Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 104

May 10, 2014

Murder at Mullings by Dorothy Cannell, first in a new cozy village mystery series set in '30s England

In this uneven debut entry in a new mystery series set in an English village in the ′20s and early ′30s, the first ominous note sounds at the end of chapter one. The nanny of Lord and Lady Stodmarsh’s orphaned grandson, Ned, is fired for drunkenness and mistreating her charge, and the family worries she’ll take revenge.

In this uneven debut entry in a new mystery series set in an English village in the ′20s and early ′30s, the first ominous note sounds at the end of chapter one. The nanny of Lord and Lady Stodmarsh’s orphaned grandson, Ned, is fired for drunkenness and mistreating her charge, and the family worries she’ll take revenge.Before then and for a good while after, though, background information on the characters and the estate of Mullings is thickly applied while the plot barely shuffles along, making the novel feel as mild-mannered and unexciting as the Stodmarshes, known for centuries in Dovecote Hatch for their “mopish propriety.” When the first death occurs, only Florence Norris, head housekeeper, guesses it was murder, but the lack of firm evidence prevents her from voicing her suspicions. Her loyalty to Ned, whom she had raised since birth, leads to her estrangement from pub owner George Bird, her potential love interest.

The story gains ground as more subplots involving Stodmarsh relatives, the caring and loyal Mullings servants, and their connections are introduced. When the elderly Lord Stodmarsh unwittingly brings a nefarious woman into his household, the resulting scandal really livens things up. Details on the peculiar aristocratic tradition of keeping an ornamental hermit add even more color. Overall, the book is more successful as a period saga than as a crime novel. It’s an enjoyable diversion, but hopefully future volumes will have improved pacing and a less passive sleuth.

Murder at Mullings was published in January by Severn House (£19.99/$28.95, library hardcover, 256pp). This review appeared in the Historical Novels Review's May issue as an online exclusive.

Published on May 10, 2014 13:04

May 8, 2014

Historical fiction picks at BEA 2014

Here's my annual post on the historical fiction picks at BookExpo America (BEA). Unlike last year, when I stayed home and regretted it, I’ll be heading to Manhattan at the end of May to meet up with other book enthusiasts, reacquaint myself with some favorite ethnic restaurants, and make my pilgrimage to the Strand.

For now, I'm basing my picks on BEA's list of autographing sessions, Publishers Weekly's "Galleys to Grab" focus (with a special thanks to my library for their institutional subscription), and publishers’ own BEA announcements. Updates welcome. This information is correct as far as I’m aware, but please cross-check these dates/times with the BEA site or program book to avoid possible disappointment.

Last updated: Thursday 5/8. New entries will be added regularly up until the show date, so please keep checking back! Look for ~new~ within this post later on to find recent additions.

~Galleys to Grab~

Algonquin (Booth 839)

Algonquin (Booth 839)

Lin Enger, The High Divide - a family's physical and emotional journey in the late 19th-century West.

Europa (Booth TM29 - in the Translation Market, at the far back, right side of the hall)

Elena Ferrante, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay - third installment in her Neapolitan Novels about the lives of two friends in '50s Italy.

Grove Atlantic (Booth 1321)

Malcolm Brooks, Painted Horses - a female archaeologist in '50s Montana.

Lily King, Euphoria - archaeologists in '30s New Guinea, inspired by the life of Margaret Mead.

Audrey Magee, The Undertaking - a marriage of convenience becomes something more in WWII-era Germany.

Hachette (Booth 2819)

Hachette (Booth 2819)

Laird Hunt, Neverhome - a farmer's wife fights for the Union during the US Civil War.

HarperCollins (Booth 2038)

Jessie Burton, The Miniaturist - love, obsession, art, and the secrets found within an unusual miniature house in 17th-century Amsterdam

Alix Christie, Gutenberg’s Apprentice - dramatizes the printing of the Gutenberg Bible in 15th-century Germany.

Katy Simpson Smith, The Story of Land and Sea - set in Revolutionary War-era North Carolina.

Macmillan (Booth 1738) - special giveaway times noted below.

Macmillan (Booth 1738) - special giveaway times noted below.

Kate Forsyth, Bitter Greens – Thursday 5/29, 2:30pm - places the fairy tale Rapunzel in the historical context of Renaissance Italy and interweaves it with the story of Charlotte-Rose de la Force, an early teller of the tale. [read my interview with Kate, based on the Australian edition]

Jo Walton, My Real Children – Friday 5/30, 10:30am - two different versions of modern history; speculative and historical fiction, both.

Ashley Weaver, Murder at the Brightwell – Friday 5/20, 2pm; also Saturday 5/31, 11:30am. Historical mystery set in the '30s.

Overlook (Booth 1546)

Rosie Thomas, The Illusionists - set amid the inner workings of the late Victorian world of theatrics and magic. Really enjoyed this one.

Penguin (Booth 1521)

Penguin (Booth 1521)

~new~ Alyson Richman, The Garden of Letters - a novel of love, tragedy, and war set in German-occupied Italy.

Sarah Waters, The Paying Guests - in '20s London, a widow and her spinster daughter take in lodgers who disrupt their lives.

Naomi Wood, Mrs. Hemingway - biographical fiction imagined from the viewpoints of the four very different women who were known by that name.

Random House (Booth 2839)

Amy Bloom, Lucky Us - two friends take a road trip across 1940s America.

Jane Smiley, Some Luck - an Iowa farm family's dreams, achievements, and tragedies, from post-WWI through the 1950s.

Simon & Schuster (Booth 2638-39)

Matthew Thomas, We Are Not Ourselves - multi-generational saga of an Irish-American family set in the postwar years.

Sourcebooks (Booth 921)

Sourcebooks (Booth 921)

Allegra Jordan, The End of Innocence - a WWI-era love story featuring two Harvard students.

Greer Macallister, The Magician's Lie - in turn-of-the-century Iowa, a female illusionist is accused of her husband's murder.

Turner (Booth 1168)

Gregg Loomis, The Cathar Secret - multi-period religious thriller.

Barbara Wood, Rainbows on the Moon - a missionary's wife in early 19th-century Hawaii.

WW Norton (Booth 1921)

Ann Hood, An Italian Wife - an Italian immigrant arrives in early 20th-century America in an arranged marriage; her decisions and their consequences.

~ Author Signings ~

Thursday 5/29

10-11am (Booth 3038, Harlequin)

10-11am (Booth 3038, Harlequin)

Pam Jenoff, The Winter Guest - love and family strife in WWII-era rural Poland.

11-11:30am (Booth 2939, Other Press)

Rupert Thomson, Secrecy - a dark novel of love, art, and intrigue in 17th-century Florence.

11:00–12:00 noon (Booth 839, Algonquin)

Lin Enger, The High Divide - See above under Galleys.

4-5pm, Table 13

Jo Walton, My Real Children - See above under Galleys.

Friday 5/30

10-11am (Booth 3038, Harlequin)

10-11am (Booth 3038, Harlequin)

Anne Girard, Madame Picasso - the great love story between Eva Gouel and Pablo Picasso in early 20th-century Europe. Girard is the pseudonym for historical novelist Diane Haeger.

10-10:30am (Booth 2946, Soho Press)

~new~ James R. Benn, The Rest Is Silence - 9th volume of the Billy Boyle WWII mystery series.

10:30-11am (Table 19)

Christina Baker Kline, Orphan Train - the bestselling novel about a surprising friendship, set in '30s America and today.

10:30-11am (Booth 1921, WW Norton)

Ann Hood, An Italian Wife - see above under Galleys.

10:45am (Booth 2557, Mystery Writers of America)

~new~ James R. Benn, The Rest Is Silence - see above under 10am slot.

11-11:30am (Booth 1321, Grove Atlantic)

Malcolm Brooks, Painted Horses - see above under Galleys.

11am-noon (Table 19)

11am-noon (Table 19)

Laird Hunt, Neverhome - see above under Galleys.

12-12:30pm (Table 7)

M.J. Rose, The Collector of Dying Breaths - suspenseful novel of reincarnation, poison and perfume in 16th-century Florence and in the present.

12-1pm (Booth 2917, Hachette)

Susan Jane Gilman, The Ice Cream Queen of Orchard Street - a Russian immigrant becomes a cunning entrepreneur in early 20th-century New York.

1-2pm (Booth 921, Sourcebooks)

Greer Macallister, The Magician’s Lie - See above under Galleys.

2-2:30pm (Table 8)

2-2:30pm (Table 8)

Lily King, Euphoria - See above under Galleys.

Saturday 5/31

10:45-11:15am (Booth 3038, Harlequin)

Anne Girard, Madame Picasso - see in Friday's listings.

For now, I'm basing my picks on BEA's list of autographing sessions, Publishers Weekly's "Galleys to Grab" focus (with a special thanks to my library for their institutional subscription), and publishers’ own BEA announcements. Updates welcome. This information is correct as far as I’m aware, but please cross-check these dates/times with the BEA site or program book to avoid possible disappointment.

Last updated: Thursday 5/8. New entries will be added regularly up until the show date, so please keep checking back! Look for ~new~ within this post later on to find recent additions.

~Galleys to Grab~

Algonquin (Booth 839)

Algonquin (Booth 839) Lin Enger, The High Divide - a family's physical and emotional journey in the late 19th-century West.

Europa (Booth TM29 - in the Translation Market, at the far back, right side of the hall)

Elena Ferrante, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay - third installment in her Neapolitan Novels about the lives of two friends in '50s Italy.

Grove Atlantic (Booth 1321)

Malcolm Brooks, Painted Horses - a female archaeologist in '50s Montana.

Lily King, Euphoria - archaeologists in '30s New Guinea, inspired by the life of Margaret Mead.

Audrey Magee, The Undertaking - a marriage of convenience becomes something more in WWII-era Germany.

Hachette (Booth 2819)

Hachette (Booth 2819)Laird Hunt, Neverhome - a farmer's wife fights for the Union during the US Civil War.

HarperCollins (Booth 2038)

Jessie Burton, The Miniaturist - love, obsession, art, and the secrets found within an unusual miniature house in 17th-century Amsterdam

Alix Christie, Gutenberg’s Apprentice - dramatizes the printing of the Gutenberg Bible in 15th-century Germany.

Katy Simpson Smith, The Story of Land and Sea - set in Revolutionary War-era North Carolina.

Macmillan (Booth 1738) - special giveaway times noted below.

Macmillan (Booth 1738) - special giveaway times noted below.Kate Forsyth, Bitter Greens – Thursday 5/29, 2:30pm - places the fairy tale Rapunzel in the historical context of Renaissance Italy and interweaves it with the story of Charlotte-Rose de la Force, an early teller of the tale. [read my interview with Kate, based on the Australian edition]

Jo Walton, My Real Children – Friday 5/30, 10:30am - two different versions of modern history; speculative and historical fiction, both.

Ashley Weaver, Murder at the Brightwell – Friday 5/20, 2pm; also Saturday 5/31, 11:30am. Historical mystery set in the '30s.

Overlook (Booth 1546)

Rosie Thomas, The Illusionists - set amid the inner workings of the late Victorian world of theatrics and magic. Really enjoyed this one.

Penguin (Booth 1521)

Penguin (Booth 1521)~new~ Alyson Richman, The Garden of Letters - a novel of love, tragedy, and war set in German-occupied Italy.

Sarah Waters, The Paying Guests - in '20s London, a widow and her spinster daughter take in lodgers who disrupt their lives.

Naomi Wood, Mrs. Hemingway - biographical fiction imagined from the viewpoints of the four very different women who were known by that name.

Random House (Booth 2839)

Amy Bloom, Lucky Us - two friends take a road trip across 1940s America.

Jane Smiley, Some Luck - an Iowa farm family's dreams, achievements, and tragedies, from post-WWI through the 1950s.

Simon & Schuster (Booth 2638-39)

Matthew Thomas, We Are Not Ourselves - multi-generational saga of an Irish-American family set in the postwar years.

Sourcebooks (Booth 921)

Sourcebooks (Booth 921)Allegra Jordan, The End of Innocence - a WWI-era love story featuring two Harvard students.

Greer Macallister, The Magician's Lie - in turn-of-the-century Iowa, a female illusionist is accused of her husband's murder.

Turner (Booth 1168)

Gregg Loomis, The Cathar Secret - multi-period religious thriller.

Barbara Wood, Rainbows on the Moon - a missionary's wife in early 19th-century Hawaii.

WW Norton (Booth 1921)

Ann Hood, An Italian Wife - an Italian immigrant arrives in early 20th-century America in an arranged marriage; her decisions and their consequences.

~ Author Signings ~

Thursday 5/29

10-11am (Booth 3038, Harlequin)

10-11am (Booth 3038, Harlequin)Pam Jenoff, The Winter Guest - love and family strife in WWII-era rural Poland.

11-11:30am (Booth 2939, Other Press)

Rupert Thomson, Secrecy - a dark novel of love, art, and intrigue in 17th-century Florence.

11:00–12:00 noon (Booth 839, Algonquin)

Lin Enger, The High Divide - See above under Galleys.

4-5pm, Table 13

Jo Walton, My Real Children - See above under Galleys.

Friday 5/30

10-11am (Booth 3038, Harlequin)

10-11am (Booth 3038, Harlequin)Anne Girard, Madame Picasso - the great love story between Eva Gouel and Pablo Picasso in early 20th-century Europe. Girard is the pseudonym for historical novelist Diane Haeger.

10-10:30am (Booth 2946, Soho Press)

~new~ James R. Benn, The Rest Is Silence - 9th volume of the Billy Boyle WWII mystery series.

10:30-11am (Table 19)

Christina Baker Kline, Orphan Train - the bestselling novel about a surprising friendship, set in '30s America and today.

10:30-11am (Booth 1921, WW Norton)

Ann Hood, An Italian Wife - see above under Galleys.

10:45am (Booth 2557, Mystery Writers of America)

~new~ James R. Benn, The Rest Is Silence - see above under 10am slot.

11-11:30am (Booth 1321, Grove Atlantic)

Malcolm Brooks, Painted Horses - see above under Galleys.

11am-noon (Table 19)

11am-noon (Table 19)Laird Hunt, Neverhome - see above under Galleys.

12-12:30pm (Table 7)

M.J. Rose, The Collector of Dying Breaths - suspenseful novel of reincarnation, poison and perfume in 16th-century Florence and in the present.

12-1pm (Booth 2917, Hachette)

Susan Jane Gilman, The Ice Cream Queen of Orchard Street - a Russian immigrant becomes a cunning entrepreneur in early 20th-century New York.

1-2pm (Booth 921, Sourcebooks)

Greer Macallister, The Magician’s Lie - See above under Galleys.

2-2:30pm (Table 8)

2-2:30pm (Table 8)Lily King, Euphoria - See above under Galleys.

Saturday 5/31

10:45-11:15am (Booth 3038, Harlequin)

Anne Girard, Madame Picasso - see in Friday's listings.

Published on May 08, 2014 12:00

May 7, 2014

Simon Sebag Montefiore's One Night in Winter, a tense evocation of Stalinist Russia

Sudden, mysterious arrests. Brutal interrogations. The crushing of any hint of antigovernment thought. Constant, stomach-churning terror.

Sudden, mysterious arrests. Brutal interrogations. The crushing of any hint of antigovernment thought. Constant, stomach-churning terror. Such is the reality of Stalinist Russia evoked so convincingly by Montefiore. As an acclaimed biographer and historian of the period, he has the oppressive atmosphere down cold. In his second novel, based on historical incidents, he heightens tension further by focusing on imaginative young people.

In 1945 Moscow, a group of teenagers, sons and daughters of the Bolshevik elite, act out a scene from their favorite romantic poet, Pushkin. When two are shot to death, the rest are accused of subversive activity. Their situation worsens when a velvet-covered notebook from their play-acting club is discovered.

The web of suspicion spirals outward to encompass their teachers and parents, who must feign approval of their children’s incarceration in the Lubyanka prison or face charges of party disloyalty. Stepping back, Montefiore then reveals two passionate affairs the participants have reason to conceal.

Some potentially intriguing individual stories remain underexplored, but overall, this is a gripping, fast-moving tale of love, fear, sacrifice, and survival.

One Night in Winter was published yesterday by Harper ($26.99, hardcover, 480pp). Century is the UK publisher. This review first appeared in Booklist's April 15th issue.

Published on May 07, 2014 08:00

May 5, 2014

A Historical Novelist's Confession, an essay by P.F. Chisholm

I'd like to welcome historical novelist Patricia Finney here today. Her most recent series includes six (thus far) historical mysteries featuring Elizabethan notable Sir Robert Carey, written under the name P.F. Chisholm. She has also shown her mastery of the era in a number of earlier novels, including Firedrake's Eye, Unicorn's Blood, and Gloriana's Torch, all exciting works of historical intrigue. Here she discusses an interpretation for one of her historical characters' lives which proved impossible to resist.

~

A Historical Novelist's ConfessionP.F. Chisholm

Anne Morgan, the first Lady Hunsdon, was the mother of my Elizabethan crime novel hero, Sir Robert Carey, and I owe her an apology.

He (and she) really existed. He was tall, dashing and a bit of a dandy, with a nice line in self-deprecating humour in his memoirs (Memoirs of the Earl of Monmouth, ed. F H Mares). And he was also the man who rode from London to Edinburgh in two and a half days to tell James VI of Scotland that he was now James I of England. You may even have read his touching account of Queen Elizabeth's last days. It was love at first sight when I first tripped over him in the wonderful book about the Anglo-Scottish Borders, George Macdonald Fraser's The Steel Bonnets. He was the perfect Elizabethan, and as GMF says, "Later generations of adventure story writers, who had never heard of Robert Carey, found it necessary to invent him." I simply picked him up and let him run.

His most recent adventure, An Air of Treason, has just come out with Poisoned Pen Press and finds him at Elizabeth's court, getting poisoned. This confession, however, is about the book before that, A Murder of Crows.

His most recent adventure, An Air of Treason, has just come out with Poisoned Pen Press and finds him at Elizabeth's court, getting poisoned. This confession, however, is about the book before that, A Murder of Crows.

You see, when I started writing stories about Sir Robert in the 1990s, the Internet was in its infancy, there was no Wikipedia – or it was filled with people who knew that Shakespeare was anybody except Shakespeare – and I found certain things very difficult to research, his mother being one of them. So I maintained a discreet silence.

Flash forward to a few years ago, when I started researching him again, and all was very different. At last I could track down my hero's mother.

There wasn't a lot, but it was an awful lot more than the pitiful listings I'd found in the '90s, usually giving the wrong number of children and occasionally mixing her up with her daughters-in-law.

Anne Morgan was probably born in 1529, making her only 16 at the time of her marriage to Henry Carey on 21st May 1545 when their marriage licence is dated. She was born in Arkestone, Herefordshire, daughter of Sir Thomas Morgan and Anne Whitney, of Welsh descent. She became Baroness Hunsdon on the 13 Jan 1559 when her husband was made Baron Hunsdon and she served the Queen as a Lady of the Privy Chamber. She had, according to the latest count, no fewer than twelve children, which argues an excellent constitution. John Dowland wrote a very pretty piece of music for her called "My Lady Hunsdon's Puffe." And she died on 19 Jan 1607, just over ten years after the death of her husband.

If you go to Westminster Abbey you can also find the splendidly vulgar tomb she organised for her husband in one of the first side chapels you come to: arguably the tomb is as big as the Queen's.

Here is exactly what you would expect: a respectable Elizabethan lady, who gave her husband a large number of children, some of whom died, as they did then, even if you were a Baroness. She served at Court and the rest of the time presumably settled at Hunsdon Hall in Hertfordshire and ran Hunsdon's estates for him.

So far so yawn. Yet I couldn't help noticing that her maiden name was Morgan and her sister married into the Trevannions of Caerhays Castle in Cornwall, within easy visiting distance of Arwenack House, Falmouth and the fascinating, deplorable Killigrews.

So far so yawn. Yet I couldn't help noticing that her maiden name was Morgan and her sister married into the Trevannions of Caerhays Castle in Cornwall, within easy visiting distance of Arwenack House, Falmouth and the fascinating, deplorable Killigrews.

The Killigrews were certainly pirates (sorry, privateers) as well as smugglers. Thanks to them, Falmouth was held in roughly the same esteem as the coast of Somalia is today. They appear to have had control of the Cornish Admiralty courts, and could and did flip a fig at anyone who thought they shouldn't menace the shipping all along the Channel and up into the Irish Sea. That's how Falmouth outgrew Penryn, which is a far older town.

There are tantalising legends about a woman called Kate Killigrew who went privateering in her later years. Was there only one or were there several women called Kate of that family? A Jane Killigrew gave Penryn town a loving cup to thank them for looking after her when she ran away from her husband. Any connection?

It was thin but very tempting. I'm a historical novelist, and I generally try to stick to the facts known about somebody. Here was a historical novelist's dilemma: do I go with the probable historical dullness of Anne Carey, Baroness Hunsdon – or do I have some fun with her?

Could I add her to the redoubtable band of post-menopausal ladies like Grainne O'Malley who seem to have gone a-roving in later life, as a sort of hobby? Like, oh, knitting with blood? Could my Anne have got herself a letter of marque to give a figleaf of legality to her raiding? Certainly, she had the contacts at Court to do it. Could she have got herself a ship and used it? Well, yes. A remarkable number of Elizabethan bigwigs made investments in ships. Of course I could. And so was born the redoubtable and appallingly embarrassing mother who turns up with her ship in London in A Murder of Crows and creates havoc.

I know I probably shouldn't have. But I couldn't help it.

~

P.F. Chisholm is a pseudonym for Patricia Finney, a well-known writer of historical thrillers, children's books, and nonfiction blogs and eBooks. Previous titles in the Sir Robert Carey and Sergeant Dodd series are A Famine of Horses, A Season of Knives, A Surfeit of Guns, A Plague of Angels, and A Murder of Crows. After the events in An Air of Treason, Sir Robert and Sergeant Dodd will be heading back to the Anglo-Scottish Border, where trouble is brewing as usual. Visit her website at www.patriciafinney.com.

~

A Historical Novelist's ConfessionP.F. Chisholm

Anne Morgan, the first Lady Hunsdon, was the mother of my Elizabethan crime novel hero, Sir Robert Carey, and I owe her an apology.

He (and she) really existed. He was tall, dashing and a bit of a dandy, with a nice line in self-deprecating humour in his memoirs (Memoirs of the Earl of Monmouth, ed. F H Mares). And he was also the man who rode from London to Edinburgh in two and a half days to tell James VI of Scotland that he was now James I of England. You may even have read his touching account of Queen Elizabeth's last days. It was love at first sight when I first tripped over him in the wonderful book about the Anglo-Scottish Borders, George Macdonald Fraser's The Steel Bonnets. He was the perfect Elizabethan, and as GMF says, "Later generations of adventure story writers, who had never heard of Robert Carey, found it necessary to invent him." I simply picked him up and let him run.

His most recent adventure, An Air of Treason, has just come out with Poisoned Pen Press and finds him at Elizabeth's court, getting poisoned. This confession, however, is about the book before that, A Murder of Crows.

His most recent adventure, An Air of Treason, has just come out with Poisoned Pen Press and finds him at Elizabeth's court, getting poisoned. This confession, however, is about the book before that, A Murder of Crows.You see, when I started writing stories about Sir Robert in the 1990s, the Internet was in its infancy, there was no Wikipedia – or it was filled with people who knew that Shakespeare was anybody except Shakespeare – and I found certain things very difficult to research, his mother being one of them. So I maintained a discreet silence.

Flash forward to a few years ago, when I started researching him again, and all was very different. At last I could track down my hero's mother.

There wasn't a lot, but it was an awful lot more than the pitiful listings I'd found in the '90s, usually giving the wrong number of children and occasionally mixing her up with her daughters-in-law.

Anne Morgan was probably born in 1529, making her only 16 at the time of her marriage to Henry Carey on 21st May 1545 when their marriage licence is dated. She was born in Arkestone, Herefordshire, daughter of Sir Thomas Morgan and Anne Whitney, of Welsh descent. She became Baroness Hunsdon on the 13 Jan 1559 when her husband was made Baron Hunsdon and she served the Queen as a Lady of the Privy Chamber. She had, according to the latest count, no fewer than twelve children, which argues an excellent constitution. John Dowland wrote a very pretty piece of music for her called "My Lady Hunsdon's Puffe." And she died on 19 Jan 1607, just over ten years after the death of her husband.

If you go to Westminster Abbey you can also find the splendidly vulgar tomb she organised for her husband in one of the first side chapels you come to: arguably the tomb is as big as the Queen's.

Here is exactly what you would expect: a respectable Elizabethan lady, who gave her husband a large number of children, some of whom died, as they did then, even if you were a Baroness. She served at Court and the rest of the time presumably settled at Hunsdon Hall in Hertfordshire and ran Hunsdon's estates for him.

So far so yawn. Yet I couldn't help noticing that her maiden name was Morgan and her sister married into the Trevannions of Caerhays Castle in Cornwall, within easy visiting distance of Arwenack House, Falmouth and the fascinating, deplorable Killigrews.

So far so yawn. Yet I couldn't help noticing that her maiden name was Morgan and her sister married into the Trevannions of Caerhays Castle in Cornwall, within easy visiting distance of Arwenack House, Falmouth and the fascinating, deplorable Killigrews. The Killigrews were certainly pirates (sorry, privateers) as well as smugglers. Thanks to them, Falmouth was held in roughly the same esteem as the coast of Somalia is today. They appear to have had control of the Cornish Admiralty courts, and could and did flip a fig at anyone who thought they shouldn't menace the shipping all along the Channel and up into the Irish Sea. That's how Falmouth outgrew Penryn, which is a far older town.

There are tantalising legends about a woman called Kate Killigrew who went privateering in her later years. Was there only one or were there several women called Kate of that family? A Jane Killigrew gave Penryn town a loving cup to thank them for looking after her when she ran away from her husband. Any connection?

It was thin but very tempting. I'm a historical novelist, and I generally try to stick to the facts known about somebody. Here was a historical novelist's dilemma: do I go with the probable historical dullness of Anne Carey, Baroness Hunsdon – or do I have some fun with her?

Could I add her to the redoubtable band of post-menopausal ladies like Grainne O'Malley who seem to have gone a-roving in later life, as a sort of hobby? Like, oh, knitting with blood? Could my Anne have got herself a letter of marque to give a figleaf of legality to her raiding? Certainly, she had the contacts at Court to do it. Could she have got herself a ship and used it? Well, yes. A remarkable number of Elizabethan bigwigs made investments in ships. Of course I could. And so was born the redoubtable and appallingly embarrassing mother who turns up with her ship in London in A Murder of Crows and creates havoc.

I know I probably shouldn't have. But I couldn't help it.

~

P.F. Chisholm is a pseudonym for Patricia Finney, a well-known writer of historical thrillers, children's books, and nonfiction blogs and eBooks. Previous titles in the Sir Robert Carey and Sergeant Dodd series are A Famine of Horses, A Season of Knives, A Surfeit of Guns, A Plague of Angels, and A Murder of Crows. After the events in An Air of Treason, Sir Robert and Sergeant Dodd will be heading back to the Anglo-Scottish Border, where trouble is brewing as usual. Visit her website at www.patriciafinney.com.

Published on May 05, 2014 05:00

May 3, 2014

The Bitter Trade: London’s Coffeehouses and the Glorious Revolution, essays by Piers Alexander and Dr. Matthew Green

As you sit back with a cup of caffeinated brew this Saturday, let's journey back in time to late 17th-century London, where the humble coffeehouse – a favorite hangout for creative types – was the place to be for provocative discussion and subversive activity. I'm grateful to novelist Piers Alexander and historian Dr. Matthew Green for contributing essays on this fascinating subject. Their jointly written post (the first of its type that I've published!) drew me into a richly described world I hadn't previously discovered and want to spend more time in.

I've just begun reading The Bitter Trade, Piers' new novel, and am enjoying it very much: its tense atmosphere of religious strife, intriguing characters, and colorful turns of phrase. His excerpt and essay will give readers a good taste for what's in store. I also plan to check out Matt's tours of the city's historic coffeehouses next time I'm in London. Please read on!

~

The Bitter Trade: London’s Coffeehouses

and the Glorious Revolution Piers Alexander and Dr Matthew Green

Coffee: A Revolutionary Drink

Piers Alexander

While researching The Bitter Trade, my novel set in England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688, I became fascinated with the role of coffeehouses in disrupting the pattern of society, thought and commerce. I like stories about underdogs and outsiders, and London in the late seventeenth century was one of the rare places when people could rise up through society if their wits were sharp and their spirits bold. The coffeehouses were central to this: unlicensed, threatening to the establishment (Charles II even briefly closed them all down), hotbeds of discussion and networking.

The Bitter Trade’s protagonist, Calumny Spinks, is a half-Huguenot redhead who is forced to make a fortune quickly to save his father’s life, and is drawn into the murky world of London coffee racketeering. He soon realises that greater forces are at work: coffeehouses in those days were used as an early postal system, and were riddled with spies and gossip. It was a particularly tense time, with the Dutch ruler, William of Orange, threatening to invade at any time and depose the unpopular Catholic King James II.

The Bitter Trade’s protagonist, Calumny Spinks, is a half-Huguenot redhead who is forced to make a fortune quickly to save his father’s life, and is drawn into the murky world of London coffee racketeering. He soon realises that greater forces are at work: coffeehouses in those days were used as an early postal system, and were riddled with spies and gossip. It was a particularly tense time, with the Dutch ruler, William of Orange, threatening to invade at any time and depose the unpopular Catholic King James II.

I am a coffee addict, and I happily followed the trail of coffee back through the Ottoman Empire to its roots as a mild drug used by Yemeni mystics to access the divine. I think it’s no accident that (independent!) coffeehouses are frequented by troublemakers, writers, app developers and trendsetters: coffee is a creative irritant. Brewed properly, it disturbs conventional thinking, brings strangers together, turns its back on consumerism and allows artists and revolutionaries to spend hours huddled over a little table for a tiny fee.

Not to say that all coffee is equal. I was lucky enough to go on one of Dr Matt Green’s walks around London’s lost coffeehouses. He is vehement about the difference between a mass market coffee chain and the kind of free-flowing, organic connections you can make in an independent coffeehouse. It’s a theme I love: that it’s better, like my protagonist Cal, to be poor, under threat, struggling, than to be part of the controlling cynical corporatisation of life. As I wrote the scene when he first enters a coffeehouse in defiance of his hardbitten Dissenting father, it brought back the feeling of coming to London as an eighteen-year-old: high on the stink and jostle and sensuality of it all.

Matt takes us on a whistlestop tour of coffeehouse history below: fuelled like all good stories by sex, lies and money. If the taste grabs you, I highly recommend reading The Lost World of the London Coffeehouse or – even better – joining him on a tour of the city’s coffeehouses and chocolate houses. As eye-opening as a triple espresso.

The Bitter Trade by Piers Alexander is available on all ebook stores.Paperback editions published June 2014 www.piersalexander.com

Black as Hell, Strong as Death, Sweet as Love

Dr Matthew Green

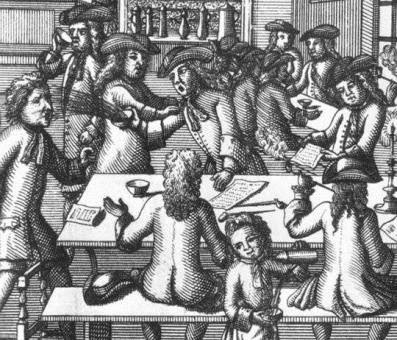

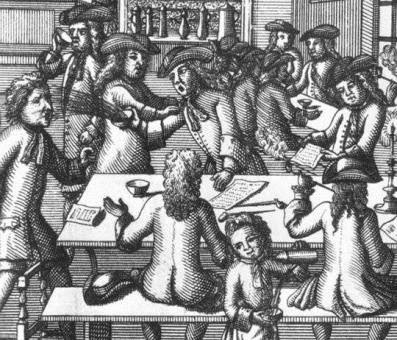

From the frontispiece of Ned Ward’s satirical poem Vulgus Brittanicus (1710)

From the frontispiece of Ned Ward’s satirical poem Vulgus Brittanicus (1710)

London’s coffee craze began in 1652 when Pasqua Rosée, the Greek servant of a coffee-loving British Levant merchant, opened London’s first coffeehouse (or rather, coffee shack) against the stone wall of St Michael’s churchyard in a labyrinth of alleys off Cornhill. Coffee was a smash hit; within a couple of years, Pasqua was selling over 600 dishes of coffee a day, to the horror of the local tavern keepers. For anyone who’s ever tried seventeenth-century style coffee, this can come as something of a shock — unless, that is, you like your brew “black as hell, strong as death, sweet as love”, as an old Turkish proverb recommends, and shot through with grit.

Early coffeehouses were smoky candlelit forums for commercial transactions, spirited debate, and the exchange of information, ideas, and lies. Customers sat around long communal tables strewn with every type of media imaginable listening in to each other’s conversations, interjecting whenever they pleased, and reflecting upon the newspapers. Talking to strangers, an alien concept in most coffee shops today, was actively encouraged. Much of the conversation centred upon news: as each new customer went in, they’d be assailed by cries of “What news have you?” or more formally, “Your servant, sir, what news from Tripoli?” or, if you were in the Latin Coffeehouse, “Quid Novi!” That coffeehouses functioned as post-boxes for many customers reinforced this news-gathering function. This was the Internet of its day, and it fuelled speculative bubbles in a way we’d find all too familiar.

Coffeehouse around 1700

Coffeehouse around 1700

Sex and Caffeine

No respectable women would have been seen dead in a coffeehouse. It wasn’t long before wives became frustrated at the amount of time their husbands were idling away “deposing princes, settling the bounds of kingdoms, and balancing the power of Europe with great justice and impartiality”, as Richard Steele put it in the Tatler, all from the comfort of a fireside bench. In 1674, years of simmering resentment erupted into the volcano of fury that was the Women’s Petition Against Coffee. The fair sex lambasted the “Excessive use of that Newfangled, Abominable, Heathenish Liquor called COFFEE” which, as they saw it, had reduced their virile industrious men into effeminate, babbling, French layabouts. Retaliation was swift and acerbic in the form of the vulgar Men’s Answer to the Women’s Petition Against Coffee, which claimed it was “base adulterate wine” and “muddy ale” that made men impotent. Coffee, in fact, was the Viagra of the day, making “the erection more vigorous, the ejaculation more full, add[ing] a spiritual ascendency to the sperm”.

Hogarth’s depiction of Moll and Tom King’s coffee-shack from The Four Times of Day (1736). Though it is early morning, the night has only just begun for the drunken rakes and prostitutes spilling out of the coffeehouse.

Strangled by transatlantic cables

Many of London’s coffeehouses were ultimately transformed into (less interesting) private members' clubs and were killed off by the twin threats of tea and the telegraph from the early nineteenth century. London's sole surviving eighteenth-century coffeehouse, the Baltic, closed its doors in 1866, a fortnight after a message had been successfully transmitted from London to New York via the transatlantic cable for the first time.

Dr Matthew Green graduated from Oxford University in 2011 with a PhD in the impact of the mass media in 18th-century London. He works as a writer, broadcaster, freelance journalist, and lecturer. He is the co-founder of Unreal City Audio (www.unrealcityaudio.co.uk), which produces immersive, critically-acclaimed tours of London as live events and audio downloads. His limited edition hand-sewn pamphlet, The Lost World of the London Coffeehouse, published by Idler Books, is on sale now: http://www.unrealcityaudio.co.uk/shop

He is currently writing The Time Traveller’s Guide to London, to be published by Penguin in March 2015.

I've just begun reading The Bitter Trade, Piers' new novel, and am enjoying it very much: its tense atmosphere of religious strife, intriguing characters, and colorful turns of phrase. His excerpt and essay will give readers a good taste for what's in store. I also plan to check out Matt's tours of the city's historic coffeehouses next time I'm in London. Please read on!

~

The Bitter Trade: London’s Coffeehouses

and the Glorious Revolution Piers Alexander and Dr Matthew Green

Coffee: A Revolutionary Drink

Piers Alexander

The serving-girl brought my coffee, and I lifted the dish to my nose as I had seen van Stijn do in the Moor’s Head. The smell was of dark earth, its spicy sting mixed with the soft womanly strength of soup on a cold day. It was as good as a lover’s first kiss. Its tendrils climbed under the skin of my face and smoothed out my frowns and aches.

I blew across the foamy brown surface and took a sip. My tongue burst into life. Stars sparkled in my eyes, and I could hear every throat-clearing and chair-scraping in the room.

“One shilling,” demanded the maid. A shilling for a teaspoonful of black dust?

- The Bitter Trade

While researching The Bitter Trade, my novel set in England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688, I became fascinated with the role of coffeehouses in disrupting the pattern of society, thought and commerce. I like stories about underdogs and outsiders, and London in the late seventeenth century was one of the rare places when people could rise up through society if their wits were sharp and their spirits bold. The coffeehouses were central to this: unlicensed, threatening to the establishment (Charles II even briefly closed them all down), hotbeds of discussion and networking.

The Bitter Trade’s protagonist, Calumny Spinks, is a half-Huguenot redhead who is forced to make a fortune quickly to save his father’s life, and is drawn into the murky world of London coffee racketeering. He soon realises that greater forces are at work: coffeehouses in those days were used as an early postal system, and were riddled with spies and gossip. It was a particularly tense time, with the Dutch ruler, William of Orange, threatening to invade at any time and depose the unpopular Catholic King James II.

The Bitter Trade’s protagonist, Calumny Spinks, is a half-Huguenot redhead who is forced to make a fortune quickly to save his father’s life, and is drawn into the murky world of London coffee racketeering. He soon realises that greater forces are at work: coffeehouses in those days were used as an early postal system, and were riddled with spies and gossip. It was a particularly tense time, with the Dutch ruler, William of Orange, threatening to invade at any time and depose the unpopular Catholic King James II. I am a coffee addict, and I happily followed the trail of coffee back through the Ottoman Empire to its roots as a mild drug used by Yemeni mystics to access the divine. I think it’s no accident that (independent!) coffeehouses are frequented by troublemakers, writers, app developers and trendsetters: coffee is a creative irritant. Brewed properly, it disturbs conventional thinking, brings strangers together, turns its back on consumerism and allows artists and revolutionaries to spend hours huddled over a little table for a tiny fee.

Not to say that all coffee is equal. I was lucky enough to go on one of Dr Matt Green’s walks around London’s lost coffeehouses. He is vehement about the difference between a mass market coffee chain and the kind of free-flowing, organic connections you can make in an independent coffeehouse. It’s a theme I love: that it’s better, like my protagonist Cal, to be poor, under threat, struggling, than to be part of the controlling cynical corporatisation of life. As I wrote the scene when he first enters a coffeehouse in defiance of his hardbitten Dissenting father, it brought back the feeling of coming to London as an eighteen-year-old: high on the stink and jostle and sensuality of it all.

Matt takes us on a whistlestop tour of coffeehouse history below: fuelled like all good stories by sex, lies and money. If the taste grabs you, I highly recommend reading The Lost World of the London Coffeehouse or – even better – joining him on a tour of the city’s coffeehouses and chocolate houses. As eye-opening as a triple espresso.

The Bitter Trade by Piers Alexander is available on all ebook stores.Paperback editions published June 2014 www.piersalexander.com

Black as Hell, Strong as Death, Sweet as Love

Dr Matthew Green

From the frontispiece of Ned Ward’s satirical poem Vulgus Brittanicus (1710)

From the frontispiece of Ned Ward’s satirical poem Vulgus Brittanicus (1710)London’s coffee craze began in 1652 when Pasqua Rosée, the Greek servant of a coffee-loving British Levant merchant, opened London’s first coffeehouse (or rather, coffee shack) against the stone wall of St Michael’s churchyard in a labyrinth of alleys off Cornhill. Coffee was a smash hit; within a couple of years, Pasqua was selling over 600 dishes of coffee a day, to the horror of the local tavern keepers. For anyone who’s ever tried seventeenth-century style coffee, this can come as something of a shock — unless, that is, you like your brew “black as hell, strong as death, sweet as love”, as an old Turkish proverb recommends, and shot through with grit.

Early coffeehouses were smoky candlelit forums for commercial transactions, spirited debate, and the exchange of information, ideas, and lies. Customers sat around long communal tables strewn with every type of media imaginable listening in to each other’s conversations, interjecting whenever they pleased, and reflecting upon the newspapers. Talking to strangers, an alien concept in most coffee shops today, was actively encouraged. Much of the conversation centred upon news: as each new customer went in, they’d be assailed by cries of “What news have you?” or more formally, “Your servant, sir, what news from Tripoli?” or, if you were in the Latin Coffeehouse, “Quid Novi!” That coffeehouses functioned as post-boxes for many customers reinforced this news-gathering function. This was the Internet of its day, and it fuelled speculative bubbles in a way we’d find all too familiar.

Coffeehouse around 1700

Coffeehouse around 1700Sex and Caffeine

No respectable women would have been seen dead in a coffeehouse. It wasn’t long before wives became frustrated at the amount of time their husbands were idling away “deposing princes, settling the bounds of kingdoms, and balancing the power of Europe with great justice and impartiality”, as Richard Steele put it in the Tatler, all from the comfort of a fireside bench. In 1674, years of simmering resentment erupted into the volcano of fury that was the Women’s Petition Against Coffee. The fair sex lambasted the “Excessive use of that Newfangled, Abominable, Heathenish Liquor called COFFEE” which, as they saw it, had reduced their virile industrious men into effeminate, babbling, French layabouts. Retaliation was swift and acerbic in the form of the vulgar Men’s Answer to the Women’s Petition Against Coffee, which claimed it was “base adulterate wine” and “muddy ale” that made men impotent. Coffee, in fact, was the Viagra of the day, making “the erection more vigorous, the ejaculation more full, add[ing] a spiritual ascendency to the sperm”.

Hogarth’s depiction of Moll and Tom King’s coffee-shack from The Four Times of Day (1736). Though it is early morning, the night has only just begun for the drunken rakes and prostitutes spilling out of the coffeehouse.

Strangled by transatlantic cables

Many of London’s coffeehouses were ultimately transformed into (less interesting) private members' clubs and were killed off by the twin threats of tea and the telegraph from the early nineteenth century. London's sole surviving eighteenth-century coffeehouse, the Baltic, closed its doors in 1866, a fortnight after a message had been successfully transmitted from London to New York via the transatlantic cable for the first time.

Dr Matthew Green graduated from Oxford University in 2011 with a PhD in the impact of the mass media in 18th-century London. He works as a writer, broadcaster, freelance journalist, and lecturer. He is the co-founder of Unreal City Audio (www.unrealcityaudio.co.uk), which produces immersive, critically-acclaimed tours of London as live events and audio downloads. His limited edition hand-sewn pamphlet, The Lost World of the London Coffeehouse, published by Idler Books, is on sale now: http://www.unrealcityaudio.co.uk/shop

He is currently writing The Time Traveller’s Guide to London, to be published by Penguin in March 2015.

Published on May 03, 2014 04:30

May 1, 2014

The Secret Garden, Rapunzel, and The Milky Way: Books and a Tale That Shaped My Characters, an essay by Ann Weisgarber

It's an honor to be hosting Ann Weisgarber on my blog today. She has written two historical novels that have been garnering accolades: The Promise, shortlisted for the 2014 Walter Scott Prize; and The Personal History of Rachel DuPree (see my earlier interview with Ann), which won the 2010 Langum Prize for Historical Fiction. Ann has contributed a wonderful essay on a topic that I'm sure will resonate as strongly with you as it did with me: her own and her characters' love of reading.

~

The Secret Garden, Rapunzel, and The Milky Way:

Books and a Tale That Shaped My Characters Ann Weisgarber

I read every chance I get and often carry a book with me. I read while I’m in line at the post office and when running the car through the car wash. Without a book, I’m the proverbial lost lamb desperately looking for something, anything, to read. Instructions on post office forms will do in a pinch. So will the car owner’s manual.

If reading means this much to me, then surely it’s important to my characters.

In my first novel, The Personal History of Rachel DuPree, the narrator, Rachel, lives with her family on an isolated ranch in the South Dakota Badlands. It takes place in 1917 and her life, like many ranch women’s, calls for hard work. Money is tight and books are an extravagant luxury. Yet, while writing the story, I wanted books to be part of Rachel’s life. All I had to do was figure out how she acquired them.

In my first novel, The Personal History of Rachel DuPree, the narrator, Rachel, lives with her family on an isolated ranch in the South Dakota Badlands. It takes place in 1917 and her life, like many ranch women’s, calls for hard work. Money is tight and books are an extravagant luxury. Yet, while writing the story, I wanted books to be part of Rachel’s life. All I had to do was figure out how she acquired them.

I considered various ideas – second-hand books sold at the general store, a neighbor woman sharing her books with Rachel – but those didn’t push the story forward. Then, one afternoon I picked up my copy of The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett. I read the inscription. To Ann with love from Mom. Mom was my grandmother. She gave me the book when I was nine.

Of course. The answer was Rachel’s mother-in-law, Mrs. DuPree, who lived in Chicago. She’d send a book to each of her grandchildren at the time of their births. This allowed me to show Mrs. DuPree’s relationship with her grandchildren, but just as important, I could use the books to say something about Rachel’s situation. Following this reasoning, in Chapter Two, Rachel tucks her children into bed and reads Rapunzel from a book of fairy tales Mrs. DuPree had sent when a child, now deceased, was born. This story about a woman locked in a tower waiting for rescue is a parallel story to Rachel’s life except Rachel eventually realizes she must rescue herself.

Books are also in The Promise, my latest novel that takes place in 1900 in Galveston, Texas. One of the narrators is Catherine Wainwright, a pianist caught in the midst of a scandal. She has a college education so it’s logical that she owns books. It’s also logical that when Catherine is shunned by family and friends, she turns to books for comfort. However, in Chapter Two she says, “I …. tried to read my favorite novels, but the stories that once enthralled now unnerved me.”

Although not stated, in my mind’s eye, these novels include Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. Both remind Catherine what happens to women who break social norms, and her desperation increases.

Although not stated, in my mind’s eye, these novels include Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. Both remind Catherine what happens to women who break social norms, and her desperation increases.

Later, in Chapter Seven, Nan Ogden, the other narrator, refers to the one book that her employer, Oscar Williams, owns and keeps on a parlor table. The title is The Milky Way and includes illustrations of the galaxy. It’s an actual book published in 1883 that I have on my book shelf. Here’s what Nan says about it.

“I never could see the need for that book of his, not when the stars are right overhead, night after night, easier to look at than all that bitty print in a book. But that was Oscar for you, he liked to read.”

Those sentences, I hope, show something about Nan’s and Oscar’s characters and interests. They also imply why Oscar doesn’t see Nan as a suitable marriage partner even though she’s raising his son and as he puts it, “I am in need of a wife.”

Oscar’s The Milky Way reappears in Chapter Eleven when Catherine reads underlined passages that refer to “the truth.” Realizing this is so important to Oscar that he’s marked the lines, Catherine panics. She hasn’t told him about the scandal. Alarmed, this sets off a chain of behavior that reflects her determination to bury the past. In the last chapter, lives are changed, but Oscar’s and Catherine’s books are saved. They’re kept for the future when times are better. The stories will again enthrall and perhaps unnerve the characters.

I include books in my novels to help reveal character and to push the stories forward. But it’s fair to say that books do the same for those of us who are readers. We connect to specific eras, certain settings, and types of narrators. Stories make us snap to and see something about ourselves. They inspire us, guide us, and yes, sometimes they frighten us. Books help shape us, and that is the enduring gift of the written word.

~

Photo credit: Christine MeekerAnn Weisgarber's first novel was the critically acclaimed The Personal History of Rachel DuPree. She was nominated for England’s 2009 Orange Prize and for the 2009 Orange Award for New Writers. In the United States, she won the Stephen Turner Award for New Fiction and the Langum Prize for American Historical Fiction. She was shortlisted for the Ohioana Book Award and was a Barnes and Noble Discover New Writer.

Photo credit: Christine MeekerAnn Weisgarber's first novel was the critically acclaimed The Personal History of Rachel DuPree. She was nominated for England’s 2009 Orange Prize and for the 2009 Orange Award for New Writers. In the United States, she won the Stephen Turner Award for New Fiction and the Langum Prize for American Historical Fiction. She was shortlisted for the Ohioana Book Award and was a Barnes and Noble Discover New Writer.

Her new novel, The Promise (Skyhorse Publishing, April 2014) is shortlisted for the UK’s Walter Scott Prize in Historical Fiction and is a Spur Award finalist in the United States. Ann serves on the selection committee for the Langum Prize in American Historical Fiction. She divides her time between Sugar Land, TX and Galveston, TX. Her website is http://annweisgarber.com.

~

The Secret Garden, Rapunzel, and The Milky Way:

Books and a Tale That Shaped My Characters Ann Weisgarber

I read every chance I get and often carry a book with me. I read while I’m in line at the post office and when running the car through the car wash. Without a book, I’m the proverbial lost lamb desperately looking for something, anything, to read. Instructions on post office forms will do in a pinch. So will the car owner’s manual.

If reading means this much to me, then surely it’s important to my characters.

In my first novel, The Personal History of Rachel DuPree, the narrator, Rachel, lives with her family on an isolated ranch in the South Dakota Badlands. It takes place in 1917 and her life, like many ranch women’s, calls for hard work. Money is tight and books are an extravagant luxury. Yet, while writing the story, I wanted books to be part of Rachel’s life. All I had to do was figure out how she acquired them.

In my first novel, The Personal History of Rachel DuPree, the narrator, Rachel, lives with her family on an isolated ranch in the South Dakota Badlands. It takes place in 1917 and her life, like many ranch women’s, calls for hard work. Money is tight and books are an extravagant luxury. Yet, while writing the story, I wanted books to be part of Rachel’s life. All I had to do was figure out how she acquired them. I considered various ideas – second-hand books sold at the general store, a neighbor woman sharing her books with Rachel – but those didn’t push the story forward. Then, one afternoon I picked up my copy of The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett. I read the inscription. To Ann with love from Mom. Mom was my grandmother. She gave me the book when I was nine.

Of course. The answer was Rachel’s mother-in-law, Mrs. DuPree, who lived in Chicago. She’d send a book to each of her grandchildren at the time of their births. This allowed me to show Mrs. DuPree’s relationship with her grandchildren, but just as important, I could use the books to say something about Rachel’s situation. Following this reasoning, in Chapter Two, Rachel tucks her children into bed and reads Rapunzel from a book of fairy tales Mrs. DuPree had sent when a child, now deceased, was born. This story about a woman locked in a tower waiting for rescue is a parallel story to Rachel’s life except Rachel eventually realizes she must rescue herself.

Books are also in The Promise, my latest novel that takes place in 1900 in Galveston, Texas. One of the narrators is Catherine Wainwright, a pianist caught in the midst of a scandal. She has a college education so it’s logical that she owns books. It’s also logical that when Catherine is shunned by family and friends, she turns to books for comfort. However, in Chapter Two she says, “I …. tried to read my favorite novels, but the stories that once enthralled now unnerved me.”

Although not stated, in my mind’s eye, these novels include Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. Both remind Catherine what happens to women who break social norms, and her desperation increases.

Although not stated, in my mind’s eye, these novels include Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. Both remind Catherine what happens to women who break social norms, and her desperation increases. Later, in Chapter Seven, Nan Ogden, the other narrator, refers to the one book that her employer, Oscar Williams, owns and keeps on a parlor table. The title is The Milky Way and includes illustrations of the galaxy. It’s an actual book published in 1883 that I have on my book shelf. Here’s what Nan says about it.

“I never could see the need for that book of his, not when the stars are right overhead, night after night, easier to look at than all that bitty print in a book. But that was Oscar for you, he liked to read.”

Those sentences, I hope, show something about Nan’s and Oscar’s characters and interests. They also imply why Oscar doesn’t see Nan as a suitable marriage partner even though she’s raising his son and as he puts it, “I am in need of a wife.”

Oscar’s The Milky Way reappears in Chapter Eleven when Catherine reads underlined passages that refer to “the truth.” Realizing this is so important to Oscar that he’s marked the lines, Catherine panics. She hasn’t told him about the scandal. Alarmed, this sets off a chain of behavior that reflects her determination to bury the past. In the last chapter, lives are changed, but Oscar’s and Catherine’s books are saved. They’re kept for the future when times are better. The stories will again enthrall and perhaps unnerve the characters.

I include books in my novels to help reveal character and to push the stories forward. But it’s fair to say that books do the same for those of us who are readers. We connect to specific eras, certain settings, and types of narrators. Stories make us snap to and see something about ourselves. They inspire us, guide us, and yes, sometimes they frighten us. Books help shape us, and that is the enduring gift of the written word.

~

Photo credit: Christine MeekerAnn Weisgarber's first novel was the critically acclaimed The Personal History of Rachel DuPree. She was nominated for England’s 2009 Orange Prize and for the 2009 Orange Award for New Writers. In the United States, she won the Stephen Turner Award for New Fiction and the Langum Prize for American Historical Fiction. She was shortlisted for the Ohioana Book Award and was a Barnes and Noble Discover New Writer.

Photo credit: Christine MeekerAnn Weisgarber's first novel was the critically acclaimed The Personal History of Rachel DuPree. She was nominated for England’s 2009 Orange Prize and for the 2009 Orange Award for New Writers. In the United States, she won the Stephen Turner Award for New Fiction and the Langum Prize for American Historical Fiction. She was shortlisted for the Ohioana Book Award and was a Barnes and Noble Discover New Writer.Her new novel, The Promise (Skyhorse Publishing, April 2014) is shortlisted for the UK’s Walter Scott Prize in Historical Fiction and is a Spur Award finalist in the United States. Ann serves on the selection committee for the Langum Prize in American Historical Fiction. She divides her time between Sugar Land, TX and Galveston, TX. Her website is http://annweisgarber.com.

Published on May 01, 2014 06:04

April 29, 2014

A special Downton-themed giveaway for US readers

I'm running a special giveaway for blog readers. Up for grabs is a brand new hardcover of Judith Lennox's latest novel One Last Dance (Headline, 2014), open to those in the US. Please fill out the form below for a chance to win.

I'm running a special giveaway for blog readers. Up for grabs is a brand new hardcover of Judith Lennox's latest novel One Last Dance (Headline, 2014), open to those in the US. Please fill out the form below for a chance to win.This is an unusual circumstance because I haven't read the novel myself (yet), but it's described as "for fans of Downton Abbey and My Last Duchess." It tells the story of Esme Reddaway, whose life spans most of the 20th century, as she tries to uncover secrets dating from the WWI years. The plot deals with sibling rivalry, revenge, a failed love affair, and a neglected English house called Rosindell. Some of you may recognize the cover, too. More on Goodreads here.

Obviously, this is all very trendy, but Judith Lennox has been writing this type of multi-generational English saga for decades, long before the Crawleys were even a whisper of an idea.

Here's the story: I've been reading and enjoying her novels for a long time, so when I learned she had a new one out, I pounced right on Amazon and ordered a copy from a UK bookseller. Three weeks and $18 or so later, a brand spanking new trade paperback arrived in the mail.

Then, two days after that, I was out in Columbus, Ohio, for the semiannual meeting of the Great Lakes Historical Novel Society chapter and stopped by a Half Price Books store. And, wouldn't you know it, sitting in the clearance section was a spotless hardcover copy of the same book, priced at $2. It appears to be unread. What were the chances? Anyway, this is the copy I'm giving away. I bought it because it was a rare find in these parts, and because I knew one of you would be able to give it a good home.

Since it's not available for sale in the US and it's a large and heavy book (and with apologies to everyone else), I'm limiting this giveaway to readers in the United States. One entry per person, please. The deadline will be Friday, May 9th. Good luck!

Loading...

Published on April 29, 2014 17:54

April 28, 2014

An interview with Phyllis T. Smith, author of I Am Livia

I'm excited to bring you this interview with Phyllis T. Smith, whose debut novel releases this Thursday, May 1st. I Am Livia is a smoothly engaging account of Livia Drusilla, who became the renowned and reviled first empress of Rome as the wife of Caesar Augustus. Speaking in a clear, honest voice, she sets the record straight by revealing her story: her early life as the daughter of the Roman aristocracy, her arranged first marriage to Tiberius Nero, her unexpected attraction to Rome's ambitious young emperor, and much more. No previous knowledge of the personalities and complex politics of the era is needed, since all of the details are well explained. Readers who seek out fiction about intelligent, powerful women of the past will find a great deal to enjoy here – I definitely did!

What draws you to ancient Rome as a setting?

I remember as a child loving Rosemary Sutcliff’s novels set in Roman Britain. Later, I enjoyed I Claudius (both the book and the TV miniseries), which introduced me to Livia as a fictional villain. In college, I took a wonderful classical civilization course that exposed me to Plutarch’s Lives. The high drama of Roman history just spoke to me. Then, too, I’m struck by how in the later years of the Republic the Romans were dealing with problems that might have some parallels today. Reading Cicero’s correspondence, I feel much closer to him than I do to medieval kings when I read primary source material about them. From his letters, he could almost be a modern politician. But of course he wasn’t that. The Romans lived in a world which was similar to ours in some ways, but also profoundly different, which is what makes them so fascinating.

I remember as a child loving Rosemary Sutcliff’s novels set in Roman Britain. Later, I enjoyed I Claudius (both the book and the TV miniseries), which introduced me to Livia as a fictional villain. In college, I took a wonderful classical civilization course that exposed me to Plutarch’s Lives. The high drama of Roman history just spoke to me. Then, too, I’m struck by how in the later years of the Republic the Romans were dealing with problems that might have some parallels today. Reading Cicero’s correspondence, I feel much closer to him than I do to medieval kings when I read primary source material about them. From his letters, he could almost be a modern politician. But of course he wasn’t that. The Romans lived in a world which was similar to ours in some ways, but also profoundly different, which is what makes them so fascinating.

In your author's note, you mention that Livia is thought to be the most powerful woman in the history of ancient Rome. How much did this play into your decision to choose her as a subject?

It was a big part of my decision because I’m interested in women in politics. For most of recorded history, women have been limited to exerting influence through their relationships with powerful men. Now in many places they’re coming into their own and are increasingly holding high public office. I’m gripped by the question of what that means for the world; I certainly hope it means something good. There is evidence that Livia used her influence to make Caesar Octavianus’s rule more benign. She ultimately paid a price, in being defamed by some Roman historians who didn’t like the idea of a powerful woman.

It’s surprising how much Livia acted like a modern first lady, with her charitable activities and her going to comfort disaster victims. She had to project an image of ideal Roman domesticity, while helping to run an empire. The concern with a family-oriented image seems very modern. So in the book I was able to play with this question: What is different now and what is the same?

You present Caesar Octavianus from a viewpoint that readers don't normally see. What more did you discover about him as a character when envisioning him through Livia's eyes?

Caesar Octavianus knew how to be ruthless in public life. But there is no way to make his behavior with Livia psychologically comprehensible unless you assume he was capable of deep human emotions, including love. Looking at him through Livia’s eyes, I could see him as someone plunged as a teenager into a viper’s nest—Roman politics at that time. Not that he deserves a moral pass, but he lived in a harsh world. In the book, Livia sees all the ways in which he is vulnerable, including the fact that when he goes out to fight a battle there’s no guarantee that he’ll win or even survive.

The scene in which Tiberius Nero and his pregnant wife Livia invite Caesar to a dinner party at their home was one of my favorites, not just because it brings so many strong personalities together for a social event but also because it reveals new sides to everyone's character. Was it as enjoyable to write as it was to read?

I love hearing that you liked that scene! It was very enjoyable to write. In particular, I got a kick out of weaving in mythology. I knew that Caesar in later years tried to write a tragic play about Ajax, the warrior in the Iliad. (He decided he had no talent and threw the play away.) I wondered why he picked Ajax of all people as his tragic hero. No biography I read explained that. But in the Iliad I came across Ajax’s prayer for light on the field of battle. This fit in well with Caesar’s recorded reverence for Apollo, god of light and knowledge. In the dinner party scene, Caesar talks about Ajax, and people speak revealingly about their favorite deities. Meanwhile, the attraction between Caesar and Livia begins to sizzle, and that was fun to show.

author Phyllis T. SmithI thought you did an excellent job bringing a human dimension to many iconic figures from the period. Were any of them more of a challenge to relate to, or to re-create on the page, than others?

author Phyllis T. SmithI thought you did an excellent job bringing a human dimension to many iconic figures from the period. Were any of them more of a challenge to relate to, or to re-create on the page, than others?

Mark Antony was hard to relate to. I just didn’t like him much! Not because his love affair with Cleopatra made his wife Octavia’s life unpleasant, though it certainly did. But because he was gratuitously brutal and did things like ordering Cicero’s head and hands cut off in revenge for his oratory. I found Antony’s indifference to his supporters during the Perusian War repellent, too. His brother, wife, and two small sons (not to mention Livia) were in a besieged city and he did nothing to help them. But I tried hard to look at things from Antony’s viewpoint and also to imagine why Octavia stayed loyal to him, what she found appealing. I didn’t want him to come off as a cartoon villain.

Livia's sister Secunda, who marries a merchant rather than a politician, prefers to avoid the spotlight; she serves as Livia's foil and gives her insight into what the Roman people really think about her. Is Secunda a historical character, and if so, how much is known about her?

Roman historians recorded quite a bit about Livia’s father, but I found only scraps of information about other members of the family she grew up in. We know she did not have a biological brother because her father adopted an adult male relative with the goal of carrying on the family name. Livia may or may not have had a sister or sisters. If she did have one, that person apparently stayed completely out of view.

Roman women in Livia’s time were given the feminine form of the family name. So any sisters she had also would have been called Livia—confusing in a novel! Secunda was a nickname for a second daughter. I gave Livia a younger sister because she seemed like the big sister type to me. It’s not improbable that as a young woman she had some surviving relative around who could link her to her childhood, but we really don’t know if she did. I wanted Secunda to be a reminder of Livia’s past.

It was great to see that I Am Livia had made it as a finalist in the 2011 Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award competition. Can you talk a little bit about what this American Idol-style writing contest was like for you as an author?

The ABNA contest is great for aspiring novelists because breaking in is so challenging and this is a way to get your writing noticed. After the initial pitch stage (entries first compete on the basis of a 300-word book pitch), there are three points at which you receive reviews of your work and may or may not progress in the competition. I think most people feel a certain amount of angst anticipating the reviews. I certainly did—it was a lot like waiting for Simon Cowell’s take on my singing. But the feedback can be valuable and the contest is a learning experience. A community has developed on the contest discussion boards where contestants share information about writing and critique each other’s work. The mutual support and camaraderie are amazing.

I had a fantastic time at the award ceremony in Seattle. The highpoint for me was giving a reading from I Am Livia at the Amazon campus. Being showered with gifts—books and more books, plus a Kindle—was nice, too. The people at Amazon, both those associated with the competition and those at Amazon Publishing—my editor Terry Goodman above all—have been enormously supportive of me as an author, and I’m very grateful.

~

Phyllis T. Smith's I Am Livia will be published on May 1st by Lake Union, an imprint of Amazon Publishing ($8.97 trade paperback, $4.99 ebook, 394pp).

What draws you to ancient Rome as a setting?

I remember as a child loving Rosemary Sutcliff’s novels set in Roman Britain. Later, I enjoyed I Claudius (both the book and the TV miniseries), which introduced me to Livia as a fictional villain. In college, I took a wonderful classical civilization course that exposed me to Plutarch’s Lives. The high drama of Roman history just spoke to me. Then, too, I’m struck by how in the later years of the Republic the Romans were dealing with problems that might have some parallels today. Reading Cicero’s correspondence, I feel much closer to him than I do to medieval kings when I read primary source material about them. From his letters, he could almost be a modern politician. But of course he wasn’t that. The Romans lived in a world which was similar to ours in some ways, but also profoundly different, which is what makes them so fascinating.

I remember as a child loving Rosemary Sutcliff’s novels set in Roman Britain. Later, I enjoyed I Claudius (both the book and the TV miniseries), which introduced me to Livia as a fictional villain. In college, I took a wonderful classical civilization course that exposed me to Plutarch’s Lives. The high drama of Roman history just spoke to me. Then, too, I’m struck by how in the later years of the Republic the Romans were dealing with problems that might have some parallels today. Reading Cicero’s correspondence, I feel much closer to him than I do to medieval kings when I read primary source material about them. From his letters, he could almost be a modern politician. But of course he wasn’t that. The Romans lived in a world which was similar to ours in some ways, but also profoundly different, which is what makes them so fascinating. In your author's note, you mention that Livia is thought to be the most powerful woman in the history of ancient Rome. How much did this play into your decision to choose her as a subject?

It was a big part of my decision because I’m interested in women in politics. For most of recorded history, women have been limited to exerting influence through their relationships with powerful men. Now in many places they’re coming into their own and are increasingly holding high public office. I’m gripped by the question of what that means for the world; I certainly hope it means something good. There is evidence that Livia used her influence to make Caesar Octavianus’s rule more benign. She ultimately paid a price, in being defamed by some Roman historians who didn’t like the idea of a powerful woman.

It’s surprising how much Livia acted like a modern first lady, with her charitable activities and her going to comfort disaster victims. She had to project an image of ideal Roman domesticity, while helping to run an empire. The concern with a family-oriented image seems very modern. So in the book I was able to play with this question: What is different now and what is the same?

You present Caesar Octavianus from a viewpoint that readers don't normally see. What more did you discover about him as a character when envisioning him through Livia's eyes?

Caesar Octavianus knew how to be ruthless in public life. But there is no way to make his behavior with Livia psychologically comprehensible unless you assume he was capable of deep human emotions, including love. Looking at him through Livia’s eyes, I could see him as someone plunged as a teenager into a viper’s nest—Roman politics at that time. Not that he deserves a moral pass, but he lived in a harsh world. In the book, Livia sees all the ways in which he is vulnerable, including the fact that when he goes out to fight a battle there’s no guarantee that he’ll win or even survive.

The scene in which Tiberius Nero and his pregnant wife Livia invite Caesar to a dinner party at their home was one of my favorites, not just because it brings so many strong personalities together for a social event but also because it reveals new sides to everyone's character. Was it as enjoyable to write as it was to read?

I love hearing that you liked that scene! It was very enjoyable to write. In particular, I got a kick out of weaving in mythology. I knew that Caesar in later years tried to write a tragic play about Ajax, the warrior in the Iliad. (He decided he had no talent and threw the play away.) I wondered why he picked Ajax of all people as his tragic hero. No biography I read explained that. But in the Iliad I came across Ajax’s prayer for light on the field of battle. This fit in well with Caesar’s recorded reverence for Apollo, god of light and knowledge. In the dinner party scene, Caesar talks about Ajax, and people speak revealingly about their favorite deities. Meanwhile, the attraction between Caesar and Livia begins to sizzle, and that was fun to show.

author Phyllis T. SmithI thought you did an excellent job bringing a human dimension to many iconic figures from the period. Were any of them more of a challenge to relate to, or to re-create on the page, than others?

author Phyllis T. SmithI thought you did an excellent job bringing a human dimension to many iconic figures from the period. Were any of them more of a challenge to relate to, or to re-create on the page, than others? Mark Antony was hard to relate to. I just didn’t like him much! Not because his love affair with Cleopatra made his wife Octavia’s life unpleasant, though it certainly did. But because he was gratuitously brutal and did things like ordering Cicero’s head and hands cut off in revenge for his oratory. I found Antony’s indifference to his supporters during the Perusian War repellent, too. His brother, wife, and two small sons (not to mention Livia) were in a besieged city and he did nothing to help them. But I tried hard to look at things from Antony’s viewpoint and also to imagine why Octavia stayed loyal to him, what she found appealing. I didn’t want him to come off as a cartoon villain.

Livia's sister Secunda, who marries a merchant rather than a politician, prefers to avoid the spotlight; she serves as Livia's foil and gives her insight into what the Roman people really think about her. Is Secunda a historical character, and if so, how much is known about her?