Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 107

March 12, 2014

Local Customs by Audrey Thomas, a writer's journey into 19th-century Africa

In Local Customs, Canadian novelist Audrey Thomas examines the out-of-the-ordinary life and even more curious death of an early 19th-century woman writer, Letitia Elizabeth Landon (1802-1838), who wrote poetry and novels under the initials "L.E.L."

In Local Customs, Canadian novelist Audrey Thomas examines the out-of-the-ordinary life and even more curious death of an early 19th-century woman writer, Letitia Elizabeth Landon (1802-1838), who wrote poetry and novels under the initials "L.E.L."The story uses a multi-voiced structure that's both quirky and effective. The main narrator is Letitia (Letty), who reveals up front that she's speaking from beyond the grave. This can be unnerving at first, but this technique gives readers a fuller picture of events than they would have otherwise.

In June of 1838, Letty marries Scottish-born George Maclean, the British governor of the Gold Coast (now Ghana), and moves with him to Africa. However, within two months of her arrival, she is found dead, a bottle of prussic acid clutched in her hand. Although most white settlers in the region don't last long – tropical fevers have killed off so many missionaries and their wives that their graveyards flourish more than their religion – Letty had thrived in the climate. What really happened to her?

In a witty and rather lofty tone, Letty details the events that led up to her demise: her genteel family background, her unlikely courtship and marriage to George, the mismatched couple's growing affection for one another, the truth about her scandalous past, her lonely life at Cape Coast Castle, her growing friendship with a visiting Scotsman, and her growing fear that she's being watched and threatened in her own home.

A dedicated professional writer, Letty is pointedly observant, self-confident... and also rather high-maintenance. Although she's an entertaining conversationalist at social gatherings, she gives the impression of being difficult to live with. Amid a sea of frilly debutantes obsessed with their London Seasons, Letty is a Victorian original.

"It is curious how much of its romantic character a country owes to strangers, perhaps because they know least about it," she wisely states in the beginning. She loves the idea of an African adventure, and Thomas elaborates on many of the local customs that fascinate and sometimes disgust Letty – like Englishmen's habits of taking native mistresses, or "country wives."

Interspersed with Letty's words, a handful of other characters chime in with their perspectives on her life and sudden death, almost as if this were a play. Local Customs is the type of intelligent literary mystery that doesn't present a definitive answer but gives readers sufficient information to draw their own conclusions. Best of all is the spotlight it shines on Letitia Landon, a talented writer who has been undeservedly forgotten.

Local Customs was published in February 2014 by Canada's Dundurn Press ($16.99 pb in US & Canada / $4.99 ebook). Thanks to the publisher for granting me access via NetGalley.

Published on March 12, 2014 06:00

March 10, 2014

The Dreaming: Walks Through Mist, a guest essay by Kim Murphy

Today I'm pleased to welcome my friend Kim Murphy, who has an essay about a fascinating but little-known aspect of early American history which forms the background to her latest fiction release, The Dreaming: Walks Through Mist. I was absorbed by the novel when I read it several years ago; the research is sound, and I can highly recommend it to readers of time-slips (one of my favorites) and anyone interested in colonial America or Native American cultures.

~

The Dreaming: Walks Through Mistby Kim Murphy

Witch trials in Virginia?

Except for some people who live in the tidewater region of the state, few realize that Virginia was the first to hold witch trials on the North American continent. Not only are the Virginia trials overshadowed by Salem, but the records that have survived to modern times are sparse. Thanks to the Civil War, many of the 17th century records were burned during the 19th century (another area of history that I know very well!).

Unlike in Salem, only one woman was known to have been executed. But how many records were lost? No one will ever know. The journey of writing my story led me to read more about England, where the colonists originated from. I discovered Emma Wilby's wonderful book Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic Visionary Traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic. With an anthropology degree, I have always been intrigued by shamans, and I was off and running.

Unlike in Salem, only one woman was known to have been executed. But how many records were lost? No one will ever know. The journey of writing my story led me to read more about England, where the colonists originated from. I discovered Emma Wilby's wonderful book Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic Visionary Traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic. With an anthropology degree, I have always been intrigued by shamans, and I was off and running.

Even though historians disagree whether the cunning folk (English shamans) ever reached the American shores, I uncovered two Virginia witch trials that sounded very much like cunning women. Yet, something was missing.

When the colonists first arrived on Virginia's shores, the land was already inhabited. Besides the John Smith/Pocahontas myth, I knew nothing about the Algonquian-speaking people, commonly referred to as the Powhatan. In my pursuit to learn more, not only did I read books, but I visited the historic sites. Jamestown is the original site where the colonists made the first permanent English settlement in North America, and Jamestown Settlement is a living history park where the 17th century comes alive. The Citie of Henricus is also a living history park portraying the second English settlement. Like Jamestown Settlement, it includes exhibits and demonstrations of how the Indians of the time lived, but unlike Jamestown, Henricus did not survive Opechancanough's organized attacks in 1622.

Also on my stops, I included visits to the Pamunkey and Mattaponi museums.The paramount chief Powhatan was a member of the Pamunkey tribe, and his daughter, Pocahontas, was Mattaponi (the Algonquian-speaking tribes of Virginia traced their lineage through the women). These two tribes were part of the Powhatan chiefdom and still live on reservations in Virginia to this day. I also spoke with modern descendants and was drawn into a world that I could have never imagined.

Also on my stops, I included visits to the Pamunkey and Mattaponi museums.The paramount chief Powhatan was a member of the Pamunkey tribe, and his daughter, Pocahontas, was Mattaponi (the Algonquian-speaking tribes of Virginia traced their lineage through the women). These two tribes were part of the Powhatan chiefdom and still live on reservations in Virginia to this day. I also spoke with modern descendants and was drawn into a world that I could have never imagined.

In my story, The Dreaming: Walks Through Mist I have blended modern times with romance, fantasy, paranormal, and the 17th century.

I will be continuing the story with The Dreaming: Wind Talker, which will hopefully be a fall release. My most recent release, however, is my first nonfiction title, I Had Rather Die: Rape in the Civil War, the first book dedicated to the topic.

Thank you for letting me stop by. For further information, please visit my website www.KimMurphy.Net.

~

Kim Murphy's The Dreaming: Walks Through Mist was published by Coachlight Press in 2011 ($15.95 trade pb / $3.99 ebook). I Had Rather Die: Rape in the Civil War, also from Coachlight Press, was published in January 2014 ($14.95 trade pb / $21.95 hardcover).

~

The Dreaming: Walks Through Mistby Kim Murphy

Witch trials in Virginia?

Except for some people who live in the tidewater region of the state, few realize that Virginia was the first to hold witch trials on the North American continent. Not only are the Virginia trials overshadowed by Salem, but the records that have survived to modern times are sparse. Thanks to the Civil War, many of the 17th century records were burned during the 19th century (another area of history that I know very well!).

Unlike in Salem, only one woman was known to have been executed. But how many records were lost? No one will ever know. The journey of writing my story led me to read more about England, where the colonists originated from. I discovered Emma Wilby's wonderful book Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic Visionary Traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic. With an anthropology degree, I have always been intrigued by shamans, and I was off and running.

Unlike in Salem, only one woman was known to have been executed. But how many records were lost? No one will ever know. The journey of writing my story led me to read more about England, where the colonists originated from. I discovered Emma Wilby's wonderful book Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic Visionary Traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic. With an anthropology degree, I have always been intrigued by shamans, and I was off and running.Even though historians disagree whether the cunning folk (English shamans) ever reached the American shores, I uncovered two Virginia witch trials that sounded very much like cunning women. Yet, something was missing.

When the colonists first arrived on Virginia's shores, the land was already inhabited. Besides the John Smith/Pocahontas myth, I knew nothing about the Algonquian-speaking people, commonly referred to as the Powhatan. In my pursuit to learn more, not only did I read books, but I visited the historic sites. Jamestown is the original site where the colonists made the first permanent English settlement in North America, and Jamestown Settlement is a living history park where the 17th century comes alive. The Citie of Henricus is also a living history park portraying the second English settlement. Like Jamestown Settlement, it includes exhibits and demonstrations of how the Indians of the time lived, but unlike Jamestown, Henricus did not survive Opechancanough's organized attacks in 1622.

Also on my stops, I included visits to the Pamunkey and Mattaponi museums.The paramount chief Powhatan was a member of the Pamunkey tribe, and his daughter, Pocahontas, was Mattaponi (the Algonquian-speaking tribes of Virginia traced their lineage through the women). These two tribes were part of the Powhatan chiefdom and still live on reservations in Virginia to this day. I also spoke with modern descendants and was drawn into a world that I could have never imagined.

Also on my stops, I included visits to the Pamunkey and Mattaponi museums.The paramount chief Powhatan was a member of the Pamunkey tribe, and his daughter, Pocahontas, was Mattaponi (the Algonquian-speaking tribes of Virginia traced their lineage through the women). These two tribes were part of the Powhatan chiefdom and still live on reservations in Virginia to this day. I also spoke with modern descendants and was drawn into a world that I could have never imagined.In my story, The Dreaming: Walks Through Mist I have blended modern times with romance, fantasy, paranormal, and the 17th century.

I will be continuing the story with The Dreaming: Wind Talker, which will hopefully be a fall release. My most recent release, however, is my first nonfiction title, I Had Rather Die: Rape in the Civil War, the first book dedicated to the topic.

Thank you for letting me stop by. For further information, please visit my website www.KimMurphy.Net.

~

Kim Murphy's The Dreaming: Walks Through Mist was published by Coachlight Press in 2011 ($15.95 trade pb / $3.99 ebook). I Had Rather Die: Rape in the Civil War, also from Coachlight Press, was published in January 2014 ($14.95 trade pb / $21.95 hardcover).

Published on March 10, 2014 05:30

March 8, 2014

Voices From the Past: What I have learned from reissuing a historical novel, a guest essay by Ian Skillicorn

I'm happy to present a guest essay for Small Press Month that offers a small press publisher's perspective. Corazon Books specializes in women's and historical fiction, and here publisher Ian Skillicorn speaks about his experience reissuing a favorite historical novel.

~

Voices From the Past: What I Have Learned from Reissuing a Historical Novel Ian Skillicorn, Corazon Books

When I was given a copy of Lily’s Daughter, written by Diana Raymond, the novel had been out of print for some time. While extremely popular when it was first published in the 1980s, it had been neglected in more recent years. Almost as soon as I began to read it, I knew that I wanted to bring this work back to the attention of the reading public.

My fiction imprint, Corazon Books, specialises in digital editions of out-of-print works (although it is now expanding to include original fiction and print editions of some titles). For a while, I had been actively looking to publish some historical fiction, having already secured the license for an ebook edition of a Catherine Gaskin novel with a strong historical element.

Lily’s Daughter is the coming-of-age story of seventeen-year-old Jessica Mayne, in 1930s England. At its heart, it is a study on love and loss. After committing her mother to a psychiatric hospital, Jessica is summoned to the home of her estranged Aunt Imogen. There she meets a number of people who will have a profound influence on her. Jessica is drawn to her charming but fickle cousin Guy, while Aaron, a Polish Jew about to return to Warsaw, warns her of the inevitable conflict about to sweep across Europe and beyond. Despite dealing with serious issues, Lily’s Daughter is a touching tale told with much warmth and wit.

Lily’s Daughter is the coming-of-age story of seventeen-year-old Jessica Mayne, in 1930s England. At its heart, it is a study on love and loss. After committing her mother to a psychiatric hospital, Jessica is summoned to the home of her estranged Aunt Imogen. There she meets a number of people who will have a profound influence on her. Jessica is drawn to her charming but fickle cousin Guy, while Aaron, a Polish Jew about to return to Warsaw, warns her of the inevitable conflict about to sweep across Europe and beyond. Despite dealing with serious issues, Lily’s Daughter is a touching tale told with much warmth and wit.

I was introduced to Lily’s Daughter by my mother, who knows the author’s family. She had been lent a copy by Diana Raymond’s daughter-in-law, and felt that I would also appreciate it. At that point, I didn’t know a great deal about Diana Raymond, who died in 2009. I was more familiar with the name of her husband, the author Ernest Raymond. His books had lined my grandparents’ bookshelves, and were now on mine, as I had inherited them.

What I did know, from reading Lily’s Daughter, was that Diana Raymond was a perceptive writer with an acute understanding of the human character. In fact, The Daily Telegraph called her ‘… an observant, sensitive writer whose characters come alive’, while Country Life said that ‘The outstanding characteristic of Diana Raymond’s work as a novelist is the sagacity with which she feels her way into the personality of her people.’ Having gained the rights to publish a new edition of the novel, I wanted to learn more about Diana Raymond. Not only would this give me a deeper insight into her writing, it would enable me to acquaint a new generation of readers with the author. This led me to research both the author’s life, and the times she lived through.

Diana Raymond was born in 1916, the year before her father died in the preliminary bombardment to The Third Battle of Ypres. The loss of her father in the fighting is one of the experiences she shared with her protagonist in Lily’s Daughter. By coincidence, I came to publish the book in time for the centenary of the start of the Great War. It prompted me to find out more about the fatherless children of the First World War. I read newspapers from the era, and was struck by the many appeals from charities and orphanages for financial aid to help the children of the fallen. Diana herself benefited from this charity, by being educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College thanks to the Officers’ Families Fund.

Diana Raymond was born in 1916, the year before her father died in the preliminary bombardment to The Third Battle of Ypres. The loss of her father in the fighting is one of the experiences she shared with her protagonist in Lily’s Daughter. By coincidence, I came to publish the book in time for the centenary of the start of the Great War. It prompted me to find out more about the fatherless children of the First World War. I read newspapers from the era, and was struck by the many appeals from charities and orphanages for financial aid to help the children of the fallen. Diana herself benefited from this charity, by being educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College thanks to the Officers’ Families Fund.

My research into Diana’s life was made much easier by having personal contact with members of her family. I was very fortunate to be given a copy of her unpublished memoir, Are We Nearly There? Reading it in one sitting, it left me with a strong sense of this intelligent and enlightened woman. I wish I had had the opportunity to meet her. I understood how Diana’s love of poetry, especially that of Keats, helped formed a bond with the father she never knew. A Lecturer in English at Goldsmiths College, London University, his last book, published posthumously, was an anthology of Keats. I was moved by her account of the first visit, as an adult, to her father’s grave in Belgium.

I was fascinated by Diana’s experiences of the next world war through which she lived. I found out that she worked for the British Government both before and during the Second World War. In fact, at one time she was personal assistant to General Ismay, who went on to be Churchill’s chief military assistant, and then the first Secretary General of NATO. Married during the war, Diana and Ernest would watch air raids on London from their home in Hampstead. These recollections inspired me to read more about the war on Britain’s home front, through contemporary newspaper reports and eyewitness accounts.

Although my interest and research into the life and times of Diana Raymond is far from over, I now feel I have an even greater appreciation of Lily’s Daughter and its author. This literary and historical journey has been an enriching one. I will leave the last word to Diana. Speaking to Contemporary Authors about her work, she said: ‘I would hope that what I write expresses for some people an aspect of their experiences, joys or griefs, that makes them say, “Yes! This is what I felt but I could never get it into words”.’

Sources:

Are We Nearly There? Diana Raymond (private memoir)

Contemporary Authors Online, Gale, 2009.

About Corazon Books

Corazon Books is a successful and expanding publisher of women’s and historical fiction. Its aim is simple - to bring readers great stories with heart. Recent successes include a Top 10 bestseller on Amazon, and a #1 in the Women Writers & Fiction category.

Corazon Books publishes both new fiction and reissues of popular out-of-print works. Its list includes the first digital edition of a novel by the internationally bestselling ‘Queen of Storytellers’ Catherine Gaskin. The imprint also supports and encourages new writers with a number of writing competitions held throughout each year. It is currently running a competition in partnership with the Mature Times newspaper, for an unpublished writer aged over 50 to win a publishing deal.

Full details can be found at www.greatstorieswithheart.com. Diana Raymond's Lily's Daughter is available as an ebook from Corazon Books from Amazon UK (£1.99) and Amazon ($3.99).

About Ian Skillicorn

Ian Skillicorn is a publisher and audio producer. He established his successful fiction imprint in 2012. For many years Ian has produced audio for writers and publishers, including an audio story project supported by Arts Council England. Ian is also the director of National Short Story Week, which he founded in 2010. He is a frequent speaker and workshop leader at writing conferences around the UK.

~

Voices From the Past: What I Have Learned from Reissuing a Historical Novel Ian Skillicorn, Corazon Books

When I was given a copy of Lily’s Daughter, written by Diana Raymond, the novel had been out of print for some time. While extremely popular when it was first published in the 1980s, it had been neglected in more recent years. Almost as soon as I began to read it, I knew that I wanted to bring this work back to the attention of the reading public.

My fiction imprint, Corazon Books, specialises in digital editions of out-of-print works (although it is now expanding to include original fiction and print editions of some titles). For a while, I had been actively looking to publish some historical fiction, having already secured the license for an ebook edition of a Catherine Gaskin novel with a strong historical element.

Lily’s Daughter is the coming-of-age story of seventeen-year-old Jessica Mayne, in 1930s England. At its heart, it is a study on love and loss. After committing her mother to a psychiatric hospital, Jessica is summoned to the home of her estranged Aunt Imogen. There she meets a number of people who will have a profound influence on her. Jessica is drawn to her charming but fickle cousin Guy, while Aaron, a Polish Jew about to return to Warsaw, warns her of the inevitable conflict about to sweep across Europe and beyond. Despite dealing with serious issues, Lily’s Daughter is a touching tale told with much warmth and wit.

Lily’s Daughter is the coming-of-age story of seventeen-year-old Jessica Mayne, in 1930s England. At its heart, it is a study on love and loss. After committing her mother to a psychiatric hospital, Jessica is summoned to the home of her estranged Aunt Imogen. There she meets a number of people who will have a profound influence on her. Jessica is drawn to her charming but fickle cousin Guy, while Aaron, a Polish Jew about to return to Warsaw, warns her of the inevitable conflict about to sweep across Europe and beyond. Despite dealing with serious issues, Lily’s Daughter is a touching tale told with much warmth and wit. I was introduced to Lily’s Daughter by my mother, who knows the author’s family. She had been lent a copy by Diana Raymond’s daughter-in-law, and felt that I would also appreciate it. At that point, I didn’t know a great deal about Diana Raymond, who died in 2009. I was more familiar with the name of her husband, the author Ernest Raymond. His books had lined my grandparents’ bookshelves, and were now on mine, as I had inherited them.

What I did know, from reading Lily’s Daughter, was that Diana Raymond was a perceptive writer with an acute understanding of the human character. In fact, The Daily Telegraph called her ‘… an observant, sensitive writer whose characters come alive’, while Country Life said that ‘The outstanding characteristic of Diana Raymond’s work as a novelist is the sagacity with which she feels her way into the personality of her people.’ Having gained the rights to publish a new edition of the novel, I wanted to learn more about Diana Raymond. Not only would this give me a deeper insight into her writing, it would enable me to acquaint a new generation of readers with the author. This led me to research both the author’s life, and the times she lived through.

Diana Raymond was born in 1916, the year before her father died in the preliminary bombardment to The Third Battle of Ypres. The loss of her father in the fighting is one of the experiences she shared with her protagonist in Lily’s Daughter. By coincidence, I came to publish the book in time for the centenary of the start of the Great War. It prompted me to find out more about the fatherless children of the First World War. I read newspapers from the era, and was struck by the many appeals from charities and orphanages for financial aid to help the children of the fallen. Diana herself benefited from this charity, by being educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College thanks to the Officers’ Families Fund.

Diana Raymond was born in 1916, the year before her father died in the preliminary bombardment to The Third Battle of Ypres. The loss of her father in the fighting is one of the experiences she shared with her protagonist in Lily’s Daughter. By coincidence, I came to publish the book in time for the centenary of the start of the Great War. It prompted me to find out more about the fatherless children of the First World War. I read newspapers from the era, and was struck by the many appeals from charities and orphanages for financial aid to help the children of the fallen. Diana herself benefited from this charity, by being educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College thanks to the Officers’ Families Fund. My research into Diana’s life was made much easier by having personal contact with members of her family. I was very fortunate to be given a copy of her unpublished memoir, Are We Nearly There? Reading it in one sitting, it left me with a strong sense of this intelligent and enlightened woman. I wish I had had the opportunity to meet her. I understood how Diana’s love of poetry, especially that of Keats, helped formed a bond with the father she never knew. A Lecturer in English at Goldsmiths College, London University, his last book, published posthumously, was an anthology of Keats. I was moved by her account of the first visit, as an adult, to her father’s grave in Belgium.

I was fascinated by Diana’s experiences of the next world war through which she lived. I found out that she worked for the British Government both before and during the Second World War. In fact, at one time she was personal assistant to General Ismay, who went on to be Churchill’s chief military assistant, and then the first Secretary General of NATO. Married during the war, Diana and Ernest would watch air raids on London from their home in Hampstead. These recollections inspired me to read more about the war on Britain’s home front, through contemporary newspaper reports and eyewitness accounts.

Although my interest and research into the life and times of Diana Raymond is far from over, I now feel I have an even greater appreciation of Lily’s Daughter and its author. This literary and historical journey has been an enriching one. I will leave the last word to Diana. Speaking to Contemporary Authors about her work, she said: ‘I would hope that what I write expresses for some people an aspect of their experiences, joys or griefs, that makes them say, “Yes! This is what I felt but I could never get it into words”.’

Sources:

Are We Nearly There? Diana Raymond (private memoir)

Contemporary Authors Online, Gale, 2009.

About Corazon Books

Corazon Books is a successful and expanding publisher of women’s and historical fiction. Its aim is simple - to bring readers great stories with heart. Recent successes include a Top 10 bestseller on Amazon, and a #1 in the Women Writers & Fiction category.

Corazon Books publishes both new fiction and reissues of popular out-of-print works. Its list includes the first digital edition of a novel by the internationally bestselling ‘Queen of Storytellers’ Catherine Gaskin. The imprint also supports and encourages new writers with a number of writing competitions held throughout each year. It is currently running a competition in partnership with the Mature Times newspaper, for an unpublished writer aged over 50 to win a publishing deal.

Full details can be found at www.greatstorieswithheart.com. Diana Raymond's Lily's Daughter is available as an ebook from Corazon Books from Amazon UK (£1.99) and Amazon ($3.99).

About Ian Skillicorn

Ian Skillicorn is a publisher and audio producer. He established his successful fiction imprint in 2012. For many years Ian has produced audio for writers and publishers, including an audio story project supported by Arts Council England. Ian is also the director of National Short Story Week, which he founded in 2010. He is a frequent speaker and workshop leader at writing conferences around the UK.

Published on March 08, 2014 07:00

March 6, 2014

Small press spotlight: new and forthcoming historical novels, part 2

And here's a second gallery of upcoming historical novels from small & independent presses. In many cases they incorporate settings used by very few other novelists – and the variety they offer is just one of the reasons these publishers play a valuable role in the publishing industry. If you missed Part 1, you can find it here.

The next gallery, covering historical mysteries, will be posted next Friday, March 14th, when I'll be attending (and hanging out with other librarians and publishers at) the Public Library Association conference in Indianapolis. More guest posts and reviews will be forthcoming before then, too.

This volume about Edwin, High King of Britain in the early 7th century, launches a new series about the Christian kings of Northumbria. Lion Fiction, April 2014.

A fictional retelling of a remarkable man, Thomas Greene Wiggins ("Blind Tom,"), a visually impaired musical performer who was born into slavery in the mid-19th century. Graywolf, June.

From the pseudonymous author of The Ruins of Lace comes a new historical novel about three women – a nun, an outcast, and a princess – in 10th-century France. Each prays desperately to Saint Catherine for a miracle to change her life. Sourcebooks, April 2014.

This romantic historical novel of ancient times retells the story of a legendary pair of lovers: Helen, Princess of Sparta, and Paris of Troy. Mythmakers, April 2014.

A sweeping romantic epic set at the time of Mary Queen of Scots, originally published in 1983 (as Love's Pirate). The author is best known today for her contemporary mysteries. Camel Press, February 2014.

In small-town Wales in the '20s, a shy undertaker impulsively proposes marriage to a young woman he hardly knows but quickly regrets it – only to find he can't withdraw his offer so easily. This novel of social morals and values seems light and quirky at first... but keep reading. (I can highly recommend it.) Europa Editions, February 2014.

A novel with parallel narratives involving mothers and daughters, with the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 at their center. The author is the daughter of Hungarian refugees and incorporates details from her family history in her latest novel. Poisoned Pen Press, September 2013.

Literary fiction about a real-life artist, Wang Meng, in 14th-century China; he encounters many memorable characters as he travels through a politically turbulent land. Overlook, April 2014.

This multi-voiced narrative, set in Northampton, Massachusetts, in the 18th century, follows the life and times of Jonathan Edwards, a powerful theologian who helped bring about the First Great Awakening. Small Beer Press, October 2013.

A novel of war, politics, and family set in a troubled 15th-century Scotland, as John Sempill, the last son in his line after his father's death on the battlefield, must forge a new life under the country's new king. Hadley Rille, September 2013.

A novel comprised of three interlinked stories set in 14th-century France; Christine de Pizan, a notable woman writer of medieval Europe, figures strongly in the first installment. Fireship, May 2013.

Wiederanders' debut takes as its subject the relationship between Fanny Osbourne, an aspiring artist and still-married American, and Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson. Yes, this is the same couple featured in another recent novel, although this one has a narrower focus: the year 1879, when he crossed sea and land to convince her to marry him. Fireship, March 2014.

The next gallery, covering historical mysteries, will be posted next Friday, March 14th, when I'll be attending (and hanging out with other librarians and publishers at) the Public Library Association conference in Indianapolis. More guest posts and reviews will be forthcoming before then, too.

This volume about Edwin, High King of Britain in the early 7th century, launches a new series about the Christian kings of Northumbria. Lion Fiction, April 2014.

A fictional retelling of a remarkable man, Thomas Greene Wiggins ("Blind Tom,"), a visually impaired musical performer who was born into slavery in the mid-19th century. Graywolf, June.

From the pseudonymous author of The Ruins of Lace comes a new historical novel about three women – a nun, an outcast, and a princess – in 10th-century France. Each prays desperately to Saint Catherine for a miracle to change her life. Sourcebooks, April 2014.

This romantic historical novel of ancient times retells the story of a legendary pair of lovers: Helen, Princess of Sparta, and Paris of Troy. Mythmakers, April 2014.

A sweeping romantic epic set at the time of Mary Queen of Scots, originally published in 1983 (as Love's Pirate). The author is best known today for her contemporary mysteries. Camel Press, February 2014.

In small-town Wales in the '20s, a shy undertaker impulsively proposes marriage to a young woman he hardly knows but quickly regrets it – only to find he can't withdraw his offer so easily. This novel of social morals and values seems light and quirky at first... but keep reading. (I can highly recommend it.) Europa Editions, February 2014.

A novel with parallel narratives involving mothers and daughters, with the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 at their center. The author is the daughter of Hungarian refugees and incorporates details from her family history in her latest novel. Poisoned Pen Press, September 2013.

Literary fiction about a real-life artist, Wang Meng, in 14th-century China; he encounters many memorable characters as he travels through a politically turbulent land. Overlook, April 2014.

This multi-voiced narrative, set in Northampton, Massachusetts, in the 18th century, follows the life and times of Jonathan Edwards, a powerful theologian who helped bring about the First Great Awakening. Small Beer Press, October 2013.

A novel of war, politics, and family set in a troubled 15th-century Scotland, as John Sempill, the last son in his line after his father's death on the battlefield, must forge a new life under the country's new king. Hadley Rille, September 2013.

A novel comprised of three interlinked stories set in 14th-century France; Christine de Pizan, a notable woman writer of medieval Europe, figures strongly in the first installment. Fireship, May 2013.

Wiederanders' debut takes as its subject the relationship between Fanny Osbourne, an aspiring artist and still-married American, and Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson. Yes, this is the same couple featured in another recent novel, although this one has a narrower focus: the year 1879, when he crossed sea and land to convince her to marry him. Fireship, March 2014.

Published on March 06, 2014 19:00

March 5, 2014

The Lost Colony Series: How much of it is true? A guest post by Jo Grafford

Today Jo Grafford, author of the romantic historical adventure novels Breaking Ties and Trail of Crosses (Astraea Press), details her in-depth research into the fate of the lost colonists of Roanoke – and explains how modern technology has been providing insight into one of America's greatest unsolved mysteries. And she provides an abundance of links for readers to explore further.

~

The Lost Colony Series: How Much of It Is True?Jo Grafford

Before I became an author, I imagined writing fiction would be easy. I mean, you get to make everything up, right? Wrong! It took more than five years of research to write my debut historical, Breaking Ties, first book in the Lost Colony Series. Let me take you behind the scenes for a few minutes.

For 426 years, historians have debated the fate of the Lost Colonists. One of my all-time favorite books on the topic is Lee Miller’s Roanoke: Solving the Mystery of the Lost Colony. She builds a compelling case for internal sabotage of the City of Raleigh’s risky investment venture, which completely appealed to my background in banking and investing. Her claim started me on the path of asking, “What if?”

What if these brave men and women were not simply slaughtered en masse as so many historians have suggested? What if the truth was much less tidy, far more complex, and completely mind-boggling like reality so often is?

What if these brave men and women were not simply slaughtered en masse as so many historians have suggested? What if the truth was much less tidy, far more complex, and completely mind-boggling like reality so often is?

In my quest for answers, I browsed original ship manifests and supply lists, read various period sailing journals, delved into church registries and library archives, and even took a road trip to visit Roanoke Island. I stood on the same patch of land the first English settlers assembled and imagined the craggy, overgrown terrain – barren of its current beach homes and boat docks – as their only welcome.

Then I started writing Breaking Ties nearly six years ago to try and piece together the “rest of the story” of these Lost Colonists – the never-been-told parts that occurred after all the official recordings of their journey stopped. This project was made easier when a news broke in October 2012 about a new clue concerning their fate.

In a nutshell, experts used laser technology to raise a patch on an original Lost Colony map, held for centuries at the British Museum. They uncovered the sketch of a fort located 50 miles inland where the Roanoke and Chowan Rivers converge. This location is an perfect match to one of the Lost Colonists' final statements to Governor John White (the last Englishman to see them alive) of their intent “to move 50 miles into the main[land].” This is the first clue produced that seems to offers conclusive evidence of survivors.

Fast-forward the clock to this past December. The First Colony Foundation employed radar and sonar technology to explore what lies beneath this patch. Their work is far from complete, but guess what? Already, they’ve discovered more exciting evidence that continues to support the underlying premise of my Lost Colony Series – that there were survivors!

author Jo GraffordThe Lost Colony Series is based on real people and real events. I even use the real names taken from the ship manifest. The novel also follows an accurate historical timeline. So where did I find the details to fill in all the missing pieces? It was a real treasure hunt, I assure you. John White’s journals and other writings only give us a shadowy glimpse of a day in the life of his shipmates aboard their fleet of three ships. I rounded out the depth of the characters, their background, and conversations in Breaking Ties with an enormous amount of digging through period books, paintings, sketches, and websites.

author Jo GraffordThe Lost Colony Series is based on real people and real events. I even use the real names taken from the ship manifest. The novel also follows an accurate historical timeline. So where did I find the details to fill in all the missing pieces? It was a real treasure hunt, I assure you. John White’s journals and other writings only give us a shadowy glimpse of a day in the life of his shipmates aboard their fleet of three ships. I rounded out the depth of the characters, their background, and conversations in Breaking Ties with an enormous amount of digging through period books, paintings, sketches, and websites.

Since the Lyon – the largest of the three ships in my novel – was truly piloted by an ex-pirate, Simon Fernandez, I spent many hours researching famous pirates and pirate ships, pirate talk, and pirate weapons. Not only is it relevant to my story, it’s a darn lot of fun saying “Argh,” “Ahoy there, mate,” and “Shiver me timbers!”

Alas, the famous “Fifteen men on a dead man’s chest...Yo, ho, ho, and a bottle of rum,” is an excerpt from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, published in the 1800s. Since Breaking Ties is set in 1587, I had to dig further back in history for the seaman shanties I ended up using. I discovered the “gallowsbirds all, gallowsbirds all” shanty in a book titled The Mayflower by Kate Caffrey and Googled my way to the complete text online. This was chanted by the sailors like a mournful dirge to mask the cries of a certain young lad in Breaking Ties during his well-deserved but completely heart-wrenching flogging after a few of my colonists were pressed into sailing duty. To listen to some classic sea shanties online, see the Brethren of the Coast website.

To immerse myself fully in the rich flavor of 16th-century maritime life, I browsed the free text of The Elizabethan Sea Dogs by William Wood. I also found Dr. Ian Friel’s lecture about Elizabethan Merchant Ships and Shipbuilding to be helpful. The full webinar is posted on the Gresham College website.

To immerse myself fully in the rich flavor of 16th-century maritime life, I browsed the free text of The Elizabethan Sea Dogs by William Wood. I also found Dr. Ian Friel’s lecture about Elizabethan Merchant Ships and Shipbuilding to be helpful. The full webinar is posted on the Gresham College website.

A big shout out to Rob Ossian’s Pirate Cove at www.thepirateking.com for the tremendous amount of research he shares so freely. I started by reading his “Quick and Dirty Seafaring Primer” and worked my way through his descriptions on navigation and weaponry. I even took a turn at his Ships & Boats Sailing Simulator.

Rob also responds to emails and provided answers to a few questions such as, “How many sailors would it take to tug down one of those water logged canvas sails during a rainstorm?” Because, of course, I did not wish to deprive my readers of a trans-Atlantic storm! They get to ride the dark black swells of water along with my gutsy protagonist Rose Payne and slide across the glassy decks of the Lyon drenched in sheeting rain.

I’ll close with a tiny synopsis of books one and two of the Lost Colony Series:

Breaking Ties unravels an ancient conspiracy over the murky course of a trans-Atlantic voyage plagued with trouble from day one. Rose Payne, the ship's clerk, is simply trying to outrun a broken heart and build a new life for herself in the New World. Instead, she runs straight into the arms of danger – pirates, plundering, and unexpected love.

Trail of Crosses quickly picks up where book one leaves off. Narrated by one of Rose’s best friends, Jane Mannering the huntress, we plunge into a story of teeth-gritting survival in the New World where cruelty and deception is the name of the game between tribes, that is, if you want them to keep a respectful distance. Alas, there is one legendary warrior Jane is not so sure she wants to remain at arm’s length. Read an excerpt from Trail of Crosses, coming soon from Astraea Press.

Please leave a comment and let me know what you think about the amazing recent discoveries concerning the fate of the Lost Colonists. Also, please take a moment to enter my Rafflecopter drawing for a chance to win a $10.00 Amazon or Barnes and Noble gift card (winner’s choice). Best wishes for winning!

Cheerio,

Jo

a Rafflecopter giveaway

BIO:

Jo is a mega reader of all genres and loves to indulge in marathon showings of Big Bang Theory, CSI, NCIS, and Castle. Her favorite books are full of rich history, Native Americans, and creatures from the otherworld – an occasional dragon, vampire, or time traveler. From St. Louis, Missouri, Jo moves a lot with her soldier husband. She has lived in the Midwest, the deep South, and now resides in Bavaria. Jo holds an M.B.A. and has served as a banker, college finance instructor, and high school business teacher. She is a PRO member of Romance Writers of America and From the Heart Romance Writers RWA Chapter.

Jo writes historical and paranormal romance. She is currently writing a series published by Astraea Press, which is based on the Lost Colonists of Roanoke Island – one of the world’s most intriguing unsolved mysteries.

CONTACT INFO:

Website: www.JoGrafford.com

FB: https://www.facebook.com/JoGraffordAu...

Twitter: @jografford

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/7360736.Jo_Grafford

Google+: https://plus.google.com/114780404475283292643/posts

YouTube Book Trailer: http://youtu.be/nBB8_qcG-9I

Highlighted Author: www.HighlightedAuthor.com

BUY LINKS:

Available at Amazon; Barnes and Noble; Smashwords; iBooks, and Astraea Press.

BLURB:

Portsmouth, England - April 26, 1587.

One hundred and fifteen colonists embark on a trans-Atlantic journey to build the glorious City of Raleigh. Unaware of the troubles already brewing, a young woman flies up the gangway at the last possible minute to join their ranks.

Was it fate?

Intelligent and well ahead of her times, Rose Payne's world is shattered after a secret betrothal to the duke’s son costs her job as a clerk in his father's household. Without a letter of recommendation, she becomes an easy target for recruiters to the Colonies. Desperate for work, she signs up for a risky overseas venture and sails for the New World, vowing never again fall for a wealthy gentleman.

Returning from a diplomatic tour in London, Chief Manteo is bewitched by the elusive, fiery-haired ship's clerk and determined to overcome her distrust. He contrives a daring plan to win her heart – a plan he prays will protect her from a chilling conspiracy involving murder, blood money, and a betrayal of their fledgling colony so terrifying it can only be revealed in Breaking Ties. Breaking Ties is the never-before-told rest of the story of the Lost Colony. It's a story of hope and sacrifice, love and betrayal, despair and tremendous courage of a group of pioneers who refused to quit when their lofty plans began to unravel...on day one.

~

The Lost Colony Series: How Much of It Is True?Jo Grafford

Before I became an author, I imagined writing fiction would be easy. I mean, you get to make everything up, right? Wrong! It took more than five years of research to write my debut historical, Breaking Ties, first book in the Lost Colony Series. Let me take you behind the scenes for a few minutes.

For 426 years, historians have debated the fate of the Lost Colonists. One of my all-time favorite books on the topic is Lee Miller’s Roanoke: Solving the Mystery of the Lost Colony. She builds a compelling case for internal sabotage of the City of Raleigh’s risky investment venture, which completely appealed to my background in banking and investing. Her claim started me on the path of asking, “What if?”

What if these brave men and women were not simply slaughtered en masse as so many historians have suggested? What if the truth was much less tidy, far more complex, and completely mind-boggling like reality so often is?

What if these brave men and women were not simply slaughtered en masse as so many historians have suggested? What if the truth was much less tidy, far more complex, and completely mind-boggling like reality so often is? In my quest for answers, I browsed original ship manifests and supply lists, read various period sailing journals, delved into church registries and library archives, and even took a road trip to visit Roanoke Island. I stood on the same patch of land the first English settlers assembled and imagined the craggy, overgrown terrain – barren of its current beach homes and boat docks – as their only welcome.

Then I started writing Breaking Ties nearly six years ago to try and piece together the “rest of the story” of these Lost Colonists – the never-been-told parts that occurred after all the official recordings of their journey stopped. This project was made easier when a news broke in October 2012 about a new clue concerning their fate.

In a nutshell, experts used laser technology to raise a patch on an original Lost Colony map, held for centuries at the British Museum. They uncovered the sketch of a fort located 50 miles inland where the Roanoke and Chowan Rivers converge. This location is an perfect match to one of the Lost Colonists' final statements to Governor John White (the last Englishman to see them alive) of their intent “to move 50 miles into the main[land].” This is the first clue produced that seems to offers conclusive evidence of survivors.

Fast-forward the clock to this past December. The First Colony Foundation employed radar and sonar technology to explore what lies beneath this patch. Their work is far from complete, but guess what? Already, they’ve discovered more exciting evidence that continues to support the underlying premise of my Lost Colony Series – that there were survivors!

author Jo GraffordThe Lost Colony Series is based on real people and real events. I even use the real names taken from the ship manifest. The novel also follows an accurate historical timeline. So where did I find the details to fill in all the missing pieces? It was a real treasure hunt, I assure you. John White’s journals and other writings only give us a shadowy glimpse of a day in the life of his shipmates aboard their fleet of three ships. I rounded out the depth of the characters, their background, and conversations in Breaking Ties with an enormous amount of digging through period books, paintings, sketches, and websites.

author Jo GraffordThe Lost Colony Series is based on real people and real events. I even use the real names taken from the ship manifest. The novel also follows an accurate historical timeline. So where did I find the details to fill in all the missing pieces? It was a real treasure hunt, I assure you. John White’s journals and other writings only give us a shadowy glimpse of a day in the life of his shipmates aboard their fleet of three ships. I rounded out the depth of the characters, their background, and conversations in Breaking Ties with an enormous amount of digging through period books, paintings, sketches, and websites.Since the Lyon – the largest of the three ships in my novel – was truly piloted by an ex-pirate, Simon Fernandez, I spent many hours researching famous pirates and pirate ships, pirate talk, and pirate weapons. Not only is it relevant to my story, it’s a darn lot of fun saying “Argh,” “Ahoy there, mate,” and “Shiver me timbers!”

Alas, the famous “Fifteen men on a dead man’s chest...Yo, ho, ho, and a bottle of rum,” is an excerpt from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, published in the 1800s. Since Breaking Ties is set in 1587, I had to dig further back in history for the seaman shanties I ended up using. I discovered the “gallowsbirds all, gallowsbirds all” shanty in a book titled The Mayflower by Kate Caffrey and Googled my way to the complete text online. This was chanted by the sailors like a mournful dirge to mask the cries of a certain young lad in Breaking Ties during his well-deserved but completely heart-wrenching flogging after a few of my colonists were pressed into sailing duty. To listen to some classic sea shanties online, see the Brethren of the Coast website.

To immerse myself fully in the rich flavor of 16th-century maritime life, I browsed the free text of The Elizabethan Sea Dogs by William Wood. I also found Dr. Ian Friel’s lecture about Elizabethan Merchant Ships and Shipbuilding to be helpful. The full webinar is posted on the Gresham College website.

To immerse myself fully in the rich flavor of 16th-century maritime life, I browsed the free text of The Elizabethan Sea Dogs by William Wood. I also found Dr. Ian Friel’s lecture about Elizabethan Merchant Ships and Shipbuilding to be helpful. The full webinar is posted on the Gresham College website. A big shout out to Rob Ossian’s Pirate Cove at www.thepirateking.com for the tremendous amount of research he shares so freely. I started by reading his “Quick and Dirty Seafaring Primer” and worked my way through his descriptions on navigation and weaponry. I even took a turn at his Ships & Boats Sailing Simulator.

Rob also responds to emails and provided answers to a few questions such as, “How many sailors would it take to tug down one of those water logged canvas sails during a rainstorm?” Because, of course, I did not wish to deprive my readers of a trans-Atlantic storm! They get to ride the dark black swells of water along with my gutsy protagonist Rose Payne and slide across the glassy decks of the Lyon drenched in sheeting rain.

I’ll close with a tiny synopsis of books one and two of the Lost Colony Series:

Breaking Ties unravels an ancient conspiracy over the murky course of a trans-Atlantic voyage plagued with trouble from day one. Rose Payne, the ship's clerk, is simply trying to outrun a broken heart and build a new life for herself in the New World. Instead, she runs straight into the arms of danger – pirates, plundering, and unexpected love.

Trail of Crosses quickly picks up where book one leaves off. Narrated by one of Rose’s best friends, Jane Mannering the huntress, we plunge into a story of teeth-gritting survival in the New World where cruelty and deception is the name of the game between tribes, that is, if you want them to keep a respectful distance. Alas, there is one legendary warrior Jane is not so sure she wants to remain at arm’s length. Read an excerpt from Trail of Crosses, coming soon from Astraea Press.

Please leave a comment and let me know what you think about the amazing recent discoveries concerning the fate of the Lost Colonists. Also, please take a moment to enter my Rafflecopter drawing for a chance to win a $10.00 Amazon or Barnes and Noble gift card (winner’s choice). Best wishes for winning!

Cheerio,

Jo

a Rafflecopter giveaway

BIO:

Jo is a mega reader of all genres and loves to indulge in marathon showings of Big Bang Theory, CSI, NCIS, and Castle. Her favorite books are full of rich history, Native Americans, and creatures from the otherworld – an occasional dragon, vampire, or time traveler. From St. Louis, Missouri, Jo moves a lot with her soldier husband. She has lived in the Midwest, the deep South, and now resides in Bavaria. Jo holds an M.B.A. and has served as a banker, college finance instructor, and high school business teacher. She is a PRO member of Romance Writers of America and From the Heart Romance Writers RWA Chapter.

Jo writes historical and paranormal romance. She is currently writing a series published by Astraea Press, which is based on the Lost Colonists of Roanoke Island – one of the world’s most intriguing unsolved mysteries.

CONTACT INFO:

Website: www.JoGrafford.com

FB: https://www.facebook.com/JoGraffordAu...

Twitter: @jografford

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/7360736.Jo_Grafford

Google+: https://plus.google.com/114780404475283292643/posts

YouTube Book Trailer: http://youtu.be/nBB8_qcG-9I

Highlighted Author: www.HighlightedAuthor.com

BUY LINKS:

Available at Amazon; Barnes and Noble; Smashwords; iBooks, and Astraea Press.

BLURB:

Portsmouth, England - April 26, 1587.

One hundred and fifteen colonists embark on a trans-Atlantic journey to build the glorious City of Raleigh. Unaware of the troubles already brewing, a young woman flies up the gangway at the last possible minute to join their ranks.

Was it fate?

Intelligent and well ahead of her times, Rose Payne's world is shattered after a secret betrothal to the duke’s son costs her job as a clerk in his father's household. Without a letter of recommendation, she becomes an easy target for recruiters to the Colonies. Desperate for work, she signs up for a risky overseas venture and sails for the New World, vowing never again fall for a wealthy gentleman.

Returning from a diplomatic tour in London, Chief Manteo is bewitched by the elusive, fiery-haired ship's clerk and determined to overcome her distrust. He contrives a daring plan to win her heart – a plan he prays will protect her from a chilling conspiracy involving murder, blood money, and a betrayal of their fledgling colony so terrifying it can only be revealed in Breaking Ties. Breaking Ties is the never-before-told rest of the story of the Lost Colony. It's a story of hope and sacrifice, love and betrayal, despair and tremendous courage of a group of pioneers who refused to quit when their lofty plans began to unravel...on day one.

Published on March 05, 2014 05:00

March 4, 2014

Small press spotlight: new and forthcoming historical novels, part 1

This post is the first of many galleries of historical novels I've assembled for Small Press Month. Additional installments will feature historical mysteries, university press titles, and novels from publishers outside the United States – all from small and independent presses.

A novel of intrigue, danger, and sexual politics, centering on a maid at the court of Ivan the Terrible in 16th-century Russia – an underutilized historical setting with a lot of dramatic potential. Jolly Fish Press, May 2014.

From an award-winning author of Regency romances and Western fiction comes this romantic historical novel, first in the Spanish Brand series, set in the royal Spanish colony of New Mexico in the 1780s. Camel Press, July 2013.

This literary historical novel about ambitious English anthropologists in 1930s Papua New Guinea is loosely based on the early life of Margaret Mead. Atlantic Monthly, June 2014.

This collection of dark stories of ghosts and the supernatural, set in the 18th and 19th centuries, was first translated into English last year. The author (not visible in this image) is Miyuki Miyabe. Haikasoru, November 2013.

An American woman of German descent faces prejudice and family strife in Nebraska farm country during the Great War. Red Hen Press, March 2014.

A story of survival; in southwestern Pennsylvania in the 1930s, the lives of the German wife of an Irish coal miner and their daughters are shaped by hardship and racial prejudice. St. Barbara is the patron saint of miners, and the title derives from townspeople's participation in an annual pageant dedicated to her. High Hill Press, August 2013.

Dramatic and darkly sensual historical fiction set in Florence in 1691, as a Sicilian sculptor struggles to fulfill his latest, near-impossible commission. Other Press, April 2014.

The newest historical novel from Shakespearean scholar Tiffany evokes the life of 17th-century poet Emilia Bassano Lanier, thought to be his Dark Lady from the Sonnets. Bagwyn, September 2013.

This historical lesbian-themed novel is set amid the world of anthropology in the American Southwest of the early 1920s, as a young Jewish woman from Brooklyn arrives in New Mexico to study on her own and finds her life transformed. Savvy Press, October 2013.

A novel of Choctaw life, centering on a young woman growing up in the company of her wise, eccentric relatives in Indian Territory in early 20th-century Oklahoma. The author is a member of the Choctaw Nation. Cinco Puntos Press, February 2014.

Mystery surrounds a young London seamstress who was employed by the royal family in Edwardian times. Decades later, in 2008, another young woman pieces together what happened to her after discovering a gorgeous quilt in an attic. Sourcebooks, May 2014.

This poetic historical novel set in medieval France lets readers follow the physical and spiritual journey of Robert of Arbrissel, the founder of Fontevraud Abbey, a haven for religious women.

Cuidono Press, November 2013.

A novel of intrigue, danger, and sexual politics, centering on a maid at the court of Ivan the Terrible in 16th-century Russia – an underutilized historical setting with a lot of dramatic potential. Jolly Fish Press, May 2014.

From an award-winning author of Regency romances and Western fiction comes this romantic historical novel, first in the Spanish Brand series, set in the royal Spanish colony of New Mexico in the 1780s. Camel Press, July 2013.

This literary historical novel about ambitious English anthropologists in 1930s Papua New Guinea is loosely based on the early life of Margaret Mead. Atlantic Monthly, June 2014.

This collection of dark stories of ghosts and the supernatural, set in the 18th and 19th centuries, was first translated into English last year. The author (not visible in this image) is Miyuki Miyabe. Haikasoru, November 2013.

An American woman of German descent faces prejudice and family strife in Nebraska farm country during the Great War. Red Hen Press, March 2014.

A story of survival; in southwestern Pennsylvania in the 1930s, the lives of the German wife of an Irish coal miner and their daughters are shaped by hardship and racial prejudice. St. Barbara is the patron saint of miners, and the title derives from townspeople's participation in an annual pageant dedicated to her. High Hill Press, August 2013.

Dramatic and darkly sensual historical fiction set in Florence in 1691, as a Sicilian sculptor struggles to fulfill his latest, near-impossible commission. Other Press, April 2014.

The newest historical novel from Shakespearean scholar Tiffany evokes the life of 17th-century poet Emilia Bassano Lanier, thought to be his Dark Lady from the Sonnets. Bagwyn, September 2013.

This historical lesbian-themed novel is set amid the world of anthropology in the American Southwest of the early 1920s, as a young Jewish woman from Brooklyn arrives in New Mexico to study on her own and finds her life transformed. Savvy Press, October 2013.

A novel of Choctaw life, centering on a young woman growing up in the company of her wise, eccentric relatives in Indian Territory in early 20th-century Oklahoma. The author is a member of the Choctaw Nation. Cinco Puntos Press, February 2014.

Mystery surrounds a young London seamstress who was employed by the royal family in Edwardian times. Decades later, in 2008, another young woman pieces together what happened to her after discovering a gorgeous quilt in an attic. Sourcebooks, May 2014.

This poetic historical novel set in medieval France lets readers follow the physical and spiritual journey of Robert of Arbrissel, the founder of Fontevraud Abbey, a haven for religious women.

Cuidono Press, November 2013.

Published on March 04, 2014 05:00

March 3, 2014

Book review: The Celestials, by Karen Shepard

In 1870, 75 young Chinese men board a train from California to North Adams, Massachusetts, to take jobs in Calvin Sampson’s shoe factory. He’s hired them to replace workers who went on strike, but they’re ignorant of this important fact. Taking its title from a period term for Chinese immigrants, The Celestials offers compassionate observations of how their presence transforms a small New England industrial town.

In 1870, 75 young Chinese men board a train from California to North Adams, Massachusetts, to take jobs in Calvin Sampson’s shoe factory. He’s hired them to replace workers who went on strike, but they’re ignorant of this important fact. Taking its title from a period term for Chinese immigrants, The Celestials offers compassionate observations of how their presence transforms a small New England industrial town. The novel’s premise is historically based, and on the surface, it may seem to recount an intriguing but rather obscure incident. However, Shepard takes care to demonstrate its importance without getting into lecture-mode. The triumph of Sampson’s “Chinese experiment” drew national attention to North Adams, affecting U.S. labor relations and immigration policy from that time forward.

Shepard interweaves the perspectives of many locals, from Sampson and his wife, Julia, to one of the young strikers and his sister, a recovering rape victim. The Celestials’ viewpoint focuses mainly on Charlie Sing, their English-speaking foreman, who simultaneously benefits and suffers from his role as a cultural bridge. The plot hums along with nervous tension: in this unusual situation, what will happen next? Many North Adams women organize a Sunday school for the Chinese men to encourage their assimilation into society, but when Julia Sampson gives birth to a half-Chinese baby, questions are raised about whether they’ve assimilated too well.

“How little we know of the hidden lives of those about us,” thinks Julia at one point. This theme is explored in many different ways, from Sampson’s insistence on photographing his new employees – a baffling concept to the Chinese, which they delightfully make their own later on – to the opposing reactions to one Chinese laborer’s Christian burial. Through the novel’s insightful characterizations, readers will get to know each of its unique individuals very well, in some instances even better than they know themselves.

The Celestials was published by Tin House Books in June 2013 ($15.95, trade pb, 361pp). Portland-based Tin House, which also produces a literary magazine, publishes a dozen books a year. This review first appeared in February's Historical Novels Review.

Published on March 03, 2014 07:00

March 1, 2014

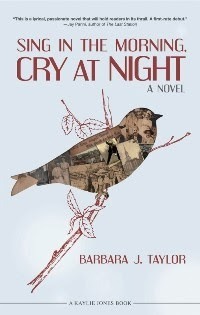

The Billy Sunday Snowstorm, a guest post by novelist Barbara J. Taylor

Today is the 100th anniversary of the "Billy Sunday Snowstorm," a significant event in the cultural history of Scranton, Pennsylvania – and in the lives of the characters in Barbara J. Taylor's forthcoming debut novel, Sing in the Morning, Cry at Night (Akashic/Kaylie Jones Books, July). I'm excited to be able to kick off my Small Press Month celebration with Barbara's beautifully written essay.

~ The Billy Sunday SnowstormBarbara J. Taylor

Little Billy Sunday’s come to our town to stay An’ drive the Devil out o’ here, an’ make him keep away. —Charles B. Stevens

The sign on Wyoming Avenue read, “Reverend William A. Sunday, the world’s greatest evangelist, will begin his siege on Scranton, March 1, 1914. Will you join his army?” Thousands of Christians from the Pennsylvania coal region eagerly awaited what promised to be the event of the year. Adherents admired Billy Sunday for his plain talk. “You don’t thrash the devil with highfalutin words,” he liked to say. They also appreciated his energetic style. Prior to becoming an evangelist, Sunday had played baseball for the Chicago White Stockings, and he brought that athleticism to his preaching. He was often seen throwing off his jacket and hitting an out-of-the-park homerun with his imaginary bat and ball to punctuate some bit of homespun wisdom.

Preparations for the revival started a year in advance. Per Sunday’s instructions, churches organized prayer meetings, added extra choir rehearsals, increased Sunday school membership, trained congregants to “witness for Christ,” and raised money to build one of Sunday’s tabernacles.

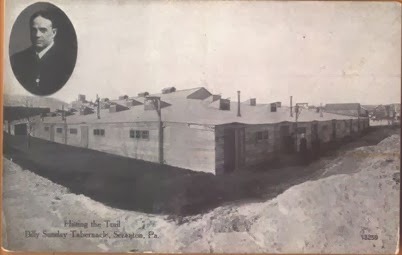

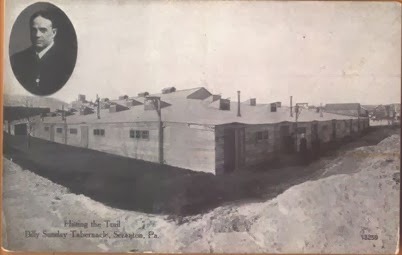

Exterior of Scranton Tabernacle, old postcard

Exterior of Scranton Tabernacle, old postcard

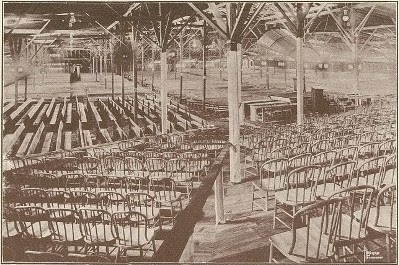

Completed on February 26th, the temporary structure could hold an audience of 10,000, plus another 1500 in the rear of the pulpit for choirs and dignitaries. From outside, the building looked like an organized shantytown, with its rough-hewn wood and abundant entrances. Windows dotted the four exterior walls and poked through the top of a turtleback roof designed to carry Sunday’s voice to every corner. Smoke curled from fifteen metal chimneys attached to the fifteen pot-bellied stoves installed to heat the main hall. Electric bulbs dangled from the rafters, lighting the seats and the sawdust-covered aisles below. Jury-rigged telephone lines and telegraph instruments surrounded the pulpit, guaranteeing quick reporting and extra editions of local newspapers.

Other preparations included newly built restrooms, first-aid stations, and a nursery at the local YWCA. “No children in arms,” according to Sunday who wanted to prevent distractions during the services. The evangelist also banned women’s hats and coughing so he could be seen and heard clearly.

It seemed Sunday planned for every eventuality except one. The weather.

March 1st began with clear skies, but as the day progressed a snowstorm moved in. The evangelist kicked off his seven-week campaign with three services that Sunday. When the evening sermon started, the streetcars were still operating thanks to plows attached to the fronts of the trolleys. While the snow accumulated outside, fourteen inches in all, Sunday continued preaching against such vices as drinking, gambling and tobacco use. Occasionally he’d have to pause and wait out the noise of the forty-five-mile-an-hour wind—“a real rip snorter,” as he called it—before continuing with his message. At one point he prayed, “God, get out there and grab that blizzard by the snout.” As always, Sunday ended the service by inviting those who wanted to be saved to come forward. He stood in front offering a “glad handshake” to anyone who “hit the sawdust trail” toward redemption.

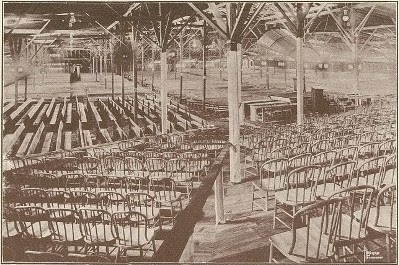

Interior of Scranton Tabernacle. Source: Ames History archive (public domain photo)

Interior of Scranton Tabernacle. Source: Ames History archive (public domain photo)

Once everyone had the opportunity to be saved, the reality of the storm set in. All modes of public transportation had ceased with 4000 worshipers inside the tabernacle. Snowdrifts, some ten feet high, blocked roads for miles. About 1500 people who lived nearby braved the harsh conditions and walked home, but the remaining 2500 would have to “camp in the house of God,” Sunday explained. The telegraph lines were down, but as luck would have it, the direct phone lines to the Scranton Times and the Tribune Republican were still working. Sunday took up an extra collection that night, this time for food and coal. Reporters called their respective papers and arranged for patrolmen a couple miles away to deliver fifty pounds of coffee, 500 loaves of bread, and 1000 sandwiches in their wagons. Three coal company workers braved raging winds and mountainous snowdrifts to deliver fuel to the tabernacle.

According to the papers, everyone who stayed passed the night without complaint. They boiled coffee on top of the stoves in the large, concave, collection plates, and had their fill of food. The next morning, when the winds had died down, volunteers showed up at the tabernacle in horse-drawn wagons and offered rides to the stranded. After calling the storm the worst he’d ever experienced, Sunday cancelled Monday’s services and declared a day of rest.

According to the papers, everyone who stayed passed the night without complaint. They boiled coffee on top of the stoves in the large, concave, collection plates, and had their fill of food. The next morning, when the winds had died down, volunteers showed up at the tabernacle in horse-drawn wagons and offered rides to the stranded. After calling the storm the worst he’d ever experienced, Sunday cancelled Monday’s services and declared a day of rest.

Growing up, the story of “The Billy Sunday Snowstorm,” as it came to be known, fascinated me. When people spoke of the event, they’d insist that all 2500 inside the tabernacle had no choice but to be saved after spending the night with such a charismatic preacher. And everyone knew somebody who had been saved. Even people my parents’ age, one generation removed from the event, claimed to have known at least one person who was stranded that night. My grandmother loved to tell how she was born during “The Billy Sunday Snowstorm” while her father was “off being saved.” Scrantonians still speak about their connections to the evangelist with great pride.

When I started writing, Sing in the Morning, Cry at Night, I knew I wanted to use the Billy Sunday story but I wasn’t sure how. As it turned out, two pivotal scenes in my novel take place that evening, one at the revival and one in the snowstorm. The tabernacle may be long gone, but a century later, Billy Sunday is still causing a stir in Scranton.

References:

Bruno, Guido. “Billy Sunday, Who Makes Religion Pay.” Pearson’s Magazine. April 1917: 323–332.

The Scranton Times. Various articles on Billy Sunday’s visit to Scranton. January–March 1914.

The Tribune-Republican. Various articles on Billy Sunday’s visit to Scranton. January–March 1914.

Author Bio

Barbara J. Taylor was born and raised in Scranton, PA, and teaches English in the Pocono Mountain School District. She has a master’s degree in creative writing from Wilkes University, and English and Education degrees from the University of Scranton. She still resides in “The Electric City,” two blocks away from where she grew up.

Barbara Taylor’s Sing in the Morning, Cry at Night, is being published by Kaylie Jones Books, an imprint of Akashic Books, on July 1, 2014. ($15.95, trade pb, 320pp). Visit the author's website at barbarajtaylor.com.

Brief summary of Sing in the Morning, Cry at Night

Almost everyone in town blames eight-year-old Violet for the death of her nine-year-old sister, Daisy. Sing in the Morning, Cry at Night opens on September 4, 1913, two months after the Fourth of July tragedy. Owen, the girls’ father, “turns to drink” and abandons his family. Their mother Grace falls victim to the seductive powers of Grief, an imagined figure who has seduced her off-and-on since childhood. Violet forms an unlikely friendship with Stanley Adamski, a motherless outcast who works in the mines as a breaker boy. During an unexpected blizzard, Grace goes into premature labor at home and is forced to rely on Violet, while Owen is “off being saved” at a Billy Sunday Revival. Inspired by a haunting family story, Sing in the Morning, Cry at Night blends real life incidents with fiction to show how grace can be found in the midst of tragedy.

Almost everyone in town blames eight-year-old Violet for the death of her nine-year-old sister, Daisy. Sing in the Morning, Cry at Night opens on September 4, 1913, two months after the Fourth of July tragedy. Owen, the girls’ father, “turns to drink” and abandons his family. Their mother Grace falls victim to the seductive powers of Grief, an imagined figure who has seduced her off-and-on since childhood. Violet forms an unlikely friendship with Stanley Adamski, a motherless outcast who works in the mines as a breaker boy. During an unexpected blizzard, Grace goes into premature labor at home and is forced to rely on Violet, while Owen is “off being saved” at a Billy Sunday Revival. Inspired by a haunting family story, Sing in the Morning, Cry at Night blends real life incidents with fiction to show how grace can be found in the midst of tragedy.

~ The Billy Sunday SnowstormBarbara J. Taylor

Little Billy Sunday’s come to our town to stay An’ drive the Devil out o’ here, an’ make him keep away. —Charles B. Stevens

The sign on Wyoming Avenue read, “Reverend William A. Sunday, the world’s greatest evangelist, will begin his siege on Scranton, March 1, 1914. Will you join his army?” Thousands of Christians from the Pennsylvania coal region eagerly awaited what promised to be the event of the year. Adherents admired Billy Sunday for his plain talk. “You don’t thrash the devil with highfalutin words,” he liked to say. They also appreciated his energetic style. Prior to becoming an evangelist, Sunday had played baseball for the Chicago White Stockings, and he brought that athleticism to his preaching. He was often seen throwing off his jacket and hitting an out-of-the-park homerun with his imaginary bat and ball to punctuate some bit of homespun wisdom.

Preparations for the revival started a year in advance. Per Sunday’s instructions, churches organized prayer meetings, added extra choir rehearsals, increased Sunday school membership, trained congregants to “witness for Christ,” and raised money to build one of Sunday’s tabernacles.

Exterior of Scranton Tabernacle, old postcard

Exterior of Scranton Tabernacle, old postcardCompleted on February 26th, the temporary structure could hold an audience of 10,000, plus another 1500 in the rear of the pulpit for choirs and dignitaries. From outside, the building looked like an organized shantytown, with its rough-hewn wood and abundant entrances. Windows dotted the four exterior walls and poked through the top of a turtleback roof designed to carry Sunday’s voice to every corner. Smoke curled from fifteen metal chimneys attached to the fifteen pot-bellied stoves installed to heat the main hall. Electric bulbs dangled from the rafters, lighting the seats and the sawdust-covered aisles below. Jury-rigged telephone lines and telegraph instruments surrounded the pulpit, guaranteeing quick reporting and extra editions of local newspapers.

Other preparations included newly built restrooms, first-aid stations, and a nursery at the local YWCA. “No children in arms,” according to Sunday who wanted to prevent distractions during the services. The evangelist also banned women’s hats and coughing so he could be seen and heard clearly.

It seemed Sunday planned for every eventuality except one. The weather.

March 1st began with clear skies, but as the day progressed a snowstorm moved in. The evangelist kicked off his seven-week campaign with three services that Sunday. When the evening sermon started, the streetcars were still operating thanks to plows attached to the fronts of the trolleys. While the snow accumulated outside, fourteen inches in all, Sunday continued preaching against such vices as drinking, gambling and tobacco use. Occasionally he’d have to pause and wait out the noise of the forty-five-mile-an-hour wind—“a real rip snorter,” as he called it—before continuing with his message. At one point he prayed, “God, get out there and grab that blizzard by the snout.” As always, Sunday ended the service by inviting those who wanted to be saved to come forward. He stood in front offering a “glad handshake” to anyone who “hit the sawdust trail” toward redemption.

Interior of Scranton Tabernacle. Source: Ames History archive (public domain photo)