Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 46

February 11, 2020

The Bermondsey Bookshop by Mary Gibson, an inspiring saga of working-class 1920s London

The Bermondsey Bookshop was a real place. During its nine-year existence (1921-30), the venue, under direction of the forward-thinking Ethel Gutman, provided working-class Londoners with literary and artistic sustenance through its reading room, author lectures, elocution lessons, drama readings, and other programming. Mary Gibson has taken this inspiring subject and woven it into a historical saga evoking an impoverished young woman’s dreams and struggles.

The Bermondsey Bookshop was a real place. During its nine-year existence (1921-30), the venue, under direction of the forward-thinking Ethel Gutman, provided working-class Londoners with literary and artistic sustenance through its reading room, author lectures, elocution lessons, drama readings, and other programming. Mary Gibson has taken this inspiring subject and woven it into a historical saga evoking an impoverished young woman’s dreams and struggles. Kate Goss grows up in a violent household in South London’s Bermondsey district in the 1920s. Raised by her harsh Aunt Sylvie since her Romany mother’s death and her father’s abandonment for parts unknown, she’s forced to leave school and begin work at a tin factory, where the camaraderie is warm but the pay meager and the work brutally hard on young bodies. After a vicious fight with her cousin and aunt, 17-year-old Kate is thrown out and left to depend on her own resources and pluck – and the latter she has in abundance. She takes multiple jobs, including one as a cleaner at a bookshop catering to local residents, one meant to be “common ground for the Mean Streets and the Mayfairs.” Throughout, she dreams about her father returning and lifting her away from her dreary life.

Kate is initially suspicious of the shop’s kindly proprietor, Ethel Gutman, who treats her with respect and asks to be called by her first name, as if they were equals. Through her bookshop role, Kate makes connections that prove important: Johnny Bacon, her former schoolgirl crush, a dockworker who contributes articles to the quarterly Bermondsey Book; Nora, a French teacher; and Martin North, a wealthy woman’s artist nephew. It’s clear that Johnny and Martin will develop into rivals for Kate’s affections. Both are rounded characters with visible flaws, making Kate’s decision complicated.

Gibson plunges readers deeply into the crushing poverty of Bermondsey’s streets through Kate’s hand-to-mouth existence, including the exhaustion of fourteen-hour days and the “Monday morning fever” that soldering girls got from breathing metal dust. Kate has admirable energy and courage that see her through hard times – there are many – though has a blind spot where her missing father is concerned. The novel also shows how difficult bridging social divides can be. At times I found myself wishing that the bookshop was more central to the storylines, and the novel's ending feels a bit fragmented. But I found myself fully involved in Kate’s refusal to admit defeat, and appreciative of the chance to learn more about an innovative historical bookshop and its social success.

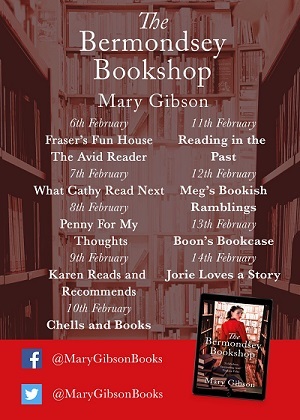

The Bermondsey Bookshop was published on 6 February by the UK publisher Head of Zeus. This review is the latest stop on the blog tour for the novel, and thanks to the publisher for approving me on NetGalley.

For more about the book: Amazon UK | Amazon US | Amazon Canada | Amazon Aus | Goodreads. Visit the author's website at marygibsonauthor.co.uk.

Published on February 11, 2020 04:00

February 10, 2020

Dreamland by Nancy Bilyeau, an opulent and dangerous trip to 1911 Coney Island

Peggy Batternberg is an American heiress, the granddaughter of a Jewish immigrant who made his fortune in mining. Tall, dark-haired, and elegant, she knows how to dress for the occasion and move in upper-crust Manhattan society in 1911. All her life, she’s been sheltered within her overprotective family, and her lack of experience with day-to-day practicalities (drawing her own bath, handling money) will make you shake your head. But she has gumption and a desire for self-improvement, which count for a lot.

Peggy Batternberg is an American heiress, the granddaughter of a Jewish immigrant who made his fortune in mining. Tall, dark-haired, and elegant, she knows how to dress for the occasion and move in upper-crust Manhattan society in 1911. All her life, she’s been sheltered within her overprotective family, and her lack of experience with day-to-day practicalities (drawing her own bath, handling money) will make you shake your head. But she has gumption and a desire for self-improvement, which count for a lot. Sadly for Peggy – but fortunately for readers of her entertaining narrative – she gets dragged away, reluctantly and literally, from her job as shopgirl at the Moonrise Bookstore and installed in Brooklyn’s posh Oriental Hotel on the Atlantic shoreline. Her family will be spending the summer there at the request of her younger sister Lydia’s rich fiancé, Henry Taul, whose mother supposedly wants to get to know them. Since Peggy and Lydia’s late father was a black sheep who died in debt, they need to do their utmost to ensure that Lydia’s marriage happens. Peggy’s past entanglement with Henry is conveniently never mentioned by her relatives.

The Oriental Hotel is close by Coney Island, called America’s Playground, which promises grand amusements and amazing sights, all new experiences for Peggy – one of which involves Stefan Chalakoski, a Serbian immigrant and artist with old world manners that surprise and delight her. He’s a dream of a character, his feelings and experienced worldview subtly expressed through his dialogue and actions. Midway through, Peggy even finds herself drinking Coca-Cola and enjoying it, to her family’s embarrassment. The plot delves into much more than her coming-of-age summer, though.

The prologue, the only part of the novel not in Peggy’s lively voice, depicts a chilling scene – a woman’s beachfront murder – and gets readers noticing the dark undercurrents threaded through her story. Other bodies turn up later, too. Peggy’s cousins Ben and Paul exhibit shifty behavior, and Henry’s preoccupation with Lydia’s youthful purity is worrisome. Themes of class prejudice and police misconduct make themselves known, along with the unbreakable bond of sisterhood. Although unspoken, there’s also some mystery about Peggy’s past romantic history that I couldn’t help wondering about.

The impressive world-building begins on page one, easily conveying the world of Coney Island’s Dreamland park, with its hubbub of activity, brilliantly lit attractions, and popcorn-scented air. This is no sepia-tinted distant past but a sensation-filled present I felt I could step right into. Peggy is a sassy delight who grows in knowledge and confidence, and her transformation from sheltered socialite to take-charge amateur detective is smoothly done. I’d love to meet Peggy again, later on in life, to see the changes she wrought in the world.

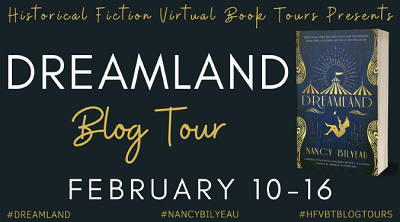

Dreamland was published by Endeavour Quill on January 16th in paperback and ebook. Thanks to the publisher for approving my NetGalley access for the tour with Historical Fiction Virtual Book Tours.

Giveaway!

During the Blog Tour, we are giving away a paperback copy of Dreamland! To enter, please use the Gleam form below.

Giveaway Rules

– Giveaway ends at 11:59 pm EST on February 16th. You must be 18 or older to enter.

– Paperback giveaway is open to US only.

– Only one entry per household.

– All giveaway entrants agree to be honest and not cheat the systems; any suspicion of fraud will be decided upon by blog/site owner and the sponsor, and entrants may be disqualified at our discretion.

– The winner has 48 hours to claim prize or a new winner is chosen.

Dreamland

Published on February 10, 2020 05:00

February 6, 2020

Daniel Kehlmann's Tyll, a darkly humorous picaresque of the Thirty Years' War

A bestseller in Germany, Kehlmann’s newest novel convincingly sweeps Tyll Ulenspiegel, the classic itinerant trickster from German folklore, ahead from medieval times to the seventeenth century and the Thirty Years’ War.

A bestseller in Germany, Kehlmann’s newest novel convincingly sweeps Tyll Ulenspiegel, the classic itinerant trickster from German folklore, ahead from medieval times to the seventeenth century and the Thirty Years’ War.Injecting gleeful dark humor into a setting that manages to feel both fantastically dystopian and historically grounded, the irresistible story highlights the chaotic devastation of the era, during which millions across Europe died, and shows how a prankster like Tyll hardly has a monopoly on foolish behavior.

Some of the book’s eight non-chronological, interlinked episodes are told, in part, from Tyll’s perspective, while in others he appears as a minor character. He survives a rough childhood (and emerges changed after being forced to stay alone in the forest overnight), sees his miller father betrayed by witch-hunting Jesuits, trains as a performer, becomes court jester to the deposed Winter King and Queen of Bohemia, and more.

Kehlmann pokes fun at Germany’s language and traditions as Tyll entertains and insults people across the social spectrum, from royalty to laborers. Indeed, Tyll’s unique position lets him interact with a variety of folk, enhancing the scope of this picaresque tale.

English-speaking readers may not recognize all the historical characters, but no prior knowledge is needed to enjoy Tyll’s adventures.

Daniel Kehlmann's Tyll, his second historical novel (the first was Measuring the World, 2006) will be published by Pantheon next week in the US. The translator is Ross Benjamin. I wrote this starred review for the Jan. 2020 issue of Booklist.

The Thirty Years' War (1618-48) doesn't figure in much English-language fiction. For other examples of novels with this setting, see Laura Libricz' guest post, Writing Novels about the Thirty Years' War, and my review of Heather Richardson's quietly devastating Magdeburg.

Read also Daniel Kehlmann's recent interview with the New York Times.

Published on February 06, 2020 17:43

February 3, 2020

A Long Petal of the Sea, Isabel Allende's epic of the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath

Allende’s fluidly written saga conveys her deep familiarity with the events she depicts, and her intent to illustrate their human impact in a moving way. The scope spans most of the lives of Victor Dalmau, a Republican army medic in 1936 Spain, and Roser Bruguera, a music student taken in by Victor’s family and, later, his brother Guillem’s lover and the mother of Guillem’s child.

Allende’s fluidly written saga conveys her deep familiarity with the events she depicts, and her intent to illustrate their human impact in a moving way. The scope spans most of the lives of Victor Dalmau, a Republican army medic in 1936 Spain, and Roser Bruguera, a music student taken in by Victor’s family and, later, his brother Guillem’s lover and the mother of Guillem’s child.The story follows them over nearly sixty years, beginning with the tumult of the Spanish Civil War. Guillem is killed fighting against the Fascists, news that Victor can’t bear to tell Roser initially. After surviving separate and terrible circumstances that leave them refugees in France, where authorities treat them with contempt and worse, the two marry for practical reasons in order to join Pablo Neruda’s mission transporting over 2000 Spanish exiles to Chile aboard the S.S. Winnipeg. In Santiago, the Dalmaus find many Chileans sympathetic to the Spaniards, while others make them unwelcome.

With a poetic title coming from a poem of Neruda’s referring to Chile as “a long petal of sea and wine and snow,” the novel prompts readers to reflect on the timely themes of cultural adaptation and political refugees’ shared experiences across eras and continents. It also illustrates Victor and Roser’s unusual marriage, which begins out of duty, ripens into affection and mutual admiration, and transforms into something more.

Allende frequently steps away from her characters to relay the larger historical picture, as in this memorable passage: “The exodus from Barcelona was a Dantesque spectacle of thousands of people shivering with cold in a stampede that soon slowed to a straggling procession traveling at the speed of the amputees, the wounded, the old folks and the children.” Incidents from the Dalmaus’ lives are sometimes recited rather than shown, which can be distancing, but Allende’s storytelling abilities are undeniable.

A Long Petal of the Sea was published last week by Ballantine (this review first appeared in February's Historical Novels Review). It was translated from Spanish by Nick Caistor and Amanda Hopkinson.

For two other takes, contrasting ones, on Allende's novel (her 17th), see the reviews in the New York Times, by Paula McLain, and in the Washington Post, by Kristen Millares Young.

Published on February 03, 2020 07:02

January 31, 2020

Historical fiction award winners from ALA Midwinter 2020

The American Library Association Midwinter conference took place last weekend in Philly. I'm a bit late in reporting on the book awards there, so without further ado: here are the historical novels that garnered honors at the conference.

The American Library Association Midwinter conference took place last weekend in Philly. I'm a bit late in reporting on the book awards there, so without further ado: here are the historical novels that garnered honors at the conference.On the Reading List for 2020, which selects the best in genre fiction for adult readers:

In the Historical Fiction category, the winner was Lara Prescott's The Secrets We Kept (Knopf), focusing on two women on a secret mission to smuggle Pasternak's manuscript of Dr. Zhivago out of the USSR so it can be published and finally reach readers worldwide.

On the shortlist for Historical Fiction are: City of Flickering Light by Juliette Fay (1920s Hollywood), The Confessions of Frannie Langton by Sara Collins (Georgian London), The Song of the Jade Lily by Kirsty Manning (WWII-era Shanghai), and Where the Light Enters by Sara Donati (late 19th-century NYC).

Also for the Reading List awards, the winner in Fantasy was Gods of Jade and Shadow by Silvia Moreno-Garcia, set in Mexico during the Jazz Age. The Mystery winner was Alison Sinclair's The Right Sort of Man (see my review), taking place in post-WWII London.

Also for the Reading List awards, the winner in Fantasy was Gods of Jade and Shadow by Silvia Moreno-Garcia, set in Mexico during the Jazz Age. The Mystery winner was Alison Sinclair's The Right Sort of Man (see my review), taking place in post-WWII London.On to the ALA Notable Books for 2020, which (in the Fiction category) are principally novels of a literary bent. Those receiving accolades include:

Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Water Dancer (slavery in 19th-c America)

Michael Crummey, The Innocents (19th-century Newfoundland)

Colson Whitehead, The Nickel Boys (Jim Crow-era Florida)

Among the winners of the Alex Awards, adult books suitable for young adults, was Dominicana by Angie Cruz, an immigrant story set in 1960s New York. The Nickel Boys appears on the winners' list here, too.

Published on January 31, 2020 10:00

January 26, 2020

Review of Cesare: A Novel of War-Torn Berlin by Jerome Charyn

The 1920 German silent horror film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari featured a mad scientist and a somnambulist named Cesare who did his bidding. Adding to his repertoire of unique historical interpretations, Charyn transplants this scenario into Nazi Germany, a setting with nightmarish qualities made real.

The 1920 German silent horror film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari featured a mad scientist and a somnambulist named Cesare who did his bidding. Adding to his repertoire of unique historical interpretations, Charyn transplants this scenario into Nazi Germany, a setting with nightmarish qualities made real.His “Cesare” is Erik Holdermann, who survives childhood trauma to become the henchman of Wilhelm Canaris, head of Germany’s military spy network, after saving the older man’s life. Acting against the Nazi regime from within, they quietly try to help individual Jews escape, but in a place rife with revenge murders and double and triple agents, discovery is inevitable; the only question is when.

The taut story line is full of surreal visuals and elaborate illusions, from Berlin’s Weisse Maus cabaret, reborn as a Gestapo club, to the purported Jewish cultural center at Theresienstadt. The toxic atmosphere distorts everyone’s nature, and if that’s not disturbing enough, there are too many superficially depicted, sex-obsessed female characters who enjoy physical abuse. Inventive, intense, and repellent in equal measure.

Cesare was published this month by Bellevue Literary Press, and I wrote this review for Booklist's Nov 15th issue.

Charyn writes in many styles and has specialized in creative mixtures of fact and fiction focusing on historical characters, such as Teddy Roosevelt (The Perilous Adventures of the Cowboy King) and writers Jerzy Kosinski (Jerzy) and Emily Dickinson (The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson). This was one of those novels I admired more than I enjoyed. It received starred reviews in Kirkus and Publishers Weekly, and is getting raves elsewhere, but I haven't seen other reviews that mention its depiction of women. I appreciated the creative thought behind the presentation of the setting, and the blurb described it as a love story, in part, but I can't say I read it that way.

Published on January 26, 2020 13:40

January 21, 2020

Remembrance by Rita Woods, a unique debut saga of American history

In Rita Woods’ imaginative debut novel, the title refers to an important state of being and a special place.

In Rita Woods’ imaginative debut novel, the title refers to an important state of being and a special place. Remembrance is historical fiction more in the vein of Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad than a traditional narrative, although little from the blurb gives this away. It has a firm thread of fantasy within, or what you might call magical realism. Several of its central female characters – there are four – have abilities, perhaps related to the ancestral practice of Haitian vodun, they can use to protect themselves and others from harm, if they’re able to control them (not always possible). The secret haven called Remembrance, created by one strong-willed woman for this purpose, sits within the borders of antebellum Ohio and shelters a group of the formerly enslaved; white people aren’t permitted to enter.

These four women, past and present, all face varying degrees of racism and its devastating effects and must rely on themselves and one another. Gaelle, an aide in a modern-day Cleveland nursing home, still deals with the tragic aftermath of the Haitian earthquake while devotedly caring for an elderly resident who has the odd ability of dispersing heat, which she also shares. In 1857, in defiance of the freedom she was promised on her 18th birthday, a house slave named Margot and her younger sister are sold away from the Hannigans’ Louisiana plantation after the family’s fortunes fall into ruin. And back in 1791, an African-born enslaved woman called Abigail – not her birth name – is forced to leave Saint Domingue with her mistress, leaving her sons behind, as maroons (escaped slaves) on the island join forces in violent rebellion.

The themes of unpredictable futures, empty promises, and family separations emerge in all three eras. Most beguiling here are the elements of Creole culture woven into the women’s experiences, the original mélange of time periods, and Woods’ ability to describe sights, sounds, and feelings so evocatively. For example, a scene with Abigail encountering brutal cold for the first time in ice-encrusted New Orleans: She blew out a breath and watched it fog in the frigid air, both intrigued and horrified, as it hovered a moment in front of her lips, like some restless winter spirit.

As if often the case in multi-period fiction, the historical settings and personages hold the greatest interest. Gaelle’s story, set so much later than the other two, is less fully developed and seems tangential to the plot at times, while Abigail’s account, which sees her from young womanhood through old age, is an affecting tale that also presents the mysterious legacy she leaves behind. There are also some subtle mistakes in French usage.

Don’t expect to have all your questions answered about how the supernatural world-building works, but for anyone interested in a unique presentation of American history and heritage, the novel is impressively detailed and worthy of note.

Remembrance is published today by Forge; thanks to the publisher for sending me an ARC.

Published on January 21, 2020 04:00

January 16, 2020

Orphans are everywhere in today's historical fiction

From Oliver Twist to Anne Shirley, and from Jane Eyre to Cosette from Les Misérables, orphans play starring roles in many classic works of literature. The hooks for these stories practically write themselves: what circumstances left these young people alone in the world, and how do they learn to survive? Their coming-of-age and ongoing character growth can result in gripping fiction.

And so it may not be surprising to see orphans trending in historical novels. Helping to spur this focus is the huge success of Christina Baker Kline's Orphan Train (2013), a multi-period novel about the homeless and abandoned children from America's eastern cities who were sent out West on trains, in hopes they'd find a better life with foster parents there (the reality, though, was sometimes grim).

Here are a dozen recent historical novels with a distinctive title commonality. Many, though not all, take place during the early decades of the 20th century. How many have you read?

Here are a few more — all very popular with historical fiction readers and book clubs — that incorporate similar themes: children who endure traumatic circumstances during historical times.

For a full list of authors, titles, and settings in the collages above, here's a historical orphan reading list. Please add additional suggestions in the comments.

Elizabeth Brooks, The Orphan of Salt Winds (Tin House, 2019). 1939 England.

Shirley Dickson, The Orphan Sisters (Bookouture, 2019). WWII-era England.

Joanna Goodman, The Home for Unwanted Girls (Harper, 2019). 1950s Quebec.

Stacey Halls, The Lost Orphan (MIRA, April 2020). 1750s London.

Pam Jenoff, The Orphan's Tale (MIRA, 2017). WWII-era Europe.

Jeanne Kalogridis, The Orphan of Florence (St. Martin's Griffin, 2017). 15th-century Florence, Italy.

Lauren Kate, The Orphan's Song (Putnam, 2019). 18th-century Venice.

Natasha Lester, The Paris Orphan (Forever, 2019). WWII-era Paris.

Gemma Liviero, Pastel Orphans (Lake Union, 2015). 1930s Berlin.

Kristina McMorris, Sold on a Monday (Sourcebooks, 2018). Depression-era Pennsylvania.

Glynis Peters, The Secret Orphan (One More Chapter, 2019). WWII-era England.

Sandy Taylor, The Little Orphan Girl (Bookouture, 2018). 1901 Ireland.

Kim van Alkemade, Orphan #8 (William Morrow, 2015). 1920s Manhattan; multi-period.

Ellen Marie Wiseman, The Orphan Collector (Kensington, July 2020). WWI-era Philadelphia.

Lisa Wingate, Before We Were Yours (Ballantine, 2019). 1930s-40s Tennessee; multi-period.

And so it may not be surprising to see orphans trending in historical novels. Helping to spur this focus is the huge success of Christina Baker Kline's Orphan Train (2013), a multi-period novel about the homeless and abandoned children from America's eastern cities who were sent out West on trains, in hopes they'd find a better life with foster parents there (the reality, though, was sometimes grim).

Here are a dozen recent historical novels with a distinctive title commonality. Many, though not all, take place during the early decades of the 20th century. How many have you read?

Here are a few more — all very popular with historical fiction readers and book clubs — that incorporate similar themes: children who endure traumatic circumstances during historical times.

For a full list of authors, titles, and settings in the collages above, here's a historical orphan reading list. Please add additional suggestions in the comments.

Elizabeth Brooks, The Orphan of Salt Winds (Tin House, 2019). 1939 England.

Shirley Dickson, The Orphan Sisters (Bookouture, 2019). WWII-era England.

Joanna Goodman, The Home for Unwanted Girls (Harper, 2019). 1950s Quebec.

Stacey Halls, The Lost Orphan (MIRA, April 2020). 1750s London.

Pam Jenoff, The Orphan's Tale (MIRA, 2017). WWII-era Europe.

Jeanne Kalogridis, The Orphan of Florence (St. Martin's Griffin, 2017). 15th-century Florence, Italy.

Lauren Kate, The Orphan's Song (Putnam, 2019). 18th-century Venice.

Natasha Lester, The Paris Orphan (Forever, 2019). WWII-era Paris.

Gemma Liviero, Pastel Orphans (Lake Union, 2015). 1930s Berlin.

Kristina McMorris, Sold on a Monday (Sourcebooks, 2018). Depression-era Pennsylvania.

Glynis Peters, The Secret Orphan (One More Chapter, 2019). WWII-era England.

Sandy Taylor, The Little Orphan Girl (Bookouture, 2018). 1901 Ireland.

Kim van Alkemade, Orphan #8 (William Morrow, 2015). 1920s Manhattan; multi-period.

Ellen Marie Wiseman, The Orphan Collector (Kensington, July 2020). WWI-era Philadelphia.

Lisa Wingate, Before We Were Yours (Ballantine, 2019). 1930s-40s Tennessee; multi-period.

Published on January 16, 2020 05:22

January 12, 2020

The Daughters of Ironbridge by Mollie Walton, a saga of friendship and class differences in 1830s Shropshire

This is the debut saga from Walton, a successful transition for the author, who also pens historical fiction under her real name, Rebecca Mascull. She writes with admiration for the ordinary people whose toil fueled industrial growth in mid-19th-century England.

This is the debut saga from Walton, a successful transition for the author, who also pens historical fiction under her real name, Rebecca Mascull. She writes with admiration for the ordinary people whose toil fueled industrial growth in mid-19th-century England.The setting is Shropshire in the 1830s, over 50 years since the world’s first iron bridge—which gave the nearby town its name—was constructed over the River Severn. The two protagonists, Anny Woodvine and Margaret King, are unlikely friends. Anny is the amiable, well-loved daughter of a furnace filler at the ironworks, while Margaret, whose ironmaster father despairs of her shyness, lives in privilege at Southover, the wealthy estate overlooking the town.

When the girls first meet by accident in the woodland, Anny, whose mother taught her to read and write, has just taken a job running errands for Mr. King’s estate manager. She is nervous about speaking with the daughter of the house, but Margaret, a lonely girl abused by her older brother, Cyril, tries to put her at ease. They get to know one another through meetings and secret letters, but problems arise years later due to Cyril’s actions, and when a handsome artist comes to town.

Their story is rooted in the history of Ironbridge and the local region, with many examples of the class divide. Anny’s parents take pride in a good day’s work, while Mr. King (somewhat stereotypically) is cold and stern, aiming for profit above all. There’s also some mystery about a baby whose young mother died while carrying her across the iron bridge late one evening, but the plot doesn’t take the obvious route here. Despite some head-hopping which gives away people’s motives too early, The Daughters of Ironbridge is an engaging read with surprising twists, and the ending sets events up nicely for the next in the series.

The novel was published by Zaffre in 2019; this was a personal purchase I'd reviewed for the Historical Novels Review. The next book, The Secrets of Ironbridge , will be published in April 2020. Some history: the town of Ironbridge is described and promoted as the "birthplace of the Industrial Revolution."

View of the Iron Bridge, 2015, with its previous grey color.

View of the Iron Bridge, 2015, with its previous grey color.Photo by Simon Hark, via Wikimedia Commons - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Published on January 12, 2020 05:44

January 6, 2020

Written in Their Stars by Elizabeth St. John, her newest English Civil War family saga

Spanning fifteen years, from the height of the English Civil War to after the Restoration, Elizabeth St. John’s third volume of her Lydiard Chronicles is the most complex yet. It continues to add new shadings of personality to her ongoing cast of characters while homing in on three women from her family tree whose actions strongly influenced their times, and vice versa.

Spanning fifteen years, from the height of the English Civil War to after the Restoration, Elizabeth St. John’s third volume of her Lydiard Chronicles is the most complex yet. It continues to add new shadings of personality to her ongoing cast of characters while homing in on three women from her family tree whose actions strongly influenced their times, and vice versa. Luce Hutchinson, daughter of Lucy (St. John) Apsley, heroine of the first book, The Lady of the Tower , sits firmly on the side of Parliament and yearns for a world without oppressive monarchical rule. As one of the signers of the warrant for Charles I’s execution, Luce's husband Colonel John Hutchinson, a well-known Puritan leader, makes a mark on history that can’t be undone.

With that action, John further alienates Luce’s brother, Allen, a fervent Cavalier who chooses to go into exile in France rather than remain in Cromwell’s England. With him goes his wife, Frances, and young daughter, Isabella; they risk being called traitors for joining the court of Charles I’s queen in Paris, but Allen has his eye on the long game, planning to bide his time and working toward the restoration of Prince Charles. Their cousin Nan Wilmot, the intelligent and crafty Countess of Rochester, does what she must to survive the tumultuous era, playing both sides to ensure her sons’ inheritance is kept intact. Nan sits at the heart of a spy network and enlists Frances in her secret mission to re-establish the monarchy.

For readers most familiar with the English Civil War though its accounts of battles and prominent men, this evocative saga will shift your impressions. St. John has based her novel on family memoirs, and their stories are worth knowing. She also weaves in other little-known facets of history, such as the unsung role of Susan Hyde (sister of the Earl of Clarendon, the future James II’s father-in-law). Barbara Villiers looms large in history as Charles II’s favorite mistress, but in Written in Their Stars, readers also see her as the lissome St. John cousin who comes to play a surprising part not just in the royal court but in her family’s future.

Despite the political leanings that divide them, the characters remain emotionally close to each other as family—a delicate balance evoked well in the writing. The relationships between three sets of spouses are also a highlight. While this novel can stand alone, I recommend reading the previous two books first to fill in all of the background to the characters, and what led them to the paths they chose.

Written in Their Stars was published by Falcon Historical in November (ebook and paperback, 384pp).

Giveaway

During the Blog Tour, we are giving away two signed copies of Written in their Stars! To enter, please use the Gleam form below.

Giveaway Rules

– Giveaway ends at 11:59 pm EST on January 10th. You must be 18 or older to enter.

– Paperback giveaway is open to US residents only.

– Only one entry per household.

– All giveaway entrants agree to be honest and not cheat the systems; any suspicion of fraud will be decided upon by blog/site owner and the sponsor, and entrants may be disqualified at our discretion.

– The winner has 48 hours to claim prize or a new winner is chosen.

Written in Their Stars

Published on January 06, 2020 05:00