Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 49

September 26, 2019

Call Your Daughter Home by Deb Spera, 1920s-set fiction about three distinctive Southern women

Spera’s debut novel brims with grim authenticity as she recounts the unexpected bond between three women in the small town of Branchville, South Carolina. Her own great-grandmother and grandmother came from this same place, enduring grinding poverty while raising their families as best they could, and her deep familiarity with the land and people seeps into the pages.

Spera’s debut novel brims with grim authenticity as she recounts the unexpected bond between three women in the small town of Branchville, South Carolina. Her own great-grandmother and grandmother came from this same place, enduring grinding poverty while raising their families as best they could, and her deep familiarity with the land and people seeps into the pages. In 1924, five years before the Great Depression’s official start, hard times have already hit. The boll weevil infestation has devastated local cotton production, and the region hasn’t recovered. Married at thirteen, Gertrude (Gert) Pardee has an abusive alcoholic husband, four growing daughters, and no money to properly feed or clothe them. When she sees a dark way out, she takes it and doesn’t look back. When Gert arrives at the home of Mrs. Annie Coles to ask about a job and a place to live, she speaks first with the Coles’s black maid, Oretta (Retta) Bootles, and their three lives converge.

Their voices are unique and distinctive, and their personalities transcend what seem at first to be stereotypical roles. Gert sees the Missus a “fine old lady” whose house is “pure white and grand as the entrance to heaven,” but something terrible is clearly eating the Coles family from the inside. Annie is seventy, with two sons who struggle to emerge from under their father’s controlling thumb, two estranged daughters, and a beloved son who committed suicide years ago (she doesn’t know the reason). Her voice and painful journey are sadly believable. Retta, the middle-aged daughter of former slaves, is rough-edged but compassionate; she runs Miss Annie’s house while going home each night to her husband in their black neighborhood, “Shake Rag.” Their plot arcs aren’t equally satisfying (it would be a spoiler to say why), but the novel succeeds in evoking Southern women’s survival during tough times.

Call Your Daughter Home was published by Park Row/HarperCollins; I read it from a NetGalley copy.

Published on September 26, 2019 03:52

September 19, 2019

Bits and pieces of historical fiction news: critical reviews, bio-fiction, HF for new readers and WWII

Here's a roundup of historical fiction articles I found on the web recently.

Negative reviews can be dismaying for authors, but they can hold value for readers trying to decide whether a novel is worth their time. Sometimes I'll read a critical review that persuades me to read a book, and the review of Philippa Gregory's Tidelands in Entertainment Weekly did this for me. In contrast to the reviewer (staff journalist Maureen Lee Lenker), I'd grown steadily more lukewarm about Gregory's Tudor series and didn't read the last two, figuring I'd had my fill of Tudor drama and angst. I'm predicting that a novel that avoids juicy subplots in favor of something less obvious, more of a "slow burn" in other words, may be more to my taste. The comment about Gregory's handling of an "icky" abortion subplot (no spoilers if you've read it, please!) concerns me a bit, but the observation that this situation isn't handled in a way that echoes modern politics does not, since this is a novel set in the 17th century. I'll be reading Tidelands soon and will post my review then. For more background to Gregory's writing choices, she did a separate interview with EW about it.

Negative reviews can be dismaying for authors, but they can hold value for readers trying to decide whether a novel is worth their time. Sometimes I'll read a critical review that persuades me to read a book, and the review of Philippa Gregory's Tidelands in Entertainment Weekly did this for me. In contrast to the reviewer (staff journalist Maureen Lee Lenker), I'd grown steadily more lukewarm about Gregory's Tudor series and didn't read the last two, figuring I'd had my fill of Tudor drama and angst. I'm predicting that a novel that avoids juicy subplots in favor of something less obvious, more of a "slow burn" in other words, may be more to my taste. The comment about Gregory's handling of an "icky" abortion subplot (no spoilers if you've read it, please!) concerns me a bit, but the observation that this situation isn't handled in a way that echoes modern politics does not, since this is a novel set in the 17th century. I'll be reading Tidelands soon and will post my review then. For more background to Gregory's writing choices, she did a separate interview with EW about it.

For the History News Network, novelist Gill Paul discusses writing fiction about real people: the motivations, pitfalls, techniques, and occasional surprises (like if a person upon whom you've based a character reads your book and emails you). I liked this comment: "The best novels about real people make us re-evaluate the subject and perhaps alter our preconceived ideas."

For the History News Network, novelist Gill Paul discusses writing fiction about real people: the motivations, pitfalls, techniques, and occasional surprises (like if a person upon whom you've based a character reads your book and emails you). I liked this comment: "The best novels about real people make us re-evaluate the subject and perhaps alter our preconceived ideas."

At Book Riot, Jeffrey Davis has an essay called 5 Historical Fiction Books to Read if You Don't Like Historical Fiction. For several years, I was a regular guest presenter in an English class examining the reading interests of adults, and historical fiction was a tough sell for most of those students, too. I always enjoy reading other takes on the genre and noted the author's realization that while WWII is the most popular setting, historical fiction encompasses a broader period than that one era. Check out the recommendations there of "gateway" books for newcomers to HF. A couple of them take place in the '80s -- that is, my high school and college years, which does seem like a distant place at times.

Continuing with this theme, writing for Parade Magazine, author Kristen Harmel (The Winemaker's Wife) analyzes why WWII Fiction Is So Hot Right Now, providing some good reasons and also some fiction recommendations. Among them, the ones I've read are Kate Quinn's The Huntress and Ann Mah's The Lost Vintage, both of which I recommend as well.

Negative reviews can be dismaying for authors, but they can hold value for readers trying to decide whether a novel is worth their time. Sometimes I'll read a critical review that persuades me to read a book, and the review of Philippa Gregory's Tidelands in Entertainment Weekly did this for me. In contrast to the reviewer (staff journalist Maureen Lee Lenker), I'd grown steadily more lukewarm about Gregory's Tudor series and didn't read the last two, figuring I'd had my fill of Tudor drama and angst. I'm predicting that a novel that avoids juicy subplots in favor of something less obvious, more of a "slow burn" in other words, may be more to my taste. The comment about Gregory's handling of an "icky" abortion subplot (no spoilers if you've read it, please!) concerns me a bit, but the observation that this situation isn't handled in a way that echoes modern politics does not, since this is a novel set in the 17th century. I'll be reading Tidelands soon and will post my review then. For more background to Gregory's writing choices, she did a separate interview with EW about it.

Negative reviews can be dismaying for authors, but they can hold value for readers trying to decide whether a novel is worth their time. Sometimes I'll read a critical review that persuades me to read a book, and the review of Philippa Gregory's Tidelands in Entertainment Weekly did this for me. In contrast to the reviewer (staff journalist Maureen Lee Lenker), I'd grown steadily more lukewarm about Gregory's Tudor series and didn't read the last two, figuring I'd had my fill of Tudor drama and angst. I'm predicting that a novel that avoids juicy subplots in favor of something less obvious, more of a "slow burn" in other words, may be more to my taste. The comment about Gregory's handling of an "icky" abortion subplot (no spoilers if you've read it, please!) concerns me a bit, but the observation that this situation isn't handled in a way that echoes modern politics does not, since this is a novel set in the 17th century. I'll be reading Tidelands soon and will post my review then. For more background to Gregory's writing choices, she did a separate interview with EW about it. For the History News Network, novelist Gill Paul discusses writing fiction about real people: the motivations, pitfalls, techniques, and occasional surprises (like if a person upon whom you've based a character reads your book and emails you). I liked this comment: "The best novels about real people make us re-evaluate the subject and perhaps alter our preconceived ideas."

For the History News Network, novelist Gill Paul discusses writing fiction about real people: the motivations, pitfalls, techniques, and occasional surprises (like if a person upon whom you've based a character reads your book and emails you). I liked this comment: "The best novels about real people make us re-evaluate the subject and perhaps alter our preconceived ideas."At Book Riot, Jeffrey Davis has an essay called 5 Historical Fiction Books to Read if You Don't Like Historical Fiction. For several years, I was a regular guest presenter in an English class examining the reading interests of adults, and historical fiction was a tough sell for most of those students, too. I always enjoy reading other takes on the genre and noted the author's realization that while WWII is the most popular setting, historical fiction encompasses a broader period than that one era. Check out the recommendations there of "gateway" books for newcomers to HF. A couple of them take place in the '80s -- that is, my high school and college years, which does seem like a distant place at times.

Continuing with this theme, writing for Parade Magazine, author Kristen Harmel (The Winemaker's Wife) analyzes why WWII Fiction Is So Hot Right Now, providing some good reasons and also some fiction recommendations. Among them, the ones I've read are Kate Quinn's The Huntress and Ann Mah's The Lost Vintage, both of which I recommend as well.

Published on September 19, 2019 05:00

September 17, 2019

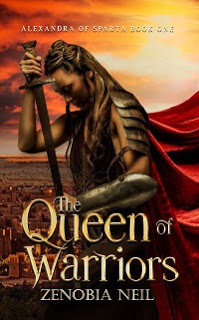

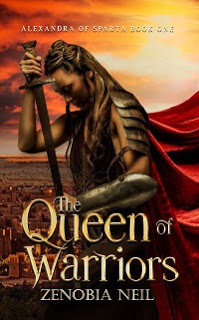

Diversity in the Ancient World, a guest post by Zenobia Neil, author of The Queen of Warriors

Author Zenobia Neil's newest historical novel, The Queen of Warriors, is published this Thursday, and today she's stopping by with a guest post about cultural diversity during the Hellenistic Period as part of her blog tour. Welcome, Zenobia!

~

Diversity in the Ancient WorldZenobia Neil

Alexander the Great represents many things to different people. When I first started researching the Hellenistic period while writing The Queen of Warriors, I was curious about ancient Persian perfume. I started reading a blog post about perfume in Hellenistic Persia. I learned that my main character Artaxerxes of Rhagae could indeed wear sandalwood and musk. And then I read the comment section, which quickly devolved into an argument between two strangers about if Alexander the Great was accursed or a hero.

Alexander the Great represents many things to different people. When I first started researching the Hellenistic period while writing The Queen of Warriors, I was curious about ancient Persian perfume. I started reading a blog post about perfume in Hellenistic Persia. I learned that my main character Artaxerxes of Rhagae could indeed wear sandalwood and musk. And then I read the comment section, which quickly devolved into an argument between two strangers about if Alexander the Great was accursed or a hero.

I think many figures in history can be both good and evil. No one is just one thing. All too often historical figures are taken out of context of their time and place. Enough books have been written about Alexander, and I have no interest in weighing in on his crimes and crowning glories. What fascinated me was the sheer intensity of feeling people still have about him. I want to talk about something else he did—or that he helped to do: by invading Persia and conquering basically all of Asia Minor and India, Alexander brought a flood of diversity throughout the land.

The Hellenistic Period (323 BCE - 31 BCE) saw a wave of cultural exchange. Alexander conquered Persia, but he also adopted Persian customs (despite the disapproval of his men). Greek culture, language, and art spread throughout Asia Minor, Egypt as far as Northeast Africa, and to part of modern India. (I should also stress that there wasn’t a unified Greece. Each polis or city-state had their own way of doing things, but I’m going to simplify and call Macedonians, Athenians, and Spartans “Greek.”)

When I first read about this time period in Mary Renault’s The Persian Boy, one of the aspects that interested me the most was the diversity of the people of this time period. Not only was I intrigued by the Persians—perceived as feminine by the Greeks because they wore leather trousers—but also by the Bactrians with their camel hair vests, and the Medes. I was enthralled by these ancient people I knew so little about.

Since I chose to write about a fictional Spartan woman warrior who becomes the leader of a mercenary army, I had characters from many different lands. Alexandra, the Queen of Warriors, has an army composed of Spartan commanders as well as Ionian, Nubian, and Median factions. Later in the book, her army adopts Persian squires.

Though I did not base my character on a known historical figure, we do know that Xenophon and his ten thousand were Greek soldiers in Persia, fighting for a Persian prince. Alexandra and her men find themselves in a similar position, fighting for a Macedonian king to keep Alexander’s tattered empire intact. In The Queen of Warriors, these diverse factions follow Alexandra for different reasons; one is her reputation as a fearless leader and the strength of her Spartan warriors.

Alexandra’s troop also includes Mithra, a Babylonian former concubine, a girl whose beauty has been its own curse. Mithra was raised in the pleasure houses of Babylon and has learned to become a warrior in her own way. When she’s given her freedom, she finds a place for herself in Alexandra’s household. Two other characters who sprang almost fully formed into the book are Silent Shadow, a Nubian marksman who lost his tongue when he refused to give away a secret, and Judah, a Judean slave who gains his freedom by risking his life.

The ancient world is often portrayed as one group of people battling another. Writing in the Hellenistic world gave me an opportunity to show the diversity and cultural exchange that existed thousands of years ago and continues to this day.

~

About the Author

Zenobia Neil was named after an ancient warrior queen who fought against the Romans. She writes about the mythic past and Greek and Roman gods having too much fun. She lives with her husband, two children, and dog in Los Angeles. The Queen of Warriors is her third book.

Zenobia Neil was named after an ancient warrior queen who fought against the Romans. She writes about the mythic past and Greek and Roman gods having too much fun. She lives with her husband, two children, and dog in Los Angeles. The Queen of Warriors is her third book.

Visit her at ZenobiaNeil.com. You can also follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

Giveaway

During the Blog Tour, we are giving away 2 eBooks and 2 paperbacks of the author's first two books, Psyche Unbound and The Jinni’s Last Wish! To enter, please use the Gleam form below.

Giveaway Rules:

– Giveaway ends at 11:59 pm EST on October 4th. You must be 18 or older to enter.

– Giveaway is open to the US only.

– Only one entry per household.

– All giveaway entrants agree to be honest and not cheat the systems; any suspicion of fraud will be decided upon by blog/site owner and the sponsor, and entrants may be disqualified at our discretion.

– The winner has 48 hours to claim prize or a new winner is chosen.

The Queen of Warriors

~

Diversity in the Ancient WorldZenobia Neil

Alexander the Great represents many things to different people. When I first started researching the Hellenistic period while writing The Queen of Warriors, I was curious about ancient Persian perfume. I started reading a blog post about perfume in Hellenistic Persia. I learned that my main character Artaxerxes of Rhagae could indeed wear sandalwood and musk. And then I read the comment section, which quickly devolved into an argument between two strangers about if Alexander the Great was accursed or a hero.

Alexander the Great represents many things to different people. When I first started researching the Hellenistic period while writing The Queen of Warriors, I was curious about ancient Persian perfume. I started reading a blog post about perfume in Hellenistic Persia. I learned that my main character Artaxerxes of Rhagae could indeed wear sandalwood and musk. And then I read the comment section, which quickly devolved into an argument between two strangers about if Alexander the Great was accursed or a hero.I think many figures in history can be both good and evil. No one is just one thing. All too often historical figures are taken out of context of their time and place. Enough books have been written about Alexander, and I have no interest in weighing in on his crimes and crowning glories. What fascinated me was the sheer intensity of feeling people still have about him. I want to talk about something else he did—or that he helped to do: by invading Persia and conquering basically all of Asia Minor and India, Alexander brought a flood of diversity throughout the land.

The Hellenistic Period (323 BCE - 31 BCE) saw a wave of cultural exchange. Alexander conquered Persia, but he also adopted Persian customs (despite the disapproval of his men). Greek culture, language, and art spread throughout Asia Minor, Egypt as far as Northeast Africa, and to part of modern India. (I should also stress that there wasn’t a unified Greece. Each polis or city-state had their own way of doing things, but I’m going to simplify and call Macedonians, Athenians, and Spartans “Greek.”)

When I first read about this time period in Mary Renault’s The Persian Boy, one of the aspects that interested me the most was the diversity of the people of this time period. Not only was I intrigued by the Persians—perceived as feminine by the Greeks because they wore leather trousers—but also by the Bactrians with their camel hair vests, and the Medes. I was enthralled by these ancient people I knew so little about.

Since I chose to write about a fictional Spartan woman warrior who becomes the leader of a mercenary army, I had characters from many different lands. Alexandra, the Queen of Warriors, has an army composed of Spartan commanders as well as Ionian, Nubian, and Median factions. Later in the book, her army adopts Persian squires.

Though I did not base my character on a known historical figure, we do know that Xenophon and his ten thousand were Greek soldiers in Persia, fighting for a Persian prince. Alexandra and her men find themselves in a similar position, fighting for a Macedonian king to keep Alexander’s tattered empire intact. In The Queen of Warriors, these diverse factions follow Alexandra for different reasons; one is her reputation as a fearless leader and the strength of her Spartan warriors.

Alexandra’s troop also includes Mithra, a Babylonian former concubine, a girl whose beauty has been its own curse. Mithra was raised in the pleasure houses of Babylon and has learned to become a warrior in her own way. When she’s given her freedom, she finds a place for herself in Alexandra’s household. Two other characters who sprang almost fully formed into the book are Silent Shadow, a Nubian marksman who lost his tongue when he refused to give away a secret, and Judah, a Judean slave who gains his freedom by risking his life.

The ancient world is often portrayed as one group of people battling another. Writing in the Hellenistic world gave me an opportunity to show the diversity and cultural exchange that existed thousands of years ago and continues to this day.

~

About the Author

Zenobia Neil was named after an ancient warrior queen who fought against the Romans. She writes about the mythic past and Greek and Roman gods having too much fun. She lives with her husband, two children, and dog in Los Angeles. The Queen of Warriors is her third book.

Zenobia Neil was named after an ancient warrior queen who fought against the Romans. She writes about the mythic past and Greek and Roman gods having too much fun. She lives with her husband, two children, and dog in Los Angeles. The Queen of Warriors is her third book. Visit her at ZenobiaNeil.com. You can also follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

Giveaway

During the Blog Tour, we are giving away 2 eBooks and 2 paperbacks of the author's first two books, Psyche Unbound and The Jinni’s Last Wish! To enter, please use the Gleam form below.

Giveaway Rules:

– Giveaway ends at 11:59 pm EST on October 4th. You must be 18 or older to enter.

– Giveaway is open to the US only.

– Only one entry per household.

– All giveaway entrants agree to be honest and not cheat the systems; any suspicion of fraud will be decided upon by blog/site owner and the sponsor, and entrants may be disqualified at our discretion.

– The winner has 48 hours to claim prize or a new winner is chosen.

The Queen of Warriors

Published on September 17, 2019 04:00

September 12, 2019

Kyung-Sook Shin's The Court Dancer, set in 19th-century Korea and Belle Époque Paris

For historical fiction fans interested in courtly intrigue but ready to move on from English and European locales, here’s a novel to consider. It should also attract literary fiction readers seeking a new perspective on France’s Belle Époque, or anyone who appreciates poetic writing and themes of cross-cultural identity.

For historical fiction fans interested in courtly intrigue but ready to move on from English and European locales, here’s a novel to consider. It should also attract literary fiction readers seeking a new perspective on France’s Belle Époque, or anyone who appreciates poetic writing and themes of cross-cultural identity. I’d purchased Kyung-Sook Shin’s The Court Dancer for the library’s bestseller collection a year ago after reading positive reviews but didn’t have time to read it myself until now. The fluid translation into English is by Anton Hur.

Based on a brief mention in a century-old diplomatic memoir, it fleshes out a tale set during a historical turning point. In 1876, the Jaemulpo Treaty (also called the Treaty of Ganghwa) between Japan and Korea ended Korea’s lengthy period of isolationism, after which many countries in the East and West began looking toward it, with an eye to diplomatic relations or foreign control.

Although not labeled as such, the novel's first chapter acts as a prologue that divides the rest of the novel into two halves: what happens before and after. In 1891, Yi Jin, a 22-year-old dancer at the Korean royal court, sails to France in the company of the man who loves her: Victor Collin de Plancy, the first French legate to Korea’s Joseon Kingdom. Although Jin holds affection for him and opens herself up by letting him brush her lustrous black hair (the story is full of symbolic actions such as these), it becomes clear she had little choice.

The Queen, who had acted as Jin’s surrogate mother, noticed the King’s growing attentions toward Jin and got him to send her away. This is a radical decision not only because of Jin’s and Victor’s unusual interracial relationship but also because agreeing to become a court dancer is itself a ritual as binding as a wedding ceremony. “Take care to live beautifully, so your name inspires a feeling of grace in the people who speak it,” the Queen tells her in farewell: eloquent but uninspiring words, since they address her behavior rather than personal happiness.

Throughout her life, Jin struggles to discover who she is, and in many indelible passages, Shin highlights her painfully illuminating journey from childhood on. A nameless orphan raised at the royal court, she forms an attachment to the lonely Queen Min and learns French from a visiting priest. While in Paris, Jin is accepted everywhere as Victor’s wife and draws applause for her inspired reading of Guy de Maupassant’s A Woman’s Life in the author’s presence. However, despite her fluent French and adoption of Western dress in a country that celebrates freedom, she attracts uncomfortable attention: feeling much like the Africans she sees in a dreadful Bois de Boulogne exhibit, put on display as an exoticized “other.” Victor collects Korean books and celadon pottery, and she grows troubled, imagining herself as another object.

“Jin could not be free of the attention of strangers, whether they were from kindness of curiosity. And without that freedom, there could be no equality.” Sometimes Shin lets readers soak up the symbolism in her beautiful imagery; other times, like here, she is effectively direct.

As a protagonist, Jin is hard to get to know. Her character feels opaque early on, and her physical appearance is highlighted (with multiple descriptions of the elegant nape of her neck, for example), but Shin gradually lets readers join her inner world. The author’s penchant for revealing a key plot point at a chapter’s beginning, then working her way backward to reveal how the situation happened, is a technique that some readers will find suspenseful, while others will find it frustrating. I found it some of both. That said, this melancholy novel about a courageous, misunderstood woman rewards those who stick with it.

The Court Dancer was published by Pegasus in 2018.

Published on September 12, 2019 05:24

September 9, 2019

Review of Elizabeth of Bohemia: A Novel about Elizabeth Stuart, the Winter Queen by David Elias

Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of James I of England, narrates her own story in Elias’s wide-ranging novel. Her life encompasses many seismic events, from the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, which was meant to kill her father and install her as a puppet queen for the Catholics, to the origins of the devastating Thirty Years’ War, followed by years of strain and exile in the Netherlands. In short, her dramatic story is ripe for fictional treatment. However, the result is an uneven gallop through 17th-century European history rather than a sweeping biographical epic of a strong-willed woman’s life.

Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of James I of England, narrates her own story in Elias’s wide-ranging novel. Her life encompasses many seismic events, from the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, which was meant to kill her father and install her as a puppet queen for the Catholics, to the origins of the devastating Thirty Years’ War, followed by years of strain and exile in the Netherlands. In short, her dramatic story is ripe for fictional treatment. However, the result is an uneven gallop through 17th-century European history rather than a sweeping biographical epic of a strong-willed woman’s life. The story begins as her father arranges her marriage to Frederick, Count Palatine of the Rhine, a Protestant prince of her own age. A young woman with a flair for the dramatic, Elizabeth is unrealistically upset with her parents for not letting her choose her own husband, and later causes a scene by kissing Frederick before a large crowd. The couple settles in Heidelberg; she later goads him into taking the crown of Bohemia and bears him thirteen children. Their short reign in Bohemia gives her the famous nickname of the “Winter Queen.”

Periods of overwrought emotion (she lusts after the English statesman and explorer incorrectly referred to many times as “Sir Raleigh”) alternate with more realistic, lively scenes and staid recitations of events. Elizabeth’s defining motive seems to be rebellion, and the era’s complicated political scene doesn’t come into clear view. Frederick is called a “Bohemian prince” years too early, and a strange subplot involving Elizabeth’s cousin, Arabella Stuart, serves no real purpose. The descriptions of fashion and décor are well done, however. Unfortunately, despite evocative period language and some truly moving moments as Elizabeth reflects on her family’s tragedies, readers interested in her life may not find this novel sufficiently satisfying.

Elizabeth of Bohemia was published by ECW Press (a Canadian small press) in June, and I'd reviewed it from NetGalley for the Historical Novels Review. This was a disappointing read, unfortunately. The later part of Elizabeth Stuart's life is well presented in Nicola Cornick's timeslip novel House of Shadows. She also appears in Jane Stevenson's The Winter Queen, which imagines a relationship between Elizabeth and an African prince.

Published on September 09, 2019 17:10

September 5, 2019

The Sweetest Fruits by Monique Truong, fiction about the women in Lafcadio Hearn's life

Three distinctive, remarkable women narrate Truong’s third novel. They never meet, but their lives are interconnected, and subtly influenced by one another’s, through one person they all love: Patrick Lafcadio Hearn, the Greek-born, Irish-raised writer and translator who became a talented journalist in mid-19th century America, and whose stories about his final home of Japan introduced Western audiences to his beloved adopted country.

Three distinctive, remarkable women narrate Truong’s third novel. They never meet, but their lives are interconnected, and subtly influenced by one another’s, through one person they all love: Patrick Lafcadio Hearn, the Greek-born, Irish-raised writer and translator who became a talented journalist in mid-19th century America, and whose stories about his final home of Japan introduced Western audiences to his beloved adopted country.He was a man created of continuous reinvention, and the journey he followed was so wide-ranging and unusual for its time that it’s hard to believe one 54-year life encapsulated it all. That said, it’s the women who shine here, and in a notable shift in perspective, Hearn comes alive only through their words. His absence from the page is frequently more palpable than his presence.

The first voice, expressed with lyricism and a mother’s yearning for her long-lost child, is that of Rosa Cassimati, a sheltered nobleman’s daughter from the Greek island of Cythera who was forced to leave her second son, Patricio, behind with his Anglo-Irish father’s family. Beginning in 1906, Alethea Foley, a formerly enslaved woman employed as a cook in a Cincinnati boardinghouse, remembers the boarder, Pat Hearn, who she admires and eventually marries—an event which has repercussions due to miscegenation laws. The longest tale belongs to Hearn’s second wife, Koizumi Setsu, a samurai’s daughter who bears him four children and sees his transformation from a foreign English teacher into a naturalized Japanese citizen.

Precisely researched, The Sweetest Fruits reads like a collection of oral histories; it provides a series of vivid impressions illuminating each heroine’s personal story and her purpose in telling it. While it may disappoint readers seeking an addictive plot, it resounds with character and feeling and has much to offer observers of historical women’s hidden lives.

The Sweetest Fruits was published this week by Viking in hardcover and ebook. I reviewed it from NetGalley for August's Historical Novels Review. You can read more about Truong's research and writing decisions in her interview with blogger Deborah Kalb, which I found linked from the author's website.

Published on September 05, 2019 16:25

August 31, 2019

The Summer Queen by Margaret Pemberton, a saga about Queen Victoria's royal grandchildren

British and European royalty buffs will revel in this book, in which the lives of Queen Victoria’s large clan of descendants are retold as a sweeping family saga. The action spans from a large gathering at Osborne House, the royal summer retreat, in 1879, through the fall of the Romanovs in 1918.

British and European royalty buffs will revel in this book, in which the lives of Queen Victoria’s large clan of descendants are retold as a sweeping family saga. The action spans from a large gathering at Osborne House, the royal summer retreat, in 1879, through the fall of the Romanovs in 1918.The principal viewpoints are May of Teck and her cousins Alicky of Hesse and Willy of Prussia—who, in later years, will be known respectively as Queen Mary, Empress Alexandra, and Kaiser Wilhelm. The story imagines that they form a pact that makes them kindred spirits, and the letters they exchange over the years (the women in particular) draw readers into their reflections, hopes, and fears.

Although all the characters are born to great privilege, Pemberton makes them relatable without ignoring their flaws. May, daughter of Victoria’s first cousin, grows up knowing that as a “Serene Highness”—a lesser pedigree than her royal relations—she can never aspire to marry the man she has a crush on: Eddy, the Prince of Wales’s heir. Although embarrassed by her parents’ financial problems, and their need to economize by moving to the Continent, May soaks up culture in Florence and returns to England a well-educated, level-headed young woman. Alicky, a shy, impressionable girl with a mystical bent, finds her soul mate in Nicky, the Romanov heir, but their religious differences seem insurmountable.

The plot emphasizes the personal over the political, with depictions of many courtships and attempted matches, from well-known pairings to the lesser-known and short-lived: like the scandalous second marriage of Alicky’s father, and the sexy affair between May’s brother and Maudie of Wales. Despite some instances of characters sharing facts for the reader’s benefit, it’s an addictive story, and Pemberton gets the relationships correct on their complicated family tree, too.

The Summer Queen was published by Pan this year in paperback. I reviewed it for August's Historical Novels Review from a personal copy. Margaret Pemberton is a former chair of Britain's Romantic Novelists' Association, and she's written under several pseudonyms. Her best known pen name in America is Rebecca Dean, under which she authored other novels with royal connections, like The Golden Prince (focusing on the young Edward VIII), and The Shadow Queen (about Wallis Simpson).

Published on August 31, 2019 07:10

August 28, 2019

'Tis 50 Years Since: 1969 in historical fiction

The Historical Novel Society's definition of historical fiction includes novels set at least 50 years before the writing, or those written by someone who wasn't alive at the time they were set. If you follow these guidelines, current novels taking place in 1969 are now considered historical fiction. So, for any readers who think the '60s are too recent to be "historical"... well, next year, the 1970s will start get included under that umbrella (!!).

The final year of the tumultuous 1960s saw a number of iconic events, including Woodstock, the moon landing, the continued Vietnam War, the Manson murders, Chappaquiddick, and the Stonewall riots. It's also the year I was born, so I'm soon to become historical myself. For that reason, I'm especially interested in historical fiction set in '69. These novels re-create the world I was born into but didn't personally experience.

Below are ten historical novels taking place during 1969 (including some published a year ago or more; this is cheating a bit). I'm looking forward to reading them.

And for further reading:: author Richard Sharp's guest post, The Sixties: The New Frontier in Historical Fiction, is one of my favorite essays on this site. It does a great job of putting in perspective why it's important for authors to continue examining the '60s and writing novels set back then.

Alcott covers events of the Cold War era (one plot strand takes place in '69) in her story of a couple, their brief affair, their son, and their involvement in major socio-cultural events. I love the cover design. Ecco, May 2019. [see on Goodreads]

A young Englishman attends American high school in '69 and gets caught up in many events of the day/year. Apippa, Oct. 2018. [see on Goodreads]

Searching for a place to belong, an impressionable California teenager gets drawn into the world of a dangerous cult during the summer of '69. Inspired by the Manson murders. Random House, 2016. [see on Goodreads]

The coming-of-age story of a nineteen-year-old woman, recipient of a military scholarship leading to a nursing career, who finds her future in limbo after awakening to the antiwar movement. She Writes, 2018. [see on Goodreads]

In this book described as the author's first historical novel, Hilderbrand presents the individual stories of the Levin siblings as they live through and experience pivotal events of that summer in Nantucket. Little, Brown, June 2019. [see on Goodreads]

The residents of a small Kentucky factory town face the aftermath of Vietnam when local soldiers' bodies return home, spurring seismic change in Cementville. Counterpoint, 2014. [see on Goodreads]

The NYT bestselling epic of the Vietnam War, written by a decorated veteran who served in combat as a Marine overseas and based his first novel on his own experiences. [see on Goodreads]

This top-selling print book for the first half of 2019, taking place in coastal North Carolina in 1969, is a story about a lonely young woman from the marshlands, her coming of age, the era's prejudices, and a mysterious murder. This one has been on my TBR since it came out. Putnam, 2018. [see on Goodreads]

Richardson's second novel takes place in the rural Kentucky mountains in 1969 and traces the coming of age of a young woman with big dreams. Kensington, 2016. [see on Goodreads]

The Woodstock music festival and the Vietnam draft figure in this autobiographical novel that's pitched as taking readers on a "psychedelically tinged trip of a lifetime." Candlewick, 2019. [see on Goodreads]

The final year of the tumultuous 1960s saw a number of iconic events, including Woodstock, the moon landing, the continued Vietnam War, the Manson murders, Chappaquiddick, and the Stonewall riots. It's also the year I was born, so I'm soon to become historical myself. For that reason, I'm especially interested in historical fiction set in '69. These novels re-create the world I was born into but didn't personally experience.

Below are ten historical novels taking place during 1969 (including some published a year ago or more; this is cheating a bit). I'm looking forward to reading them.

And for further reading:: author Richard Sharp's guest post, The Sixties: The New Frontier in Historical Fiction, is one of my favorite essays on this site. It does a great job of putting in perspective why it's important for authors to continue examining the '60s and writing novels set back then.

Alcott covers events of the Cold War era (one plot strand takes place in '69) in her story of a couple, their brief affair, their son, and their involvement in major socio-cultural events. I love the cover design. Ecco, May 2019. [see on Goodreads]

A young Englishman attends American high school in '69 and gets caught up in many events of the day/year. Apippa, Oct. 2018. [see on Goodreads]

Searching for a place to belong, an impressionable California teenager gets drawn into the world of a dangerous cult during the summer of '69. Inspired by the Manson murders. Random House, 2016. [see on Goodreads]

The coming-of-age story of a nineteen-year-old woman, recipient of a military scholarship leading to a nursing career, who finds her future in limbo after awakening to the antiwar movement. She Writes, 2018. [see on Goodreads]

In this book described as the author's first historical novel, Hilderbrand presents the individual stories of the Levin siblings as they live through and experience pivotal events of that summer in Nantucket. Little, Brown, June 2019. [see on Goodreads]

The residents of a small Kentucky factory town face the aftermath of Vietnam when local soldiers' bodies return home, spurring seismic change in Cementville. Counterpoint, 2014. [see on Goodreads]

The NYT bestselling epic of the Vietnam War, written by a decorated veteran who served in combat as a Marine overseas and based his first novel on his own experiences. [see on Goodreads]

This top-selling print book for the first half of 2019, taking place in coastal North Carolina in 1969, is a story about a lonely young woman from the marshlands, her coming of age, the era's prejudices, and a mysterious murder. This one has been on my TBR since it came out. Putnam, 2018. [see on Goodreads]

Richardson's second novel takes place in the rural Kentucky mountains in 1969 and traces the coming of age of a young woman with big dreams. Kensington, 2016. [see on Goodreads]

The Woodstock music festival and the Vietnam draft figure in this autobiographical novel that's pitched as taking readers on a "psychedelically tinged trip of a lifetime." Candlewick, 2019. [see on Goodreads]

Published on August 28, 2019 15:00

August 24, 2019

The Vexations by Caitlin Horrocks, fiction about composer Erik Satie and his family in the Belle Époque

A beautifully melancholic tone permeates this finely written debut novel from acclaimed short story author Horrocks. More than biographical fiction about French avant-garde composer Erik Satie (1866-1925), it’s a multi-perspective saga about the Satie siblings and their circle, and how their lives touched and diverged over decades.

A beautifully melancholic tone permeates this finely written debut novel from acclaimed short story author Horrocks. More than biographical fiction about French avant-garde composer Erik Satie (1866-1925), it’s a multi-perspective saga about the Satie siblings and their circle, and how their lives touched and diverged over decades.After their father abandons them in 1872, Eric (the original spelling), Louise, and Conrad live with their grandmother in Normandy, until Louise is later sent to stay with her great-uncle. The three never regain their childhood closeness. Now calling himself Erik, the composer pursues music in Paris, and struggles to rise above the cabaret scene, his erratic behavior giving him a “problematic level of fame.” Louise marries into a prominent family yet suffers significant losses.

Erik’s story looks beyond the “tortured genius” stereotype to something more nuanced and real, while both Louise and painter Suzanne Valadon, Erik’s one-time companion, personify different aspects of being a woman alone. The bleakness of the themes of loneliness, family separation, and thwarted expectations sits in counterpoise to several couples’ deep love and the creativity that produces innovative art.

The Vexations was published in August 2019 by Little, Brown; I'd reviewed it for Booklist's July issue. I confess I hadn't run across Erik Satie before picking up the novel and have since read that he's considerably more familiar a name in Europe than in the US. Louise, Erik's sister, is apparently so little-known that she isn't mentioned in Satie's Wikipedia entry; reading it, you'd think Conrad was his only sibling. I found her story the most poignant and was glad to discover it.

Published on August 24, 2019 06:08

August 18, 2019

The First Mrs. Rothschild by Sara Aharoni, fiction about the matriarch of a Jewish banking dynasty

With her third novel, a prizewinner in Israel, Sara Aharoni illuminates the matriarch of an international banking dynasty, perhaps the most famous in the world. When one thinks of the name Rothschild, visions of immense wealth, financial power, and influence come to mind, but their origins were humble. Aharoni shows how her heroine, a woman of remarkable character, retained her modest lifestyle through her near-century-long life and instilled strong values in her family.

With her third novel, a prizewinner in Israel, Sara Aharoni illuminates the matriarch of an international banking dynasty, perhaps the most famous in the world. When one thinks of the name Rothschild, visions of immense wealth, financial power, and influence come to mind, but their origins were humble. Aharoni shows how her heroine, a woman of remarkable character, retained her modest lifestyle through her near-century-long life and instilled strong values in her family. As a female historical-novel protagonist, Gutle Schnapper, nicknamed Gutaleh, is unusual since she’s content, and proud, to be the wife of a great man and the mother of his many children (five sons and five daughters that survived). Conditions in the Judengasse (Jewish quarter) of Frankfurt in 1770 are overcrowded, and its residents, forbidden from full citizenship, face tight restrictions on their movement, behavior, and careers. Meir Amschel Rothschild, well aware of these prejudices, determines to achieve dignity through financial success, and he finally wins Gutaleh’s father’s approval after becoming court banker to Wilhelm, crown prince of Hesse-Kassel.

In a voice that feels true to her culture, Gutaleh evokes her daily joys and laments, including her passionate marriage, her children’s births and deaths, and her periodic concerns (“Is it seemly to have our profits founded in war?” she wonders). While she remains at home in the Judengasse, running a growing household, Meir makes connections on his travels, overcoming countless obstacles while founding a large banking and trade empire.

The sections where Gutaleh shares details on international politics and economics are rather dry, but she’s an insightful observer of her children’s natures, particularly those of her sons. Each son later establishes his own financial institution in a different European city, creating an indomitable family network. Jewish history buffs will want to read this, and so will anyone seeking an original take on 18th- and 19th-century European history.

The First Mrs. Rothschild, translated into English by Yardenne Greenspan, was published by AmazonCrossing in 2019; I reviewed it from a NetGalley copy for the Historical Novels Review.

Did you know August is Women in Translation Month? This celebration was founded in 2014 by blogger Meytal Radzinski. Use the hashtag #WITMonth to locate other reviews, articles, interviews, and more on international women writers whose books were translated into English.

Published on August 18, 2019 13:16