott's earlier novel of Renaissance Italy was equally enjoyable for adults, so I'm expecting this one will be too.

The Last of Our Kind, a prize-winner in France, is a literary mystery about love and family secrets set during WWII and the 1970s.

Death of a Rainmaker, a mystery set in Dust Bowl Oklahoma, just received a starred review from Publishers Weekly. I'd enjoyed Laurie Loewenstein's first novel about social change in small-town Illinois, Unmentionables , when it was published in 2014.

Twentieth-century Korea and its people have been the subject of several new historical novels, including Min Jin Lee's Pachinko and Mary Lynn Bracht's White Chrysanthemum. Eugenia Kim's The Kinship of Secrets (which has a blurb from Min Jin Lee) focuses on two sisters divided by the Korean War.

Kate Morton's newest gothic saga The Clockmaker's Daughter (yes, another "daughter" book) is one I've been anticipating for months, since I've loved all of her earlier books.

In The Splendor Before the Dark, Margaret George will conclude her two-book saga of about Emperor Nero. I have a review due in 10 days so had better get cracking...

Lastly, The Latecomers is about an Irish housemaid and an old New England house with lots of secrets. There's a detailed family tree at the beginning, which is enough to catch my attention.

Will you be putting any of these on your own TBRs?

The Locksmith's Daughter, my latest read, is a meaty novel of suspense and intrigue set in Elizabethan England. Review to come.

Hamilton and Peggy!, which I received a copy of during the winter, covers the friendship between Alexander Hamilton and the woman who became his sister-in-law, Peggy Schuyler. It's a YA title, but L.M. Elliott's earlier novel of Renaissance Italy was equally enjoyable for adults, so I'm expecting this one will be too.

The Last of Our Kind, a prize-winner in France, is a literary mystery about love and family secrets set during WWII and the 1970s.

Death of a Rainmaker, a mystery set in Dust Bowl Oklahoma, just received a starred review from Publishers Weekly. I'd enjoyed Laurie Loewenstein's first novel about social change in small-town Illinois, Unmentionables , when it was published in 2014.

Twentieth-century Korea and its people have been the subject of several new historical novels, including Min Jin Lee's Pachinko and Mary Lynn Bracht's White Chrysanthemum. Eugenia Kim's The Kinship of Secrets (which has a blurb from Min Jin Lee) focuses on two sisters divided by the Korean War.

Kate Morton's newest gothic saga The Clockmaker's Daughter (yes, another "daughter" book) is one I've been anticipating for months, since I've loved all of her earlier books.

In The Splendor Before the Dark, Margaret George will conclude her two-book saga of about Emperor Nero. I have a review due in 10 days so had better get cracking...

Lastly, The Latecomers is about an Irish housemaid and an old New England house with lots of secrets. There's a detailed family tree at the beginning, which is enough to catch my attention.

Will you be putting any of these on your own TBRs?

Published on August 18, 2018 12:00

August 16, 2018

Cometh the Hour by Annie Whitehead, a novel of war, religion, love, and family in 7th-century Britain

With a careful hand and keen appreciation for the era’s material culture, Annie Whitehead, the inaugural winner of the HWA Dorothy Dunnett Short Story Competition, depicts five tumultuous decades in early medieval Britain. In her third novel, she puts a human face on the Game of Thrones-style drama involving the kingdoms of Deira, Bernicia, Mercia, and East Anglia.

With a careful hand and keen appreciation for the era’s material culture, Annie Whitehead, the inaugural winner of the HWA Dorothy Dunnett Short Story Competition, depicts five tumultuous decades in early medieval Britain. In her third novel, she puts a human face on the Game of Thrones-style drama involving the kingdoms of Deira, Bernicia, Mercia, and East Anglia.The story spans from 604 AD – when the devious Aylfrith of Bernicia attacks neighboring Deira, abducting the king’s sister, Acha, and sending her other brother, Edwin, into exile – up through the Battle of the Winwaed in the year 655. Every personage once lived.

The family tree and dramatis personae prove critical, since there are many characters, viewpoints, and relationships to track. The action sometimes feels episodic, and some significant historical events aren’t shown firsthand, but subsequent scenes make it clear what happened.

The battle scenes, seen from close-up, are fierce and forceful. “War is for men, but it is the women who suffer,” states one newly-made widow, all too correctly, and Whitehead devotes significant attention to the women, including peace-weaver brides, mothers, abbesses, and loyal wives set aside after their husbands tire of them.

Among the most sympathetic portrayals are kind-hearted Carinna (Cwenburh), a princess of Mercia, and Derwena, whose love-match with Carinna’s cousin, Penda, helps hold their large family together. Then there’s Queen Bertana of East Anglia, whose scenes are brief but memorable. Her reaction to her husband Redwald’s religious conversion is a hoot!

Penda of Mercia, a pagan in an increasingly Christianized land, emerges as the strongest hero. Alliances frequently shift, with motivations changing over time, and the story demonstrates how overzealous ambition can warp one’s nature. As a result, not all characters retain readers’ sympathy throughout, and the transitions are skillfully done. A solid choice for fans of the period.

Cometh the Hour was published in 2017 by FeedARead; I reviewed it for August's Historical Novels Review. Since it's labeled as book 1 of the Tales of the Iclingas (the name of the Mercian dynasty from the period), I'm guessing that means there's more to come, which is good news.

Published on August 16, 2018 05:00

August 12, 2018

Beneath an Indian Sky by Renita D'Silva, a multi-period saga set in England and India

Author D’Silva transports readers to her native India in a new multi-period novel exploring her frequent themes of difficult family dynamics and the limited choices open to the country’s daughters.

Author D’Silva transports readers to her native India in a new multi-period novel exploring her frequent themes of difficult family dynamics and the limited choices open to the country’s daughters. In 1936, Mary Brigham, raised in her aunt and uncle’s London home, is preparing her debutante season and planning to be presented at court. An atypical historical novel heroine, she dreams only of marrying well and raising a family—at least until an old friend of her late parents alludes to their lives in India and a terrible tragedy she can’t recall.

Chapters set eleven years earlier introduce Sita, a girl from a wealthy Indian household, and show how her unusual childhood friendship with Mary developed. In the beginning, both Mary and Sita are equally sympathetic: Mary for her sorrowful past and determination to face up to it, and Sita because she can never attain her parents’ approval.

Despite some confusing aspects of their juxtaposed narratives—the girls’ ages aren’t mentioned, for one—the novel smoothly depicts their transformations into adulthood. Sita ends up marrying a prince and moving into his opulent palace, where her mother-in-law makes her life miserable. Years later, what happens at Mary and Sita’s reunion twists their lives irrevocably and leads to a devastating secret left for Sita’s granddaughter, Priya, to uncover decades later. Priya, a modern documentary filmmaker depressed over her husband’s infidelity, plays an unfortunately small role, although her presence serves to bring the earlier stories full circle.

The plot gets over-the-top dramatic toward the end, and colonial Indian politics remain mostly in the background. Also, too many women have the tendency to faint when confronted with bad news. Still, readers desiring a satisfying excursion to a land of jasmine breezes and delicious cuisine may wish to follow the story and indulge in all the lush atmospheric details.

Beneath an Indian Sky was published by Bookouture in 2018; I read it from a NetGalley copy and wrote this review for August's Historical Novels Review. D'Silva has written a number of family sagas, many of which have historical elements, including A Daughter's Courage (which I reviewed last year).

Published on August 12, 2018 07:39

August 8, 2018

Susan Spann's Trial on Mount Koya, a Shinobi mystery of 16th-century Japan

One might expect a Shingon Buddhist temple to be a peaceful site of sanctuary, but the opposite holds true in the atmospheric sixth novel of Susan Spann’s Shinobi Mysteries.

One might expect a Shingon Buddhist temple to be a peaceful site of sanctuary, but the opposite holds true in the atmospheric sixth novel of Susan Spann’s Shinobi Mysteries. Set in 1565, this entry brings her protagonists – the shinobi assassin Hiro Hattori and the Jesuit priest whose life he's pledged to protect, Father Mateo – to the remote summit of Mount Koya. Hiro has been sent by his cousin, a master ninja, to carry a directive to a spy who’s been living there as a priest. Having left their housekeeper Ana behind at a nyonindo (women’s hall), since females aren’t allowed to enter the sacred precincts atop the mountain, they approach the temple and are welcomed by the very man, Ringa, that Hiro hopes to find.

However, shortly after Hiro communicates his message to Ringa, a brutal snowstorm enshrouds the temple, forming the right conditions for a locked room-style mystery. Then, later that night, Ringa is discovered horribly murdered. Subsequent deaths follow at regular intervals, with the bodies posed as Buddhist judges of the afterlife. Creepily, the personalities of the late priests seem to resemble those particular Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. The small population at the temple is quickly dwindling, with the perpetrator clearly among them – and if the pattern holds true, Father Mateo could be next.

While Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None is the story’s inspiration, the author spins the basic outline into a mystery specific to her chosen cast and setting, making it a very clever homage indeed. There are a multitude of priests of diverse ages, talents, and backgrounds. As is often the case with many characters introduced at once, their personalities take a bit to settle in, but their particular perspectives emerge in time. On site as well are a mysterious pilgrim and his son, and as outsiders, they fall under suspicion.

The growing friendship between Hiro and Father Mateo is a highlight. Consumed by revenge and loss after his lover’s death in the previous book, Hiro isn’t able to acknowledge how much this affects his judgment, but Father Mateo provides support and sage advice. Cat lovers will appreciate the prominence and entertaining personality of Hiro’s cat, Gato, in this entry, too.

What puzzles the detective pair is not only the bizarre nature of the murders, but also the motive. Perhaps it derives from an internal power struggle, or it could be a madman’s work. As the stakes get higher, the suspense level rises. Fortunately, Spann plays fair with her readers, since -- as it turns out -- the clues are present from the outset. Readers may be tempted to reread from the beginning, noting how well the mystery was constructed.

Trial on Mount Koya was published in July by Seventh Street. Thanks to the publisher and Historical Fiction Virtual Book Tours for the e-galley copy via Edelweiss.

During the Blog Tour, five copies of Trial on Mount Koya are up for grabs. Note that because this is the last stop on the tour, the deadline is tonight. To enter, please enter via the Gleam form below. Good luck!

Giveaway Rules

– Giveaway ends at 11:59pm EST on August 8th. You must be 18 or older to enter.

– Giveaway is open to US residents only.

– Only one entry per household.

– All giveaway entrants agree to be honest and not cheat the systems; any suspect of fraud is decided upon by blog/site owner and the sponsor, and entrants may be disqualified at our discretion.

– Winner has 48 hours to claim prize or new winner is chosen.

Trial on Mount Koya

Published on August 08, 2018 05:00

August 6, 2018

The Sea Queen by Linnea Hartsuyker, a tale of Viking-era Norway

The “sea queen” is Svanhild Eysteinsdotter, a strong-willed woman with a difficult path ahead. In ninth-century Norway, six years after events in The Half-Drowned King (2017), Svanhild loves the seafaring life she led with her husband, the raider Solvi, but knows her intellectually-minded son’s needs take priority.

The “sea queen” is Svanhild Eysteinsdotter, a strong-willed woman with a difficult path ahead. In ninth-century Norway, six years after events in The Half-Drowned King (2017), Svanhild loves the seafaring life she led with her husband, the raider Solvi, but knows her intellectually-minded son’s needs take priority.Alongside their marital strife, Solvi pursues revenge against Harald, Norway’s king. He’s not alone. Throughout the country and elsewhere, disaffected exiles and noblemen resentful of Harald’s taxes rise up against him. Svanhild’s brother, Ragnvald, king of Sogn, is Harald’s loyal man, and as pockets of rebellion join forces, helping Harald achieve a united Norway becomes increasingly dangerous.

Although less action-oriented than its predecessor, this second in the Golden Wolf Saga captures the era’s warlike atmosphere, where blood-feuds last generations; an early incident of stark brutality haunts Ragnvald long afterward. Through her multi-faceted characters, Hartsuyker adeptly evokes female alliances, the complications of love and passion, and vengeance both terrible and triumphant. She juggles many subplots and settings effectively, with scenes moving from Norway’s harsh, picturesque coast to sulfurous Iceland and Dublin’s muddy harbor.

The Sea Queen will be published by Harper on August 14th. I wrote this review for Booklist's August issue. I also reviewed the first book last year and look forward to reading the final installment, The Golden Wolf, next summer.

Published on August 06, 2018 04:00

August 1, 2018

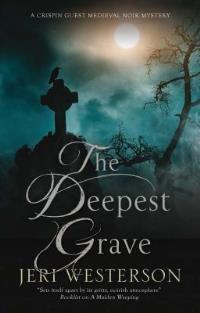

The Haunts of London: Jeri Westerson's medieval mystery The Deepest Grave

In his entertaining 11th adventure, Crispin Guest, known throughout late 14th-century London as the Tracker, has his hands full with two perplexing cases.

In his entertaining 11th adventure, Crispin Guest, known throughout late 14th-century London as the Tracker, has his hands full with two perplexing cases.The first is rather grisly: Father Bulthius of St. Modwen’s asks him to investigate the “demon’s march” of corpses from the graveyard. The dead are supposedly unearthing themselves and dragging their coffins around after dark. Crispin can hardly believe it until he visits the parish church and sees a shadowy figure carrying a heavy object, and then the empty grave. Something mysterious is clearly afoot. His apprentice, Jack Tucker, a devout lad, is too creeped out to be enthusiastic about their venture but dutifully follows where his master leads.

In the second instance, Crispin receives a note from an old lover, Philippa Walcote, who’s now a prosperous mercer’s wife. Her seven-year-old son, Christopher, is accused of murdering his father’s neighbor and competitor; even worse, the boy confessed to the crime. With nowhere else to turn, Philippa requests Crispin’s help.

The novel offers a compelling balance of situations and emotions. There are some hilarious moments spurred by Jack’s reluctance to go skulking about amongst the graves (who can blame him?). Crispin, a disgraced knight and longtime bachelor, also broods a bit about his unusual household. Jack and his wife, Isabel, are living at Crispin’s place and are expecting their first child imminently, and Crispin is sort-of-but-not-quite a member of Jack’s growing family. Both his home life, and meeting Philippa and her son, leave Crispin pondering what might have been.

Westerson wonderfully evokes the streets, taverns, and other haunts of medieval London, when the city’s outskirts were still rural, as well as period mentalities (among other mysteries, a religious relic appears to have a mind of its own). Crispin’s backstory is woven in so well that newcomers won’t feel lost, either.

The Deepest Grave is published today by Severn House; thanks to the publisher for NetGalley access. I reviewed the novel for August's Historical Novels Review.

Published on August 01, 2018 04:00