Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 52

May 6, 2019

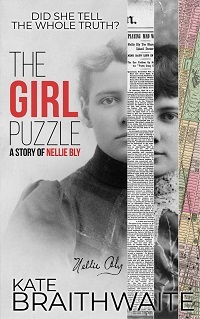

Interview with Kate Braithwaite, author of The Girl Puzzle: A Story of Nellie Bly

Kate Braithwaite's newest novel The Girl Puzzle, published by Crooked Cat this week, provides an insightful look into the exploits and motivations of famed investigative reporter Nellie Bly (real name Elizabeth Cochrane). In addition to taking us into the Blackwell’s Island Lunatic Asylum along with her in 1887, the novel gives us the viewpoint of her secretary Beatrice Alexander, who, decades later, types up notes about her employer's groundbreaking experiences. I'm happy to welcome Kate back to the blog today.

You’ve given your novel an intriguing structure, with the story moving between Elizabeth Cochrane’s undercover expose of the conditions on Blackwell’s Island in 1887, for which she became famous, and her later life in the 1920s, which isn’t well known at all. How did you come up with this idea?

My starting point with writing about Nellie Bly/Elizabeth Cochrane was very much the asylum expose. I found that adventure fascinating: I wanted to write about it, and I knew it was something I’d like to read a novel about. But I felt there were obstacles. Firstly – she’d already written about it herself. What would I be adding to that? Secondly, many potential readers would begin the story already knowing that Nellie was released from the asylum and went on travel solo around the world. I was concerned that might mean the story lacked suspense.

My starting point with writing about Nellie Bly/Elizabeth Cochrane was very much the asylum expose. I found that adventure fascinating: I wanted to write about it, and I knew it was something I’d like to read a novel about. But I felt there were obstacles. Firstly – she’d already written about it herself. What would I be adding to that? Secondly, many potential readers would begin the story already knowing that Nellie was released from the asylum and went on travel solo around the world. I was concerned that might mean the story lacked suspense.

My view changed, though, when I discovered there were contradictory accounts of her time in the asylum – contradictions given by Nellie herself, as well as in other competing newspapers. And by that time, I’d also learned how much more there was to Nellie Bly’s life story and was keen to somehow share that too. When I read that in her fifties, Nellie Bly lived in a hotel suite in New York City and ran an informal adoption agency for children, I decided to structure the novel with two timelines.

Is Beatrice Alexander based upon anyone in particular?

Beatrice Alexander was the name of one of Nellie Bly’s secretaries in 1920. She was interviewed in an unpublished thesis, Nellie Bly: A Biographical Sketch, that I was able to read thanks to Columbia University. That told me some things about Nellie Bly’s later life, but nothing really about Beatrice. So although based on a real person, she’s a fictional character who – in some ways – walks in my shoes. She’s impressed by Nellie Bly. She admires her. She wants to know more about her and understand her character. She even goes to look at the Temporary Home for Women on 2nd Avenue and tries to imagine Nellie Bly there. I have Beatrice doing that in October, 1920, just as I did it myself in October, 2018. It wasn’t a conscious decision, but looking at it now, I’d say that if Beatrice is based on anyone, she is based on me.

What was your reaction, upon first reading what Elizabeth and her fellow patients endured in the asylum?

A weird sense of disappointment! There were many shocking details, but Nellie’s writing is very matter of fact and abrupt. She evens says herself that she tells her story “as plainly as possible,” because she was there as a journalist and tasked with reporting on facts, not feelings. The beatings, the hair-pulling, the bullying incidents and acts of violence certainly make for difficult reading at points. But at the end I didn’t feel that I learned very much about Nellie Bly herself. I wanted to know more. How did she get the assignment? What journalism experience did she already have? She was only 23 at the time. How did the asylum experience affect her? Did she ever see anyone she met there again? What happened to the other patients? How did the doctors and nurses in the asylum react when Nellie’s story was published?

How did you research Nellie Bly’s character during her later life?

My main source for Nellie’s life, outside her own newspaper reports, was Brooke Kroeger’s comprehensive biography, Nellie Bly: Daredevil. Reporter. Feminist. It’s over 600 pages long, amply illustrating by that fact alone that there was much more to Nellie Bly’s life than the asylum expose and her solo trip around the world – amazing as both those feats were. Kroeger’s biography is incredibly detailed and also meticulously indexed. I was able to obtain source material for many of the episodes she details – for example, the thesis I mentioned earlier where Beatrice Alexander was interviewed. My local library helped obtain some of Nellie’s later articles, too. For anyone who wants to know more about Nellie’s life and writing, I’d recommend Kroeger’s biography as well as Nellie Bly, Around the World in Seventy-Two Days and Other Writings, edited by Jean Marie Lutes. This collection includes her first article, "The Girl Puzzle," her two original madhouse reports, her round the world expedition and some much later stories during and after World War I.

author Kate BraithwaiteAs a British author writing about American characters, are there any language differences you had to pay attention to?

author Kate BraithwaiteAs a British author writing about American characters, are there any language differences you had to pay attention to?

Although I have lived in the U.S. since 2010 and am a naturalized citizen, I grew up in Britain and lived there for most of my life. I’m very aware of the differences between U.S. and U.K. English and approached writing The Girl Puzzle with this very much in mind. Nellie Bly was a proud American woman – in fact she disliked the British! – and I was as keen to be true to her story in this aspect as much as any other. Spelling was obviously a starting point. Then there are many everyday words that are different – you say purse, I say handbag, you say bangs, I say fringe, you say two weeks, I say fortnight and so on. Hopefully I kept my British vocabulary firmly under control. If I was setting out to write a contemporary novel with modern Americans as my main characters, I actually think my task might be harder than it was here. As I wrote I read and re-read Nellie Bly’s work across her working life and have the hope that my British educated writing style fits with that period fairly comfortably. Of course, I could be wrong! I did ask early readers to look out for ‘British-isms’ and have my fingers crossed that American readers are not disappointed in the book.

Did you get to travel to any of the sites covered in the novel?

Absolutely. Although I’d love to go to the haunts of Nellie’s early life in Pittsburgh, Cochran’s Mills and Apollo, I didn’t make it over there, choosing instead to focus on New York where all the action takes place. The Blackwell’s Island Lunatic Asylum still stands, at least in part. It’s now an apartment building and the wings are new, but the central octagon is the same, in its exterior at least, as it was in 1887. Standing outside the asylum and looking over the East River at Manhattan, just as Nellie Bly did, was a really memorable experience for me. I also followed in her footsteps on the day she began her adventure, walking from her boarding house on West Ninety-Sixth Street, through Central Park and all the way down to 84 Second Avenue. Bellevue Hospital, a location Nellie visits in both timelines, looks very different now but her home in the 1920’s, (now Herald Towers, then the McAlpin Hotel) is just next to Macy’s Department Store. I spent some time there, imagining Miss Bly and her staff coming and going, although I had to remember that the Empire State building, which looms up behind it, wasn’t completed until 1931.

~

Kate Braithwaite grew up in Edinburgh but now lives with her family in the Brandywine Valley in Pennsylvania. Her daughter doesn’t think Kate should describe herself as a history nerd, but that’s exactly what she is. Always on the hunt for lesser known stories from the past, Kate’s books have strong female characters, rich settings and dark secrets. The Girl Puzzle is her third novel. For more information, see her website at www.kate-braithwaite.com and on social media as follows:

Facebook | Twitter (Girl Puzzle) | Twitter (Author) | BookBub | Goodreads

You’ve given your novel an intriguing structure, with the story moving between Elizabeth Cochrane’s undercover expose of the conditions on Blackwell’s Island in 1887, for which she became famous, and her later life in the 1920s, which isn’t well known at all. How did you come up with this idea?

My starting point with writing about Nellie Bly/Elizabeth Cochrane was very much the asylum expose. I found that adventure fascinating: I wanted to write about it, and I knew it was something I’d like to read a novel about. But I felt there were obstacles. Firstly – she’d already written about it herself. What would I be adding to that? Secondly, many potential readers would begin the story already knowing that Nellie was released from the asylum and went on travel solo around the world. I was concerned that might mean the story lacked suspense.

My starting point with writing about Nellie Bly/Elizabeth Cochrane was very much the asylum expose. I found that adventure fascinating: I wanted to write about it, and I knew it was something I’d like to read a novel about. But I felt there were obstacles. Firstly – she’d already written about it herself. What would I be adding to that? Secondly, many potential readers would begin the story already knowing that Nellie was released from the asylum and went on travel solo around the world. I was concerned that might mean the story lacked suspense.My view changed, though, when I discovered there were contradictory accounts of her time in the asylum – contradictions given by Nellie herself, as well as in other competing newspapers. And by that time, I’d also learned how much more there was to Nellie Bly’s life story and was keen to somehow share that too. When I read that in her fifties, Nellie Bly lived in a hotel suite in New York City and ran an informal adoption agency for children, I decided to structure the novel with two timelines.

Is Beatrice Alexander based upon anyone in particular?

Beatrice Alexander was the name of one of Nellie Bly’s secretaries in 1920. She was interviewed in an unpublished thesis, Nellie Bly: A Biographical Sketch, that I was able to read thanks to Columbia University. That told me some things about Nellie Bly’s later life, but nothing really about Beatrice. So although based on a real person, she’s a fictional character who – in some ways – walks in my shoes. She’s impressed by Nellie Bly. She admires her. She wants to know more about her and understand her character. She even goes to look at the Temporary Home for Women on 2nd Avenue and tries to imagine Nellie Bly there. I have Beatrice doing that in October, 1920, just as I did it myself in October, 2018. It wasn’t a conscious decision, but looking at it now, I’d say that if Beatrice is based on anyone, she is based on me.

What was your reaction, upon first reading what Elizabeth and her fellow patients endured in the asylum?

A weird sense of disappointment! There were many shocking details, but Nellie’s writing is very matter of fact and abrupt. She evens says herself that she tells her story “as plainly as possible,” because she was there as a journalist and tasked with reporting on facts, not feelings. The beatings, the hair-pulling, the bullying incidents and acts of violence certainly make for difficult reading at points. But at the end I didn’t feel that I learned very much about Nellie Bly herself. I wanted to know more. How did she get the assignment? What journalism experience did she already have? She was only 23 at the time. How did the asylum experience affect her? Did she ever see anyone she met there again? What happened to the other patients? How did the doctors and nurses in the asylum react when Nellie’s story was published?

How did you research Nellie Bly’s character during her later life?

My main source for Nellie’s life, outside her own newspaper reports, was Brooke Kroeger’s comprehensive biography, Nellie Bly: Daredevil. Reporter. Feminist. It’s over 600 pages long, amply illustrating by that fact alone that there was much more to Nellie Bly’s life than the asylum expose and her solo trip around the world – amazing as both those feats were. Kroeger’s biography is incredibly detailed and also meticulously indexed. I was able to obtain source material for many of the episodes she details – for example, the thesis I mentioned earlier where Beatrice Alexander was interviewed. My local library helped obtain some of Nellie’s later articles, too. For anyone who wants to know more about Nellie’s life and writing, I’d recommend Kroeger’s biography as well as Nellie Bly, Around the World in Seventy-Two Days and Other Writings, edited by Jean Marie Lutes. This collection includes her first article, "The Girl Puzzle," her two original madhouse reports, her round the world expedition and some much later stories during and after World War I.

author Kate BraithwaiteAs a British author writing about American characters, are there any language differences you had to pay attention to?

author Kate BraithwaiteAs a British author writing about American characters, are there any language differences you had to pay attention to? Although I have lived in the U.S. since 2010 and am a naturalized citizen, I grew up in Britain and lived there for most of my life. I’m very aware of the differences between U.S. and U.K. English and approached writing The Girl Puzzle with this very much in mind. Nellie Bly was a proud American woman – in fact she disliked the British! – and I was as keen to be true to her story in this aspect as much as any other. Spelling was obviously a starting point. Then there are many everyday words that are different – you say purse, I say handbag, you say bangs, I say fringe, you say two weeks, I say fortnight and so on. Hopefully I kept my British vocabulary firmly under control. If I was setting out to write a contemporary novel with modern Americans as my main characters, I actually think my task might be harder than it was here. As I wrote I read and re-read Nellie Bly’s work across her working life and have the hope that my British educated writing style fits with that period fairly comfortably. Of course, I could be wrong! I did ask early readers to look out for ‘British-isms’ and have my fingers crossed that American readers are not disappointed in the book.

Did you get to travel to any of the sites covered in the novel?

Absolutely. Although I’d love to go to the haunts of Nellie’s early life in Pittsburgh, Cochran’s Mills and Apollo, I didn’t make it over there, choosing instead to focus on New York where all the action takes place. The Blackwell’s Island Lunatic Asylum still stands, at least in part. It’s now an apartment building and the wings are new, but the central octagon is the same, in its exterior at least, as it was in 1887. Standing outside the asylum and looking over the East River at Manhattan, just as Nellie Bly did, was a really memorable experience for me. I also followed in her footsteps on the day she began her adventure, walking from her boarding house on West Ninety-Sixth Street, through Central Park and all the way down to 84 Second Avenue. Bellevue Hospital, a location Nellie visits in both timelines, looks very different now but her home in the 1920’s, (now Herald Towers, then the McAlpin Hotel) is just next to Macy’s Department Store. I spent some time there, imagining Miss Bly and her staff coming and going, although I had to remember that the Empire State building, which looms up behind it, wasn’t completed until 1931.

~

Kate Braithwaite grew up in Edinburgh but now lives with her family in the Brandywine Valley in Pennsylvania. Her daughter doesn’t think Kate should describe herself as a history nerd, but that’s exactly what she is. Always on the hunt for lesser known stories from the past, Kate’s books have strong female characters, rich settings and dark secrets. The Girl Puzzle is her third novel. For more information, see her website at www.kate-braithwaite.com and on social media as follows:

Facebook | Twitter (Girl Puzzle) | Twitter (Author) | BookBub | Goodreads

Published on May 06, 2019 04:00

May 3, 2019

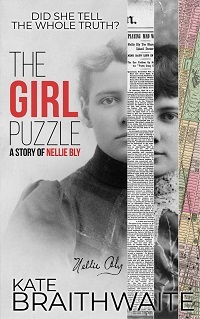

Uncovering little-known chapters in history through family lore, an essay by Julie Zuckerman, author of The Book of Jeremiah

A warm welcome and happy release day today to Julie Zuckerman, author of the novel-in-stories The Book of Jeremiah. I read her post avidly since I seek out fiction that's connected to family history research. Hope you'll appreciate her essay as well.

~

Uncovering Little-Known Chapters in History

Through Family Lore Julie Zuckerman

From an early age, I was fascinated by the family tidbits I’d hear from my mother and other relatives. I made elaborate family trees, thrilled I could fill in the names and birthplaces of at least eight of my great-great-great-grandparents. Like most Jews of Eastern European descent, my relatives were born in shtetls, small villages, in the Galicia region of what is now Poland, or in areas of Russia or Lithuania. The migration to the United States of my immediate ancestors began with one set of great-grandparents, who arrived in the 1880s on their honeymoon, and finished in 1929, when my then-17-year-old grandmother and her two younger brothers joined their father and an older sister already in America.

I captured micro-details in hand-written notes or early word processing programs (“He was tall and had a sense of humor” or “Her three children were very bright”). Some bits had slightly more narrative to them, such as this note from a conversation with my great-uncle, who never lost his thick Galician accent: [sic] “There was no problems. We had no problems, but in 1919 there was a pogrom and 22 people died. The pogrom was on a Thursday morning…”

With so many family details and characters filling my head, naturally I used many of them as inspiration for various plotlines and backstories in my new novel-in-stories, The Book of Jeremiah. There is mention of someone dressed as a woman and smuggled out of Russia to avoid the Czar’s army (inspired by my great-grandfather), civil rights volunteers in Mississippi during Freedom Summer (after writing the story, I learned my uncle was one of them); and Jeremiah himself, who serves in the U.S. Signal Corps during World War II (inspired by my grandfather).

The Book of Jeremiah spans eight decades, from the Depression to the modern age, with stories jumping back and forth in time. Conducting research was one of the highlights of the writing. I’d delve into a historical event, or Google things like “Depression-era Bridgeport” to see photographs and get an idea for a detail, and I’d come away with new ideas for characters or the plot.

One example that unfolded this way was the knowledge that my relatives were—and are—Zionists who believed Jews should have a homeland. For example, David Ben-Gurion, who later became Israel’s first Prime Minister, stayed with my great-grandparents on an early fundraising trip to Albany. The need to realize this vision became more acute, of course, once the horrors of the Holocaust were well-known.

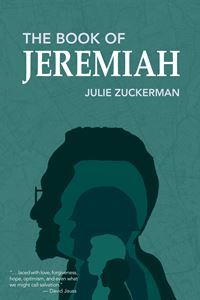

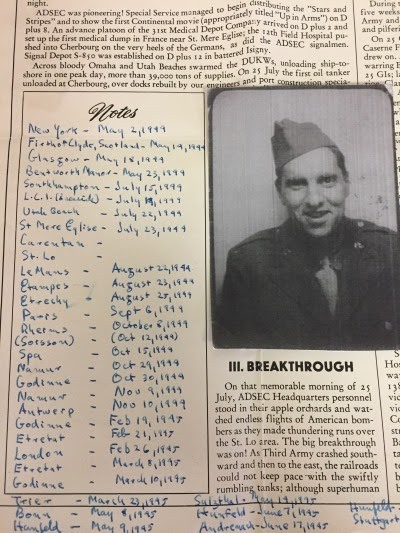

Photo of the author's grandfather in the Army

Photo of the author's grandfather in the Army

In 1947, the United Nations approved the Partition Plan to create a Jewish homeland in Palestine, but it was clear the surrounding Arab countries were gearing up for war. Shortly after the UN vote, President Truman—urged on by his formidable Secretary of State George Marshall—invoked the Neutrality Act, making it illegal to supply arms to either side of the brewing conflict. Frightened by the prospect of what would happen to the 600,000 Jews in Palestine, not a few of whom had already survived the concentration camps, American Jews mobilized their support behind The Jewish Agency, the highest political body of the Jewish people, and its defense wing, the Haganah. My great-uncle and my cousin, a teenager at the time, became part of network of gunrunners, smuggling arms and supplies to the Haganah.

My uncle and a friend would pack up guns, their wives serving as lookouts, and they’d make deliveries of the packages to somewhere in Queens, with “Hadassah” written on the boxes. My cousin remembers walking through Grand Central Station, nervous as hell, carrying a stash of guns in his gym bag. The gunrunners were helped by dozens of non-Jews as well: Irish-American longshoremen and police officers, even the mayor of New York, who sympathized with their cause.

In researching this chapter of American Jewish history and working this family tidbit into my story “Clandestiny,” the most fascinating character I came across was Adolph “Al” Schwimmer. Schwimmer was a pilot in the U.S. Air Force in World War II and awarded a medal of valor for his service. In 1947, at the request of Ben Gurion, he left his job as a flight engineer at TWA to recruit fellow airmen and buy planes for the Israeli Air Force-in-formation. He headed a vast aircraft smuggling operation, which included purchasing and refurbishing used aircraft, including U.S. military planes, which were flown to Israel via Florida and Czechoslovakia under the guise of a fictious Panamanian airline. Over 30 bombers and cargo planes were acquired in this manner. Schwimmer was nearly arrested several times before fleeing to Canada and then to Israel, where he continued to help the nascent Israeli Air Force during the War of Independence. Schwimmer – Ben Gurion said at the time – was the Diaspora’s single-most important contribution to the young state’s survival.

author Julie ZuckermanShortly after his return to the United States in 1949, Schwimmer and five others were tried and convicted of violating the Neutrality Act. The judge stripped Schwimmer of his voting rights and his veteran benefits and slapped him with a $10,000 fine, but he did not sentence him to any jail time. Schwimmer went on to move to Israel, where he founded Israel’s largest aerospace company. Though Schwimmer never asked for a pardon – he worried that a second Holocaust might be perpetrated should Israel lose the war—but President Bill Clinton granted him one in 2001.

author Julie ZuckermanShortly after his return to the United States in 1949, Schwimmer and five others were tried and convicted of violating the Neutrality Act. The judge stripped Schwimmer of his voting rights and his veteran benefits and slapped him with a $10,000 fine, but he did not sentence him to any jail time. Schwimmer went on to move to Israel, where he founded Israel’s largest aerospace company. Though Schwimmer never asked for a pardon – he worried that a second Holocaust might be perpetrated should Israel lose the war—but President Bill Clinton granted him one in 2001.

A few months after I wrote the first draft “Clandestiny,” in which one of plotlines takes inspiration from Schwimmer’s story, he passed away on his 94th birthday. The full story of how American Jews like Schwimmer and my relatives helped the young Jewish state is too complex for the space allotted, though I remember thinking at the time of my research that if I should ever write a biography, I would be honored to write his. According to one obituary, Schwimmer resisted all appeals to write his memoir, asking, “Who would be interested?” From the small amount that I learned through my research, I can imagine many who would be.

~

Julie Zuckerman’s fiction and nonfiction have appeared in a variety of publications, including The SFWP Quarterly, The MacGuffin, Salt Hill, Sixfold, Crab Orchard Review, Ellipsis, The Coil, and others. The Book of Jeremiah, her debut novel-in-stories, was the runner-up in the 2018 Press 53 Award for Short Fiction, and is due in May 2019. A native of Connecticut, she resides in Modiin, Israel, with her husband and four children. Learn more at https://www.juliezuckerman.com/

~

Uncovering Little-Known Chapters in History

Through Family Lore Julie Zuckerman

From an early age, I was fascinated by the family tidbits I’d hear from my mother and other relatives. I made elaborate family trees, thrilled I could fill in the names and birthplaces of at least eight of my great-great-great-grandparents. Like most Jews of Eastern European descent, my relatives were born in shtetls, small villages, in the Galicia region of what is now Poland, or in areas of Russia or Lithuania. The migration to the United States of my immediate ancestors began with one set of great-grandparents, who arrived in the 1880s on their honeymoon, and finished in 1929, when my then-17-year-old grandmother and her two younger brothers joined their father and an older sister already in America.

I captured micro-details in hand-written notes or early word processing programs (“He was tall and had a sense of humor” or “Her three children were very bright”). Some bits had slightly more narrative to them, such as this note from a conversation with my great-uncle, who never lost his thick Galician accent: [sic] “There was no problems. We had no problems, but in 1919 there was a pogrom and 22 people died. The pogrom was on a Thursday morning…”

With so many family details and characters filling my head, naturally I used many of them as inspiration for various plotlines and backstories in my new novel-in-stories, The Book of Jeremiah. There is mention of someone dressed as a woman and smuggled out of Russia to avoid the Czar’s army (inspired by my great-grandfather), civil rights volunteers in Mississippi during Freedom Summer (after writing the story, I learned my uncle was one of them); and Jeremiah himself, who serves in the U.S. Signal Corps during World War II (inspired by my grandfather).

The Book of Jeremiah spans eight decades, from the Depression to the modern age, with stories jumping back and forth in time. Conducting research was one of the highlights of the writing. I’d delve into a historical event, or Google things like “Depression-era Bridgeport” to see photographs and get an idea for a detail, and I’d come away with new ideas for characters or the plot.

One example that unfolded this way was the knowledge that my relatives were—and are—Zionists who believed Jews should have a homeland. For example, David Ben-Gurion, who later became Israel’s first Prime Minister, stayed with my great-grandparents on an early fundraising trip to Albany. The need to realize this vision became more acute, of course, once the horrors of the Holocaust were well-known.

Photo of the author's grandfather in the Army

Photo of the author's grandfather in the ArmyIn 1947, the United Nations approved the Partition Plan to create a Jewish homeland in Palestine, but it was clear the surrounding Arab countries were gearing up for war. Shortly after the UN vote, President Truman—urged on by his formidable Secretary of State George Marshall—invoked the Neutrality Act, making it illegal to supply arms to either side of the brewing conflict. Frightened by the prospect of what would happen to the 600,000 Jews in Palestine, not a few of whom had already survived the concentration camps, American Jews mobilized their support behind The Jewish Agency, the highest political body of the Jewish people, and its defense wing, the Haganah. My great-uncle and my cousin, a teenager at the time, became part of network of gunrunners, smuggling arms and supplies to the Haganah.

My uncle and a friend would pack up guns, their wives serving as lookouts, and they’d make deliveries of the packages to somewhere in Queens, with “Hadassah” written on the boxes. My cousin remembers walking through Grand Central Station, nervous as hell, carrying a stash of guns in his gym bag. The gunrunners were helped by dozens of non-Jews as well: Irish-American longshoremen and police officers, even the mayor of New York, who sympathized with their cause.

In researching this chapter of American Jewish history and working this family tidbit into my story “Clandestiny,” the most fascinating character I came across was Adolph “Al” Schwimmer. Schwimmer was a pilot in the U.S. Air Force in World War II and awarded a medal of valor for his service. In 1947, at the request of Ben Gurion, he left his job as a flight engineer at TWA to recruit fellow airmen and buy planes for the Israeli Air Force-in-formation. He headed a vast aircraft smuggling operation, which included purchasing and refurbishing used aircraft, including U.S. military planes, which were flown to Israel via Florida and Czechoslovakia under the guise of a fictious Panamanian airline. Over 30 bombers and cargo planes were acquired in this manner. Schwimmer was nearly arrested several times before fleeing to Canada and then to Israel, where he continued to help the nascent Israeli Air Force during the War of Independence. Schwimmer – Ben Gurion said at the time – was the Diaspora’s single-most important contribution to the young state’s survival.

author Julie ZuckermanShortly after his return to the United States in 1949, Schwimmer and five others were tried and convicted of violating the Neutrality Act. The judge stripped Schwimmer of his voting rights and his veteran benefits and slapped him with a $10,000 fine, but he did not sentence him to any jail time. Schwimmer went on to move to Israel, where he founded Israel’s largest aerospace company. Though Schwimmer never asked for a pardon – he worried that a second Holocaust might be perpetrated should Israel lose the war—but President Bill Clinton granted him one in 2001.

author Julie ZuckermanShortly after his return to the United States in 1949, Schwimmer and five others were tried and convicted of violating the Neutrality Act. The judge stripped Schwimmer of his voting rights and his veteran benefits and slapped him with a $10,000 fine, but he did not sentence him to any jail time. Schwimmer went on to move to Israel, where he founded Israel’s largest aerospace company. Though Schwimmer never asked for a pardon – he worried that a second Holocaust might be perpetrated should Israel lose the war—but President Bill Clinton granted him one in 2001. A few months after I wrote the first draft “Clandestiny,” in which one of plotlines takes inspiration from Schwimmer’s story, he passed away on his 94th birthday. The full story of how American Jews like Schwimmer and my relatives helped the young Jewish state is too complex for the space allotted, though I remember thinking at the time of my research that if I should ever write a biography, I would be honored to write his. According to one obituary, Schwimmer resisted all appeals to write his memoir, asking, “Who would be interested?” From the small amount that I learned through my research, I can imagine many who would be.

~

Julie Zuckerman’s fiction and nonfiction have appeared in a variety of publications, including The SFWP Quarterly, The MacGuffin, Salt Hill, Sixfold, Crab Orchard Review, Ellipsis, The Coil, and others. The Book of Jeremiah, her debut novel-in-stories, was the runner-up in the 2018 Press 53 Award for Short Fiction, and is due in May 2019. A native of Connecticut, she resides in Modiin, Israel, with her husband and four children. Learn more at https://www.juliezuckerman.com/

Published on May 03, 2019 04:00

April 30, 2019

For medieval enthusiasts: 10 new and upcoming historical novels for 2019

Two months ago, in response to a post about historical novels set before the 20th century, I was chatting with another reader who lamented the small quantity of medieval-set fiction on offer. It's a favorite period of mine, too, going back to Anya Seton's classic novel Katherine, which I'd read for a 9th-grade English assignment. While the Middle Ages may not be a current trend (and rarely has been), there are some recent and upcoming releases set during the period if you hunt for them. The ten novels below were published in the US, UK, and Ireland, by a variety of publishers: the Big Five, small presses, and independent authors. Most of them center on historical figures, some better known than others.

Part 2 of the life journey (after The Greenest Branch) of Hildegard of Bingen, an ambitious female physician, in 12th-century Germany. Iron Knight, Feb 2019. [see on Goodreads]

The background to the Kilkenny Witch Trial of 14th-century Ireland, and the relationship between two women: Alice Kytler and her servant, Petronelle. Penguin Ireland, April 2019. [see on Goodreads]

The famous love story between Heloise and Abelard in 1100s Paris, juxtaposed with the tale of a modern historical novelist writing about the couple. Sceptre, March 2019. [see on Goodreads]

First in a projected trilogy, this newest novel from Dunlap (who has written both adult and YA historical fiction) focuses on an orphaned brother and sister at the time of the Cathar heresy in medieval France. [see on Goodreads]

The third and final volume in Hartsuyker's rousing saga of Viking-era Norway. I'll be reading it next! Harper, Aug. 2019. [see on Goodreads]

The publicity material promises an intriguing, multi-layered mystery set in 15th-century Tuscany, beginning as a soldier looks into two murders. Allison & Busby, March 2019. [see on Goodreads]

Drama that examines the heart of the Robin Hood legend, and of legends themselves, set in the shire of Nottingham in 1191, while King Richard is off on Crusade. The Goodreads reviews so far are stellar. Forge, August 2019. [see on Goodreads]

Biographical fiction about Ailenor of Provence, the young, and later controversial, bride of Henry III of England in the mid-13th century. Accent Press, Sept. 2019. [see on Amazon UK: not on Goodreads yet.]

The latest medieval epic from O'Brien, who has written about women prominent in their time whose stories are little known today. Here her subject is Constance of York, granddaughter of Edward III. HQ, August 2019. [see on Goodreads]

Owen Archer, hero of Robb's long-running series, makes his return to the page in this new mystery set in 14th-century York. Here he investigates the death of a man supposedly killed by wolves. [see on Goodreads]

Part 2 of the life journey (after The Greenest Branch) of Hildegard of Bingen, an ambitious female physician, in 12th-century Germany. Iron Knight, Feb 2019. [see on Goodreads]

The background to the Kilkenny Witch Trial of 14th-century Ireland, and the relationship between two women: Alice Kytler and her servant, Petronelle. Penguin Ireland, April 2019. [see on Goodreads]

The famous love story between Heloise and Abelard in 1100s Paris, juxtaposed with the tale of a modern historical novelist writing about the couple. Sceptre, March 2019. [see on Goodreads]

First in a projected trilogy, this newest novel from Dunlap (who has written both adult and YA historical fiction) focuses on an orphaned brother and sister at the time of the Cathar heresy in medieval France. [see on Goodreads]

The third and final volume in Hartsuyker's rousing saga of Viking-era Norway. I'll be reading it next! Harper, Aug. 2019. [see on Goodreads]

The publicity material promises an intriguing, multi-layered mystery set in 15th-century Tuscany, beginning as a soldier looks into two murders. Allison & Busby, March 2019. [see on Goodreads]

Drama that examines the heart of the Robin Hood legend, and of legends themselves, set in the shire of Nottingham in 1191, while King Richard is off on Crusade. The Goodreads reviews so far are stellar. Forge, August 2019. [see on Goodreads]

Biographical fiction about Ailenor of Provence, the young, and later controversial, bride of Henry III of England in the mid-13th century. Accent Press, Sept. 2019. [see on Amazon UK: not on Goodreads yet.]

The latest medieval epic from O'Brien, who has written about women prominent in their time whose stories are little known today. Here her subject is Constance of York, granddaughter of Edward III. HQ, August 2019. [see on Goodreads]

Owen Archer, hero of Robb's long-running series, makes his return to the page in this new mystery set in 14th-century York. Here he investigates the death of a man supposedly killed by wolves. [see on Goodreads]

Published on April 30, 2019 15:00

April 26, 2019

The Old Drift by Namwali Serpell, a genre-defying epic of Zambian history

Proudly uncategorizable, Serpell’s excellent first novel traverses a shifting genre landscape while delving into Zambia’s tumultuous history in intimate detail.

Proudly uncategorizable, Serpell’s excellent first novel traverses a shifting genre landscape while delving into Zambia’s tumultuous history in intimate detail.The Old Drift is a settlement along the Zambezi River where the novel begins in the early twentieth century. It concludes in 2023, covering British colonialism, the Kariba Dam’s construction, Zambian independence, the AIDS epidemic, and more.

“To err is human, that’s your doom and delight,” pronounces the unusual swarm of creatures narrating the story, which emphasizes the circumstantial and genetic chances affecting one’s life. While a genealogical chart reveals people’s connections, the plot remains surprising.

The tale of Sibilla, a hirsute Italian woman, has fairy-tale echoes. Matha, a teenage girl, trains as an astronaut, while other characters play major roles in medical research. From the Shiwa Ng’andu estate to the Kalingalinga compound, the deeply human, ethnically diverse characters fall in love, grieve, betray one another, and make shocking choices.

In this smartly composed epic, magical realism and science fiction interweave with authentic history, and the “colour bar,” the importance of female education, and the consequences of technological change figure strongly. It’s also a unique immigration story showing how people from elsewhere are enfolded into the country’s fabric.

While a bit too lengthy, Serpell’s novel is absorbing, occasionally strange, and entrenched in Zambian culture—in all, an unforgettable original.

I read The Old Dtift last December and wrote this (starred) review for Booklist's Feb 1 issue. The Old Drift was published in March. It's nearly 600 pages long, an unusual and detailed novel not like anything I've read before! Originally from Zambia, the author is an English professor at the University of California-Berkeley.

Published on April 26, 2019 05:23

April 22, 2019

A royal Stuart scandal: The Poison Bed by Elizabeth Fremantle

How does one write a successful thriller about a well-known historical event, in which not only is the outcome known, but most characters once lived? This would seem an unusual challenge, but in The Poison Bed, Elizabeth Fremantle manages it by amping up the psychological tension and keeping readers in suspense about the true nature of her male and female leads.

How does one write a successful thriller about a well-known historical event, in which not only is the outcome known, but most characters once lived? This would seem an unusual challenge, but in The Poison Bed, Elizabeth Fremantle manages it by amping up the psychological tension and keeping readers in suspense about the true nature of her male and female leads.In the early 17th century, the so-called Overbury Affair agitated the royal court of James I of England. While named after its victim, a minor English poet who met an untimely end in 1613, the scandal surrounding his death spiraled out, two years later, to ensnare prominent personalities, staining the court’s image.

As it begins, the two people at the center, a married couple, sit in separate cells in the Tower of London awaiting trial for Thomas Overbury’s murder. Frances Howard, a noted beauty, tells her story to her baby’s wet-nurse, while her husband Robert Carr shares his own perspective of what happened. The ultimate question: which of them was responsible?

A member of the notorious Howard family, Frances had first been wed to the Earl of Essex, while Robert, the king’s favorite, could use a wife of his own to hide the truth about his own affair with King James. Engineering the annulment of Frances’s marriage and her subsequent union to Robert is her great-uncle, the Earl of Northampton, who has plans to tie his family close to royal power. The couple themselves feel a surprising attraction to one another, but Thomas Overbury, Robert’s good friend and former mentor, stands in his way, since he thinks Frances is an immoral whore (he’s blunt about it, too).

The atmosphere is dark and claustrophobic throughout, as conveyed in the psychologically confining environment, with its glimpses of violence and practitioners of black magic. Fremantle effectively depicts the venal sexual politics of early Jacobean England, with nearly everyone vying for their own preferment at the cost of others. Readers may look in vain for anyone to admire; pity may be the best that one can do. The two accounts, by Robert and Frances, run in unison early on, but differences in their stories creep in. A twist partway through turns their situation on its head.

Personally, I found their personalities so unpleasant, apart from the nursemaid Nelly and the Carrs’ innocent baby--who isn’t named--that I found myself closing the book from time to time as a form of mental escape. There’s no denying the effectiveness of Fremantle’s approach to this toxic historical scandal, though. It should appeal to those who enjoy The Girl on the Train-style thrillers.

The Poison Bed was published by Pegasus this month; in its UK edition, published by Michael Joseph, the author writes as E. C. Fremantle. Thanks to the publisher for sending me an ARC at my request.

Published on April 22, 2019 16:00

April 17, 2019

The Red Daughter by John Burnham Schwartz, a novel of Svetlana Alliluyeva, Stalin's only daughter

As in The Commoner (2008), modeled on Japan’s empress, Schwartz again demonstrates his adroitness at illustrating the troubled lives of high-profile twentieth-century women.

As in The Commoner (2008), modeled on Japan’s empress, Schwartz again demonstrates his adroitness at illustrating the troubled lives of high-profile twentieth-century women.His new subject is Svetlana Alliluyeva, Stalin’s daughter, whose defection to the U.S. in 1967 drew international attention and furor. Schwartz has a personal connection, since his lawyer father brought Alliluyeva to America under CIA cover, but his personality and role have been fictionalized.

In Schwartz’s variation, in private journals left to her former lawyer, Peter Horvath, Svetlana details her itinerant life, attempts to become Americanized, and feels guilt over abandoning her adult children, whom she had hoped to liberate from her past. An unlikely correspondence leads her to an Arizona-based group of Frank Lloyd Wright acolytes whose repressive commune, ruled by Wright’s widow, feels very Russian.

Strong-willed and needy, Svetlana grows close to Peter, straining his relationship with his wife. What she doesn’t reveal is also illuminating; we learn almost nothing of her earlier marriages.

A perceptive exploration of identity, motherhood, and how one woman valiantly tried to shed the heavy mantle of her father’s infamous legacy.

I reviewed The Red Daughter for the March 1 issue of Booklist, and the novel will be published by Random House on April 29th.

Published on April 17, 2019 04:39

April 10, 2019

Interview with Kris Waldherr, author of the Victorian gothic novel The Lost History of Dreams

Kris Waldherr's accomplished debut novel The Lost History of Dreams, set in Victorian times, is suffused with Gothic atmosphere while playing with genre tropes. In 1850, Robert Highstead, a post-mortem photographer, is asked to transport the remains of a distant cousin, noted poet Hugh de Bonne, to the stained glass chapel in Shropshire where Hugh's beloved wife, Ada, had been laid to rest years before. Ada's niece Isabelle, however, proves unwilling to unlock the chapel to fulfill Hugh's last wishes unless Robert listens to her account of the couple's tragic love story. Thus two intertwining storylines are unfurled, each heightening the experience of the other. Kris Waldherr is a talented visual artist, and her skills are reflected in the writing, with its subtle attention to detail and multilayered themes. Hope you'll enjoy this interview, as well as the novel!

Kris Waldherr's accomplished debut novel The Lost History of Dreams, set in Victorian times, is suffused with Gothic atmosphere while playing with genre tropes. In 1850, Robert Highstead, a post-mortem photographer, is asked to transport the remains of a distant cousin, noted poet Hugh de Bonne, to the stained glass chapel in Shropshire where Hugh's beloved wife, Ada, had been laid to rest years before. Ada's niece Isabelle, however, proves unwilling to unlock the chapel to fulfill Hugh's last wishes unless Robert listens to her account of the couple's tragic love story. Thus two intertwining storylines are unfurled, each heightening the experience of the other. Kris Waldherr is a talented visual artist, and her skills are reflected in the writing, with its subtle attention to detail and multilayered themes. Hope you'll enjoy this interview, as well as the novel!~

I love the Gothic themes and haunted Victorian atmosphere of The Lost History of Dreams. Where does your interest in Gothic literature originate?

It’s hard to recall ever not being fascinated by the Gothic—I was that precocious kid sneaking into the adult section of the library. I’d read the nineteenth century greats, like the Brontes and Victor Hugo, as well as contemporary authors such as Victoria Holt and Daphne du Maurier. Growing up in suburban New Jersey, I yearned for a life on the moors where I’d live in an old house crammed with secrets and ghosts. I was obsessed with the sheer romanticism of it all, especially if there were ghosts involved. The irony is I now live in an old house that’s had its share of ghostly visitations. In particular, there’s a spot on the stairway that seems to be a draw. Members of my family have caught glimpses of shadowy figures there—even our cat seems to sense something. That written, the longer we’ve lived in this house, the quieter they’ve become.

Isabelle tells Robert that while the public venerates Hugh and his poetry, “no one knows about Ada” – and she later reveals the details of a life that’s been hidden from view. It all reads smoothly, but how challenging was this story-within-a-story approach to conceptualize and write?

I’m glad the story-within-a-story reads smoothly because it was incredibly tricky to write! I especially struggled to keep one story from overpowering the other—I spent a lot of time editing for this alone!

I knew from the beginning I wanted The Lost History of Dreams to have a nested story structure akin to novels such as The Thirteenth Tale and Possession. But how to go about writing it? After several experiments, I ended up writing each storyline separately, then combining them into one document using Scrivener. One storyline is written in a close third person, the second in a more omniscient point of view that occasionally breaks the fourth wall. On top of that, I included letters and poems, which were intended to add another layer of commentary, if you will. Finally, I revised the novel for pacing, plot, and tension—I needed to have each storyline hand off to each other in a way that felt organic. I also made a spreadsheet diagramming the the two timelines, to keep all the details straight. When I printed out the spreadsheet, it filled the length of my large worktable!

I was also curious if Ada’s character was modeled on anyone from history. Are there any historical women, muses or partners to their more famous 19th-century husbands, that you feel deserve to be better known?

Ada wasn’t modeled directly on anyone, though her character was definitely informed by Gothic tropes, primarily the one of the orphaned heiress at risk. That written, I couldn’t resist giving Ada the same first name as Ada Lovecraft, Lord Byron’s brilliant mathematician daughter—the name was a wink at Hugh’s Byronesque qualities. As for historical women who deserve to be better known, there are so many! If we’re talking nineteenth century muses and wives, off the top of my head I’d love more people to learn about Elizabeth Siddal’s poetry and paintings, and Jane Morris’s brilliance as a needlewoman. Both remain better known as Pre-Raphaelite adjuncts to Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Morris than they do as artists in their own right.

Where did you come across the concept of eye portraits and then decide to include them in the novel?

Eye portraits, aka Lover’s Eye jewelry, were fashionable in the 17th and 18th centuries with couples having secret affairs. It was a way to wear a physical representation of your beloved while keeping your involvement on the low down—most people can’t identify who someone is from only an eye. I first learned of eye portraits from an exhibition catalogue a friend had out on her coffee table. I was instantly intrigued by their beauty and history, and knew I had to somehow work them into The Lost History of Dreams. I hadn’t expected an eye portrait to end up on my book cover as a design element, but I’m delighted it did!

During your research trips to England, were there any facts or topics you learned about that you might not have discovered otherwise?

For me, research travel is an essential part of my creative process. I can’t really write in depth until I’ve personally experienced the landscape and architecture surrounding my characters. I especially love walking in their footsteps, getting those sense memories.I was glad to visit Herne Bay, a seaside resort Ada and Hugh visit during their courtship. I’d assumed Herne Bay had a sand beach, but turns out it’s quite rocky—very different from what I’d envisioned even after studying period photographs. I was also surprised by how the water seemed less oceanic than I’d thought, and how close various landmarks were to each other. Herne Bay wasn’t very glamorous, to be honest—more like the Jersey shore than the Cote d’Azur.

One aspect I found especially memorable was the beauty and mystery of the chapel called “Ada’s Folly,” especially the stained-glass windows. How did you come up with the design of the chapel?

Strangely enough, the initial inspiration for Ada’s Folly was a newspaper article about a Paris apartment that hadn’t been opened in seventy years. For some reason, this led to my imagining a glass chapel in the woods that had been locked since its creation; I wondered what might be found inside. From there, I read about Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill and other architectural follies. In terms of the design for Ada’s Folly, I was inspired by a photograph of an abandoned chapel in a French forest taken by Romain Veillon; the photograph served as my computer desktop while I wrote Lost History. I also read about neo-Gothic stained glass of the nineteenth century and the history of French stained glass after the Revolution, which is a fascinating story onto itself.

What do you enjoy most about writing historical fiction?

I love the world building that’s involved in writing historical fiction, how richly immersive can be. Though I’m fascinated by all the details, I’m especially intrigued by how history influences character and visa versa. I also love exploring the social constraints of a period, which spurs ideas for plot and character. Sometimes when I’ve finished work for the day, it’s a shock to turn from the nineteenth century back to contemporary Brooklyn!

~

The Lost History of Dreams by Kris Waldherr (Atria; April 9, 2019), is a story about a post-mortem photographer who unearths dark secrets of the past that may hold the key to his future, in the gothic tradition of Wuthering Heights and The Thirteenth Tale. Waldherr effortlessly spins a sweeping, atmospheric gothic mystery about love and loss that blurs the line between the past and the present, truth and fiction, and life and death.

Kris Waldherr is an award-winning author, illustrator, and designer. She is a member of the Historical Novel Society, and her fiction has been awarded with fellowships by the Virginia Center of the Creative Arts and a reading grant by Poets & Writers. Kris Waldherr works and lives in Brooklyn in a Victorian-era house with her husband, the anthropologist-curator Thomas Ross Miller, and their young daughter. Visit her website at http://www.kriswaldherrbooks.com.

Published on April 10, 2019 04:00

April 8, 2019

Interview with Edith Maxwell, author of Charity's Burden, a Quaker Midwife mystery set in 1889 Massachusetts

Edith Maxwell is an Agatha-nominated mystery writer with several current series, both contemporary and historical. Charity's Burden, published this week by Midnight Ink, is her latest entry in the Quaker Midwife mysteries; it takes place in Amesbury, Massachusetts, in the winter of 1889. Like the author herself, midwife and sleuth Rose Carroll is a member of the Society of Friends. In this book, Rose looks into the suspicious death of a young mother, perhaps from an illegal abortion. If you'd enjoy spending time in historical small-town New England in the company of a compassionate woman, while picking up details on female health care and Quaker beliefs and practices at the time, this novel is worth investigating. Let me add one more thing that attracted me to the story: the heroine wears spectacles! I was glad to get the opportunity to ask the author a few questions.

~

Although it’s the fourth in a series, Charity’s Burden stands well on its own. What do you particularly enjoy about writing historical mysteries in a series, and what are the challenges?

Although it’s the fourth in a series, Charity’s Burden stands well on its own. What do you particularly enjoy about writing historical mysteries in a series, and what are the challenges?

Thank you! I always try to make the books accessible to those who haven’t read the preceding installments. In every book, I address a different issue of the times, which entails a new set of research questions. As with my contemporary series, the cast of core actors stays constant but new characters emerge, in the service of the story as well as of the theme of that book. In this book, Madame Restante and Doctor Wallace are both unique to the issue of birth control in 1889.

I liked Rose a lot. She’s a young, single woman with a gentle outward demeanor, but she can be very direct, and she doesn’t take nonsense from anyone. How did you develop her personality?

I am so pleased you like her. I do, too. I based her quiet demeanor and physical traits (tall, dark haired, slim) on a midwife who helped with my first son’s birth thirty-two years ago. Her personality evolved in Delivering the Truth, the first book in the series, and continues to. I want her to be forthright and courageous even as she’s a good listener and caregiver. Above all, she doesn’t abide injustice.

I appreciated all the detail on women’s health care and contraception in late 19th-century America, from techniques for “family spacing” to the subtly coded messaging in newspaper ads to the dangers of “mechanical abortion” at the time. How did you research this? Were there any interesting or surprising things you discovered that you weren’t able to include?

I read Contraception and Abortion in Nineteenth Century America by Janet Farrell Brodie and took lots of notes. I also read My Notorious Life by Kate Manning, a novel based on the life of Madame Restell, a nineteenth-century midwife and provider of abortions in New York City. She was the inspiration for my Madame Restante. I had not known of the highly restrictive Comstock Laws before I researched Charity’s Burden, laws which made even talking about preventing pregnancy a federal crime. I know many details I learned didn’t get into the book, but I was glad I could include a mention of the “water cure” method of avoiding pregnancy. Not sure how effective that one was.

What has the experience been like in setting a historical mystery in the town where you live? Are there geographic aspects of Amesbury that haven’t changed much over the past century and more?

I love living in Amesbury, a city full of history, and walking the streets every day. I imagine setting scenes in the brick mill building near Rose’s house (which is my own home), on Main Street near Pattens Pond, or in front of an impressive mansard-roof house. I own digital versions of aerial maps drawn in 1880 and 1890, which come with churches, public buildings, businesses, and even homes labeled by name. I can zoom in and check whether a particular edifice was built by 1890, what certain places looked like, and where a hospital or school was located. I’ve used real business names in the books.

The Powow River flows right through Amesbury and drops about 90 feet in elevation over a quarter mile, making it a perfect place to harness water energy over the last few centuries. Some of the earlier millraces are gone, but nearly all of the original tall brick mill buildings remain downtown, repurposed into shops, restaurants, yoga studios, and offices. The Powow eventually drains into the wide Merrimack River. The Lowell Boat Shop on the Merrimack has been operating continually since the 1600s, making sturdy and graceful dories.

Can you tell I love my town and the setting for the Quaker Midwife Mysteries? I’m delighted Quaker Midwife Mystery #4 is out, and I am happy to announce the series is moving over to Beyond the Page Publishing. Look for Judge Thee Not to release this fall! There will be at least two more in the series after that.

Good news - thanks very much for taking the time to answer my questions!

~

Book blurb: When Charity Skells dies in winter of 1889 from an apparent early miscarriage, Quaker midwife Rose Carroll wonders about the copious amount of blood. She learns Charity’s husband appears to be up to no good with a young woman, a mysterious Madame Restante appears to offer illegal abortions and herbal birth control, and a disgraced physician in town does the same. Rose once again works with police detective Kevin Donovan to solve the case before another life is taken.

Book blurb: When Charity Skells dies in winter of 1889 from an apparent early miscarriage, Quaker midwife Rose Carroll wonders about the copious amount of blood. She learns Charity’s husband appears to be up to no good with a young woman, a mysterious Madame Restante appears to offer illegal abortions and herbal birth control, and a disgraced physician in town does the same. Rose once again works with police detective Kevin Donovan to solve the case before another life is taken.

Bio: Edith Maxwell writes the Quaker Midwife Mysteries, the Local Foods Mysteries, and award-winning short crime fiction. As Maddie Day she writes the Country Store Mysteries and the Cozy Capers Book Group Mysteries. Maxwell, with seventeen novels in print and four more completed, has been nominated for an Agatha Award six times. She lives north of Boston with her beau and two elderly cats, and gardens and cooks when she isn’t killing people on the page or wasting time on Facebook. Please find her at edithmaxwell.com, on Instagram, and at the Wicked Authors blog.

~

Although it’s the fourth in a series, Charity’s Burden stands well on its own. What do you particularly enjoy about writing historical mysteries in a series, and what are the challenges?

Although it’s the fourth in a series, Charity’s Burden stands well on its own. What do you particularly enjoy about writing historical mysteries in a series, and what are the challenges? Thank you! I always try to make the books accessible to those who haven’t read the preceding installments. In every book, I address a different issue of the times, which entails a new set of research questions. As with my contemporary series, the cast of core actors stays constant but new characters emerge, in the service of the story as well as of the theme of that book. In this book, Madame Restante and Doctor Wallace are both unique to the issue of birth control in 1889.

I liked Rose a lot. She’s a young, single woman with a gentle outward demeanor, but she can be very direct, and she doesn’t take nonsense from anyone. How did you develop her personality?

I am so pleased you like her. I do, too. I based her quiet demeanor and physical traits (tall, dark haired, slim) on a midwife who helped with my first son’s birth thirty-two years ago. Her personality evolved in Delivering the Truth, the first book in the series, and continues to. I want her to be forthright and courageous even as she’s a good listener and caregiver. Above all, she doesn’t abide injustice.

I appreciated all the detail on women’s health care and contraception in late 19th-century America, from techniques for “family spacing” to the subtly coded messaging in newspaper ads to the dangers of “mechanical abortion” at the time. How did you research this? Were there any interesting or surprising things you discovered that you weren’t able to include?

I read Contraception and Abortion in Nineteenth Century America by Janet Farrell Brodie and took lots of notes. I also read My Notorious Life by Kate Manning, a novel based on the life of Madame Restell, a nineteenth-century midwife and provider of abortions in New York City. She was the inspiration for my Madame Restante. I had not known of the highly restrictive Comstock Laws before I researched Charity’s Burden, laws which made even talking about preventing pregnancy a federal crime. I know many details I learned didn’t get into the book, but I was glad I could include a mention of the “water cure” method of avoiding pregnancy. Not sure how effective that one was.

What has the experience been like in setting a historical mystery in the town where you live? Are there geographic aspects of Amesbury that haven’t changed much over the past century and more?

I love living in Amesbury, a city full of history, and walking the streets every day. I imagine setting scenes in the brick mill building near Rose’s house (which is my own home), on Main Street near Pattens Pond, or in front of an impressive mansard-roof house. I own digital versions of aerial maps drawn in 1880 and 1890, which come with churches, public buildings, businesses, and even homes labeled by name. I can zoom in and check whether a particular edifice was built by 1890, what certain places looked like, and where a hospital or school was located. I’ve used real business names in the books.

The Powow River flows right through Amesbury and drops about 90 feet in elevation over a quarter mile, making it a perfect place to harness water energy over the last few centuries. Some of the earlier millraces are gone, but nearly all of the original tall brick mill buildings remain downtown, repurposed into shops, restaurants, yoga studios, and offices. The Powow eventually drains into the wide Merrimack River. The Lowell Boat Shop on the Merrimack has been operating continually since the 1600s, making sturdy and graceful dories.

Can you tell I love my town and the setting for the Quaker Midwife Mysteries? I’m delighted Quaker Midwife Mystery #4 is out, and I am happy to announce the series is moving over to Beyond the Page Publishing. Look for Judge Thee Not to release this fall! There will be at least two more in the series after that.

Good news - thanks very much for taking the time to answer my questions!

~

Book blurb: When Charity Skells dies in winter of 1889 from an apparent early miscarriage, Quaker midwife Rose Carroll wonders about the copious amount of blood. She learns Charity’s husband appears to be up to no good with a young woman, a mysterious Madame Restante appears to offer illegal abortions and herbal birth control, and a disgraced physician in town does the same. Rose once again works with police detective Kevin Donovan to solve the case before another life is taken.

Book blurb: When Charity Skells dies in winter of 1889 from an apparent early miscarriage, Quaker midwife Rose Carroll wonders about the copious amount of blood. She learns Charity’s husband appears to be up to no good with a young woman, a mysterious Madame Restante appears to offer illegal abortions and herbal birth control, and a disgraced physician in town does the same. Rose once again works with police detective Kevin Donovan to solve the case before another life is taken.Bio: Edith Maxwell writes the Quaker Midwife Mysteries, the Local Foods Mysteries, and award-winning short crime fiction. As Maddie Day she writes the Country Store Mysteries and the Cozy Capers Book Group Mysteries. Maxwell, with seventeen novels in print and four more completed, has been nominated for an Agatha Award six times. She lives north of Boston with her beau and two elderly cats, and gardens and cooks when she isn’t killing people on the page or wasting time on Facebook. Please find her at edithmaxwell.com, on Instagram, and at the Wicked Authors blog.

Published on April 08, 2019 04:00

April 3, 2019

An uncommon 19th-century marriage: Thomas and Beal in the Midi by Christopher Tilghman

Third in his acclaimed Mason saga, Tilghman’s (The Right-Hand Shore, 2012) beautifully contemplative novel observes his protagonists’ uncommon marriage, showing how each must come into his and her own separately before they can flourish as a couple.

Third in his acclaimed Mason saga, Tilghman’s (The Right-Hand Shore, 2012) beautifully contemplative novel observes his protagonists’ uncommon marriage, showing how each must come into his and her own separately before they can flourish as a couple.In 1892, since their union is frowned upon in Maryland, Thomas Bayly and his African American bride, Beal, arrive in France to begin a new life together, leaving behind their disapproving families and his substantial inheritance.

Amid Paris’s upper-class art crowd, the sheltered, 19-year-old Beal attracts rival portraitists and the romantic advances of a Senegalese diplomat, while Thomas meets a comely Irish librarian while researching future prospects. He settles on winemaking and purchases an estate in the Languedoc, which obliges Beal to abandon her newly cosmopolitan lifestyle to follow him.

Alongside Beal and Thomas and their skillfully delineated journeys to maturity, many secondary characters also stand out, including a kindly nun and a difficult Jewish painter with unique insight into Beal’s state of mind. Belle Époque Paris and the southern French countryside are described exquisitely, as is the rich terroir that shapes the human heart.

Some notes:

Thomas and Beal in the Midi is published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux this week; I reviewed it for the 3/15/19 issue of Booklist. The other books in the Mason saga are Mason's Retreat (1996) and The Right-Hand Shore (2012), and I've only read the last two, but I believe they can be read in any order.

While this entry takes place in the 1890s, the first book is set much later, during the Great Depression, and The Right-Hand Shore takes place in both the 1920s, during the last years of Thomas's sister Mary, and the 1850s, during the youth of Mary, Thomas, Beal, and her brother. A focus on race and class, and a strong sense of place, permeates through each of the narratives, particularly the rural countryside of Maryland's eastern shore and France's Languedoc region, in addition to the art scene of 1890s Paris in this newest novel.

Published on April 03, 2019 07:00

March 30, 2019

The 2018 Langum Prize in American Historical Fiction - Winner and Finalist

The news recently arrived about the historical novels honored via the Langum Prize in American Historical Fiction, so without further ado...

Louisa Hall's Trinity (Ecco, 2018) is the winner of the 2018 Prize.

Louisa Hall's Trinity (Ecco, 2018) is the winner of the 2018 Prize.

From the press release: "The novel explores Robert Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb, through his interactions with seven imagined characters from 1943 to 1966. Speaking in 'testimonials,' the characters concentrate more on their own lives despite the major world events unfolding around them... Excellent historical fiction has the power to reveal emotional truths that history cannot, and Trinity does just that through its ingenious form and compelling prose."

And the finalist for 2018 is The Verdun Affair by Nick Dybek (Scribner, 2018).

From the press release: "Set in Verdun, France and Bologna, Italy in the aftermath of World War I (with a small portion in 1950s Hollywood, California), the chief protagonists are American. A young man works gathering up bones from the former Verdun battlefield for an ossuary when a young woman arrives in search of information about her husband who was reported missing in action... The book is well-written and a page turner. It has numerous elements of interest: a tender affair, the entry of a competing male, a dreadful description of Verdun following the battle, the mysterious amnesiac and the efforts to restore his memory or otherwise identify him, the chaos in Bologna incident to the early years of the Mussolini movement, and the pervasive effects of a significant mistruth spoken by one of the principal characters.

From the press release: "Set in Verdun, France and Bologna, Italy in the aftermath of World War I (with a small portion in 1950s Hollywood, California), the chief protagonists are American. A young man works gathering up bones from the former Verdun battlefield for an ossuary when a young woman arrives in search of information about her husband who was reported missing in action... The book is well-written and a page turner. It has numerous elements of interest: a tender affair, the entry of a competing male, a dreadful description of Verdun following the battle, the mysterious amnesiac and the efforts to restore his memory or otherwise identify him, the chaos in Bologna incident to the early years of the Mussolini movement, and the pervasive effects of a significant mistruth spoken by one of the principal characters.

Congratulations to both authors. I haven't read either book yet, but am looking forward to it!

The Langum Prize celebrates the "best book in American historical fiction that is both excellent fiction and excellent history." For more information, please see the Langum Charitable Trust website.

Louisa Hall's Trinity (Ecco, 2018) is the winner of the 2018 Prize.

Louisa Hall's Trinity (Ecco, 2018) is the winner of the 2018 Prize. From the press release: "The novel explores Robert Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb, through his interactions with seven imagined characters from 1943 to 1966. Speaking in 'testimonials,' the characters concentrate more on their own lives despite the major world events unfolding around them... Excellent historical fiction has the power to reveal emotional truths that history cannot, and Trinity does just that through its ingenious form and compelling prose."

And the finalist for 2018 is The Verdun Affair by Nick Dybek (Scribner, 2018).

From the press release: "Set in Verdun, France and Bologna, Italy in the aftermath of World War I (with a small portion in 1950s Hollywood, California), the chief protagonists are American. A young man works gathering up bones from the former Verdun battlefield for an ossuary when a young woman arrives in search of information about her husband who was reported missing in action... The book is well-written and a page turner. It has numerous elements of interest: a tender affair, the entry of a competing male, a dreadful description of Verdun following the battle, the mysterious amnesiac and the efforts to restore his memory or otherwise identify him, the chaos in Bologna incident to the early years of the Mussolini movement, and the pervasive effects of a significant mistruth spoken by one of the principal characters.

From the press release: "Set in Verdun, France and Bologna, Italy in the aftermath of World War I (with a small portion in 1950s Hollywood, California), the chief protagonists are American. A young man works gathering up bones from the former Verdun battlefield for an ossuary when a young woman arrives in search of information about her husband who was reported missing in action... The book is well-written and a page turner. It has numerous elements of interest: a tender affair, the entry of a competing male, a dreadful description of Verdun following the battle, the mysterious amnesiac and the efforts to restore his memory or otherwise identify him, the chaos in Bologna incident to the early years of the Mussolini movement, and the pervasive effects of a significant mistruth spoken by one of the principal characters.Congratulations to both authors. I haven't read either book yet, but am looking forward to it!

The Langum Prize celebrates the "best book in American historical fiction that is both excellent fiction and excellent history." For more information, please see the Langum Charitable Trust website.

Published on March 30, 2019 16:06